The Last Half-Century of Psychiatric Services as Reflected in Psychiatric Services

Abstract

The last half-century of psychiatric services in the United States is examined through developments and trends reported in the 50 years of publication of Psychiatric Services. The journal, earlier named Mental Hospitals and then Hospital and Community Psychiatry, was launched by the American Psychiatric Association in January 1950 and marks its 50th anniversary this year. The author organizes his review of psychiatric services largely around the locus of care and treatment because the location of treatment—institution versus community—has been the battleground for the ideology of care and for the crystallization of policy and legal reform. He uses "dehospitalization" to describe the movement of patients out of state hospitals, rejecting the widely used term "deinstitutionalization" as inappropriate; one reason is that the term wrongly implies that many settings where patients ended up were not institutional. Also covered in detail, as reflected in the journal, are community care and treatment, economics, patient empowerment, and the interface issues of general hospitals, outpatient commitment, and psychosocial rehabilitation. The author notes that some concepts, such as outpatient commitment and patient empowerment, emerged earlier than now assumed, and that others, like psychosocial rehabilitation, recurred in slightly different forms over time. He concludes that even after 50 years of moving patients out of state hospitals and putting them somewhere else, mental health policymakers and practitioners remain too myopically focused on the locus of care and treatment instead of on the humaneness, effectiveness, and quality of care.

Anniversaries provide the backdrop for two important types of social interaction. They are the occasion, first, for collective expressions of sentiment and, second, for hard-headed retrospection and assessment. Unless we look back from time to time and appraise our course, we will repeat past mistakes or make similar ones next time around.—Eli Ginzberg (1).

The American Psychiatric Association announced in November 1949 that under a grant from the Commonwealth Fund, it was launching a Mental Hospital Service that would include a monthly mental hospital news bulletin. The publication, initially called the A.P.A. Mental Hospital Service Bulletin, was first published in January 1950. Its name changed as of the seventh issue of volume 2 to Mental Hospitals. In January 1966 it was renamed Hospital and Community Psychiatry, and in January 1995, at volume 46, its name was changed to Psychiatric Services.

The year 2000 is the 50th anniversary of the journal and an opportune time, as Ginzberg notes, to reflect on our past so that it may better inform our future. This paper uses the 50 years of this journal's publication to examine the history of the last half-century of psychiatric services in the United States. For convenience, when the journal is cited in any general way, it will be referred to as Psychiatric Services.

Background

When considering the contents of this paper, three basic issues arose. The first was how to keep the paper focused, which requires acknowledging that much in a 50-year history of psychiatric services could not be covered. The paper is largely organized around the locus of psychiatric care and treatment during the last half-century. This point of view was chosen because the location of treatment has been the battleground for the overarching ideology of care and treatment, and hence the nidus for the crystallization of policy and legal reform, for 50 years.

The debate, of course, has been about institutional care and treatment versus community care and treatment. This focus has been soundly criticized (2,3), and rightly so. It has distracted us from appropriately examining the adequacy, quality, individualization, and respectfulness of psychiatric care and treatment. Nonetheless, it is the history of psychiatric services during the second half of the 20th century.

Staying fixed on a focus that can be contained within an article means that many topics are not addressed. Because this is a paper on psychiatric services, most psychopharmacology advances are not included. Also not covered in the paper, although they have received ongoing coverage in the journal, are children and adolescents (4), the geriatric population (5), and women (6) as well as more discrete subpopulations such as mentally ill mothers (7,8), young adult chronic patients (9), persons with both mental illness and substance abuse (10), and recipients of psychiatric services who speak out about them (11).

The second issue that arose is that in discussing psychiatric services, we don't know what we're talking about. I don't mean that pejoratively, but literally. We use terms that fail a basic test of communication: that people know what you mean when you use them.

The buzzwords of the last 50 years of psychiatric services are undefined, ill defined, or differently defined by each person who uses them to meet his or her needs. Terms that fall under the penumbra of ambiguity, and have been so identified in the pages of Psychiatric Services, include these ten examples: "deinstitutionalization" (12,13), "community" (12,13,14), "chronic mental illness" (13,15), "case management" (16,17,18), "empowerment" (19,20), "recovery" (2), "service system" (21), "advocacy" (22), "patient-client-consumer" (23,24), and "least restrictive alternative" (12,25). I can hardly create a new language for this paper, so I will use the jargon we have all come to employ and do my best to make it clear.

The third issue was how to deal with "deinstitutionalization." Variously called a "policy," a "concept," a "movement," a "protest movement" (26), even an "era," deinstitutionalization is probably best labeled a "factoid." Basically, deinstitutionalization wasn't. That is, it wasn't preconceived, and it probably never happened.

The depopulation of America's state hospitals occurred because of a confluence of several factors: resource-poor state hospitals at the end of World War II; the belief that treatment closer to relatives and community jobs was better than isolated, segregated treatment; the first psychopharmacologic revolution, with chlorpromazine; empowerment of legal advocacy and an activist judiciary; and—perhaps most important—the ability of states to shift costs to the federal government through Medicaid, Medicare, Supplemental Security Income, and federal grants (27,28).

There may be no better evidence that the process of moving patients out of state hospitals started considerably before any designation of the process as "deinstitutionalization" than that between 1954 and 1976, the census of public psychiatric hospitals decreased by 70 percent (a point to be discussed later in this paper), while the term "deinstitutionalization" did not appear in the index of Hospital and Community Psychiatry until 1975. It did not appear in the title of a paper in this journal until 1976 (29).

What actually did take place was labeled by Talbott (27) at the end of the 1970s as "transinstitutionalization." He described it as "the chronic mentally ill patient had his locus of living and care transferred from a single lousy institution to multiple wretched ones." In the 1990s many state hospitals are far better than "lousy," many nonhospital living arrangements are far better than "wretched," and some of both kinds of facilities can be excellent. However, the quality of the place one resides in is distinct from who does or does not call it an "institution" and therefore has little to do with "deinstitutionalization."

Having attended to these three issues, I will look at the development of psychiatric services over the last 50 years under the headings of "dehospitalization," community care and treatment, economics, empowerment, and interface issues. As a background for what was accomplished by those directly involved in developing and implementing psychiatric services during this past half-century, it is helpful to be aware of what the federal government and the courts were doing that shaped these developments. Table 1 provides this information; the sources for it are mostly the journal's News and Notes section and the Law and Psychiatry column edited by Paul Appelbaum, M.D. In most cases it is not clear whether the government and the courts were leading or were following public or professional sentiment. However, in all cases the government's and the courts' efforts have been fundamental to the changes that ensued.

Editor's Note: As we note in several ways in this issue, 2000 marks the 50th anniversary of Psychiatric Services. In this major review, Jeffrey L. Geller, M.D., M.P.H., a member of the journal's editorial board and its book review editor, draws on material published in the journal since its founding in January 1950 to examine the last half-century of psychiatric services in the United States. The paper is dedicated to the memory of Walter E. Barton, M.D. (1906–1999), who was medical director of the American Psychiatric Association from 1963 to 1974 and who had a keen interest in the history of psychiatry.

Dehospitalization

Because the term deinstitutionalization seems to be inappropriate for the movement of persons in state hospitals out of them, the term "dehospitalization" is employed here. The term has been used in Psychiatric Services (30), although rarely. Its use predates the use of "deinstitutionalization," and it seems more accurate for describing a phenomenon of transferring patients out of state hospitals because it implies no judgment about whether where they went could be considered an institution (14).

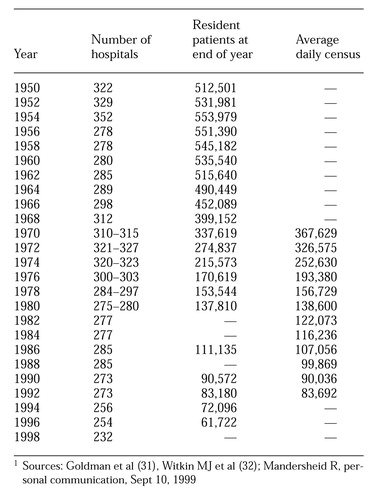

That the last 50 years was really an era of dehospitalization can be gleaned from Table 2, showing data for state and county hospitals from 1950 through 1998 (31,32; Manderscheid R, personal communication, Sept 10, 1999). As the table shows, the decrease from the highest number of hospitals, in 1954, to the lowest number, in 1998, was 34 percent, whereas the year-end census of patients between 1954 and 1996 decreased by 89 percent.

Much of this decrease in the size of state hospitals is attributable to shortening lengths of stay. For example, between 1971 and 1975, there was a 41 percent decline in length of stay (excluding deaths), or a decrease in the median length of stay from 44 days to 26 days (33). For all the attention that the closing of state hospitals has received, it has really been the movement of patients out of each of the state hospitals and each hospital's progressive decrease in size that account for the lowered national state and county hospital census.

In 1991, discussing his tenure as an attendant at Worcester (Mass.) State Hospital in the early 1950s, Vogel (34) indicated that he was personally responsible for 55 patients, the licensed nurse oversaw the care of 700 patients, and the physician was seldom seen except to certify deaths. Patients' freedom of movement was unpredictable as "patients were sometimes put into physical restraints because staff objected to their habit of masturbation, wandering, or simply getting into things." Patients were given work assignments because "the hospital virtually would have ceased to function had it not been for its unpaid workers." Vogel's comments conjure up images of what people think of as all aspects of all state hospitals of the late 1940s and 1950s—"snake pits."

Vogel's memoir is without doubt true, and it was not published until fairly recently because few publications of the earlier era were exposing the condition of state hospitals. (Exceptions were Mary Jane Ward's The Snake Pit, published in 1946, and Albert Deutsch's The Shame of the States, in 1948.) However, some rather surprisingly positive movements were also occurring. Most prominent among them is what we would now label psychosocial and vocational rehabilitation. Throughout the 1950s scores of examples of state hospital programs articulated the principles that the focus of the state hospital was to prepare patients to live in the community, that work and social skills were essential components of successful community living, and that it was the hospital's task to teach patients these skills (35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43).

Not only were social skills and vocational training recognized as important, but it was also recognized that effective interventions in these areas required a multidisciplinary effort (41,44). Further, personnel were aware of the risks of prolonged stays in state institutions, a condition called by some "institutionalitis" (45). And all these efforts were made in acknowledgment that not the hospital—but rather the community—was the focus: "As we come to accept the circumstances of hospitalization as just one aspect of treatment, and possibly not an essential phase at that, there is an increasing preoccupation with those aspects of illness as displayed in the community" (41).

During this era, overcrowding and underfunding were rampant (46,47,48), standards were low to nonexistent 46,47,49,50,51,52), and the rehabilitation effort could not be sustained. The 1960s was a decade during which the leaders of state hospitals were busy redefining the role and designing the functioning of state hospitals to ensure the hospitals' future existence (53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62). Other issues that were being considered during this era were state hospital habituation ("institutionalism") (63,64), the sufficiency of no more than symptomatic relief (65), families' and patients' resistance to discharge (66,67), and the development of adequate community programs to effectively maintain individuals with chronic mental illness outside state hospitals (68,69,70,71).

The 1970s can be best characterized by a mid-century statement that "hospital-busters and hospital-preservers agree on only one point—there is no single universally applicable solution to the problem" (72). It was in this period that the real debate about closing or retaining state hospitals emerged (73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81), and some state hospitals were actually closed (82,83,84). While the political debate raged, state hospitals began to become more integrated into community services, largely through unitization—that is, geographic matching of state hospital wards and catchment areas (85,86,87).

As components of this transition, prospective patients began to be denied admission with a new vigor (88,89), outcome data began to be examined (90,91,92,93), and even purchase of service contracts with state hospitals was proposed (94). Perhaps the best summary statement about state hospitals during the 1970s is that of Maxwell Jones (95): "I'm very worried about state hospitals, which I visit in many parts of the country. They are all demoralized and feel forgotten. The interest (and money) has moved to the new community programs, which are not supplying the answer to chronic mental patients."

Of the last five decades, the decade of the 1980s was the least innovative as far as state hospitals were concerned. The issues of the 1970s continued to be prominent: the role of the state hospital (21,96,97,98,99,100,101), including whether more state hospitals should be closed (102) or if in fact any were necessary (103); efforts to reduce state hospital admissions (104,105,106,107,108,109); and further refinements of state hospital organization and management (110). Perhaps the one new debate—or at least it was formulated more explicitly—was the controversy on the pros and cons of "deinstitutionalization" (111,112,113,114).

Issues surrounding psychiatric services in state hospitals in the 1990s were basically more sophisticated examinations of the issues developed in the 1970s and somewhat refined in the 1980s. The psychiatric profession was focused on how the population that uses state hospitals was changing (115,116,117,118,119); who kept returning despite the improvement of community services—that is, the examination of "recidivism" (120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128); and the need for asylum for certain patients (129,130). A continuing argument was that on the one hand we had more patients in state hospitals than needed to be there (131,132), and on the other that many with chronic mental illnesses needed long-term inpatient treatment (133,134,135).

Strong criticisms of the role of the state hospital also erupted in the 1990s. The 30-year debate on this role has been driven more by ideology than by patient care needs (136,137). Shame on us all.

Community care and treatment

In the early 1950s, Daniel Blain (138), then the medical director of APA, was already explaining the change in emphasis from hospital to community-based care: "The emphasis upon out-patient services, home treatment, day hospitals, and the like grows out of the recent advances in psychiatry which have made possible much care and treatment without hospitalization." The foundations for many of the "innovations" of the 1960s through the 1990s were actually rooted in the 1950s. The programs were not widespread in the 1950s, but they were emerging, and they were felt worthy of discussion in the literature.

As the state hospitals in the 1950s were preparing to discharge patients who did not need hospital-level care, what were community-based professionals doing? Interventions that began to blossom in the 1950s included general hospital psychiatric units (139,140); outpatient clinics (140,141); halfway houses (142,143,144); day hospitals (140,145); social clubs for "ex-patients" (138,146); family care (146); antistigma interventions (141,144,146); preventive services (138); and the use of visiting professional teams to go into patients' homes (138), private doctors' offices, (147) or remote rural areas (148).

While model service delivery methods were being developed, earlier treatment methods such as hydrotherapy (139), and earlier problems such as staff shortages—for example, two social workers for 3,200 patients (142)—simply moved into the new loci of care and treatment.

The 1960s might well be characterized by an axiom recounted in 1960: "The patient is better off in the community, and the hospital is better off without the patient" (149). By the early 1960s principles of community treatment were well articulated (150). First, whenever possible, a patient should remain in his or her home community and be treated there. Second, hospitalization, if required, should be short, with a rapid return to outpatient services. Third, early intervention should be available to avoid the need for hospitalization whenever possible. And finally, programs offering alternatives to hospitalization should be fostered, as they will be less expensive and more therapeutic.

By the mid-1960s the mental health professions had a good understanding of what comprehensive treatment in the community meant: "Comprehensive community psychiatry refers to an array of therapeutic and supportive programs designed to meet the needs of all patients and to meet the needs of a single patient at different times during the course of his illness" (151). At the same time came the early recognition that the public and private sectors were beginning to blur: "The rise of community psychiatry is creating a closer relationship between public and private agencies and institutions and, to some extent, is diminishing their functional differences" (152).

The 1960s saw refinements of many of the interventions of the 1950s, such as general hospital psychiatric units (153), day hospitals (154,155,156), night hospitals (154,155), halfway houses (157,158), social rehabilitation and employment (159,160,161,162), and outpatient clinics (163,164,165). New interests in the 1960s, or those that began to receive more attention, included emergency services programs (150,166), services to police departments (167,168) and correctional facilities (167), hospital readmissions (163), adequate housing (159), the employment of former patients in human services (169), and the integration of services across organizations (170,171).

Two interesting points of debate that would hound mental health professionals throughout the remainder of the century were clearly set out in this era. The first focused on the issue of the permanence of community-based services and the accompanying demise of state hospitals. Thus Greco (166) wrote in 1961, "Any reversal of the present-day trend toward keeping patients out of the hospital as long as possible, and discharging those admitted at an early date, seems unlikely," while Ewalt (167) said in a keynote address that same year, "The state hospital has been investigated, inspected, reorganized, converted, divided, dispersed, and even abolished, in fact or in theory, by countless imaginative persons motivated by a variety of urges. The state hospital survives, however, and is an amazingly tough and resilient social institution."

The second long-lasting issue was the dynamic tension between autonomy and dependency in relationship to services provided to those with chronic mental illness. Drubin (154) wrote in 1960: "Again we cannot help but ponder whether or not we might be developing a tendency to provide too many crutches or even stumbling blocks rather than stepping stones to final discharge from the hospital by referring more patients than necessary to the day-hospital, night-hospital, foster home, cottage plan, half-way house, member-employment program, or patients' discharge quarters."

An early statement of the 1970s was Hirschowitz' view (172) that "many programs have demonstrated that biopsychosocial principles can be practiced and applied to the management and rehabilitation of psychiatric casualties." Two other propositions that would become foci of discussion for the next 30 years were set forth by Feldman (173) early in the 1970s. First was the dilemma of a two-class system of care: "As we have learned to our great misfortune in this country, services offered only to the poor quickly become poor services." The other was the matter of the involvement of recipients of services in the development of those services: "Responsiveness simply means that people who receive mental health services must have something to say about the nature of those services and the way in which they are provided. We are clearly in an age of consumer rebellion, and mental health services should be no less a target than automobiles, industrial pollution, or phosphate detergents" (173).

The 1970s witnessed further development, and new evaluation, of service interventions established in the preceding two decades. Among them were residential facilities (174,175,176,177,178,179), employment programs (180,181), traveling teams of professionals (173,182), and programs to address readmissions (183,184,185,186). New concerns were expressed about hospital admission rates (181,187,188), and programs were developed to provide acute psychiatric treatment in nonhospital settings (181,189). Evaluation studies of services began to be undertaken (190,191,192), and an early attempt at utilization review was made (193). Two issues that would haunt the provision of psychiatric services to the end of the century emerged in this decade: the application of the principle of the least restrictive alternative in psychiatric services (181) and the burden of restrictive formularies (182).

Two new forms of services were born during the 1970s. One became known as case management. In the 1970s there were two descriptions of providers that would certainly be called case managers today; they were known as "brokers" in one service system (194) and "continuity agents" in another (195).

The second new kind of service was what is now called assertive community treatment. Drawing on principles intermittently articulated throughout the previous 20 years, Stein and Test created a program to help individuals with chronic mental illness sustain community life that would be as free of inpatient treatment as possible, prevent the development of the chronic patient role, maximize community adjustment, improve self-esteem, and enhance quality of life (196,197). Test and Stein (198) articulated two guiding principles that could be the clarion call for the rest of the century for the nature of psychiatric services for those with chronic mental illness: "A special support system should be adequate to assure that the person's unmet needs are met" and "A special support system should not meet needs the person is able to meet himself."

The 1970s were characterized by surprises about and criticism of the ideology of the transfer of care that was driving clinical services. In one catchment area of San Antonio (Tex.) State Hospital, the establishment of a community mental health center actually increased rather than decreased state hospital admissions (188). Maxwell Jones (192) was highly critical. He indicated, "I am unaware of any state that was circumspect enough to request adequate information before supporting this movement of chronic mental patients from the state hospital to the community. The political and economic pressure to lessen the tax burden by lowering the hospital census has been too strong." Further, he remarked, "It seems to me that the tendency to use nursing and boarding homes cannot be equated with health planning, but rather lack of it."

One of the last comments of the 1970s about community care, published in the December 1979 issue, provided one administrator's startling epiphany: "Patients often do not see life in the community as more desirable than life in the institution; if they did, they would leave the institution" (199). Really?

The message of the 1980s was that community services needed to be significantly improved to meet the needs of those who were in the community as the result of dehospitalization. "Planners, leaders in psychiatry, and government officials simply cannot be allowed to proceed with deinstitutionalization in the absence of adequate community programs—at the very time when new, young chronic patients are emerging in unprecedented numbers," said Talbott (200).

Better-planned and further-developed services were promoted or initiated in the areas of needs assessment (201,202); aftercare specialty services (203,204,205,206,207); case management (16,18,208,209); residential care, including quarterway houses (210,211,212), three-quarter-way houses (213), board-and-care homes (214), and boarding homes (215); community mental health centers (216,217); continuity of care (218,219); asylum care (220) and autonomy (221); family care (222); and crisis care (223,224). There was a renewed focus on evaluation research, including prediction, outcome, and effectiveness studies, on such topics as adjustment to community living (225), hospital admission rates (226,227), effects of case management (228,229), quality of life (230), treatment compliance (231), and intensive residential treatment (232).

A population that emerged as of particular interest, and one that would remain of significant concern during the next two decades, was the homeless mentally ill. The situation was described in 1983 as follows: "The homeless have become a major urban crisis. The streets, the train and bus stations, and the shelters of the city have become the state hospital of yesterday" (233).

In community care, the 1980s was a decade of consolidating practices, evaluating efforts, and facing new problems. It was more of a decade of tinkering than it was of innovating.

The 1990s might best be characterized by an insight in a Taking Issue column by Lamb (234): "Ideology should not determine clinical practice, but rather clinical experience should determine ideology." An example of ideology determining practice was revealed in Geller's evaluation (235) of a crisis service's mission to divert admissions from the state hospital with the expectation (or even "knowledge") that it would produce treatment closer to individuals' homes and in the "least restrictive setting." The outcome did not support the ideology; patients were often hospitalized at a location across the state to avoid admitting them to the state hospital, which was much closer to their neighborhood.

The last decade of the century included extensive evaluation of what psychiatric services had and had not accomplished under the umbrella of community services. Services scrutinized included case management (236,237,238,239,240), residential programs (241,242,243,244,245,246), partial hospitalization programs (247,248,249), admission diversion interventions (235,250), and attempts to address noncompliance (251,252).

One service type of particular interest was continuous treatment teams, most commonly labeled assertive community treatment, or ACT (253,254,255,256,257,258,259). Although assertive community treatment was reported in many demonstration projects as a successful intervention on many outcome variables, an unsettled debate remains about ACT's place in the overall service system. McGrew and colleagues (258) decided it was time for "wide-scale dissemination of assertive community treatment as an effective form of community care for persons with serious mental illness." Burns and Santos (256), in a review article, concluded that studies to date did not answer the question "of the place of assertive community treatment in a system of care."

Two populations of particular interest during the decade of the 1990s were the homeless mentally ill (260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267) and hospital repeat users or recidivists (238,268,269,270). One of the more poignant articles about homelessness, one that helps in distinguishing between ideology and reality, was the description of shelter life by Grunberg and Eagle (260). How different is the Fort Washington Men's Shelter in New York City, as they portray it, from state hospitals at their worst in the "predeinstitutionalization era"? "The residents sleep in cots on the armory drill floor. No walls separate them from each other or from the public view…. The windows are poorly lit, and walls are streaked with dirt. Various corners are damp with urine…. Doors are missing from bathrooms…. The beds are lined up in rows of approximately 20 beds wide and 50 beds long, with usually only one or two feet between them…. Approximately one-fourth of the residents choose to spend their day inside the shelter and may not leave the building for days or weeks at a time."

In order to move us away from ideologically determined to clinically rooted policy, principles of care and treatment were promulgated, including those by Bachrach (271) and Munetz and colleagues (272). The basic components of these principles were that mental illness is a biologic disorder, with its expression influenced by genetic, personal, and environmental factors; the person is not the illness, and the illness is not the person; services must follow assessment, must be individualized, and must be modified as needed; treatment must be as aggressive as warranted, while respecting whatever degree of autonomy the recipient of services is capable of; treatment needs to be culturally informed and involve family members and significant others; recipients of services need to be involved in the planning of those services to whatever degree they are capable of; and outcomes of services must be realistic, researchable, and researched.

Where are we now? One conclusion is that in someplace approaching nirvana, the state hospital can be completely replaced by a community-based system of care and treatment. Thus Okin (273) concluded about western Massachusetts, "With a clear vision, concerted political will, a supportive constituency, a powerful catalyst (in this case, a judicially enforced consent decree), sufficient resources, and careful targeting of these resources to specific services designed to serve patients with severe and persistent mental illness, it is possible to develop a system of care in the community that can substantially and responsibly reduce, or totally eliminate, the need for state hospital treatment."

Even if this is so, are persons with chronic mental illness then "deinstitutionalized"? Robey (245) found that, to some extent, supervised living arrangements typically provided by community residential and transitional housing agencies are likely to represent for the residents an institutional or semi-institutional environment. And Lamb (274) reported on a "95-bed locked community facility," one of 40 such facilities in California. By what stretch of the imagination are secure facilities of 100 (more or less) inhabitants, also known as patients or inmates, providing "life in the community"?

All too often, psychiatric services continue to be built on wishes for outcomes rather than on data (250). And we remain trapped between the dialectic of the legalistic goal of minimizing restrictions on liberty and the clinical goal of maximizing clinical outcomes through optimal treatment interventions (272).

Economics

In every decade of the last five, questions about who would pay for care and treatment were raised. In no decade did there appear to be any widespread endorsement of a major intervention that will cost more and be the right thing to do. Rather, new, more humane, or more respectful interventions have been consistently tied to cost savings.

In the 1950s life at the state hospital was surrounded by cost issues, such as savings earned through new equipment (275,276) or whether to have a state hospital farm (277,278,279). In an era when the average state hospital was operating at a cost of $2.70 per capita per day (280), the introduction of chlorpromazine proved to be a budget buster—pharmacy costs increased 20-fold (281). That community treatment could be less costly than hospital treatment was recognized in the 1950s (282).

Mental health care in the 1960s benefited from several policy changes at the federal level. Buildings were in use that had been built with expanded Hill-Burton funds under the Hospital Survey and Construction Act (P.L. 79-725) (283,284). Federal welfare payments were extended to conditionally discharged psychiatric patients (285), and Congress passed the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Centers Construction Act of 1963 (P.L. 88-164) (286). Professionals began to push for better health insurance, including coverage for partial hospitalization (287). The argument for insured partial hospital treatment was further pursued in the 1970s (288).

By 1970 it was clear that the absence of federal money for staffing community mental health centers (CMHCs) meant that 60 of those planned would not open or would provide "weak and ineffective programs" (289). It was also clear that for acute illnesses, short-term hospitalization—two to four days—and immediate return to the community "will not only be expected, but also required" (290). Further, articles with early data were indicating that individuals who had chronic mental disorders could be cared for less expensively in the community than in the hospital (291,292,293,294).

By the early 1970s it was starkly apparent that a national plan was needed to simultaneously address financing, comprehensive coverage, and the restructuring of the delivery system. This realization led to the Health Security Program, promoted by the Committee for National Health Insurance (290,295,296). President Nixon also submitted a bill for national health insurance (297). President Carter, in 1977, indicated that national health insurance was high on his agenda (298).

A class-action suit that profoundly affected the future of the state hospitals was aimed at requiring the Labor Department to enforce at state hospitals the minimum wage and overtime provisions of the 1966 amendment to the Fair Labor Standards Act (299). The decision in Souder v. Brennan put a stop to most work done by hospitalized patients (300), ending both patient exploitation and useful work by inpatients.

The 1980s saw considerable legislative activity that could affect mental health care and treatment. On the federal level it included equal coverage for mental illness in federal employees' insurance (301), Social Security Disability Insurance (302,303,304), and prospective payment (305,306). On the state level there was a focus on minimum inpatient and outpatient benefits (307). Other economic issues active in the 1980s were the risks of the bottom line overriding patient care needs in for-profit hospitals (308), the relationship of payment method and hospital use (206,309,310,311,312,313), and the relationship between patient characteristics and the cost of inpatient treatment (314).

In the 1990s much attention was paid to federal programs or lack of them, including Medicaid (315,316), Social Security Disability Insurance (317,318), equitable mental health coverage (319,320,321), cost shifting (322), and national health insurance (323). However, the major economic focus of the 1990s was managed care, private and public.

Before 1990 most of the focus on managed care had been on health maintenance organizations (HMOs) (324,325,326,327,328,329,330,331). In 1990 Dorwart (332) discussed myths about managed mental health care, including that managed care caused, and that managed care would cure, the current problems of mental health care. Throughout the 1990s managed mental health care rolled itself out, first on the private side and then on the public (333,334,335,336,337,338,339,340,341,342,343,344,345,346,347,348,349,350).

Although this paper cannot do justice to the phenomenon of, issues with, or strengths and liabilities of managed mental health care, it is worth noting that little in private managed behavioral health care, and even less in public managed behavioral health care, is new. Most inventions, attempts at cost savings, and use of alternatives to inpatient care were developed in the public sector long before managed care (351,352). People in states that implemented public-sector managed care and the development of community services simultaneously see them as causally linked; those in states that implemented these two service delivery changes consecutively know otherwise.

Empowerment

Neither empowerment of patients nor empowerment of families is of recent origin. The first issue of the first volume of Psychiatric Services included an item on a "club" formed by patients, ex-patients, and family members (353) and one on a relatives' organization known as the Friends of the Mentally Ill (354). Part of the latter group's mission was to seek legislation for better psychiatric facilities and improved treatment.

In the 1950s consideration was given to increasing patients' freedom in the hospital (355) and to employing patients in the hospital (356). The importance of patients' engagement in productive work was discussed above. This movement continued in the 1960s with patients' putting out a newsletter (357); being prepared for competitive employment (358,359); working as therapy aides (360,361); and helping as hospital volunteers (362) or as hospital workers (363,364). While the state hospital often needed patients to work due to staff shortages, the work programs were seen as vehicles of empowerment and skills training that would better equip patients for life after hospital discharge.

The 1970s continued the efforts seen in the two preceding decades. Patients were helped to obtain jobs (365), including performing staff members' functions (366,367). Emphasis was placed on "normal work environments" (368). However, a damper was put on most hospital-based work programs with the ruling in Souder v. Brennan that patients must be paid the minimum wage (300). An addition to patient empowerment in the 1970s was the introduction of the patient advocate (22,369,370). The advocate's role was not without considerable controversy at the time (22), and it has remained so.

One term is worth highlighting. Labeling patients or ex-patients "consumers" is not a function of the patient empowerment movements of later years. Rather, the term "consumer" was applied to patients and former patients by psychiatrists of the 1970s (371).

Two major undertakings of the 1980s were to have profound effects on empowerment for the remainder of the century. The first was the incorporation of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) in 1980 (372). By the mid-1980s interventions and formal expressions of opinions by NAMI affiliates were affecting mental health policy (373,374). The second was the use of self-help groups by those with serious mental illness (375,376,377,378). As expressed by Estroff (375) early in the decade, self-help groups were to be "a genuine, not an artificial, partnership in order to solve complex and painful problems." Estroff made a prescient observation—namely, that self-help groups would be more of a challenge for staff than for patients. As for terminology, in another commentary, for the first time an author identified herself in the journal as a "former psychiatric inmate" (377).

The 1990s were highlighted by persons with mental illness promulgating their own philosophies and definitions of empowerment. Fisher (379) indicated that the major actions needed to facilitate recovery from disabilities were a change in "the attitudinal and physical environment rather than within the individual, an emphasis on choice in and control of services by the people who are receiving them, and an assertion that it is possible to be a whole, self-determining person and still have a disability." Rogers and others (19) developed a scale to measure the construct of empowerment, consisting of the three dimensions of self-esteem-self-efficacy, actual power, and righteous anger and community activism.

Further advances were made in areas of empowerment that began in earlier decades, including the employment of persons with serious mental illness as peer interviewers (380), peer counselors (381), and case managers (382,383,384). The self-help movement broadened (379,385), as did activities for patient advocacy and patients' rights (386).

Of particular interest is the question of how states' endorsement of patient empowerment translated into actual practice. Geller and associates (20) found that states' employment of persons with serious mental illness and their family members in state and county offices was inconsistent across the states, and considerably less than it might be. Noble (387) determined that only 16 state mental health agencies required the inclusion of a vocational rehabilitation component in an individual's treatment or service plan. It would appear that the states' endorsing the empowerment ideology has been much easier than putting anything substantial into practice.

Two related concepts that came into their own in the 1990s were "consumer satisfaction" and quality of life. Although consumer satisfaction was intermittently considered before the 1990s (388), it had become a focal point, and often a quality indicator, by the century's end (389,390). Satisfaction was examined in relation to case management services (391,392) and residential options (393,394). Studies of satisfaction began to delineate clear distinctions between patients', families', and providers' perceptions of maximal outcomes (394).

In the 1990s researchers attempted to determine what factors might affect patients' perceptions of their quality of life. One study found that quality of life could be improved by such clinical interventions as family psychoeducation; improved detection, evaluation, and treatment of depression; and more attention to side effects (395). The effects on quality of life of clubhouses (396) and of case management (397) were studied.

And finally, the perception of quality of life by a cohort of 30 patients living in community settings was examined in relation to their perception of quality of life in the state hospital they had been discharged from 11 years earlier (398). The findings indicated that individuals with chronic, serious mental illnesses, even those with multiple hospitalizations, preferred life in well-staffed community programs to life in the hospital, but that their self-esteem and overall positive feelings had not improved with the transfer to community living.

Many outcomes in this area of research were not necessarily what would have been expected. For example, satisfaction did not improve with decreasing symptoms (393), alcohol abuse had no independent association with quality of life (395), and intensive case management did not improve patients' perception of quality of life when compared with standard aftercare services (397). In order to determine how to improve quality of life, considerably more research is needed to ascertain what professionals contribute to the lives of those with chronic, serious mental illness, beyond providing adequate shelter and meals; what persons with chronic, serious mental illness contribute to their own well-being; and how each group does what it does, separately and together.

Interface issues

In this section some components of the service system that exist at the interface between the traditional sites of inpatient care—that is, state hospitals and the community—are briefly examined. They are general hospitals, involuntary outpatient treatment, and psychosocial rehabilitation.

General hospitals

In the 18th century Benjamin Rush took care of psychiatric patients in Pennsylvania Hospital, a general hospital. Philadelphia General Hospital treated psychiatric patients from its inception in 1834 (399). Massachusetts General Hospital developed a psychiatric unit in 1934 (400).

But it was not until after World War II that the treatment of psychiatric patients in general hospitals flourished. By 1963 a total of 1,005 general hospitals were treating psychiatric patients; they admitted one and a half times as many patients as the state and country psychiatric hospitals (401). By 1978 a total of 2,244 general hospitals were treating psychiatric patients; 1,100 of them had separate psychiatric units (399). By 1983 the U.S. had 1,259 general hospitals with inpatient psychiatric units; these units now provided nearly twice as many patient care episodes as the state and county hospitals, although the latter still had almost three times as many beds (402).

The expansion of the general hospital's role in providing psychiatric services has not been without controversy. By 1979 cooperative ventures existed between general hospitals and state departments of mental health (403). However, Flamm (404) admonished in that year that "it becomes very important for those of us working in general hospitals to be on guard against some growing efforts to convert general-hospital units into miniature state hospitals."

In the 1980s the major debates were focused on whether general hospitals should admit involuntary patients (405,406,407) and what the effects of dehospitalization were on general hospitals (408,409,410). By the 1990s the general hospital was well ensconced in the system of care for those with chronic mental illness (411,412), and inquiry now focused on what determined where a patient would be directed for care and treatment (413).

Outpatient commitment

Although involuntary treatment in the community, most often called "outpatient commitment," seems like a modern service intervention, it too stems from nascent efforts 30 or more years ago. In 1966, at the Texas Research Institute of Mental Sciences, a group of patients were legally committed to the institute and then immediately furloughed to the outpatient occupational therapy section (414). If a patient did not comply with treatment, he or she would be "picked up by the legal authorities and admitted to the hospital." The authors concluded that this type of intervention could decrease inpatient utilization.

Interest in outpatient commitment picked up in the mid-1980s. A national survey demonstrated that so much confusion existed about outpatient commitment that in 25 percent of responding states, the state mental health director and the attorney general could not even agree whether the state had a statute for outpatient commitment (415). A follow-up survey in 1991 showed that although states were clearer about outpatient commitment, use of this intervention was still poor (416). Reports were published on the use of outpatient commitment in North Carolina (417,418,419), the District of Columbia (420), Arizona (421), California (422), and Ohio (423).

Involuntary outpatient treatment drew progressively more attention to the point that clinical guidelines for its use were developed (424), the legal bases for its use were articulated (425), and calls for data to inform its practice were issued (426,427,428). By century's end, we were still in the position of needing better outcome studies to clarify the place, if any, of involuntary community treatment in the therapeutic armamentarium.

Psychosocial rehabilitation

As indicated in this paper's section on dehospitalization, what we would now call psychosocial rehabilitation was an active enterprise at state hospitals in the 1950s, and it was seen even then as a bridge to community life for persons with serious mental illness. A focus on rehabilitation, which was blurred in the 1960s and 1970s, reemerged with clarity in the 1980s. Unfortunately, it would appear that few remembered the work of 25 years earlier.

In the 1980s the value of work and the maximization of vocational potentials were advocated (429,430). Intervention strategies, such as psychoeducation (431), social skills training (432), and teaching of workplace skills (433), were explained; the effects of rehabilitation on recidivism were demonstrated (434,435); and outcome studies began to appear (436).

In the 1990s interventions became more sophisticated. Efforts were made to determine rehabilitation readiness (437). Work capacity of persons with schizophrenia was assessed and was determined to be at least equal in several areas to that of several other groups with different forms of disabilities (438). "Supported employment" became the concept of the moment, with variations on a basic theme of helping persons with serious mental illness who were on the job in competitive employment by such methods as assistance from agency staff, natural coworkers, personal network supports, self-management supports, a "place-then-train" approach, a "choose-get-keep" model, and the integration of vocational and clinical approaches (439,440). Ironically, the 1990s saw the full return to the 1950s in the development of psychosocial rehabilitation as one major focus of the state hospitals' tasks (441,442).

In the late 1990s in this journal, Barton (443) made an excellent recommendation for the 21st century: "Continued research is required to further specify the effects of psychosocial interventions and to determine the most effective amount and intensity of those interventions."

Summary and conclusions

In 1978 Budson and Jolley referred to the location of care for those with serious and chronic mental illness as the "location of vegetation" (436). Perhaps the most telling indictment of the system of mental health care and treatment at the end of the 20th century was that the contemporary location of vegetation was jail (444,445,446,447,448,449,450,451). Despite recent clinical interventions to keep those with serious mental illness out of jail (450,452,453,454,455,456), we remained far from achieving the wish of Eleanor Owen, cofounder of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, expressed in 1981, that "no mentally ill misdemeanant should ever be put in jail" (445).

Despite 50 years of moving patients out of state hospitals and putting them someplace else, mental health policy makers and practitioners remain all too myopically focused on the locus of care and treatment. We have yet to heed the advice that Bachrach (26) expressed 22 years ago: "The emphasis must be moved away from programs and places toward the patients themselves." We remain entrenched in our concerns about locus of care, confusing it with the humaneness, effectiveness, and quality of care.

How far have we come over the last half-century? Table 3 is included to allow readers to judge for themselves. It provides one quotation about psychiatric services from each year of publication of Psychiatric Services (taken from references 457–481 besides many already cited). Are our insights, intentions, and clarity of thinking any better directed at the end of the century than at mid-century? Are our interventions more thoughtful, sensitive, caring, and respectful? In reading the quotes, can we even tell where they come from over a 50-year span of psychiatric services?

This review of a half-century of psychiatric services is humbling. It resonates with Rosenblatt's observation (482) that "our predecessors who cared for psychotic patients were not quaint. Neither are we excessively wise."

One of the authors published in the pages of this journal wrote, "It has often been said that more has been accomplished in the field of mental health in the past ten years than in the preceding half century" (159). That comment appeared in 1960.

Dr. Geller is professor of psychiatry and director of public-sector psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School and its Center for Mental Health Services Research. His address is Department of Psychiatry, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 55 Lake Avenue North, Worcester, Massachusetts 01655 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. The federal government's and the court's provisions of the foundations for psychiatric services, 1949 through 1999

|

Table 2. Number of state and county hospitals and their census, 1950 to 19981

|

Table 3. Quotes on a half-century of psychiatric services: been there, heard that before

1. Ginzberg E: Psychiatry before the year 2000: the long view. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:725-728, 1987 Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Lamb HR: Deinstitutionalization at the crossroads. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:941-945, 1988 Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Stein LI: "It's the focus, not the locus." Hocus-pocus! Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1029, 1988 Medline, Google Scholar

4. Hartmann L: Children are left out. Psychiatric Services 48:953-954, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

5. Jeste DV, Munoz RA: Introduction [to a special section on mental health and aging]: preparing for the future. Psychiatric Services 50:1157, 1999 Link, Google Scholar

6. Ritsher JE, Coursey RD, Farrell EW: A survey on issues in the lives of women with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:1273-1282, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

7. Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL: Mothers with mental illness: I. the competing demands of parenting and living with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:635-642, 1998 Link, Google Scholar

8. Nicholson J, Sweeney EM, Geller JL: Mothers with mental illness: II. family relationships and the context of parenting. Psychiatric Services 49:643-649, 1998 Link, Google Scholar

9. Pepper B, Kirshner MC, Ryglewicz H: The young adult chronic patient: overview of a population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:463-469, 1981 Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Lehman AF, Myers CP, Dixon LB, et al: Defining subgroups of dual diagnosis patients for service planning. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:556-561, 1994 Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Geller JL, Harris M: On the usefulness of first-person accounts. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:7-8, 1994 Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Bachrach LL: Is the least restrictive environment always the best? Sociological and semantic implications. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:97-103, 1980 Abstract, Google Scholar

13. Ransohoff P, Zachary RA, Gaynor J, et al: Measuring restrictiveness of psychiatric care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:361-366, 1982 Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Geller JL: Defining the meaning of "in the community." Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1197, 1991 Medline, Google Scholar

15. Bachrach LL: Defining chronic mental illness: a concept paper. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:383-388, 1988 Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Schwartz SR, Goldman HH, Churgin S: Case management for the chronic mentally ill: models and dimensions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:1006-1009, 1982 Abstract, Google Scholar

17. Bachrach LL: Case management: toward a shared definition. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:883-884, 1989 Abstract, Google Scholar

18. Kanter J: Clinical case management: definition, principles, components. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:361-368, 1989 Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, et al: A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48:1042-1047, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

20. Geller JL, Brown JM, Fisher WH, et al: A national survey of "consumer empowerment" at the state level. Psychiatric Services 49:498-503, 1998 Link, Google Scholar

21. Bachrach LL: The future of the state mental hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:467-474, 1986 Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Stone AA: The myth of advocacy. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:819-822, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Shore MF: Patient or client? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1247, 1988 Google Scholar

24. Mueser KT, Glynn SM, Corrigan PW, et al: A summary of preferred terms for users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 47:760-761, 1996 Link, Google Scholar

25. Munetz MR, Geller JL: The least restrictive alternative in the postinstitution era. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:967-973, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Bachrach LL: A conceptual approach to deinstitutionalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 29:573-578, 1978 Abstract, Google Scholar

27. Talbott JA: Deinstitutionalization: avoiding the disasters of the past. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:621-624, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Scherl DJ, Macht LB: Deinstitutionalization in the absence of consensus. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:599-604, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

29. Doll W: Family coping with the mentally ill: an unanticipated problem of deinstitutionalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 27:183-185, 1976 Abstract, Google Scholar

30. Jarrahizadeh A, High CS: Returning long-term patients to the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 22:63-65, 1971 Link, Google Scholar

31. Goldman HH, Adams NH, Taube CA: Deinstitutionalization: the data demythologized. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:129-134, 1983 Abstract, Google Scholar

32. Witkin MJ, Atay J, Manderscheid RW: Trends in state and county mental hospitals in the US from 1970 to 1992. Psychiatric Services 47:1079-1081, 1996 Link, Google Scholar

33. Klerman GL: National trends in hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:110-113, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

34. Vogel W: A personal memoir of the state hospitals of the 1950s. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:593-597, 1991 Abstract, Google Scholar

35. Working plan for occupational therapy. APA Mental Health Service Bulletin 2(4):2, 1951 Google Scholar

36. Job placement for ex-patients accomplished by "salesmanship." Mental Hospitals 2(10):4, 1951 Google Scholar

37. Ridgway EP: Who is responsible for patient activities? Mental Hospitals 3(10):4-5, 1952 Google Scholar

38. Employment plan for patients leads to later job placement. Mental Hospitals 4(7):7, 1953 Google Scholar

39. Barry P: Purposeful work aids mental patients. Mental Hospitals 6(3):6, 1955 Google Scholar

40. Peffer PA: Rehabilitation for the mentally ill: the administration, staffing pattern, management, and control of rehabilitation, re-education, and job placement services. Mental Hospitals 7(3):11-15, 1956 Google Scholar

41. Tyhurst JS: Rehabilitation services in the community. Mental Hospitals 9(5):42-44, 1958 Google Scholar

42. Osmond H: Rehabilitation services within the hospital. Mental Hospitals 9(5):45-47, 1958 Google Scholar

43. Martin HR: Vocational rehabilitation in the mental hospital. Mental Hospitals 10(2):27-29, 1959 Google Scholar

44. Ozarin LD: Can we define disciplinary roles? Mental Hospitals 3(7):5,10, 1952 Google Scholar

45. Cole LL: "Institutionalitis." Mental Hospitals 6(2):16-17, 1955 Google Scholar

46. New York State Commission's recommendations emphasize need for more mental hospital beds, sound mental hygiene clinic programs, raised professional salaries, more research and training. APA Mental Hospital Service Bulletin 1(4):4-5, 1950 Google Scholar

47. Virginia's "Duke Report" sets pattern for constructive study of state institutions; credits present operation but recommends mental health program get priority on funds. APA Mental Hospital Service Bulletin 1(6):4-5, 1950 Google Scholar

48. Have you heard? Mental Hospitals 10(7):61-62, 1959 Google Scholar

49. Duval AM: The formulation of mental hospital standards. APA Mental Hospital Service Bulletin 2(3):3, 1951 Google Scholar

50. Texas hospital board establishes 14-point improvement program. Mental Hospitals 3(3):1, 8, 1952 Google Scholar

51. Haun P: Special characteristics of the modern mental hospital. Mental Hospitals 3(5):1,8, 1952 Google Scholar

52. Solomon HC: Hospital psychiatry today. Mental Hospitals 11(7):14, 1960 Google Scholar

53. King PD: The changing function of the mental hospital. Mental Hospitals 10(10):16-17, 1959 Google Scholar

54. Barton WE: "They also serve…" Mental Hospitals 11(6):15, 1960 Google Scholar

55. Jackson GW, Smith FV: The Kansas Plan. Mental Hospitals 12(1):5-8, 1961 Google Scholar

56. O'Neill FJ: Specialty programs in mental hospitals. Mental Hospitals 15:117-119, 1964 Medline, Google Scholar

57. Glass AJ: The future of large public mental hospitals. Mental Hospitals 16:9-22, 1965 Medline, Google Scholar

58. Blain D: The novalescent hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:1-9, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

59. Davidson HA: The folklore of "inadequate treatment." Hospital and Community Psychiatry 18(6):16-17, 1967 Google Scholar

60. Guiss RL: A project to relieve overcrowding. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 19:18-20, 1968 Link, Google Scholar

61. Moore DF: The future of the mental hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 19(2):7-9, 1968 Google Scholar

62. Schulberg HC, Baker F: The changing mental hospital: a progress report. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 20:159-165, 1969 Link, Google Scholar

63. Levy L, Blachly R: Counteracting hospital habituation. Mental Hospitals 16:114-116, 1965 Medline, Google Scholar

64. Ishiyama T, Grover WL: Flow: an antidote for stagnation. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 18:71-73, 1967 Link, Google Scholar

65. Bonstedt J, Akdogu UF: Is symptomatic relief enough? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:16-17, 1966 Google Scholar

66. Boquet RF, Henderson W: Overcoming the family's resistance to discharge. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:215-217, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

67. Hagopian PB, Collins K: Handling objections to placement plans. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 19:318-319, 1968 Link, Google Scholar

68. Barton WE: Trends in community mental health programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:253-258, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

69. Hammersley DW, Vosburgh P: Iowa's shrinking mental hospital population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 18:106-116, 1967 Link, Google Scholar

70. Lowry JV, Calais AM: Voluntary community treatment can prevent admissions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 18:236-237, 1967 Link, Google Scholar

71. Barnes RH: Maintaining chronic patients in the community. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 19:156-157, 1968 Link, Google Scholar

72. Stratas NE, Bernhardt DB, Elwell RN: The future of the state mental hospital: developing a unified system of care. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 28:598-600, 1977 Abstract, Google Scholar

73. State mental hospitals remain primary resource for treating schizophrenics. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:54, 1974 Google Scholar

74. Public opposition forces California's state hospitals to remain open. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:182-183, 1974 Google Scholar

75. Clayton T: The changing mental hospital: emerging alternatives. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:386-392, 1974 Abstract, Google Scholar

76. Massachusetts study proposes phase-out of state mental hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:492-493, 1974 Google Scholar

77. Ahmed PI, cited in Cochran B: Where is my home? The closing of state mental hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:393-401, 1974 Medline, Google Scholar

78. McAtee OB, Zirkle GA: In defense of the state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 27:585-586, 1976 Abstract, Google Scholar

79. Zaleski J, Gale MS, Winget Z: Extended hospital care as treatment of choice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:399-401, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

80. Ferguson SM: From snake pit to sanctuary: a positive look at the role of the public mental hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:486-487, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

81. Shore MF, Shapiro R: The effect of deinstitutionalization on the state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 30:605-608, 1979 Abstract, Google Scholar

82. Agnews, Mendocino state hospitals in California to close this summer. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 23(6):59, 1972 Google Scholar

83. California announces plan to close state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 24:349-350, 1973 Google Scholar

84. Ohio plans closing of 118-year-old Cleveland State Hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 24:567, 1973 Google Scholar

85. Hecker AO: The demise of large state hospitals: traditional facilities will be replaced by new kinds of treatment units. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 21:261-263, 1970 Link, Google Scholar

86. Abrams AL: Geographic unitization in large state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 22:285-287, 1971 Abstract, Google Scholar

87. Rollins RL, Stratas NE: The geographic unit as a phase in merging hospital and community programs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 25:378-380, 1974 Abstract, Google Scholar

88. Patch VD: Blacklisting mental hospital patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 21:269-271, 1970 Link, Google Scholar

89. Man PL, Elequin C: An analysis of applicants not admitted to a state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 22:380-381, 1971 Link, Google Scholar

90. Gunn RL, Pearman HE, Groth C, et al: Factors influencing release decisions. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 21:290-293, 1970 Link, Google Scholar

91. Linn LS: Measuring the effectiveness of mental hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 21:381-386, 1970 Link, Google Scholar

92. Erickson RC, Paige AB: Fallacies in using length-of-stay and return rates as measures of success. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 24:559-561, 1973 Abstract, Google Scholar

93. Altman H, Sletten IW, Nebel ME: Length-of-stay and readmission rates in Missouri state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 24:773-776, 1973 Abstract, Google Scholar

94. Schulberg HC: The mental hospital in the era of human services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 24:467-472, 1973 Abstract, Google Scholar

95. Jones M: State mental hospitals: demoralized, forgotten? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 29:610, 1978 Google Scholar

96. Miller RD: Beyond the old state hospital: new opportunities ahead. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:27-31, 1981 Abstract, Google Scholar

97. Okin RL: State hospitals in the 1980s. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:717-721, 1982 Abstract, Google Scholar

98. Taube CA, Thompson JW, Rosenstein MJ, et al: The "chronic" mental hospital patient. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:611-615, 1983 Abstract, Google Scholar

99. Craig TJ, Laska EM: Deinstitutionalization and the survival of the state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:616-622, 1983 Abstract, Google Scholar

100. Karras A, Otis DB: A comparison of inpatients in an urban state hospital in 1975 and 1982. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:963-967, 1987 Abstract, Google Scholar

101. Ozarin L: State hospitals as acute care facilities. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:5, 1989 Abstract, Google Scholar

102. Nelson SH, Vipond J, Reese K, et al: "Transfer trauma" as a legal argument against closing a state mental hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:1160-1162, 1983 Abstract, Google Scholar

103. Carling PJ, Miller S, Daniels LV, et al: A state mental health system with no state hospital: the Vermont feasibility study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:617-624, 1987 Abstract, Google Scholar

104. Taylor LD, Brooks GW: A screening program to reduce admissions to state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:59-60, 1980 Abstract, Google Scholar

105. DeFrancisco D, Anderson D, Pantano R, et al: The relationship between length of hospital stay and rapid-readmission rates. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:196-197, 1980 Medline, Google Scholar

106. Kinard EM: Discharged patients who desire to return to the hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 32:194-197, 1981 Abstract, Google Scholar

107. Shapiro JG: Patients refused admission to a psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34:733-736, 1983 Abstract, Google Scholar

108. Fisher WH, Geller JL, Costello DJ, et al: Projecting inpatient admissions to state facilities in the 1990s. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:747-749, 1989 Abstract, Google Scholar

109. Havassy BE, Hopkin JT: Factors predicting utilization of acute inpatient services by frequently hospitalized patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:820-823, 1989 Abstract, Google Scholar

110. Okin RL, Dolnick J: Beyond state hospital unitization: the development of an integrated mental health management system. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:1201-1205, 1985 Abstract, Google Scholar

111. Dittmar ND, Franklin JL: State hospital patients discharged to nursing homes: are hospitals dumping their more difficult patients? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 31:251-254, 1980 Google Scholar

112. Elpers JR, Crowell A: How many beds? An overview of resource planning. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 33:755-761, 1982 Abstract, Google Scholar

113. Gralnick A: Build a better state hospital: deinstitutionalization has failed. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:738-741, 1985 Abstract, Google Scholar

114. Okin RL: Expand the community care system: deinstitutionalization can work. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:742-745, 1985 Abstract, Google Scholar

115. Geller JL, Fisher WH, Kaye NS: Effect of evaluations of competency to stand trial on the state hospital in an era of increased community services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:818-823, 1991 Abstract, Google Scholar

116. Thompson JW, Belcher JR, DeForge BR, et al: Changing characteristics of schizophrenic patients admitted to state hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:231-235, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

117. Holobean EJ, Banks SM, Maddy BA: Patient subgroups in state psychiatric hospitals and implications for administration. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:1002-1004, 1993 Medline, Google Scholar

118. Fisher WH, Simon L, Geller JL, et al: Case mix in the "downsizing" state hospital. Psychiatric Services 47:255-262, 1996 Link, Google Scholar

119. Bloom JD, Williams MH, Land C, et al: Changes in public psychiatric hospitalization in Oregon over the past two decades. Psychiatric Services 49:366-369, 1998 Link, Google Scholar

120. Goodpastor WA, Hare BK: Factors associated with multiple readmissions to an urban public psychiatric hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:85-87, 1991 Abstract, Google Scholar

121. Casper ES, Romo JM, Fasnacht RC: Readmission patterns of frequent users of inpatient psychiatric services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:1166-1167, 1991 Abstract, Google Scholar

122. Geller JL: Treating revolving-door patients who have "hospitalphilia": compassion, coercion, and common sense. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:141-146, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

123. Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Forman SD, et al: Characteristics of repeat users of a psychiatric emergency service. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:376-380, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

124. Swett C: Symptom severity and number of previous psychiatric admissions as predictors of readmission. Psychiatric Services 46:482-485, 1995 Link, Google Scholar

125. Casper ES: Identifying multiple recidivists in a state hospital population. Psychiatric Services 46:1074-1075, 1995 Link, Google Scholar

126. Appleby L, Luchins DJ, Desai PN, et al: Length of inpatient stay and recidivism among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:985-990, 1996 Link, Google Scholar

127. D'Ercole A, Strueling E, Curtis JL, et al: Effects of diagnosis, demographic characteristics, and case management on rehospitalization. Psychiatric Services 48:682-688, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

128. Frazier RS, Casper ES: A comparative study of clinical events as triggers for psychiatric readmission of multiple recidivists. Psychiatric Services 49:1423-1425, 1998 Link, Google Scholar

129. Wasow M: The need for asylum revisited. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:207-208, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

130. Munetz MR, Peterson GA: SAFER houses for patients who need asylum. Psychiatric Services 47:117, 1996 Link, Google Scholar

131. Seling MJ, Johnson GW: A bridge to the community for extended-care hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:780-785, 1990 Abstract, Google Scholar

132. Kincheloe M: A state mental health system with no state hospital: the Vermont plan ten years later. Psychiatric Services 48:1078-1080, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

133. Edell WS, Hoffman RE, DiPietro SA, et al: Effects of long-term psychiatric hospitalization for young, treatment-refractory patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:780-785, 1990 Abstract, Google Scholar

134. Barber JW: Reflections on caring for the long-stay inpatient. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1023-1024, 1990 Abstract, Google Scholar

135. Gottheil E, Winkelman R, Smoyer P, et al: Characteristics of patients who are resistant to deinstitutionalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:745-748, 1991 Abstract, Google Scholar

136. Lamb HR, Shaner R: When there are almost no state hospital beds left. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:973-976, 1993 Abstract, Google Scholar

137. Geller JL: We still count beds. Psychiatric Services 48:1233, 1997 Link, Google Scholar

138. Blain D: Ideal mental health center discussed at World Health Organization meeting. Mental Hospitals 4(2):4-5, 1953 Google Scholar

139. Local care. APA Mental Hospital Service Bulletin 1(7):2, 1950 Google Scholar

140. Lehmann HE: New types of hospital-community facilities. Mental Hospitals 9(2):20-22, 1958 Google Scholar

141. Snow HB: Functions of the state hospital out-patient clinic. Mental Hospitals 4(6):7, 1953 Google Scholar

142. Williams DB: California experiments with half-way house. Mental Hospitals 7(1):24-25, 1956 Google Scholar

143. Eldred D: Problems of opening a rehabilitation house. Mental Hospitals 8(7):20-21, 1957 Google Scholar

144. Huseth B: Halfway houses: a new rehabilitation measure. Mental Hospitals 9(8):5-9, 1958 Google Scholar

145. Law M: All therapeutic activities available to day patients. Mental Hospitals 4(2):7, 1953 Google Scholar

146. Sloate N: Post-hospital care. Mental Hospitals 8(2):24-26, 1957 Google Scholar

147. Goshen CE: Expanding hospital services with the aid of community physicians. Mental Hospitals 9(9):10-11, 1958 Google Scholar

148. Hayes RH: A new community mental health program in eastern Kentucky. Mental Hospitals 10(4):9-11, 1959 Google Scholar

149. Discharge procedures and extramural planning. Mental Hospitals 11(2):27-37, 1960 Google Scholar

150. Waltzer H, Hankoff LD, Engelhardt DM, et al: Emergency psychiatric treatment in a receiving hospital. Mental Hospitals 14:595-600, 1963 Medline, Google Scholar

151. Leon RL: Community psychiatry starts with patients' needs. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:62-64, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

152. Ross M: Issues and problems in community psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:221-223, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

153. Beckerman A, Perlin S, Weinstein WB: The Montefiore program: psychiatry integrates with the community. Mental Hospitals 14:8-13, 1963 Medline, Google Scholar

154. Drubin L: Current practices and possible pitfalls. Mental Hospitals 11(1):26-28, 1960 Google Scholar

155. Gussen J: An experimental day-night-hospital. Mental Hospitals 11(6):26-29, 1960 Google Scholar

156. Colman A, Greenblatt M: "… Take up thy bed, and walk." Mental Hospitals 13:268-270, 1962 Medline, Google Scholar

157. Kantor D, Greenblatt M: Wellmet: halfway to community rehabilitation. Mental Hospitals 13:146-152, 1962 Medline, Google Scholar

158. Shearer RM: The structure and philosophy of Georgia's halfway houses. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 20:115-118, 1969 Link, Google Scholar

159. Kasprowicz AL: Needs of discharged patients. Mental Hospitals 11(4):9-12, 1960 Google Scholar

160. Pinsky S, Silverberg S, Weissman J: Resocializing ex-patients in a neighborhood center. Mental Hospitals 16:260-263, 1965 Medline, Google Scholar

161. Harrington C, Wilkins ML: Treating the social symptoms of mental illness. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 17:136-139, 1966 Link, Google Scholar

162. Meislin J: The need for an intermediary institution. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 20:88-89, 1969 Medline, Google Scholar

163. Sheeley WF: Community self-interest: wall or door? Mental Hospitals 11(7):17-19, 1960 Google Scholar

164. Edwards R, Paden W: Operation middleman. Mental Hospitals 12(3):21-23, 1961 Google Scholar

165. Quinn R, Van Dooren H: A low-cost community clinic. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 18:124-125, 1967 Link, Google Scholar

166. Greco JT: Action for community facilities. Mental Hospitals 12(5):13-15, 1961 Google Scholar

167. Ewalt JR: Needs of the mentally ill: types of effective action between the community and its hospital facilities. Mental Hospitals 12(2):12-15, 1961 Google Scholar