Moving Psychiatric Patients From Hospital to Community: Views of Patients, Providers, and Families

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Differences in the perspectives of severely and persistently ill patients, their family members, and clinical care providers on key aspects of community-based care were examined to help inform community service planning and development. METHODS: A sample of 183 patients being considered for relocation from psychiatric facilities in Alberta, Canada, to community-based care, were interviewed, as were their primary clinical care providers. Family members of 130 patients were also interviewed. RESULTS: Among the 130 patient-family pairs, 41 percent disagreed about the desirability of relocation, with fewer patients favoring relocation than families. Forty-nine percent of the pairs disagreed about the desired proximity to the family of the relocated patient, with the patient desiring closer proximity than the family member in about half of these cases. Fifty-three percent of the pairs disagreed about the amount of financial and emotional support that the family would provide after relocation. In half of these cases, patients believed the family would provide a higher level of support than the family indicated it could. Among the patients, 49 percent preferred independent living, whereas only 10 percent of family members and 17 percent of clinical care providers preferred it. Fifty-five percent of patients expressed a clear desire to work, whereas care providers believed that only 12 percent of patients were employable. CONCLUSIONS: Persistently mentally ill residents of psychiatric facilities express clear preferences about key aspects of community-based care when they are asked, and these preferences often reflect different views from those expressed by either family members or clinical care providers.

Few would debate the idea that mental health services should be designed to meet the needs of those they are intended to serve. Yet planners and researchers have consistently defined needs largely from the perspective of clinical experts without incorporating the perspectives of consumers or their families (1–6). Despite the importance of consumer and family perspectives, they have not yet gained wide acceptance as criteria against which changes in the organization, delivery, and financing of mental health care should be evaluated (7–10).

The importance of understanding multiple perspectives may be argued based on the increase in consumer-oriented and consumer-driven health care, the central role played by families in the community mental health paradigm (4), and the growing recognition that family burden can undermine consumers' success in living in the community (11). Understanding multiple perspectives may also have direct implications for improving key outcomes of care, such as community tenure.

A number of studies have now demonstrated that differences of opinion between consumers, family members, and their clinical caregivers do exist and that these differences can have important implications for key aspects of community functioning such as job tenure, housing preferences, or perceived social supports. For example, consumers who obtain jobs that correspond to their explicitly stated preferences are more satisfied with their jobs and remain in them longer than those who obtain jobs in nonpreferred areas (12). In addition, surveys of consumer populations indicate that they prefer independent accommodations of their own choosing that they do not have to share with other consumers. Yet clinicians typically recommend group living situations (5, 13–15).

Different views of the quality and characteristics of social support networks have also been documented. Stein and associates (16) found that compared with their families, consumers rated the quality of family interactions as lower and the relationships with family members as less supportive. However, Crotty and Kulys (17) reported that compared with families, consumers made more positive assessments of their networks, identifying more individuals, greater amounts of interaction, and higher degrees of support given and received. In the former study, congruence of agreement between consumers and family members was associated with consumer satisfaction, better psychological and social functioning, and lower levels of reported symptoms. Lack of congruence between consumers and their friends was characteristic of consumers who had more limited social contacts and lacked social involvement (18). Finally, Massey and Wu (4) found that consumers express more optimistic views about their abilities to function in the community than either their case managers or their family members.

Clinical staff, family members, and patients are all essential participants in the treatment planning process. The inevitable compromises that must be made to ensure patients' successful community placement can be reached only when each perspective is fully articulated and understood (4,5). To better understand and plan for the different perspectives of consumers, their family members, and clinical care providers, we compared their views on several key issues raised by a proposal to downsize psychiatric hospitals in Alberta, Canada, and relocate patients to community-based treatment alternatives. We were particularly interested in understanding levels of agreement between these groups on a range of issues, including the proposed relocation plan, preferred proximity to family, preferred living arrangements, perceived availability of social and financial supports, and work preferences.

This analysis was part of a larger study examining patients' potential for discharge and their support needs, which was commissioned by the planning body responsible for hospital downsizing (18). It was undertaken in an explicit attempt to incorporate the views of consumers and their families into the policy and planning process. Results of the larger study emphasized the importance of developing, implementing, and protecting community resources and of taking a cautious approach to bed closures.

Methods

The study included residents of Alberta's psychiatric facilities and care centers. These facilities had been targeted for significant downsizing; for example, some were to reduce the number of beds by 50 percent over a five-year period. General hospital psychiatric units were excluded from the study. The province's 2.5 million inhabitants are served by two large psychiatric hospitals—one in the north and one in the central portion of the province—and two rehabilitation centers located in the south of the province. Typically, these facilities address the needs of severely and persistently ill patients who require longer hospital stays. For example, at the time of the study (September 1995 to March 1996), 20 percent of the population in these facilities had been in residence there for more than five years, 14 percent between two and five years, 11 percent between one and two years, and 13 percent between three months and one year. The remaining 42 percent had been in residence for between one and three months.

Stays in these facilities are longer than those in general hospital psychiatric acute care units, where the average length of stay is usually between 18 and 20 days. In fiscal year 1992-1993, Alberta had approximately 42 facility-based psychiatric beds per 100,000 population (excluding general hospital psychiatric beds) compared with 82 per 100,000 for Canada as a whole. Residents in the two psychiatric hospitals accounted for 57 percent of the bed days of care for mental disorders, about the same as nationally (60 percent) (19).

The study methods are described in detail elsewhere (18), and only a brief summary is provided here. A cross-sectional survey was used to study a probability sample of 420 general psychiatric inpatients out of a total of 665 eligible subjects. This sample size permitted estimates to be accurate within 4 percent. Patients in highly specialized programs for forensic psychiatry (N=100), brain injury (N=65), and substance abuse (N=16) were considered to be ineligible for the study because they did not represent the groups for which community-based dispositions would ultimately be sought. Also, at the time of this research, separate needs assessments or planning initiatives were being considered for each of these groups.

This paper reports only on the 183 individuals in the representative sample considered potentially appropriate for relocation to community-based care. The primary clinical care provider for each patient judged the appropriateness of relocation based on the patient's legal status (whether or not the patient was involuntarily committed) and the patient's general functional abilities (ability to perform activities of daily living, personal hygiene skills, and ability to function in the community). Of these, 174 patients (95 percent) and 135 family members (74 percent) were interviewed, resulting in 130 patient-family pairs for analysis, which represented 71 percent of the patients who were originally considered appropriate for relocation. Nine patients did not consent to be interviewed, 31 had trustees or guardians appointed, and four had no family whatsoever. Eleven family members were unavailable during the study period, and two families did not agree to be interviewed.

The interviews were conducted between December 1995 and January 1996. Data were collected from patients and families by trained interviewers using a semistructured questionnaire that was partly based on existing instruments and partly developed to address the specific needs of the study. The pilot testing and data collection procedures received appropriate ethical and administrative approvals. To permit facility-specific analyses, all patients in the smaller care centers were oversampled. Because a stratified sampling design was used, all results are presented in the form of weighted frequencies and percentages.

Mental health care providers who were knowledgeable about the patients (the primary workers) were interviewed by the same trained interviewers using the semistructured questionnaire.

Results

A key aspect of the study was to ask patients and their families for their views on the desirability of community relocation. Patients and family members responded to a question asking how they felt about relocation; response categories were strongly agree, agree, indifferent, opposed, or strongly opposed. The majority of patients (75 percent of the 170 patients responding) strongly agreed or agreed with the idea of relocation from the facility to a community-based setting. A significant minority (18 percent) were strongly opposed or opposed, and a small proportion (7 percent) were indifferent. Primary care providers who were interviewed about relocation estimated that 17 percent of patients would be uncooperative with discharge planning and 6 percent very much so.

Compared with patients, a slightly smaller majority of family members were in favor of relocation (65 percent of 132). Family agreement was usually contingent on the availability of appropriate community treatment alternatives, a condition that families clearly and emphatically expressed to interviewers. Twenty-six percent of family members were opposed to relocation, and 10 percent were indifferent.

Despite apparently high levels of agreement-in-principle between patients and family members about relocation, agreement was not so pronounced when patient-family pairs were examined. Of the 130 patient-family pairs, 59 percent were in agreement about the desirability of relocation, with fewer patients favoring relocation than families. In 7 percent of cases, both family member and patient were opposed to relocation, and in 2 percent of cases, both were indifferent. Overall, 41 percent of the patient-family pairs disagreed about the desirability of relocation.

Patients and family members were also asked whether they would like to live close to each other after relocation. Three response categories were provided: yes, no, and uncertain. Almost half of the patient and family pairs (49 percent) disagreed about proximity, with the patient wishing to be closer than the family member in about half of these cases. Slightly more than a third of patients agreed with their family member that they would like to be close to each other (39 percent). Both parties were indifferent in 10 percent of cases, and both were opposed in 2 percent.

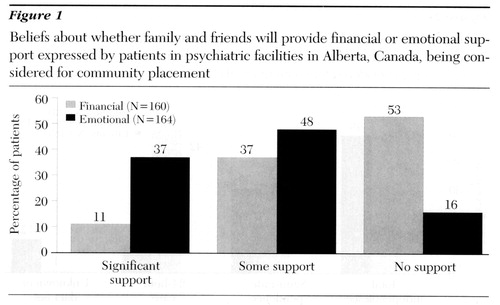

Given the importance of social support to community tenure, patients were also asked whether they felt they could rely on their family or friends for emotional support and financial support if they were relocated. Figure 1 shows that patients were more likely to believe that they would receive emotional support than financial support. It is noteworthy that more than half of the patients believed that they would receive no financial support whatsoever from family or friends. By comparison, only 16 percent believed they would receive no emotional support whatsoever.

In the interest of making consumers and families coparticipants in the research process, a consumer and family advisory committee provided feedback on all aspects of the study design and questionnaire items. They believed it would be upsetting for family members to be questioned directly about their ability to provide financial support for relocated relatives in light of the significant health, social service, and education cutbacks that had occurred in the province; for example, up to a third of some program budgets were cut. They believed that a direct question about financial status would be viewed as an attempt to shift health and social service supports from provincial agencies to families, many of whom would be ill equipped to handle the increased burden.

Thus family members were asked whether they believed they could provide “support and assistance” to their family member if he or she was relocated to the community. Of the 132 family members responding to this question, 37 percent believed that they could provide a “significant” amount of assistance, and another 54 percent believed that they could provide “some” assistance. Only 9 percent felt that they could not provide any assistance.

Although the wording of the social support question for the patients and families was not identical, which somewhat limits the comparison, 21 percent of 127 family-patient pairs agreed that a significant amount of support would be provided if the patient was relocated. In 24 percent of cases, both agreed that some support would be available, and in 2 percent of cases, both agreed that no support would be available. Fifty-three percent of the patient-family pairs disagreed about the amount of support. In half of these cases, patients thought that a higher level of support would be available than the family indicated it would be able to provide.

Patients were asked to indicate what type of housing they would need to live in the community successfully and avoid hospitalization. Responses were open ended. Clinical care providers and family members were asked to identify their first choice of living arrangement for the patient, and their responses were recorded using a structured format. Responses from both questions were analyzed to reflect preferences for independent living, semi-independent living, supervised or supported accommodations, and accommodations providing 24-hour supervision or a secure environment, such as a hospital or nursing home. All but 12 percent of patients were able to express a preference.

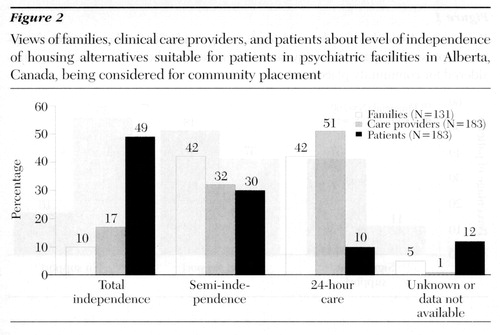

Patients expressed the desire to live independently more often than their family members or clinical care providers. Family members and clinical care providers favored situations that tended to limit independence, whereas patients favored situations in which their independence was maximized. Figure 2 shows that 49 percent of patients preferred independent living. By comparison, only 10 percent of family members and 17 percent of clinical care providers preferred independent living.

Finally, patients were asked to indicate whether they would want to work if they were relocated to the community. More than half of the patients (55 percent) expressed a clear desire to work, 38 percent were opposed, and 7 percent were uncertain. Using the same response categories (yes, no, or uncertain), clinical care providers were asked to indicate whether they thought each patient was employable. Care providers believed that 12 percent of the patients were employable and 82 percent were not employable, and they were uncertain about 6 percent of the patients. Further, they believed that if patients were successfully relocated to a community setting, at least half would require programs to provide intensive assistance to help them obtain and maintain employment, volunteer positions, or education and training.

Discussion and conclusions

We surveyed residents of psychiatric facilities in Alberta who were considered to be potentially relocatable to a community-based setting, as well as their families and their clinical care providers. Our results show that patients' views were considerably different from their family members' in many key aspects of community living, including the desirability of relocation to a community-based alternative, the desired degree of proximity to family members, and the degree of social support that would be available to the patient after relocation.

Patients also disagreed with family members and clinical care providers about the type of housing that would best support their community tenure. Patients more often expressed a desire to live independently, whereas family and clinical care providers more often chose a semi-independent setting or a 24-hour care facility. Finally, compared with clinical care providers, patients also expressed more optimistic views, or hopes, about their future work prospects. Although staff believed that most patients were not employable, more than half of the patients expressed a clear desire to work.

These results support the conclusions that even persistently mentally ill residents of psychiatric facilities express clear preferences about key aspects of community-based care when they are asked and that these preferences often reflect different views from those expressed either by family members or by clinical care providers.

This research made no assumptions about which perspective is “correct.” Rather, it is based on the dual principles that fostering consumer feedback and input into policy decisions and service delivery is fundamental to consumer empowerment and health promotion (20) and that the degree of congruence in the perspectives of consumers, family members, and clinical staff may have important implications for community success. Therefore, illuminating differences in perspectives is an essential first step in working toward their successful resolution (5).

The fact that consumers often expressed different and sometimes more optimistic views than either their clinical care providers or family members highlights the importance of explicitly incorporating multiple perspectives into service planning. That staff, and sometimes families, are more protective or cautious may reflect a pragmatic orientation that would restrict management goals to be consistent with the current availability—or unavailability—of services. If so, areas of agreement could form a strong foundation for individual care and management, and areas of disagreement could provide a basis for strategic planning, setting service priorities, and identifying areas that require service innovations.

However, for this approach to work, clear structures are needed to ensure that consumer and family feedback are routinely incorporated into planning activities and policy decisions. Alberta's Provincial Mental Health Advisory Board has identified the elicitation of multiple perspectives from consumers, their families, and community members as a primary goal of its core businesses. As well as using traditional survey techniques to obtain input, the board will maintain a ratio of 25 percent consumers and 25 percent family members on all regional mental health advisory committees (21).

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by the Provincial Mental Health Board.

Dr. Holley is assistant professor in the department of community health sciences of the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Calgary and is affiliated with the Calgary Regional Health Authority. When the research was undertaken, Ms. Hodges and Ms. Jeffers were working for the Calgary Mental Health Board. Ms. Hodges is now a private consultant, and Ms. Jeffers works for Alberta Health. Send correspondence to Dr. Holley at the Peter Lougheed Centre, Calgary General Hospital 3645, 3500 26th Avenue, N.E., Calgary, Alberta, Canada T1Y 6J4 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Beliefs about whether family and friends will provide financial or emotional support expressed by patients in psychiatric facilities in Alberta, Canada, being considered for community placement

Figure 2. Views of families, clinical care providers, and patients about level of independence of housing alternatives suitable for patients in psychiatric facilities in Alberta, Canada, being considered for community placement

1. Goering P, Paduchak D, Durbin J: Housing homeless women: a consumer preference study. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:790-794, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

2. Elliott SJ, Taylor SM, Kearns RA: Housing satisfaction, preference, and need among the chronically mentally disabled in Hamilton, Ontario. Social Science and Medicine 30:95-102, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Tanzman B: An overview of surveys of mental health consumers' preferences for housing and support services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:450-455, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

4. Massey OT, Wu L: Three critical views of functioning: comparisons of assessment made by individuals with mental illness, their case managers, and family members. Evaluation and Program Planning 17:1-7, 1994Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Minsky S, Gubman G, Duffy M: The eye of the beholder: housing preferences of inpatients and their treatment teams. Psychiatric Services 46:173-176, 1995Link, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

7. Franks D: Economic contribution of families caring for persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 18:9-18, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Andreasen NC: Assessment issues and the cost of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:475-481, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Capri S: Method for evaluation of the direct and indirect costs of long-term schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 89(suppl 382):80-83, 1994Google Scholar

10. Tessler R, Gamache G: Continuity of care, residence, and family burden in Ohio. Milbank Quarterly 71:149-169, 1995Google Scholar

11. Crotty P, Kulys R: Are schizophrenics a burden to their families? Significant other's views. Health and Social Work 119:173- 188, 1986Google Scholar

12. Becker DR, Drake RE, Farabaugh A, et al: Job preferences of clients with severe psychiatric disorders participating in supported employment programs. Psychiatric Services 47:1223-1226, 1996Link, Google Scholar

13. Owen C, Rutherford V, Jones M, et al: Housing accommodation preferences of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 47:628-632, 1996Link, Google Scholar

14. Goldfinger SM, Schutt RK: Comparison of clinicians' housing recommendations and preferences of homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:413-415, 1996Link, Google Scholar

15. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM: Housing preferences and perceptions of health and functioning among homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:381-386, 1996Link, Google Scholar

16. Stein CH, Rappaport J, Seidman E: Assessing the social networks of people with psychiatric disability from multiple perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal 31:351-367, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Crotty P, Kulys R: Social support networks: the views of schizophrenic clients and their significant others. Social Work 30:301-309, 1985.Crossref, Google Scholar

18. Holley HL, Jeffers B, Hodges P: Potential for community relocation among residents of Alberta's psychiatric facilities: a needs assessment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:750-757, 1997 Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Statistics Canada: Mental Health Statistics, 1992-93. Ottawa, Ministry of Industry, Science, and Technology, 1995Google Scholar

20. Lehman AF, Ward N, Linn L: Chronic mental patients: the quality of life issue. American Journal of Psychiatry 139:1271-1276, 1982Link, Google Scholar

21. Business Plan, 1997/1998 to 1999/2000. Edmonton, Alberta, Provincial Mental Health Advisory Board, 1997Google Scholar