Mental Health Consumers as Peer Interviewers

Abstract

Although consumers are increasingly hired as mental health workers, they typically fulfill demanding jobs such as case manager. This study examined the performance and job satisfaction of 18 consumers with serious mental illness who were hired for less demanding work—to conduct highly structured interviews with their peers. The consumers completed interviews with 243 peers. Only one interviewer was unable to perform the work. Ninety percent of the interviews were completed satisfactorily. Interviewers reported increased skills and knowledge, improved self-assurance, and feelings of pride. Results of the study suggest that a wide range of consumers can perform structured treatment tasks.

Employing consumers as mental health workers offers many advantages for consumers and employers (1,2,3,4,5,6). However, consumers have typically been hired for complex and demanding jobs such as case managers or job coaches, limiting the pool of competent workers to more experienced and skilled consumers.

The third author recently developed a highly structured assessment instrument that surveys an individual's treatment goals and current functioning (Wallace, unpublished manuscript, 1998). The results provide an empirical base for planning treatment and for evaluating its effects when ongoing assessments are conducted. Administration of the instrument requires only basic interviewing skills, and the interviewer and client can set up a time and place for the interview that meets their needs. The purpose of this study was to assess the job performance and satisfaction of consumers who were hired to administer the instrument.

Methods

Thirty-five individuals with serious and persistent mental illness (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or major depression) applied for a job as a peer interviewer after seeing advertisements posted at Project Return clubs. Project Return is a self-help organization run by and for mental health consumers. Seventeen of the 35 did not complete training due to physical illness, lack of interest, or insufficient time.

Of the 18 consumers who completed training, eight were female and ten were male. Two were African American, three Asian, eight Caucasian, one Hispanic, two of mixed racial background, one Native American, and one Pacific Islander. Data on age were not collected.

The interviewers were trained in three hours of didactic presentations and practice. The didactic material explained the purpose of the instrument, emphasized the importance of confidentiality, and described the personal qualities needed to conduct the interview. Practice interviews were then conducted, and all were audiotaped. The tapes were reviewed by the trainer, and feedback was given during an hour of individual supervision.

Each interviewer was given a list of Project Return members to contact who had agreed to be interviewed after seeing advertisements posted at the clubhouses. The interviewers were given copies of the interview forms, blank tapes, tape recorders, and time sheets to record their hours and expenses. All interviews were audiotaped so that the research team could confirm that the interview was performed and that procedures were followed. The interviewers were paid $5 an hour for training, supervision, and interviewing and were compensated for all transportation expenses. Typically, an interview lasted 60 to 90 minutes.

Interviewers were expected to complete the interviews within two weeks. They received a reminder phone call after one week and met with the supervisor (another consumer) or the trainer the week after the interviews were completed. The project spanned a nine-month period (June 1996 to March 1997), during which time the interviewers were offered ongoing supervision and support by both the supervisor and the trainer.

Each interviewer assessed between one and 32 clients. The mean±SD number for the 18 interviewers was 13.56±9.72. All interviewees gave written consent to the study, and all were paid $10 for the interview. A total of 243 clients were interviewed, of whom 203 were living in the community and 40 were inpatients on a locked unit at a skilled nursing facility.

Results

Task performance

Two of the 18 interviewers dropped out of the study due to transportation and financial hardships. Only one did not collect useful data for analysis, because of inability to use the recorder and to legibly note answers. The other 15 consumers were able to perform well despite their fluctuating symptoms.

The research team thoroughly examined all 243 taped interviews and the accompanying completed instrument. The interviewers' performance was assessed by comparing the written interviews with the corresponding tape recordings for quality and accuracy, as well as by the number of interviews completed within the allotted two weeks. In 218 interviews, or 90 percent, the interviewers performed with complete accuracy. One reason for the accurate performance was the interviewers' relative freedom to arrange the time and place of the interviews to maximize their comfort and attentiveness.

Given the extremely frustrating vagaries of the public transportation system and the occasional unreliability of the interviewees, the interviewers were quite hardworking, trustworthy, reliable, and good humored during the process. Furthermore, the interviewees voiced no complaints.

Work satisfaction

Immediately after termination of the study, the researchers asked the 18 interviewers to complete a questionnaire. One year later the researchers attempted to locate the 18 interviewers to complete the same questionnaire with supplementary questions. Fifteen interviewers returned the questionnaire immediately after the study, and the same 15 were located for follow-up a year later. No significant differences were found in gender, ethnicity, or diagnosis between the three interviewers who did not complete the study and the 15 who did.

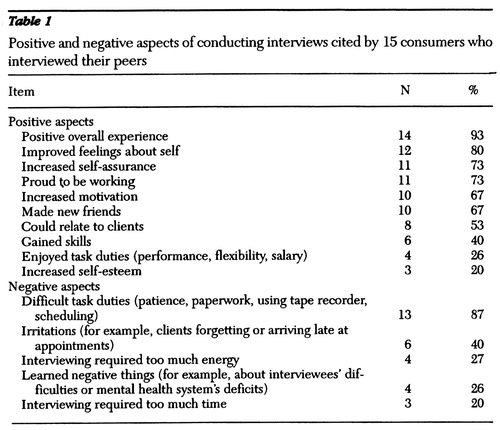

The questionnaire asked the interviewers what was positive and negative about the experience. Results are shown in Table 1. The questionnaire also addressed the amount of stress the interviewers experienced. Eight interviewers (53 percent) reported feeling less stress working with peers than with the general public, five (33 percent) reported that the stress was the same for peers and the general public, and only two (13 percent) stated that interviewing their peers caused more stress than they felt in working with the general public. Only one of the 15 interviewers reported not having liked the experience, expressing a preference for solitary paperwork.

Discussion and conclusions

The purpose of this study was twofold. First, the study sought to verify that consumers with little experience as mental health workers can accurately perform a structured task relevant to mental health treatment of their peers. Second, the study determined the interviewers' reactions to accomplishing the task.

Not only were consumers accurate and dependable workers, but most enjoyed the work and felt their lives had been enhanced by it. Furthermore, like the interviewees, the interviewers reported benefiting from the content of the assessment because it allowed them to reassess their own needs, desires, and goals in a more focused manner.

Work in the mental health field is attractive to many consumers. As a work environment, the mental health system is far less stigmatizing than other types of environments. It also offers consumers the chance to make friends and help their peers. Many consumers are not able to work as case managers, but they could learn the skills to quite competently perform well-structured treatment-relevant tasks such as client interviews. Mental health teams and support groups can create such work opportunities by dividing existing larger-scale jobs into smaller delimited tasks. The more structured the task, the more consumers can be empowered to work and to truly become part of collaborative team efforts.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Lecomte's work on this project was supported by a fellowship grant from the Conseil Quebec de Recherche Sociale. This work was partly supported by grant 30911 to the Intervention Research Center for Schizophrenia (Robert P. Liberman, M.D., principal investigator) from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Dr. Lecomte is a postdoctoral fellow in psychology at the Clinical Research Center for Schizophrenia at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Ms. Wilde is a research associate and Dr. Wallace is visiting professor of medical psychology at the UCLA Intervention Research Center for Schizophrenia. Address correspondence to Dr. Wallace at Psychiatric Rehabilitation Consultants, P.O. Box 2867, Camarillo, California 93011-6022 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Positive and negative aspects of conducting interviews cited by 15 consumers who interviewed their peers

1. Mowbray CT, Moxley DP, Thrasher S, et al: Consumers as community support providers: issues created by role innovation. Community Mental Health Journal 32:47-67, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Besio SW, Mahler J: Benefits and challenges of using consumer staff in supported housing services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:490-491, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Lyons JS, Cook JA, Ruth AR, et al: Service delivery using consumer staff in a mobile crisis assessment program. Community Mental Health Journal 32:33-40, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Solomon P, Draine J: The efficacy of a consumer case management team:2-year outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:135-146, 1995Google Scholar

5. Solomon P, Draine J, Delaney MA: The working alliance and consumer case management. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:126-134, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Felton CJ, Stastny P, Shern DL, et al: Consumers as peer specialists on intensive case management teams: impact on client outcomes. Psychiatric Services 46:1037-1044, 1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Solomon P, Draine J: Perspectives concerning consumers as case managers. Community Mental Health Journal 32:41-46, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Woodside H, Cikalo P, Pawlick J: Collaborative research: perspectives on consumer-professional partnerships. Canada's Mental Health 43:2-6, 1995Google Scholar