Rehab Rounds: Teaching Fundamental Workplace Skills to Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

Introduction by the column editors: Although only a minority of individuals with schizophrenia and disabling forms of other mental disorders find competitive employment, new legislation, public policies, and rehabilitation methods that are being developed promise to substantially increase that minority. For instance, the Americans With Disabilities Act has raised awareness that workers with mental disabilities are protected by federal law from discriminatory practices. In addition, the Social Security Administration has revised its policies to permit recipients of Supplemental Security Income to work part time without incurring a financial penalty. Similarly, partnerships between state agencies responsible for vocational rehabilitation and state and local departments of mental health have made it easier for individuals with mental disorders to use resources traditionally reserved for individuals with physical disabilities.An example of a newer clinical approach to vocational rehabilitation is supported employment. Clients in a supported employment program are placed in competitive employment as soon as possible and receive all the support services needed to learn and keep the job. A previous Rehab Rounds column described a supported employment program called Integrated Placement and Support (IPS), in which supported employment techniques and staff were fully integrated with psychiatric and psychosocial treatment (1). In a study comparing IPS with services provided by separate vocational rehabilitation agencies, IPS resulted in significantly more hours of work and more income for participants (2).However, two of the study's findings pointed to limitations in the effectiveness of the integrated services. First, the accuracy with which the services were implemented varied greatly, and the outcomes mirrored the inaccuracies. The less accurate the implementation, the poorer the outcomes. Second, supported employment showed no advantage over traditional vocational rehabilitation services in helping workers retain their jobs. The proportion of individuals employed at the end of 18 months of participation, the average duration of all jobs, and the average duration of the first job were no better for those enrolled in supported employment.To overcome these limitations, Charles Wallace and his colleagues developed a comprehensive and highly structured treatment, called the workplace fundamentals module, designed to teach mentally ill workers how to keep their jobs. In this month's column, they describe the format of the intervention, the development and validation process, and the results of a pilot study using the module. This module is one of the social and independent living skills modules developed by the UCLA Intervention Research Center, of which the second editor of this column (RPL) is director and principal investigator.

Like other modules in the UCLA social and independent living skills series, the workplace fundamentals module was formatted according to a design that has proven to be easily and accurately implemented by diverse practitioners working in a wide range of settings (3). Each module in the UCLA series is a self-contained curriculum that covers four to nine skill areas involved in a major domain of community functioning of persons with serious mental illness (4). The techniques used to teach the skills are based on a range of behavioral learning principles known to help individuals with serious and persistent mental illness overcome their learning disabilities. Each skill area is taught with seven learning activities—introduction to the skill area, videotaped demonstration of its constituent behaviors, role-played practice, practice in solving resource management problems, practice in solving outcome problems, in vivo assignments, and homework assignments.

Each module is distributed as a package of three components: a trainer's manual that specifies exactly what the trainer is to say and do, a demonstration videotape, and a participant's workbook with additional materials that help participants learn the material. A module is typically conducted with a trainer and four to eight participants. It is completed in eight to 12 weeks of biweekly 90-minute sessions. Modules may be flexibly adapted to the specific requirements and attributes of the participants and to the resources and constraints located in each clinical setting.

Development of the workplace fundamentals module

To ensure the comprehensiveness of the workplace fundamentals module, we conducted an extensive search of the relevant research and clinical literature and held detailed interviews with panels of stakeholders including workers with serious mental illness, clinicians, program managers, and employers. The review of the literature indicated that workers with mental illness generally had difficulties interacting with their coworkers and supervisors, managing their symptoms and medications, performing their specific job tasks, and maintaining satisfying work. In addition, they often had problems with abuse of alcohol and illicit drugs.

To validate the applicability of these problems to the project's locale and to develop the content for the intervention, we conducted extensive interviews with 35 staff members from agencies that purchased or provided vocational services, 11 employers who had hired persons with mental illness for competitive jobs, and 30 persons with mental illness who had been competitively employed at least once in the past five years. The respondents also completed several questionnaires. The interviews were audiotaped, and the responses to the open-ended questions were independently coded by two raters according to the worker, workplace, and support factors that were believed to result in successful or unsuccessful outcomes.

The coding confirmed and expanded the results of the literature review. Worker factors included difficulties managing symptoms and medications, job-related living supports such as transportation and clothing, performance of job tasks, and dependability. Workplace factors included task requirements, rewards, and interpersonal relationships. Support factors focused on the type of supporter such as a job coach and case manager.

The module's conceptual framework was then formulated: workers would be more likely to keep their jobs if, from the beginning of their employment, they identified the specific details of their workplaces—such as pay, timing of work and breaks, job tasks, peers—then matched them with their skills and preferences to identify mismatches and prospective stressors, used a standardized problem-solving method to develop solutions that might prevent or mitigate stress, and, with the support of a job coach, personalized and tried the solutions. Implementing this process was assumed to require nine skills, shown in the accompanying box.

Skill areas covered in the workplace fundamentals module

Identifying how work changes participants' lives

Learning about the expectations for performance on the job

Identifying personal strengths and preferences and determining mismatches with the job

Learning how to use a general problem-solving method to cope with stressors

Using problem solving to manage symptoms and medications at the workplace

Using problem solving to manage general health concerns and deal with substance use as it affects the workplace

Learning how to interact with supervisors and peers to improve job task performance

Learning how to socialize successfully and with low stress with coworkers

Using problem solving to recruit social support on and off the job

Assumptions and adaptations

Because the workplace fundamentals module was specifically intended to teach workers how to keep their jobs, it was assumed that participants would have a job—or would soon have one—and would have enough cognitive functioning to understand and perform their actual or anticipated job tasks. No other individual characteristics—such as diagnosis, work history, age, gender, ethnic identification, or amount of social support—would exclude participants. Furthermore, given general clinical practices and research findings suggesting the importance of continued support (5), no participant was expected to go it alone in getting and keeping a job. Thus the workplace fundamentals model was designed at the outset to be fully integrated with supported employment services, particularly those that were themselves integrated with psychiatric services.

It was also anticipated that the workplace fundamentals module could be conducted by any clinical staff member, making its benefits widely available to potential workers and allowing supported employment staff to focus on helping participants adapt the skills to their specific workplaces. However, this division of tasks added a level of complexity that makes timely and comprehensive communications among the stakeholders critical to the success of the intervention.

To channel and structure these messages, the participant's workbook was renamed the JOB (job organizing book), printed as a large day planner, and filled with blank worksheets that participants would complete during their in vivo or homework assignments in each skill area. On these worksheets, participants described how their characteristics and those of their workplaces might affect the implementation of the skills they were learning in each skill area of the module. When participants needed to use a skill in their workplaces, their job coaches reviewed the applicable worksheets and helped participants implement the precise skill necessary for successful adjustment. The sheets were used to record notes about the implementation, were reviewed by other staff and participants, and were updated to reflect changes in participants' jobs and workplaces.

Implementation

Participants were selected from the roster of individuals served by a contract vocational agency. Clinicians were asked to nominate both employed and unemployed individuals whose schedules did not conflict with that of the project. The unemployed individuals were included to determine whether the workplace fundamentals module might be useful for acquainting them with the ins and outs of the workplace before employment. Among the agency's 45 cases, ten employed and ten unemployed individuals were nominated; six in each group agreed to participate. Four of the eight who declined had conflicts in their schedules, and four were not interested in the project.

One group was formed with the six employed individuals, and another with the six unemployed individuals. One participant in each group withdrew from the project, one because of medication changes that led to a relapse, and the other to comply with a spouse's request not to work.

Of the five remaining employed participants, three were men and two were women. Their average age was 34 years. Three had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and two had major affective disorder. One was currently married; the others were single. The five remaining unemployed participants included three men and two women. Their average age was 35 years. Four had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and one had major affective disorder. One of the five was divorced; the others were single.

Assessment and results

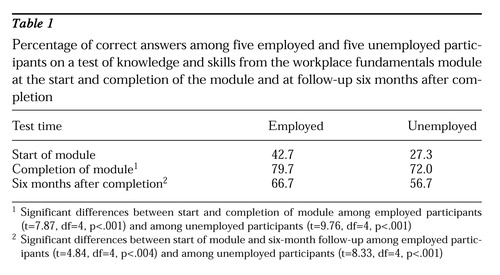

The dependent measures included a test of the knowledge and skills taught in the module and two measures of work: hours worked per day and days of any work. The dependent measures were administered at the beginning of the module, at its completion three months later, and six months after completion. The data were analyzed with the SPSS statistical package. Each dependent measure was analyzed separately for the employed and unemployed groups using one-way repeated-measures analyses of variance, with time—beginning and completion of the module and follow-up—as the independent variable. Both F ratios were significant, and the results were further analyzed with Bonferroni adjusted t tests.

As shown in Table 1, both groups significantly and substantially improved their knowledge of the material and performance of the skills taught in the module. Scores were somewhat lower at the follow-up testing, although they were still significantly higher than the pretest scores.

The employed group worked an average of 33 days and 117.4 hours during the three months of training, and 32.8 days and 133.7 hours during the six-month follow-up period. All continued their employment for the entire nine months of the project, the longest period of employment ever for four of the five participants. Three unemployed participants obtained and kept jobs during the follow-up period; however, the average number of days of employment and the average number of hours worked in the unemployed group were considerably lower than in the employed group.

These results are particularly encouraging because this pilot study of the workplace fundamentals module was conducted with only informal and irregular contact between the project and the agency's clinicians. Of course, the quasiexperimental design used in this evaluation does not allow attribution of these outcomes to the workplace fundamentals module. A rigorous evaluation of the module is under way; it involves 48 participants randomly assigned to receive integrated supported employment services alone or in combination with the module. Participants will be monitored for 18 months, with both vocational and clinical measures of outcome.

Afterword by the column editors:

The proportion of the population with serious and persistent mental illnesses such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder who are working in competitive, "real-life" jobs has not appreciably changed during the past few decades. A review published in 1972 found that less than 30 percent of persons with serious mental illness ever work, even in sheltered or transitional employment, and that fewer retain these sheltered jobs if they do get them (6). A large-scale study of more than 450 patients sponsored by the Social Security Administration found that less than 12 percent of persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder obtained jobs in the competitive sector, even after receiving training in job-finding skills; in comparison, more than 40 percent of individuals with major depression and 50 percent of those with substance abuse or dependence were successful in getting jobs (7).

These dismal statistics stand in contrast to the more optimistic findings reported with the introduction of supported employment, in which patients are placed in jobs and then trained to do the jobs. Using this "place, then train" strategy, about 50 percent of persons with serious mental illness can work in competitive jobs; unfortunately, only half of those who secure jobs are still working at those jobs six months later (1).

The workplace fundamentals module, for which early promising results are reported in this article, has been specifically designed and targeted for this population of workers, with the aim of promoting their sustained employment. Controlled studies to evaluate this module's efficacy when paired with supported employment are now under way at the UCLA Center for Research on Treatment and Rehabilitation of Psychosis. The studies involve a spectrum of persons with schizophrenia—both those in their first episode and those with more chronic disorders.

Dr. Wallace is visiting professor of medical psychology and Mr. Tauber and Ms. Wilde are research associates in the department of psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, Neuropsychiatric Institute. Address correspondence to Dr. Wallace at 9259 Louise Avenue, Northridge, California 91325-2426 (e-mail, [email protected]). Alex Kopelowicz, M.D., and Robert Paul Liberman, M.D., are editors of this column.

|

Table 1.

Percentage of correct answers among five employed and five unemployed participants on a test of knowledge and skills from the workplace fundamentals module at the start and completion of the module and at follow-up six months after completion

1. Drake RE, Becker DR: The Individual Placement and Support model of supported employment. Psychiatric Services 47:473-475, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Drake RE, McHugo GJK, Becker DR, et al: The New Hampshire study of supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:391-399, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Wallace CJ, Liberman RP, MacKain SJ, et al: Effectiveness and replicability of modules for teaching social and instrumental skills to the severely mentally ill. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:654-658, 1992Link, Google Scholar

4. Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, et al: Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA social and independent living skills modules. Innovations and Research 2:43-60, 1993Google Scholar

5. Bailey EL, Ricketts SK, Becker DR, et al: Do long-term day treatment clients benefit from supported employment? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:24-29, 1998Google Scholar

6. Anthony WA, Buell GJ, Sharratt S, et al: The efficacy of psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychological Bulletin 78:447-456, 1972Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Liberman RP, Mintz J: Psychopathology and the Functional Capacity for Work. Final report submitted to the Social Security Administration, June 30, 1998. Available from the first author at Community and Rehabilitation Psychiatry (116AR), West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 11301 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, Calif, 90073Google Scholar