Medication Adherence Among Psychotic Patients Before Admission to Inpatient Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Nonadherence to antipsychotic regimens is considered to be one of the main reasons for hospital readmission. This study assessed the extent of nonadherence in the month before inpatient treatment. METHODS: Ninety-five consecutive patients with an ICD-10 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (F20) were surveyed about adherence at admission to psychiatric inpatient treatment at a hospital in Linz, Austria. Adherence was assessed on the basis of self-report and by interviewing multiple informants. Episodes of inpatient treatment during the year after discharge were assessed prospectively. RESULTS: Fifty-four patients (57 percent) were rated as partially or fully nonadherent. Compared with patients with good adherence, those who were nonadherent had lower mean scores on the Global Assessment of Functioning (41.4 compared with 47.2), more often received compulsory treatment (52 percent compared with 22 percent), more often had impaired insight into their illness at admission (63 percent compared with 24 percent) and discharge (41 percent compared with 13 percent), and had more days of inpatient treatment in the year after discharge from the index episode (mean of 44.8 days compared with 20.6 days). Adherence was significantly better among patients in regular contact with their psychiatrist and among younger patients. Nonadherent patients who gained insight during treatment had significantly fewer days of inpatient treatment during the next year than those whose insight was still low at discharge (mean of 19.2 days compared with 73.2 days). CONCLUSIONS: Nonadherence is an important contributor to the need for inpatient treatment and is associated with a less favorable course of treatment. The best predictor of further inpatient treatment is insight into illness at discharge.

Antipsychotics are highly effective in reducing the risk of relapse among psychotic patients. A meta-analysis of controlled trials with a mean follow-up period of 9.7 months found cumulative relapse rates of 16 percent among patients who were maintained on antipsychotics, compared with 53 percent among patients whose antipsychotic therapy was withdrawn (1).

The favorable rates of relapse prevention found in controlled trials usually cannot be transferred to everyday practice. One of the most important factors responsible for this discrepancy is lack of cooperation by the patient. Cramer and Rosenheck (2) calculated a mean rate of adherence to antipsychotic regimens of 58 percent (range, 24 percent to 90 percent). Although reluctance to comply with prescriptions seems to be a human trait and nonadherence is a ubiquitous problem in medicine (3), some aspects of schizophrenia might make it especially difficult for patients to adhere to treatment.

First, schizophrenia is an illness in which insight is probably more likely to be impaired than is the case with other illnesses. Impaired insight not only is one of the most common symptoms of schizophrenia (4) but also has been proven in many studies to be associated with nonadherence to medications (5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12) and psychosocial treatment (13). Second, disorganization and cognitive disturbances are additional symptoms of schizophrenia that interfere with regular intake of medication (14,15,16).

In addition, schizophrenia's chronic course often requires lifelong medication. As a general rule, the longer the medication treatment period, the lower the rates of adherence. This problem has also been noted with other chronic diseases (17,18,19,20). Finally, schizophrenia and antipsychotics are subject to stigma. The use of antipsychotics is hampered by side effects that make patients more reluctant to follow prescriptions, a reality that apparently has not improved substantially with the advent of atypical antipsychotics (21,22). Some patients think that the easiest way to alleviate stigma is to stop treatment (23).

Most studies of adherence have investigated rates of adherence after initiation of treatment. We were interested in the role of adherence—or nonadherence—before inpatient treatment. From a practical point of view this issue is of some importance. First, admissions due to nonadherence are avoidable, at least from a theoretical point of view, and represent a great opportunity for savings. Second, it is necessary to tackle the issue of nonadherence during the inpatient stay for the sake of success of further treatment. Despite the overwhelming amount of literature on adherence, few studies have explored adherence at admission to inpatient treatment (24,25,26).

The aim of our study was primarily to assess the extent of nonadherence at admission to inpatient treatment, to determine how nonadherence was related to other demographic and treatment factors, and to assess the readmission rates of the patients during the year after discharge.

Methods

This study was conducted in a department of a psychiatric hospital responsible for an urban catchment area of about 200,000 inhabitants in Linz, Austria. Every patient with an ICD-10 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (F20) during the study period (December 1998 to June 1999) was included. Patients who were admitted for the first time, who had no previous recommendation for treatment, or whose medication regimen was unknown were excluded. We assessed the extent to which the patients had followed this recommendation in the last month before admission. Ratings were conducted by the psychiatrist who was in charge of the patient during inpatient treatment. The psychiatrists were trained on several occasions to ensure the interrater reliability of the scales used.

We assessed the extent to which the patients had followed treatment recommendations in the last month before admission primarily on the basis of the interview with the patient. If patients said that they had been nonadherent, they were rated thus. Otherwise, additional reports were obtained from psychiatrists, general practitioners, or relatives. If one of these individuals severely doubted the patient's adherence, a rating of nonadherent was adopted. When no clear decision was possible as a result of using this method, the patient was excluded from the study. Information about the prescribed drugs was obtained from the patient, hospital data files, or the physicians who had treated the patients previously. Medications were divided into the categories of conventional and atypical antipsychotics, depot antipsychotics, antidepressants, tranquilizers, and mood stabilizers. Intake was divided into three categories: as prescribed, less than prescribed, and not at all. For most statistical analyses, adherence ratings were dichotomized as adherent (as prescribed) or nonadherent (less than prescribed or not at all).

Severity of illness was rated by using the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) (27). Social functioning was rated by using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (28). Insight into illness was assessed by using the definitions provided by the 7-point scale for the item "lack of judgment and insight" contained in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (29). For some of the statistical analyses insight was dichotomized as "good" (if impairment was not present or was mild) and "poor" (if impairment was medium to extreme).

According to common treatment recommendations, the dosage range for antipsychotic maintenance therapy is 300 to 600 mg of chlorpromazine a day (30); 125 mg is considered a minimal maintenance dosage (31). Therefore, maintenance dosages of 200 to 100 mg of chlorpromazine were rated as questionable, and those lower than 100 mg were rated as insufficient.

Patients were followed for one year after the index admission, and the number of admissions to inpatient treatment and the number of days spent in inpatient treatment were counted. Bivariate comparisons were made by using chi square tests with continuity correction for nominal variables and t tests for continuous variables. To identify variables associated with adherence, a logistic regression analysis (stepwise forward procedure) using adherence as a dependant variable was performed. To identify variables associated with the number of days of inpatient treatment in the year after discharge, we performed a multiple linear regression (forward procedure). Because of the potential for a skewed distribution of the number of days of inpatient treatment in the year after discharge, we used the natural logarithm for multiple regression. Data were analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (32).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the province of Upper Austria. Because the study did not cause any change in clinical routine, no written informed consent was necessary under Austrian law.

Results

Characteristics of the total sample

A total of 105 consecutive patients were eligible for the study. For ten patients it was not possible to evaluate adherence to antipsychotic regimens with sufficient accuracy. Thus these patients were excluded from the analyses, leaving a sample of 95. The patients' mean±SD age was 39.2±11.1 years, and their mean duration of illness was 13.5±9.5 years. Diagnoses were paranoid schizophrenia (41 patients, or 43 percent), schizoaffective disorder (37 patients, or 39 percent), and residual type schizophrenia (ten patients, or 11 percent). Fifty-nine patients (62 percent) were men. No significant differences between sexes were found in the major variables, except for mean age (37±9.5 years for men and 42.8±12.1 years for women, t=2.50, df=93, p=.01), mean length of stay (16.3±11.3 days for men and 28.7±22 days for women, t=3.56, df=93, p<.001), and substance abuse (23 percent of men and 6 percent of women, χ2=3.67, df=1, p=.05). Before hospital admission, 76 patients (80 percent) received psychopharmacologic treatment from psychiatrists in private practice; this is the most common type of psychiatric outpatient care in the region. Thirty-three patients (35 percent) attended outpatient treatment centers, which in this region do not provide medical treatment but counseling, case management, and psychotherapy.

Adherence to drug regimens

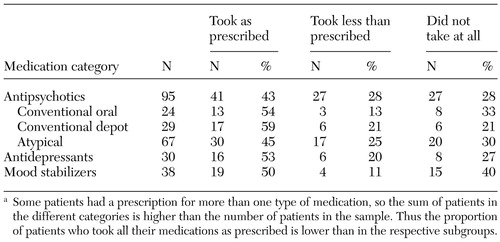

Rates of adherence to the different categories of medications are shown in Table 1. Overall adherence to antipsychotics was found among 41 patients (43 percent). Adherence did not differ significantly by medication category.

Patients who had paranoid schizophrenia took their antipsychotics somewhat more often as prescribed than patients who had schizoaffective disorders—18 patients (44 percent) compared with 12 patients (36 percent)—although this difference was not statistically significant.

Recommended dosages

For 15 patients (16 percent), the chlorpromazine dosage was between 200 and 100 mg of chlorpromazine. For 11 patients (12 percent), the dosage was below 100 mg. Dosages did not differ between patients who visited their psychiatrist regularly and those who did not. Of 41 patients who were taking their antipsychotics as prescribed, 13 (32 percent) had a dosage that was considered questionable or insufficient.

Fifteen (58 percent) of the patients with these low dosages had acquired their regimens by exerting pressure on their physicians. Whereas this was the case for only three (23 percent) of the patients with good adherence, it was true of 12 patients (92 percent) in the group with poor adherence (χ2=10.09, df=1, p=.002).

Comparison of patients with good and poor adherence

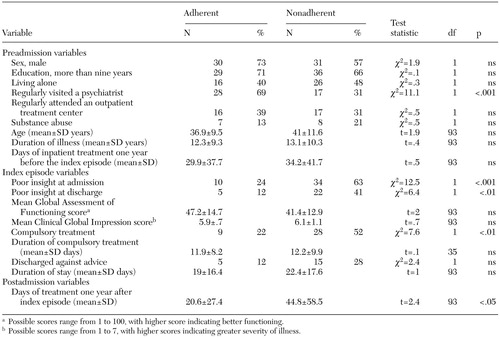

Characteristics of patients who took their antipsychotics as prescribed and those who were nonadherent or only partially adherent are summarized in Table 2. Women tended to be somewhat less adherent than men, although the difference was not statistically significant. Only 16 patients (15 percent) had a diagnosis of substance abuse, which did not correlate significantly with nonadherence.

Insight into illness was significantly worse among nonadherent patients than among other patients, both at admission and at discharge. Nevertheless, improvement in insight among nonadherent patients from admission to discharge was highly significant (χ2=12.46, df=1, p<.001).

To identify variables associated with adherence at intake, a logistic regression analysis was performed, with the independent variables sex, age, education, type of housing, duration of illness, whether the patient regularly visited a psychiatrist, whether the patient regularly attended an outpatient treatment center, number of psychiatric hospital admissions during the previous year, length of inpatient stay during the previous year, number of antipsychotics prescribed before admission, overall number of drugs prescribed before admission, antipsychotic dosage (sufficient or insufficient), type of antipsychotic (atypical or conventional), and diagnosis (schizophrenia or one of the other diagnoses). Adherence was significantly higher among patients who had regular contact with their psychiatrist (adjusted odds ratio [OR]= 2.028, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.185 to 3.470, p=.001) and among younger patients (adjusted OR=.940, CI=.886 to .998, p=.043). Because of the problem of multicolinearity—the duration of illness was strongly correlated with age, and the number of hospital admissions during the previous year was strongly associated with duration of treatment during the previous year—we performed additional regression analyses that excluded each of these variables in turn; the results remained stable throughout all analyses.

Hospitalization after one year

Compared with patients who adhered to their medication regimens, nonadherent patients were hospitalized for significantly longer periods during the year after the index episode, as can be seen in Table 2. In addition, insight into illness as rated at discharge showed a significant correlation with hospitalization in the next year: patients who had good insight were hospitalized for an average of 19.5±28.3 days, and patients with poor insight were hospitalized for 57.5± 60.8 days (t=4.1, df=90. p<.001). Patients who had been nonadherent at admission and who were discharged with a rating of good insight had a significantly better prognosis than those who had a rating of poor insight (19.2±28.9 days of treatment during the next year compared with 73.2±69.3 days, t=3.7, df=46, p<.001).

A multiple linear regression was performed to identify variables associated with days of inpatient treatment during the year after discharge; the independent variables were adherence to antipsychotic regimens, sex, age, education, duration of illness, length of inpatient treatment during the previous year, diagnosis (schizophrenia or one of the other diagnoses), insight at discharge, compulsory inpatient treatment at index episode, and discharge from the index episode against advice. Of all the independent variables that were included in the multiple regression, only insight at discharge was associated with number of inpatient days in the year after discharge (regression coefficient=1.093, CI=1.694 to .491, p=.001). Because of the problem of multicolinearity between insight at discharge and adherence, we performed additional regression analyses that excluded both variables in turn; the results remained stable.

Discussion and conclusions

Interpretation of results

We found that only 43 percent of the patients in this study took their antipsychotic medications as prescribed. Other groups that have investigated adherence before admission found comparable but still lower rates of adherence: 15 percent (24), 28 percent (26), and 34 percent (25). In our study, type of drug (conventional versus atypical antipsychotic and antipsychotic versus tranquilizer versus antidepressant) was not a factor in adherence.

Sociodemographic characteristics did not differ much between patients who had good adherence and those who had poor adherence, which is in line with the results of most other studies. Logistic regression showed that younger age was positively correlated with good adherence. The literature is equivocal about age, with studies finding good adherence more often among younger patients (33,34) as well as older patients (15,35). A further highly significant finding was that having regular visits to a psychiatrist was correlated with good adherence. Not visiting a psychiatrist might be viewed as just another aspect of nonadherence. Yet another possible inference from this result is that regular visits to a psychiatrist serve as a protective factor against nonadherence. Substance abuse, usually considered one of the most important reasons for nonadherence (9,12), did not play a major role in our sample, given that it was found among only 15 percent of patients.

Severity of illness at hospital admission was higher among the nonadherent patients when assessed with the GAF but not when assessed with the CGI. Previous studies that investigated the psychopathology of adherent and nonadherent patients in greater detail found that overall scores did not differ very much but that nonadherent patients had higher scores on psychotic symptoms, whereas adherent patients had higher scores on depression and anxiety items (25,36,37).

Patients with poor adherence had a less favorable course of treatment than those with good adherence, indicated by much higher rates of compulsory treatment during the index episode and longer duration of inpatient treatment during the next year, a finding that is in accordance with those of other authors (36,38,39).

Nonadherent patients had lower insight ratings at admission. This is an ambiguous finding, because poor insight can be a result of nonadherence as well as a cause. However, insight improved greatly among formerly nonadherent patients by the end of the index episode. Patients who were discharged with a rating of good insight did not differ in terms of time spent in inpatient treatment during the next year, regardless of whether they had been adherent at the index admission. Yet they spent significantly less time in inpatient treatment than did patients who were discharged with a rating of poor insight (19.5 compared with 57.5 days). So although nonadherence before admission as a whole was associated with an unfavorable course of illness during the next year, this finding applied only to the subgroup of patients who continued to have poor insight, whereas those who gained insight had a much better prognosis.

The greater importance of insight at discharge relative to that of adherence before admission was confirmed by a multiple regression analysis using days of inpatient treatment during the next year as the dependent variable—insight at discharge was the sole significant factor. This finding replicates the results of some other studies (5,35,37,40), which also stressed the high predictive value of insight at discharge.

Limitations of study design

Assessment of adherence is difficult. Patients' reports are often not considered reliable (14,34,41), and more sophisticated procedures—such as pill counts, drug monitoring, and microelectronic monitoring systems—have been recommended (2). Given that all methods have their pitfalls and most of them were inapplicable in our naturalistic study, we decided to rely on clinical judgment in conjunction with patient interviews and outside data sources. Use of multiple informants was recommended as a way of compensating for the methodologic limitations inherent in interviewing patients with schizophrenia (40).

In general, we found that most patients were frank about their nonadherence. If the patient reported having been adherent, we contacted the patients' relatives and treating physicians to get additional information. We are aware that all these data are subjective and may be biased for various reasons, and we regard our results as representing the minimum level of nonadherence. That is, we are quite sure that the patients we rated as nonadherent were indeed nonadherent and that we might have missed some cases of nonadherence by rating some patients as adherent when they were not.

Because the study was conducted under everyday working conditions, resources were limited, and in planning the study we had to choose between accuracy and feasibility. All ratings were done by the psychiatrist in charge of the patients. The quality of the data would have been better if the raters had been blinded to the adherence status of the patients. Also, no extensive, time-consuming rating scales could be applied. The assessment of insight based on the 7-point scale of the PANSS, which covers a broad concept of insight, provides less accuracy than a multidimensional scale might have done. On the other hand, the strong correlation between poor insight and rehospitalization might be an indicator of the clinical usefulness of the scale.

Implications for treatment

Thirteen (32 percent) of the adherent patients were taking a dosage of antipsychotics that was considered questionable (200 to 100 mg of chlorpromazine) or insufficient (less than 100 mg) to protect against relapse, which reduced the number of patients who were receiving adequate therapy to 28 (29 percent of the total group). It might be considered somewhat arbitrary to pinpoint these dosages as questionable or insufficient without knowledge of individual patients. Nevertheless, it is of clinical importance to know that more than a quarter of all patients who were admitted for inpatient treatment because of a psychotic relapse were receiving such low dosages.

There are two main explanations for these findings. First, psychiatrists are increasingly striving to keep antipsychotic dosages low (42), especially since it became evident that higher dosages foster side effects but are usually no more effective than lower ones (31,43,44). Second, having a low dosage prescribed is just another aspect of nonadherence: all except one patient with poor adherence had exerted pressure on their physician to reduce dosages. Of course, keeping the dosage as low as possible is a viable strategy for improving adherence. Yet our data show that this strategy is a problematic one. On one hand, the risk of relapse increases; on the other hand, many of the patients who press for a very low dosage will not comply with even that.

Promoting insight seems to be the most important lesson from our study, given that patients who gained insight had a much more favorable course in terms of hospitalization during the next year. Psychoeducation seems to hold some promise (45), yet effect sizes in terms of improvement in insight or adherence are mostly modest (8,46). Beyond this we are convinced that improvement in insight and further adherence is not only a matter of distinct treatment techniques but also a matter of convincing patients that the therapeutic efforts are aimed at achieving the very best outcomes for them, which requires a broad array of interventions and attitudes. Clearly there is much more research to be done, and further improvement in quality of treatment facilities is warranted.

Nonadherence has not only therapeutic implications but also important economic ones. Considering together both patients with poor adherence and patients who were adherent but whose dosage was too low, 71 percent had no adequate therapy before admission. There is much room for improvement given that patients who are receiving a sufficient dosage of antipsychotics have only about a fifth the risk of relapse of patients who are not taking antipsychotics (47). Weiden and Olfson (48) estimated that the costs of hospitalization due to nonadherence amounted to $800 million in the United States in 1993 dollars. Improving adherence is thus not only a therapeutic challenge but also a rewarding goal for both therapeutic and economic reasons.

Dr. Rittmannsberger, Dr. Pachinger, and Dr. Keppelmüller are affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the Wagner-Jauregg Clinic in Linz, Austria. Dr. Wancata is with the department of psychiatry at the University of Vienna in Austria. Send correspondence to Dr. Rittmannsberger at Nervenklinik Wagner-Jauregg, Wagner-Jauregg-Weg 15, A-4020 Linz, Austria (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Adherence to medication regimens in a sample of 95 patientsa

a Some patients had a prescription for more than one type of medication, so the sum of patients in the different categories is higher than the number of patients in the sample. Thus the proportion of patients who took their medications as prescribed is lower than in the respective subgroups.

|

Table 2. Characteristics of patients who took their medications as prescribed (adherent) and those who took less than prescribed or did not take their medications at all (nonadherent)

1. Gilbert PL, Harris MJ, McAdams LA, et al: Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients: a review of the literature. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:173–188, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 49:196–201, 1998Link, Google Scholar

3. Powsner S, Spitzer R: Sex, lies, and medical compliance. Lancet 361:2003–2004, 2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carpenter WT, Strauss JS, Bartko JJ: Flexible system for the diagnosis of schizophrenia: report from the WHO international pilot study of schizophrenia. Science 182:1275–1278, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Bartko G, Herczeg I, Zador G: Clinical symptomatology and drug compliance in schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 78:74–76, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

6. Ghaemi SN, Pope HG: Lack of insight in psychotic and affective disorders: a review of empirical studies. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 2:22–33, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. McEvoy JP, Freter S, Everett G, et al: Insight and the clinical outcome of schizophrenic patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:48–51, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. McEvoy JP: The relationship between insight in psychosis and compliance with medication, in Insight in Psychosis. Edited by Amador XF, David AS. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1998Google Scholar

9. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Hansell S, et al: Predicting medication noncompliance after hospital discharge among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:216–222, 2000Link, Google Scholar

10. Schwartz RC, Cohen BN, Grubaugh A: Does insight affect long-term inpatient treatment outcome in chronic schizophrenia? Comprehensive Psychiatry 38:283–288, 1997Google Scholar

11. Trauer T, Sacks T: The relationship between insight and medication adherence in severely mentally ill clients treated in the community. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 102:211–216, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lacro JP, Dunn LB, Dolder CR, et al: Prevalence and risk factors for medication nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 63:892–909, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lysaker P, Bell M, Milstein R, et al: Insight and psychosocial treatment compliance in schizophrenia. Psychiatry 57:307–315, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Babiker IE: Noncompliance in schizophrenia. Psychiatric Developments 186:329–337, 1986Google Scholar

15. Bebbington PE: The content and context of compliance. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 9(suppl 5):41–50, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

16. Marder SR, Mebane A, Chien C, et al: A comparison of patients who refuse and consent to neuroleptic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:470–472, 1983Link, Google Scholar

17. Dekker FW, Dielemann FE, Kaptein AA, et al: Compliance with pulmonary medication in general practice. European Respiration Journal 6:886–890, 1993Medline, Google Scholar

18. Graber AL, Davidson P, Brown A, et al: Dropout and relapse during diabetes care. Diabetic Care 15:1477–1483, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Horne R, Weinman J: Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 47:555–567, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Horowitz RI: Treatment adherence and risk of death after myocardial infarction. Lancet 336:542–545, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Dunn LB, et al: Antipsychotic medication adherence: is there a difference between typical and atypical agents? American Journal of Psychiatry 159:103–108, 2002Google Scholar

22. Patel NC, Dorson PG, Edwards N, et al: One-year rehospitalization rates of patients discharged on atypical versus conventional antipsychotics. Psychiatric Services 53:891–893, 2002Link, Google Scholar

23. Weiden PJ, Zygmunt A: Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia: I. assessment. Journal of Practical Psychiatry and Behavioral Health 3:106–110, 1997Google Scholar

24. Casper ES, Regan JR: Reasons for admission among six profile subgroups of recidivists of inpatient services. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 38:657–661, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Pristach CA, Smith CM: Medication compliance and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1345–1348, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

26. Donohoe G, Owens N, O'Donell C, et al: Predictors of compliance with neuroleptic medication among inpatients with schizophrenia: a discriminant function analysis. European Psychiatry 16:293–298, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. CGI: Clinical Global Impression, in Manual for the ECDEU Assessment Battery, 2nd rev. Edited by Guy W, Benato R. Bethesda, Md, National Institute of Mental Health, 1970Google Scholar

28. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed, Text Revision. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

29. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA: The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 13:261–276, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1–10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 154(suppl 4):1–63, 1997Google Scholar

32. Statistical Package for IBM-PC. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 1990Google Scholar

33. Fleischhacker WW, Meise U, Günther V, et al: Compliance with antipsychotic drug treatment: influence of side effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement 382:11–15, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

34. Kwon J, Collins A, Christenson B: Medication compliance in patients with schizophrenia taking oral antipsychotics. International Journal of Psychopharmacology 3 (suppl 1):124–125, 2000Google Scholar

35. Buchanan A: A two-year prospective study of treatment compliance in patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 22:787–797, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Bartko G, Maylath E, Herczeg I: Comparative study of schizophrenic patients relapsed on and off medication. Psychiatry Research 22:221–227, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Insight in schizophrenia: its relationship to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:43–47, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. McEvoy JP, Howe AC, Hogarty GE: Differences in the nature of relapse and subsequent inpatient course between medication-compliant and noncompliant schizophrenic patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 172:412–416, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Svarstad BL, Shireman TI, Sweeney JK: Using drug claims data to assess the relationship of medication adherence with hospitalization and costs. Psychiatric Services 52:805–811, 2001Link, Google Scholar

40. Weiden PJ, Dixon L, Frances A, et al: Neuroleptic noncompliance in schizophrenia, in Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology: Vol I. Schizophrenia Research. Edited by Tamminga CA, Schulz SC. New York, Raven, 1991Google Scholar

41. Young JL, Zonana HV, Shepler L: Medication noncompliance in schizophrenia: codification and update. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 14:105–122, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

42. Remington G, Shammi CN, Sethna R, et al: Antipsychotic dosing patterns for schizophrenia in three treatment settings. Psychiatric Services 52:96–98, 2001Link, Google Scholar

43. McEvoy JP, Hogarty GE, Steingard S: Optimal dose of neuroleptic in acute schizophrenia: a controlled study of the neuroleptic threshold and higher haloperidol dose. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:739–745, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Stone CK, Garver DL, Griffith J, et al: Further evidence of a dose-response threshold for haloperidol in psychosis. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1210–1212, 1995Link, Google Scholar

45. Hornung WP, Klingberg S, Feldmann R, et al: Collaboration with drug treatment by patients with and without psychoeducational training: results of a 1-year follow-up. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 97:213–219, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

46. Haynes RB, McKibbon A, Kanani R: Systematic review of randomised trials of interventions to assist patients to follow prescriptions for medications. Lancet 348:383–386, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al: Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:241–247, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Weiden PJ, Olfson M: Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:419–429, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar