Private Health Insurance Coverage for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, 1995 to 1998

Abstract

Four years of data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse were combined to examine the characteristics of underinsurance in a sample of privately insured Americans aged 18 to 64. Among these adults, 38 percent (45 million) reported not having behavioral health coverage or not knowing their coverage. Young adults aged 18 to 25, Hispanics, Asians, adults in the lowest income level, and less educated adults were more likely to be underinsured. Untreated addictive and psychiatric problems are costly to society. Underinsurance among socially disadvantaged subgroups deserves greater attention from researchers and policy makers.

Lack of health insurance coverage represents an important barrier to behavioral health care (substance abuse and mental health services) (1,2). Compared with people who have full private insurance, those who do not have behavioral health benefits but who have some health insurance—the underinsured—were found to be less likely to use behavioral health services, particularly in the specialty sector (1). Other studies have found that people who lacked behavioral health coverage were more likely to drop out of treatment early (3) or to receive treatment that did not follow generally accepted guidelines (4).

Timely national estimates of behavioral health coverage provide critical information to policy makers and to others who are concerned with access to and quality of substance abuse and mental health care. In the study reported here, we used multiple waves of data from a national survey to assess demographic disparities in private insurance coverage for behavioral health care among nonelderly adults.

Methods

The study sample was drawn from public use files of the 1995 to 1998 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) (5). The NHSDA is an annual national survey of the use of licit and illicit substances by Americans aged 12 or older. Each year, a multistage area probability sampling method is used to select civilian, noninstitutionalized samples for the survey. They include residents of households, college dormitories, group homes, homeless shelters, and rooming houses, as well as civilians living on military installations. Each year's independent, cross-sectional sample is considered to represent the experience of Americans aged 12 or older. Between 1995 and 1998, a yearly total of about 18,000 to 25,000 individuals completed a face-to-face interview at their place of residence. Interview response rates ranged from 77 percent to 81 percent.

In the NHSDA, the term "private health insurance" refers to health insurance obtained through an employer or union or by direct payment of premiums to a private health insurance company or a health maintenance organization. Persons who report having private insurance are then asked about their coverage for behavioral health care—treatment for alcohol or drug abuse and mental health difficulties.

Coverage for behavioral health care was dichotomized. Respondents who reported having insurance coverage for substance abuse or mental health care were coded as 1. The term "underinsured" refers to those who report having private health insurance but who do not have any coverage for behavioral health care. A separate binary variable was created to identify privately insured adults who reported not knowing whether they had behavioral health coverage.

We examined age, gender, race or ethnicity, education, population density, and residential region. A categorical variable was created to identify each survey year. Four categories of population density are included in the NHSDA: large metropolitan, small metropolitan, nonmetropolitan urban, and nonmetropolitan rural areas. The NHSDA defines four residential regions: North Central, Northeast, South, and West.

Statistical analyses of data from privately insured adults aged 18 to 64 in 1995-1998 were conducted with use of SUDAAN software (6). To hold constant variations in survey year and sociodemographic characteristics, we conducted separate logistic regression analyses to identify correlates of two variables: reporting substance abuse or mental health coverage and having no knowledge of substance abuse or mental health coverage. Because crude odds ratios from unadjusted logistic regression (available upon request) were generally consistent with adjusted estimates from adjusted models, only adjusted odds ratios are reported. This study was declared exempt from review by RTI International's institutional review board because it used public use data files containing no identifying information.

Results

The proportion of adults aged 18 to 64 who reported having private health insurance at the time of the interview increased significantly, from 73 percent in 1995 to 78 percent in 1998 (χ2=50.10, df=6, p<.001). In the combined sample of all privately insured adults during the four-year period, 51 percent were female, 35 percent were aged 18 to 34, 78 percent were white, and 40 percent had not attended college.

Little yearly variation was observed in private insurance coverage for behavioral health care. In the combined sample for this period, more than half of the respondents reported they had coverage for alcohol abuse services (52 percent) or drug abuse services (52 percent) services. Similarly, a majority had coverage for mental health care (59 percent). Many reported that they did not know their substance abuse benefits (39 percent) or mental health care benefits (32 percent). Altogether, 62 percent reported having coverage for substance abuse or mental health services, and 31 percent did not know the extent of their behavioral health care coverage. Of those with behavioral health benefits, 82 percent reported having coverage for both substance abuse and mental health services.

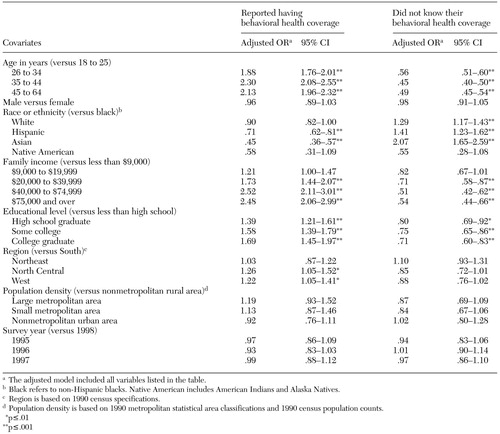

As shown in Table 1, adults aged 18 to 25, respondents of Hispanic and Asian descent, those in the lowest income level, and those without a high school education were most likely to report being underinsured. Residents of the North Central and West regions were slightly more likely than those in the South to have behavioral health coverage.

Young adults aged 18 to 25, respondents in the lowest income level, and respondents without a high school education were most likely to report not knowing their behavioral health coverage. Whites, Hispanics, and Asians were more likely than blacks to report not knowing their behavioral health benefits.

Discussion

Adults in the lowest income level, young adults, Hispanics, Asians, and less educated adults were more likely to report being underinsured. Approximately 45 million privately insured adults aged 18 to 64 reported not having behavioral health coverage or not knowing their coverage. These findings are based on very large probability samples and are new national estimates of self-reported underinsurance and knowledge about behavioral health coverage.

Limitations of this study were its use of data from respondents' self-reports. Some respondents may have had behavioral health benefits but not have known that they did, which would have led to underestimates of the size of this population. The NHSDA design also precludes more detailed analyses of private behavioral health benefits, such as benefit restrictions.

Despite some constraints, these national estimates have important research and policy-making implications. Notably, many privately insured adults do not know their behavioral health benefits. This finding was consistent across the four survey years, suggesting that Americans in general are unaware of their behavioral health coverage or may not understand their health plan's benefits (7).

Lack of knowledge about behavioral health benefits may limit an individual's ability to make informed choices that best fit his or her substance abuse or mental health service needs and the resources available to meet those needs. Future studies should determine whether and how lack of knowledge about behavioral health care benefits represents a barrier to access to and use of behavioral health services (7), particularly among low-income or less educated subgroups. The validity of self-reported insurance coverage also should be investigated.

Having—or not having—insurance coverage for behavioral health care is related to access to such care and to the adequacy of care received (1,2,3,4). Unfortunately, research findings have revealed a huge gap between needed behavioral health care and coverage for such care. Many employment-based health insurance plans cover less than half of the recommended treatment for alcohol-related problems (8). An increasing number of health insurance plans have imposed limits on mental health treatment (9). Between 1988 and 1998, the value of employer-provided mental health care benefits has declined by 55 percent (9).

The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996 prohibits group health plans from imposing more lifetime and annual limits on mental health benefits than on medical care benefits, but it does not require group health plans to provide mental health benefits. Nor does its requirement about benefits apply to substance abuse treatment. Although state and federal health insurance laws strongly affect the benefit levels for substance abuse treatment among insured persons, many states do not have insurance laws that require parity in substance abuse care benefits (8). In fact, data suggest that state laws and employers can make comprehensive behavioral health coverage available and that the cost of upgrading employment-based health insurance is relatively small (8,10).

Many addictive and psychiatric disorders require long-term treatment. Untreated disorders are costly to society. Underinsurance among socially disadvantaged subgroups deserves greater attention from researchers and policy makers.

Acknowledgments

This work was fundedbyresearch grants R03DA013184 and R21DA015938 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant R21AA013255 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Risk Behavior and Mental Health Research at RTI International, 3040 Cornwallis Rd., P.O. Box 12194, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina 27709 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) from multiple logistic regression analyses of privately insured adults aged 18 to 64, 1995-1998 (unweighted N=36,214)

1. Katz SJ, Kessler RC, Frank RG, et al: Mental health care use, morbidity, and socioeconomic status in the United States and Ontario. Inquiry 34:38–49, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

2. Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Sturm R, et al: Alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health care for uninsured and insured adults. Health Services Research 37:1055–1066, 2002Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, et al: Dropping out of mental health treatment: patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 159:845–851, 2002Link, Google Scholar

4. Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC: Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 15:284–292, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Data Archive, National Household Survey on Drug Abuse Series, 2003. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu:8080/samhda-series/00064.xmlGoogle Scholar

6. Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS: SUDAAN Software for the Statistical Analysis of Correlated Data. Research Triangle Park, NC, Research Triangle Institute, 1997Google Scholar

7. Mickus M, Colenda CC, Hogan AJ: Knowledge of mental health benefits and preferences for type of mental health providers among the general public. Psychiatric Services 51:199–202, 2000Link, Google Scholar

8. Goplerud E, Cimons M: Workplace Solutions: Treating Alcohol Problems Through Employment-Based Health Insurance. Washington, DC, George Washington University Medical Center, Ensuring Solutions to Alcohol Problems (ESAP), 2002Google Scholar

9. Health Care Plan Design and Cost Trends:1988 through 1998. Arlington, Va, Hay Group, 2003. Available at www.naphs.org/news/hay99/hay99toc.htmlGoogle Scholar

10. Sing M, Hill S, Smolkin S, et al: Insurance Benefits: The Costs and Effects of Parity for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Insurance Benefits. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar