Predicting Medication Noncompliance After Hospital Discharge Among Patients With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study sought to identify predictors of noncompliance with medication in a cohort of patients with schizophrenia after discharge from acute hospitalization. METHODS: Adult psychiatric inpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder for whom oral antipsychotics were prescribed (N=213) were evaluated at hospital discharge and three months later to assess medication compliance. Comparisons were made between patients who reported stopping their medications for one week or longer and patients who reported more continuous medication use. RESULTS: Of the 213 patients, about a fifth (19.2 percent) met the criterion for noncompliance. Medication noncompliance was significantly associated with an increased risk of rehospitalization, emergency room visits, homelessness, and symptom exacerbation. Compared with the compliant group, the noncompliant group was significantly more likely to have a history of medication noncompliance, substance abuse or dependence, and difficulty recognizing their own symptoms. Patients who became medication noncompliant were significantly less likely to have formed a good therapeutic alliance during hospitalization as measured by inpatient staff reports and were more likely to have family members who refused to become involved in their treatment. CONCLUSIONS: Patients with schizophrenia at high risk for medication noncompliance after acute hospitalization are characterized by a history of medication noncompliance, recent substance use, difficulty recognizing their own symptoms, a weak alliance with inpatient staff, and family who refuse to become involved in inpatient treatment.

The first several weeks after hospital discharge represent a critical period in the course of recovery from exacerbations of chronic schizophrenia. As recuperating but still symptomatic patients make the transition from inpatient to outpatient care, they typically assume greater autonomy and control over several aspects of their daily lives. With this increased independence comes a heightened risk of noncompliance with medication.

A large number of factors have been studied as possible determinants of medication noncompliance among patients with schizophrenia (1). Considerable variation exists in the strength and consistency of evidence supporting these risk factors. In this study, we focus on the role of severity of illness, substance use, insight, treatment alliance, family involvement, and aspects of medication management as possible predictors of medication noncompliance.

Several cross-sectional studies link severity of psychopathology to medication noncompliance (2,3,4,5). Particular attention has been given to grandiosity and paranoia as predisposing patients toward medication noncompliance (2,5). In contrast to the cross-sectional studies, longitudinal research provides a more ambiguous picture. Only one of four longitudinal studies examining this issue found an association between severity of illness at hospital discharge and subsequent medication noncompliance (6,7,8,9).

Strong correlations have been reported between substance use and medication noncompliance among patients with schizophrenia (10,11,12). Intoxication may impair judgment, reduce motivation to pursue long-term goals, and lead to a devaluation of the protection offered by antipsychotic medications. Here as well, however, longitudinal research has not always supported clinical expectations. In a prospective study of nonchronic patients with schizophrenia, a lifetime history of a substance use disorder failed to predict self-reported medication noncompliance (13). Whether patients with schizophrenia with a recent history of substance use disorder are at increased risk of subsequent medication noncompliance remains an important and unsettled issue.

The availability of family members who remind patients to take their medications is widely believed to lower the risk of medication noncompliance. Several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated lower rates of medication noncompliance among patients with schizophrenia who live with family members or with people who supervise their medications (10,14,15). At the same time, patients whose families are ambivalent about antipsychotic medications are at increased risk of medication noncompliance after hospital discharge (16).

Cross-sectional studies have reported that patients who deny being mentally ill have higher rates of medication noncompliance than patients with greater insight into their illness (17,18,19), and improvements in insight have been linked to improved medication compliance (20). However, longitudinal research suggests that the relationship between insight and compliance may not be straightforward. Inpatient assessments of awareness of illness have been found not to predict medication adherence six months (21) or one year (16) after hospital discharge.

Outpatients with schizophrenia who form strong alliances with their therapists seem to be more likely to comply with prescribed medications than patients who form weaker alliances (22). The development of a trusting collaborative clinical relationship may lead patients to perceive practical advantages of continuing with prescribed medications. Inpatients who consent to receive antipsychotic medication have also been found to be more satisfied with and trusting of hospital staff than those who refuse medication (3).

Unpleasant side effects are commonly cited as a primary reason why psychiatric patients refuse to take medications (23,24). However, some researchers have failed to find an association retrospectively (7), cross-sectionally (3), or prospectively (25) between medication side effects and drug refusal or noncompliance. It is unclear whether a history of adverse side effects predicts future medication compliance among patients with schizophrenia.

In the study reported here, medication compliance was assessed in a sample of inpatients with schizophrenia who were interviewed at hospital discharge and then again three months later. This design permitted an examination of whether factors evident during the inpatient stay, such as illness severity, substance use, insight, therapeutic alliance, family support, and medication, predicted medication noncompliance after hospital discharge.

Methods

Data came from the longitudinal patient outcome phase of the Rutgers hospital and community survey, which was conducted between 1993 and 1996. The methods and primary objectives of this study have been described elsewhere (26) and are summarized below.

Eligibility

Eligible subjects were limited to English-speaking, newly admitted psychiatric inpatients, between 18 and 64 years of age, who were enrolled or eligible for Medicaid and had an admitting clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Subjects were entered in the study if they provided written informed consent and met criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) (27) updated to DSM-IV. Patients who had hospital stays longer than 120 days, who were discharged against medical advice, or who were transferred to another inpatient psychiatric facility were excluded.

Subject recruitment and selection

A total of 1,328 consecutively admitted prescreened patients from four New York City general hospitals met the criteria for age, payer status, and clinical diagnosis. Based on medical records and discussions with inpatient staff, we excluded three groups of the screened sample: 4 percent of the screened sample were excluded due to severe general medical conditions, another 4 percent lived outside of New York City, and 9 percent did not speak or understand English.

A total of 1,010 screened patients (76 percent) were eligible for the diagnostic interview. Of this group, 57 percent (N=576) agreed to be interviewed, 31 percent (N=310) refused, and 12 percent were not approached. After the study was thoroughly described to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. Of the 576 patients who consented, 394 (68 percent) met DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Of the 394 patients who met the diagnostic criteria, 71 did not complete the baseline assessment because they left the hospital against medical advice, were transferred to another inpatient facility, had a length of stay greater than 120 days, or withdrew their consent. The baseline inpatient assessment was administered to 323 patients and was completed by 316 patients.

The 316 patients in the study and the 1,010 screened patients not included in the study did not significantly differ in age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, or recent work history. In addition, a similar proportion of the study sample and the excluded patients reported active drug use before admission (42 percent and 38 percent, respectively) and alcohol abuse (38 percent and 39 percent, respectively).

However, blacks were overrepresented in the study sample (58 percent versus 42 percent), and whites and Asians were underrepresented (40 percent and 49 percent for whites, and 2 percent and 9 percent for Asians) (p<.001). Patients in the selected sample were also significantly more likely than those in the nonselected group to report at least one previous psychiatric hospitalization (93 percent and 86 percent; p<.01).

Of the 316 patients who entered the study, 263 (83 percent) were located for a three-month follow-up interview. At the baseline interview, the group lost to follow-up did not significantly differ from the located group in age, sex, race, or score on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (28) or the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (29). Subjects who received depot injections after hospital discharge (N=50) were not included in the study.

Inpatient assessment

Within 72 hours before hospital discharge, patients completed a structured assessment spanning clinical symptoms, substance use disorders, insight into illness, and aspects of their medication management. At that time, structured assessments were also conducted with the clinical staff to assess the therapeutic alliance, family involvement in treatment, and medication management.

Substance use disorders were assessed at hospital admission with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV, with past-six-month criteria (30). Clinical symptoms were assessed at hospital discharge by a research assistant with the BPRS, GAS, and Center for Epidemiological Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D) (31). Insight into illness was assessed with two probes: "Do you believe you have a mental illness?" and "Would you say you have emotional problems?" Positive responses were followed with an item to determine whether the patient believed he or she had schizophrenia: "What do you understand to be your diagnosis?" In addition, an item was included from the National Health Interview Mental Health Supplement (32): "How difficult was it for you to recognize the symptoms of your illness?" Possible responses were very difficult, somewhat difficult, and not difficult.

Patients were also asked about their experience of disturbing medication side effects during the three months before admission. A research assistant who was blind to the results of the structured assessments reviewed each patient's medical record to determine the antipsychotic dosing regimen at hospital discharge. An assessment was also made of medication compliance before hospital admission.

Therapeutic alliance was measured with the six-item Active Engagement Scale (22) completed by inpatient clinicians at the time of discharge. Family involvement was evaluated by asking staff whether patients had any family members, whether family members visited the patient in the hospital, whether they agreed or refused to become involved during the admission, whether they met with staff, and whether they received family therapy.

Follow-up assessment

Three months after hospital discharge, patients were reinterviewed in person with the same instruments to assess change in symptoms, mental health service utilization, and use of antipsychotic medication. At the follow-up interview, patients were asked if they had stopped taking their antipsychotic medications for a period of one week or more during the three months since they were discharged from the hospital. Previous research indicates that whereas most patients (79 percent) with schizophrenia who discontinue medications for less than one week subsequently restart and maintain compliance, a vast majority (91 percent) of those who stop medication for more than one week continue to stay off antipsychotic medications until they relapse (33).

In the analyses described here, patients who acknowledged stopping their medication for one week or more were considered noncompliant with antipsychotics and patients who reported more continuous use were considered compliant.

Analytic strategy and statistical methods

Our primary goal was to assess risk factors for becoming medication noncompliant during the three months after hospital discharge. Patients who were medication noncompliant were first compared with compliant patients on sociodemographic and general treatment characteristics. The two groups were then compared on history of medication noncompliance, clinical symptoms, substance use disorders, awareness of mental illness, therapeutic alliance, family involvement, and medication-related factors.

Using cutoff points developed by Frank and Gunderson (22), we rated patients' therapeutic alliance on the Active Engagement Scale: a rating of less than 14 indicated a good alliance, 14 to 21 a fair alliance, and higher than 21 a poor alliance. Comparisons were also made of symptoms and service utilization patterns of the two groups during the postdischarge period.

Student's t test was used for comparisons involving continuous variables. The chi square test was used for comparisons involving categorical variables, except when the expected cell size fell below 5, in which case the Fisher's exact test was used. Comparisons are considered statistically significant at the 5 percent level (p<.05). A multiple logistic regression, which controlled for patient age, sex, and race, was used to examine the strength of the associations between selected patient characteristics and medication noncompliance. Results are presented as odds ratios and 95 percent confidence intervals. For some variables, the total number of subjects varies due to missing data.

Results

Background characteristics

Of the 213 patients followed up, 41 (19.2 percent) were found to be noncompliant with medication and 172 (80.8 percent) were compliant. No significant group differences were noted in age, sex, race, marital status, education, location before admission, number of previous psychiatric hospitalizations, or legal status at the index admission. The mean±SD ages of the medication noncompliant and compliant groups were 34.8±9.7 years and 37.6±9.6 years, respectively. The majority of patients in both groups were male. Twenty-six males (63.4 percent) were in the noncompliant group, and 103 (59.9 percent) were in the compliant group.

Both groups were racially mixed. In the noncompliant group, 21 patients (51.2 percent) were white, and 20 (48.8 percent) were black. In the compliant group, 71 patients (41.5 percent) were white, 96 (56.1 percent) were black, and four (2.3 percent) were Asian. A majority of the patients in both groups had never married—30 patients (70 percent) in the noncompliant group and 122 (72.4 percent) in the compliant group. Both groups also included a substantial number of patients who had completed fewer than 12 years of education—21 (52.5 percent) in the noncompliant group and 70 (41.7 percent) in the compliant group.

Most of the patients in each group lived in a private house or apartment before the index admission—29 patients (70.8 percent) in the noncompliant group and 108 (62.8 percent) in the compliant group. Most had had three or more previous psychiatric hospitalizations—30 patients (75 percent) and 128 patients (70.3 percent), respectively. Most were involuntarily admitted for the index hospitalization—26 (63.4 percent) and 95 (55.2 percent), respectively.

Patients who became medication noncompliant were significantly more likely than those who remained compliant to have been medication noncompliant during the three-month period before the index hospitalization (35 patients, or 85.4 percent, versus 87 patients, or 51.7 percent; χ2=15.4, df=1, p<.001).

Symptoms at hospital discharge

At hospital discharge, the two study groups did not differ significantly in the mean±SD GAS score (41.4±10.7 for the noncompliant group and 40.8±11.1 for the compliant group), in the CES-D score (22.3±9.8 and 22.8±10.3, respectively), and BPRS score (47.1±11.7 and 45.8±14.1, respectively). In addition, no significant group differences were found in the mean score at discharge on the BPRS grandiosity item (2.7 for noncompliant patients and 2.3 for compliant patients) or the suspiciousness item (2.9 and 2.4, respectively).

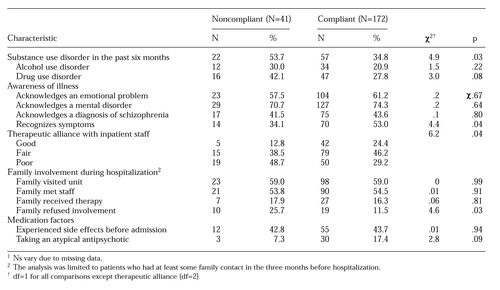

As Table 1 shows, patients who became medication noncompliant were significantly more likely than their compliant counterparts to meet past-six-month criteria for a substance use disorder.

Awareness of illness

As Table 1 indicates, most patients in both groups believed that they had a mental illness or an emotional problem. A smaller proportion further believed that their diagnosis was schizophrenia. A significantly larger proportion of patients who became medication noncompliant reported that they found it somewhat or very difficult to recognize their clinical symptoms.

Therapeutic alliance

Patients who became medication noncompliant were only about half as likely as those who continued on their prescribed medications to have formed a good therapeutic alliance during the hospitalization. Patients who became medication noncompliant received significantly poorer mean scores on four of the six Active Engagement Scale subscales: optimism about the usefulness of treatment (3.1 for noncompliant patients and 2.6 for compliant patients; t=2.8, df=209, p=.006); meaningful involvement in therapy (3.1 and 2.6, respectively; t=2.7, df=209, p=.009); interest in understanding their illness (2.5 and 3, respectively; t=1.2, df=209, p=.015), and realistic perceptions of the therapist (2.5 and 2, respectively; t=2, df=209, p=.044). The two groups did not significantly differ on subscales that measure the extent to which patients share personal information with the therapist (scores of 2.4 and 2.3) or participate in treatment (2.8 and 2.5).

Family involvement

Almost all of the noncompliant patients (97.5 percent) and compliant patients (96.5 percent) reported having had at least some contact with a family member during the three months before the hospitalization. As shown in Table 1, the two groups with recent family contact were equally likely to receive a visit from a family member during the hospitalization. In addition, no significant group differences were noted in the proportion of patients whose families met with staff or participated in family therapy. However, family members of patients who became medication noncompliant were significantly more likely to refuse to get involved in treatment than family members of patients who continued to take their medications.

Medication factors and side effects

A roughly similar proportion of patients in each group reported experiencing disturbing side effects related to antipsychotic medications during the three months before the index hospitalization. At hospital discharge, most patients in each group were treated with conventional antipsychotic medications. However, as shown in Table 1, a nonsignificant trend (p<.09) toward increased compliance was noted among patients who received the newer atypical antipsychotic medications. Patients who remained medication compliant also tended to receive lower mean dosages of antipsychotic medications as measured in chlorpromazine equivalents—680.9±503.9 mg for noncompliant patients and 560.2±389.9 mg for compliant patients—but this tendency was not statistically significant.

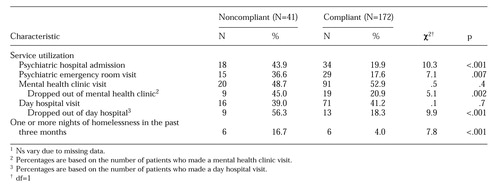

Post discharge outcomes

Table 2 presents data on outcomes at three-month follow-up. Medication noncompliance was associated with poorer outcomes as measured by service utilization patterns, symptoms, and risk of becoming homeless. During the three-month follow-up period, patients who became medication noncompliant were significantly more likely to be admitted to a psychiatric hospital or emergency room. Among patients who attended a psychiatric day hospital or outpatient clinic, medication noncompliance was also associated with increased likelihood of treatment dropout.

Patients who remained on antipsychotic medications experienced a decline in total BPRS score—a mean decrease of 4±12.7 points—indicating symptom improvement. BPRS scores increased among noncompliant patients, a mean increase of 3±12.6 points (t=3, df=192, p=.003). The group who remained compliant also showed a larger increase in mean GAS score—7.7 points for compliant patients and 2.3 for noncompliant patients—but this difference was not statistically significant. Similarly, the medication compliant patients reported a larger mean reduction in depressive symptoms as measured by the CES-D, but this difference was not statistically significant (a decrease of 2.3 for compliant patients and .03 for noncompliant patients).

As Table 2 shows, patients who stopped taking their medications were also significantly more likely to report one or more nights of homelessness during the postdischarge period.

Predicting medication noncompliance

Results of a logistic regression revealed that after adjusting for the patient's age, sex, and race, three variables were independently associated with becoming medication noncompliant: a substance use disorder, a history of medication noncompliance, and family refusal to participate in treatment. The odds ratio, which represents the increased relative risk of medication noncompliance, was 4.6 (CI=1.7 to 12) for substance use disorder, 4.1 (CI=1.3 to 12.2) for history of noncompliance, and 3.4 (CI=1.1 to 10.3) for family refusal to participate in treatment. Problems in identifying clinical symptoms and a poorer total score on the Active Engagement Scale were not significantly related to medication noncompliance in this model, with odds ratios of 1.5 (CI=.6 to 3.8) and 1.1 (CI=1 to 1.2), respectively.

A second regression analysis with similar covariates that substituted the score on the optimism subscale for the total score on the Active Engagement Scale revealed that poorer scores on this subscale were significantly associated with medication noncompliance (OR=1.5, CI=1.1 to 2).

Discussion

We found that approximately one in five patients with schizophrenia reported missing one week or more of oral antipsychotic medications during the first three months after hospital discharge. Missing or stopping antipsychotic medication was strongly associated with several untoward outcomes, including symptom exacerbation, noncompliance with outpatient treatment, homelessness, emergency room visits, and rehospitalization.

Substance use disorders emerged as the strongest predictor of medication noncompliance. This finding confirms and extends those of earlier cross-sectional studies and contrasts with the findings of Kovasznay and coworkers (13), who reported that a lifetime history of a substance use disorder was not associated with medication noncompliance. A recent history of substance abuse or dependence may more accurately predict future medication compliance than a more remote history of a substance use disorder.

A recent history of medication noncompliance was also associated with noncompliance during the transition to outpatient care. As reported in other treatment contexts, past noncompliance proved to be a powerful predictor of future noncompliance (17). Inpatient staff who take a careful history of recent medication noncompliance may improve their prediction of who is at risk for stopping their antipsychotic medications.

The availability of family to help patients has been consistently shown to be associated with improved medication compliance. In the study reported here, little evidence was found that family visits or family therapy sessions during the hospitalization were related to future medication compliance. However, patients whose families refused to participate in treatment were at high risk for stopping their medications. In previous research, a strong correlation has been found between family members' and patients' attitudes toward antipsychotic medications (34). Staff who detect that family members oppose or do not support some aspect of their relative's psychiatric treatment should make a concerted effort to understand and address these family attitudinal barriers.

Patients who were more actively involved in inpatient treatment were more likely to remain on their medications. This finding may help explain the success of psychological strategies that seek to reduce noncompliance by building the patient's motivation to take antipsychotic medications (20,35). Such an approach involves helping patients work through their ambivalence about antipsychotic medications by asking inductive questions, reflecting back responses, providing summary statements, examining the pros and cons of medication compliance, and selectively reinforcing adaptive attitudes.

Awareness of psychotic illness may exist on several levels (36). We found that medication compliance was not related to whether a patient acknowledged having a mental illness or diagnosis of schizophrenia, but rather to the patient's ability to recognize clinical symptoms. Patients who have difficulty recognizing their own symptoms may be less aware of their ongoing need for maintenance treatment and therefore less appreciative of the benefits of antipsychotic medications. It is possible that psychoeducational strategies that help patients develop more accurate subjective health assessments may improve compliance with maintenance antipsychotic treatment.

This study was completed before the widespread use of the newer antipsychotic medications in the United States. It is interesting that patients treated with clozapine or risperidone tended to be less likely to become medication noncompliant, although this relationship was not statistically significant. Possible explanations for this association include the less disturbing side effect profile of the newer antipsychotic medications or their superior clinical effectiveness. A nonsignificant trend was also noted toward increased compliance among patients treated with lower doses of conventional antipsychotic medications.

Various aspects of symptom severity failed to predict medication noncompliance. We expected that grandiosity and suspiciousness, which reduce perceived need for medication and increase perceptions of its harm, would lower medication compliance. However, these symptoms were only weakly related to noncompliance. Progress in this area may require more detailed assessments of how these and other symptoms alter health assessments and perceived risks and benefits of treatment.

The findings are constrained by several important limitations. First, we relied exclusively on patient reports to determine medication compliance. Problems with recall and conscious factual distortions may have introduced inaccuracies in our measurements. Having other informants would have strengthened measurement in this area. Because of the general social undesirability of medication noncompliance, it is likely that the true rate of sustained medication noncompliance was higher than that measured by self-report. Second, only short-term follow-up data were available. A longer follow-up period might have yielded larger numbers of medication noncompliant patients and a different pattern of predictors.

Third, no information was available on postdischarge medication compliance among patients who were lost to follow-up. However, in baseline psychopathology this group resembled the patients who completed the study. Finally, we were unable to determine whether medication noncompliance preceded or followed several of the associated outcomes, such as homelessness, rehospitalization, and treatment dropout.

Conclusions

Inpatients with schizophrenia and comorbid substance use disorders, a history of medication noncompliance, a poor alliance with inpatient staff, difficulty recognizing their own symptoms, and families who refuse to become involved in treatment are all at increased risk of stopping their medications after hospital discharge. Medication noncompliance places patients with schizophrenia at risk of symptom exacerbation, homelessness, and interruptions in the continuity of outpatient care. The availability of promising pharmacologic and psychologic approaches that lower the risk of medication noncompliance should motivate clinicians to identify and provide appropriate preventive interventions to those patients during the critical period of transition from inpatient to outpatient care.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 17998 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and grant MH-43450 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Except for Dr. Weiden, the authors are affiliated with the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Dr. Olfson is also affiliated with the department of psychiatry at the New York State Psychiatric Institute and the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University, 1051 Riverside Drive, New York, New York (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Weiden is with the department of psychiatry at St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center in New York City.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of inpatients with schizophrenia, by whether they were compliant or noncompliant with antipsychotic medication three months after hospital discharge1

|

Table 2. Three-month outcomes of patients with schizophrenia, by whether they were compliant or noncompliant with antipsychotic medication after hospital discharge1

1. Fenton WS, Blyer CR, Heinssen RK: Determinants of medication compliance in schizophrenia: empirical and clinical findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:637-651, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Van Putten T, Crumpton E, Yale C: Drug refusal in schizophrenia and the wish to be crazy. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:1443-1446, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Pan PC, Tantam D: Clinical characteristics, health beliefs, and compliance with maintenance treatment: a comparison between regular and irregular attenders at a depot clinic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 79:564-570, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Kelly FR, Maimon JA, Scott HE: Utility of the health belief model in examining medication compliance among psychiatric outpatients. Social Science and Medicine 25:1205-1211, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pristach CA, Smith CM: Medication compliance and substance abuse among schizophrenic patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1345-1348, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Bartko G, Herczeg I, Zador G: Clinical symptomatology and drug compliance in schizophrenic patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 77:74-76, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Renton CA, Affleck JW, Carstair GM, et al: A follow-up of schizophrenic patients in Edinburgh. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 39:548-600, 1963Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Ayers T, Liberman RP, Wallace CJ: Subjective response to antipsychotic drugs: failure to replicate predictions of outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 4:89-93, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Wilson JD, Enoch MD: Estimation of drug rejection by schizophrenic inpatients with analysis of clinical factors. British Journal of Psychiatry 113:209-211, 1967Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Owen RR, Fischer EP, Booth EM, et al: Medication noncompliance and substance abuse among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 47:853-858, 1996Link, Google Scholar

11. Kashner TM, Rader LE, Rodell DE, et al: Family characteristics, substance abuse, and hospitalization patterns of patients with schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:195-197, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

12. Drake RE, Other FC, Wallace MA: Alcohol use and abuse in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:408-414, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kovasznay B, Fleischer J, Tanenberg-Karant M, et al: Substance use disorder and the early course of illness in schizophrenia and affective psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:195-201, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Razali MS, Yahya H: Compliance with treatment in schizophrenia: a drug intervention program in a developing country. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 91:331-335, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Buchanan A: A two-year prospective study of treatment compliance inpatients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 22:787-797, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Weiden PJ, Dixon L, Frances A, et al: Neuroleptic noncompliance in schizophrenia, in Advances in Neuropsychiatry and Psychopharmacology: Schizophrenia Research, vol 1. Edited by Taminga CA, Schulz SC. New York, Raven, 1991Google Scholar

17. Marder SR, Mebane A, Chien CP, et al: A comparison of patients who refuse and consent to neuroleptic treatment. American Journal of Psychiatry 140:470-472, 1983Link, Google Scholar

18. McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, et al: Insight in schizophrenia: its relation to acute psychopathology. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 177:43-47, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Nageotte C, Sullivan G, Duan N, et al: Medication compliance among the seriously mentally ill in a public mental health system. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 32:49-56, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

20. Kemp R, Kirov G, Everitt B, et al: Randomised controlled trial of compliance therapy. British Journal of Psychiatry 172:413-419, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Cuffel BJ, Alford J, Fischer EP, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and outpatient treatment adherence. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:653-659, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Frank AF, Gunderson JG: The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:228-236, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Ruscher SM, de Wit R, Mazmanian D: Psychiatric patients' attitudes about medication and factors affecting noncompliance. Psychiatric Services 48:82-85, 1997Link, Google Scholar

24. Hoge SK, Appelbaum PS, Lawlor T, et al: A prospective, multicenter study of patients' refusal of antipsychotic medication. Archives of General Psychiatry 47:949-956, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Fleischhacker WW, Meise U, Gunther V, et al: Compliance with antipsychotic drug treatment: influence of side effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 382(suppl):11-15, 1994Google Scholar

26. Boyer CA, Olfson M, Kellermann SL, et al: Studying inpatient treatment practices in schizophrenia: an integrated methodology. Psychiatric Quarterly 66:293-320, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Gibbon M: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R: Patient Education (SCID-P, Version 1.0). Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1990Google Scholar

28. Overall JE, Gorham DP: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports 10:799-807, 1962Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, et al: The Global Assessment Scale. Archives of General Psychiatry 33:766-771, 1976Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 59(suppl 20):22-33, 1998Google Scholar

31. Radloff LS: The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1:385-401, 1977Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Manderscheid, RW, Sonnenschein MA (eds): Mental Health, United States, 1992. DHHS pub (SMA) 92-1942. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1992Google Scholar

33. Weiden PJ, Mott T, Curico N: Recognition and management of neuroleptic noncompliance, in Contemporary Issues in the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Edited by Shriqui C, Nasrallah H. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1995Google Scholar

34. Weiden P, Rapkin B, Mott T, et al: Rating of Medication Influences (ROMI) Scale in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 20:297-310, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

35. Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, et al: Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 312:345-349, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Amador XF, Flaum M, Andreasen NC, et al: Awareness of illness in schizophrenia and schizoaffective and mood disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:826-836, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar