Outcomes of Shelter Use Among Homeless Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine the extent to which the use of case management services predicted public shelter use among homeless persons with serious mental illness after the termination of Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS), a five-year outreach and case management program. METHOD: The sample consisted of 475 Philadelphia ACCESS program participants. Client-level interview data and case manager service delivery records that were collected during the ACCESS intervention period were linked with administrative data on public shelter use for the 12-month period after the ACCESS program was terminated. By using Cox's proportional hazards model, multivariate analyses were conducted to test how the characteristics of the participants and the intensity of case management service use affected the rate of the first entry into a public shelter. RESULTS: Homeless individuals with serious mental illness who were younger, were African American, had fewer years of schooling, and had longer shelter stays during the ACCESS intervention period were more likely to enter shelters in the 12 months after the ACCESS program ended. Although use of vocational and supportive services was associated with a lower probability of shelter entry, use of housing assistance was associated with a higher probability of shelter entry. CONCLUSIONS: The study found that the total number of case management service contacts was not significantly associated with residential outcomes. Rather, the use of specific types of services was important in reducing the use of homeless shelters. These findings suggest that case management efforts should focus on developing vocational and psychosocial rehabilitation services to reduce the risk of recurrent homelessness among persons with serious mental illness.

A number of studies have documented that persons with serious mental illness experience higher rates of residential instability and homelessness than in the general population (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8). While persons with serious mental illness are homeless, they often lose connection with social service systems and therefore face obstacles in maintaining residential stability (1,2,3,4,5,6,7), even when residential and support services are available in the community.

Most homeless persons with serious mental illness are capable of living in the community when they are given appropriate services that meet their multiple needs (9). Despite this encouraging finding, research has documented difficulties in engaging this population in treatment (10,11,12,13).

For the past two decades, numerous programs have attempted to decrease homelessness by linking persons who are homeless and have a mental illness with ongoing mental health services through assertive outreach and case management. These programs have had positive residential outcomes (12,14,15,16,17). The most recent large-scale effort was Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS), an 18-site national demonstration project that lasted from 1993 to 1998 (18,19). An essential program strategy of ACCESS was to enhance access to mainstream mental health services by adopting the assertive community treatment model of intensive case management (20). The distinguishing features of assertive community treatment are assertive outreach and provision of direct and continuous services (20,21). During the ACCESS program a multidisciplinary case management team that included psychiatrists, nurses, and substance abuse and other support specialists contacted clients in nonoffice settings, provided direct intensive support services, and attempted to connect clients with community mental health services. During the intervention period, ACCESS team members shared responsibility for each client. The goal of ACCESS case management was to help homeless people with serious mental illness achieve permanent exits from homelessness.

Previous ACCESS evaluations have focused primarily on the time from program enrollment to the 12-month follow-up interview; these evaluations have found a nearly 40 percent increase in the number of ACCESS participants who lived in independent housing at 12 months after program enrollment (22,23). Little is known, however, about the residential stability of participants after the ACCESS intervention ended.

The study reported here took advantage of a large administrative database on public shelter use to determine long-term residential outcomes of participants after the ACCESS program was terminated, focusing on the ACCESS demonstration sites in Philadelphia. This study examined the extent to which case management services predicted public shelter use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. We hypothesized that more intense use of case management services during the intervention would be associated with lower rates of public shelter use in the 12 months after the ACCESS program ended.

Methods

Sample

Homeless individuals with serious mental illness or a co-occurring substance use disorder who were not currently involved in mental health treatment were eligible for ACCESS (18,19). A total of 800 participants signed informed consent forms and were enrolled in two Philadelphia ACCESS program sites—West Philadelphia and Center City—between May 1994 and June 1998. Of these 800 participants, ten were excluded because they were reported as not having a serious mental illness at the time of referral to the ACCESS case management team, 35 were excluded because they were staying in shelters when the ACCESS program ended, and 215 were excluded because of missing data about case management service use, a key variable of this study. Additionally, 65 participants were excluded because of missing information from the follow-up interview that took place three months after the participant enrolled in the ACCESS program. On the basis of these exclusion criteria, 475 individuals (59 percent) were included in this study. The institutional review boards of the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health approved this study.

Participants who met our study criteria were not significantly different from those who were excluded from the study in their sociodemographic characteristics. However, study participants were less likely than nonparticipants to have a diagnosis of substance abuse disorders (268 participants, or 56 percent, compared with 180 nonparticipants, or 64 percent; χ2=4.78, df=1, p<.05), more likely to use public shelters during participation in ACCESS (168 participants, or 35 percent, compared with 77 nonparticipants, or 28 percent; χ2=4.84, df=1, p<.05), and more likely to be from the Center City site (269 participants, or 57 percent, compared with 103 nonparticipants, or 37 percent; χ2=27.8, df=1, p<.01).

Data sources

This study used three data sources: ACCESS clients' self-reports, case managers' reports, and administrative records of public shelter use. Client-level interview data were collected at the time of referral to case management, at baseline, and at three months after baseline (24) and contained sociodemographic, clinical, and intervention site information. Case managers' records of service delivery were obtained from a weekly log of services that were delivered to clients during the 12 months that they were followed during the ACCESS project. Records of the use of public homeless shelters were obtained from the Philadelphia Office of Emergency Shelter and Services. The shelter data provided dates of admission to and discharge from shelters on a daily basis. We were able to track all adults and families who used publicly funded shelters in Philadelphia by using these data.

Measures

Shelter entry was defined as the first entry into public shelters during the 12-month period following the termination of the ACCESS intervention.

Intensity of case management service use was measured as the total number of contacts with any case management service, as well as the specific types of case management services used that were longer than 15 minutes during the 12 months that clients were followed during the ACCESS project. Six different types of case management service contacts were measured: mental health services, substance abuse services, vocational assistance, entitlement assistance, housing assistance, and other supportive services, such as independent living skills and the development of a peer support network.

Sociodemographic characteristics included age, gender, race, number of years of education, informal social support network, and earlier experience with being homeless. Informal social support network was measured by summing seven items about the frequency of contact with network members—including parents, grandparents, brothers and sisters, a spouse or significant other, children, other family, and friends—during the 60 days before the three-month follow-up interview. The score of each item ranged from 0, indicating no contact, to 6, indicating cohabitation. The total possible score ranged from 0 to 42. Earlier experience with being homeless was measured by two variables that indicated the lifetime number of months homeless and the number of days of shelter use during ACCESS.

Clinical characteristics included the presence of co-occurring psychiatric and substance use disorders and the severity of psychiatric and substance use problems. Severity was measured by using the three subscale scores of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (23,25) at the three-month interview: psychiatric problems, drug use problems, and alcohol use problems. The score of each subscale ranged from 0, indicating no problem, to 1, indicating severe problems. Service need was measured by the number of services that clients reported to need at referral to case management. The number of services ranged from 0 to 5.

To measure site differences, a dummy variable for site was included. Time from baseline to the three-month follow-up interview was also included in the model to control for any effect of variation in the timing of the follow-up interview on clients' shelter use.

Analysis

Multivariate analysis was conducted by using Cox's proportional hazards model to test the study hypothesis that the intensity of use of case management services would predict the likelihood of participants' entering shelters during the 12 months after the ACCESS program ended. The model controlled for the effects of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as well as the intervention site, all of which were associated with residential outcomes in previous studies (16,17,26,27,28).

Cox's proportional hazards model is appropriate for studying the occurrence and timing of events with data that contain censored cases (29). In this study, the event of interest is shelter entry. Individuals who had not entered shelters during the 12-month period after the end of the ACCESS program were considered censored cases. The effect of explanatory variables on the shelter entry rate was examined with risk ratios, the relative risk of shelter entry associated with each independent variable.

Results

Sample characteristics

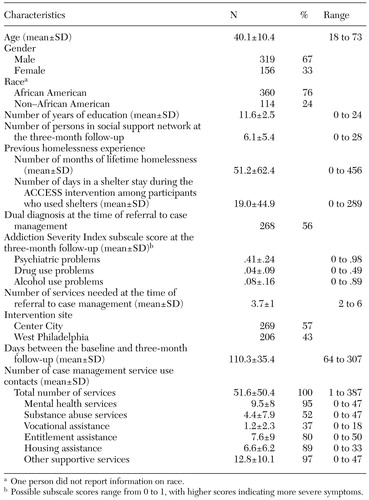

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and the intervention sites of the 475 study participants and the amount and types of case management services that the participants received during ACCESS. The participants had a mean±SD age of 40.1±10.4 years; 67 percent were male, and 76 percent were African American. Participants reported an average of 11.6±2.5 years of schooling. A low level of informal social support was reported, with an average score of 6.1±5.4 at the three-month follow-up interview. The duration of lifetime homelessness ranged from less than one month to 38 years, with an average of 51.2±62.4 months and a median of 29 months. The average duration of a shelter stay during ACCESS was 19±44.9 days.

More than half (56 percent) of the study participants had dual diagnoses. The scores on the ASI psychiatric, drug abuse, and alcohol abuse subscales at the three-month follow-up interview were, respectively, .41±.24, .04±.09, and .08±.16. Study participants reported needing an average of 3.7 out of five services at referral to case management. More than half the study participants (57 percent) were from the Center City intervention site. The time between the baseline and the three-month follow-up interview varied from 64 days to nearly ten months.

The number of service contacts with case managers varied considerably, ranging from one to 387 contacts during the ACCESS intervention period, with an average of 51.6±50.4 contacts and a median of 36 contacts. Study participants varied widely in their use of each service type. Other supportive services ranked highest in the number of case management contacts, with a mean of 12.8±10.1 times. The number of contacts for vocational assistance was lowest with a mean of 1.2±2.3 times.

Multivariate analyses

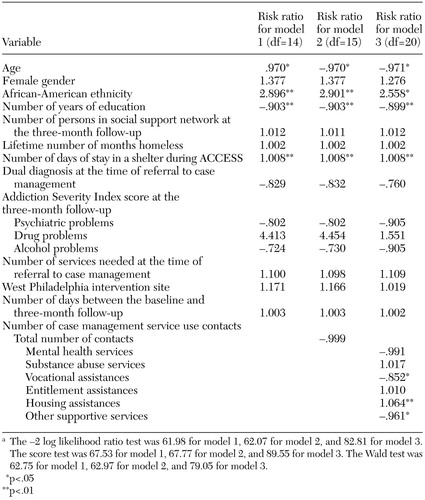

Table 2 presents the results of three hazard models that examine the first shelter entry within the 12-month period after the ACCESS intervention ended. A total of 118 of the 475 participants (25 percent) were admitted to a shelter within this period.

Model 1 showed that age, race, the number of years of education, and the length of stay in a shelter during the ACCESS intervention were significant predictors of shelter entry after the ACCESS program ended. These four variables were significant in model 2 and model 3 as well. Participants were more likely to enter shelters after the ACCESS program ended if they were younger, were African American, had fewer years of schooling, or had longer shelter stays during the ACCESS intervention.

The results of model 2 demonstrated no significant relationship between the total number of service contacts and shelter entry. Model 2 did not improve the model fit over model 1.

In model 3, the six types of case management services were added. Use of three types of case management services significantly predicted the shelter entry rate: vocational assistance, housing assistance, and other supportive services. The addition of these six variables improved the fit over model 1 (-2 log likelihood ratio=20.83, df=6, p<.01). The number of contacts for housing assistance was associated with a 6 percent increase in the risk of shelter entry. The number of contacts for vocational assistance and other supportive services were associated with a decrease in the risk of shelter entry by 15 percent and 4 percent, respectively.

Discussion

The study found that the use of certain types of services—vocational assistance, housing assistance, and other supportive services—was associated with the rate of entry into shelters. However, the total number of case management service contacts was not significantly related to shelter use.

Consistent with the study hypothesis, use of vocational assistance was associated with a significant decrease in the rate of shelter entry. An earlier ACCESS study that examined all 18 study sites suggested that job training and placement assistance was effective in enabling individuals with serious mental illness to become employed, which may prevent homelessness (30). Consistent with the study hypothesis and previous research (16,31), use of supportive services was also significantly associated with a lower probability of shelter entry. This finding provides further evidence that supportive services are critical in maintaining housing stability through the development of daily living skills and a support network with peers.

Contrary to the study hypothesis and previous research (12,16,22,31), use of housing services was associated with increased shelter admissions. There are two possible reasons for this increase. First, housing need may confound the observed association between housing assistance and shelter use. Individuals who receive more housing assistance may have more housing needs and thus may be more likely to become homeless despite receiving housing services from the ACCESS program. Second, conversations with ACCESS project staff indicated that, because of limited residential resources in Philadelphia and the time-consuming administrative procedure for housing placements, case managers sometimes placed clients in shelters to avoid leaving them on the street. Although case management activities in these cases may have actually helped participants gain connection with the service system, the observed effect would be greater shelter use.

Our study had several limitations. First, shelter data do not capture the experiences of homelessness outside the public shelter system. Even though the Philadelphia shelter system captures data on 85 percent of all shelter beds, some study participants may have avoided public shelters and have chosen to live on the street or in unconventional shelters. Second, the data do not represent participants who moved away or were deceased after the end of the ACCESS program. Third, because there was no control group, we cannot conclude whether use of ACCESS case management services is associated with a decrease in shelter use. In addition, because persons who were excluded from the study sample because of missing data on case management service use were more likely to have alcohol- and drug-related disorders and less likely to use shelters during the ACCESS intervention, the study results are of limited generalizability to all ACCESS participants. Moreover, it is important to note that our study did not show a significant association between substance abuse and shelter use, a finding that is contrary to those of several earlier studies, which have reported that the presence of co-occurring disorders was related to housing instability among homeless individuals with serious mental illness (32,33). The lack of association between substance abuse and shelter use may be due to the underrepresentation of individuals with a substance use disorder in our study sample. However, study participants and nonparticipants did not differ in their patterns of the rates of shelter admissions and the duration of shelter stays in the 12 months after the ACCESS program ended (34).

A related concern is the validity of the ASI for assessing behavioral health problems among members of the study sample. Some previous research has shown that the ASI, an instrument designed for studying individuals seeking substance abuse treatment, is a less valid measure when used with homeless persons with mental illness (35). Thus the possible inaccurate estimation of psychiatric and drug and alcohol problems among the study participants may have resulted in lack of significant association between severity of behavioral health problems and shelter use.

Furthermore, the observed relationship between case management contacts for vocational assistance and shelter use may be due to the better functioning of participants who sought vocational assistance services. Although additional analysis indicated that the correlations between the severity of behavioral health problems and the number of vocational service contacts were not significant, the questionable validity of the ASI mentioned above did not allow us to make a firm conclusion about the relationship of vocational assistance to shelter use. Finally, because the study examined only a single urban area and a particular set of case management providers, the generalizability of these results may be limited.

Despite these limitations, our findings have a number of policy and research implications. First, the total amount of case management service use is not necessarily associated with favorable residential outcomes. Rather, specific types of services appear effective in reducing homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychosocial rehabilitation services, including links to peer support and daily living skill training, should be provided for homeless persons with serious mental illness to maintain residential life and housing stability in the community. Vocational services, such as job training and job placement, may also play a significant role in better housing outcomes, even though the effect of vocational services on shelter use requires further investigation.

This study also showed that administrative data can be effectively used to examine public shelter use and residential events beyond the ACCESS intervention period. Linking data from different service systems can help to evaluate interventions across multiple systems over time. Finally, further studies should include information about community resources and use of services other than ACCESS case management service, because those other services may also be associated with public shelter use.

Dr. Min and Dr. Rothbard are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research in the department of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, 3535 Market Street, 3rd Floor, Room 3132, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Wong is with the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of and case management service use by 475 persons during the their participation in Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS)

|

Table 2. Results of the Cox proportional hazards model that estimated the first entry into a shelter within the 12 months after the termination of the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program among 475 study participantsa

a The −2 log likelihood ratio test was 61.98 for model 1, 62.07 for model 2, and 82.81 for model 3.The score test was 67.53 for model 1, 67.77 for model 2, and 89.55 for model 3. The Wald test was 62.75 for model 1, 62.97 for model 2, and 79.05 for model 3.

1. Appleby L, Desai P: Residential instability: a perspective on system imbalance. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 57:515–524, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Bachrach L: Geographic mobility and the homeless mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:27–28, 1987Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Breakey W, Fischer P: Mental illness and the continuum of residential stability. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:147–151, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Caton C, Goldstein J: Housing change of chronic schizophrenic patients: a consequence of the revolving door. Social Science and Medicine 19:759–764, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Chafetz L, Goldfinger S: Residential instability in a psychiatric emergency setting. Psychiatric Quarterly 56:20–34, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Drake R, Wallach M, Hoffman J: Housing instability and homelessness among aftercare patients of an urban state hospital. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:46–51, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Drake R, Wallach M, Teague G, et al: Housing instability and homelessness among rural schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 148:330–336, 1991Link, Google Scholar

8. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256–262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Outcasts on Main Street: A Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. Pub no ADM 92–1904. Washington, DC, Department of Health and Human Services, 1992Google Scholar

10. Asmussen S, Romano J, Beatty P, et al: Old answers for today's problems: helping integrated individuals who are homeless with mental illnesses into exiting community-based programs. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 17:17–34, 1994Google Scholar

11. Tsemberis S, Elfenbein C: A perspective on voluntary and involuntary outreach services for the homeless mentally ill. New Directions for Mental Health Services 82:9–19, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Barrow S, Hellman F, Lovell A, et al: Evaluating outreach services: lessons from a study of five programs. New Directions for Mental Health Services 52:29–45, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Dennis D, Buckner J, Lipton F, et al: A decade of research and services for homeless mentally ill persons: where do we stand? American Psychologist 46:1129–1138, 1991Google Scholar

14. Goering P, Wasylenki D, Lindsay S, et al: Process and outcome in a hostel outreach program for homeless clients with severe mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:607–617, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Kasprow S, Rosenheck R, Frisman L, et al: Referral and housing processes in a long-term supported housing program for homeless veterans. Psychiatric Services 51:1017–1023, 2000Link, Google Scholar

16. McBride T, Calsyn R, Morse G, et al: Duration of homeless spells among severely mentally ill individuals: a survival analysis. Journal of Community Psychology 26:473–490, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

17. Bybee D, Mowbray C, Cohen E: Short versus longer term effectiveness of an outreach program for the homeless mentally ill. American Journal of Community Psychology 22:181–209, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381–386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

19. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Client and site characteristics as barriers to service use by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:387–390, 1997Link, Google Scholar

20. Johnsen M, Samberg L, Calsyn R, et al: Case management models for persons who are homeless and mentally ill: the ACCESS demonstration project. Community Mental Health Journal 35:325–346, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Kuno E, Rothbard A, Sands R: Service components of case management which reduce inpatient care use for persons with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 35:153–167, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless person with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 88:1610–1615, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Rosenheck R, Lam J, Morrissey J, et al: Service systems integration and outcomes for mentally ill homeless persons in the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 53:958–966, 2002Link, Google Scholar

24. Lam J, Rosenheck R: Social support and service use among homeless persons with serious mental illness. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 45:13–28, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. McClellan T, Luborsky L, Woody G, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26–33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Hurlburt M, Wood P, Hough R: Providing independent housing for the homeless mentally ill: a novel approach to evaluating long-term longitudinal housing patterns. Journal of Community Psychology 24:291–310, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

27. Culhane D, Metrzux S, Hadley T: Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate 13:107–163, 2002Crossref, Google Scholar

28. Wong Y, Culhane D, Kuhn, R: Predictors of exit and reentry among family shelter users in New York City. Social Service Review 71:441–462, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

29. Allison PD: Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, North Carolina, SAS Institute Inc., 1995Google Scholar

30. Cook J, Pickett-Schenk S, Grey D, et al: Vocational outcomes among formerly homeless persons with severe mental illness in the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 52:1075–1080, 2001Link, Google Scholar

31. Morse G, Calsyn R, Allen G, et al: Helping homeless mentally ill people: what variables mediate and moderate program effects? American Journal of Community Psychology 22:661–683, 1994Google Scholar

32. Bebout R, Drake R, Xie H, et al: Housing status among formerly homeless dually diagnosed adults. Psychiatric Services 48:936–941, 1997Link, Google Scholar

33. Hurlburt M, Hough R, Wood P: Effects of substance abuse on housing stability of homeless mentally ill persons in supported housing. Psychiatric Services 47:731–736, 1996Link, Google Scholar

34. Min S: Linkage to Services and Public Shelter Utilization Among Homeless Persons With Serious Mental Illness: An Examination of the Role of Case Management. Dissertation. Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania School of Social Work, 2002Google Scholar

35. Goldfinger S, Schutt R, Seidman L, et al: Self-report and observer measures of substance abuse among homeless mentally ill persons in the cross-section and over time. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:667–672, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar