Referral and Housing Processes in a Long-Term Supported Housing Program for Homeless Veterans

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined client characteristics, case management variables, and housing features associated with referral, entry, and short-term success in a Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national intensive case management and rental assistance program for homeless veterans. METHODS: Information collected from homeless veterans at the time of initial outreach contact and from case managers during the housing search was used to create logistic regression models of referral into the program and successful completion of several stages in the process of obtaining stable independent housing. RESULTS: Overall, only 8 percent of the more than 65,000 eligible veterans contacted by outreach workers were referred to the program. Those referred were more likely to be female, to have more sources of income, to have recently used VA services (including residential treatment), and to have serious mental health problems. Once in the program, 64 percent of veterans eventually moved into an apartment, and 84 percent of those who obtained an apartment were stably housed one year later. In general, activities of case managers, such as accompanying the veteran to the public housing authority and securing additional sources of income, were associated with success in the housing process. The therapeutic alliance, clients' housing preferences, and the quality of housing were unrelated to retention of housing. CONCLUSIONS: This supported housing program was judged appropriate for a small percentage of eligible veterans. However, a large proportion of clients were successful in attaining permanent housing, which lends support to the effectiveness of the supported housing approach.

Establishment of stable housing is a key element in the treatment of homeless individuals, particularly those with psychiatric and substance abuse problems. Unfortunately, many homeless individuals exist in an "institutional circuit" of shelters, jails, and psychiatric treatment settings (1).

Recent episodes of violent behavior by homeless mentally ill individuals have intensified concern over this issue. In a widely publicized account of the treatment of a mentally ill homeless man who later committed a murder (2), a psychiatrist who works with homeless persons recently remarked: "Since he was in and out of the shelter system, he'd be a hard person to track down. It sounds simplistic, but in the end it all does come down to housing."

Although the ultimate treatment goal for homeless persons is residence in permanent independent housing, few programs directly provide such housing, and the majority of expenditures for homeless services are for emergency shelter (3). Traditional residential treatment programs and transitional housing programs—the usual "next steps" after emergency shelter stays—have had limited success in establishing clients in permanent housing after completion of treatment (4,5).

Increasingly, supported housing, a combination of ongoing case management and independent community living, has been viewed as a desirable alternative to traditional residential treatment settings for homeless mentally ill individuals (6). Besides being a desirable outcome, stable housing is often needed to facilitate successful participation in mental health and substance abuse treatment (7). The main strengths of the supported housing model are that stable, independent residences are available shortly after entry into the program and that treatment compliance is not a condition of retaining housing (8).

Financial support for housing is an essential ingredient in the implementation of the supported housing model. The Section 8 rental assistance program, sponsored by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), provides housing assistance for more than 3 million individuals (9). One supported housing program showed that Section 8 vouchers could be used successfully in support of housing for homeless mentally ill individuals, given sufficient time and staff support (10). A randomized controlled trial of Section 8 housing assistance and case management techniques for homeless persons demonstrated that receipt of a Section 8 voucher resulted in greater access to independent housing over a two-year period, which was independent of the type of case management received (11).

Results of the Robert Wood Johnson Program for the Chronically Mentally Ill suggest that participation in the Section 8 program increased housing quality and affordability, which in turn was associated with a reduction in the number of days hospitalized and with improved residential stability (12).

None of the studies mentioned have presented information to allow comparison of program entrants to the larger population of potential referrals. In addition, none have examined features of the case management process or housing preferences that are related to housing outcomes. Such information is necessary to understand the applicability of such programs and to improve program outcomes.

In 1991 the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and HUD jointly established the HUD-VA supported housing program to assist homeless veterans who have psychiatric and substance abuse problems. The program is designed to follow the supported housing model. Independent community housing is primarily supported through HUD's Section 8 program, and intensive case management is conducted by VA clinicians. Program clinicians are trained to assist veterans in all aspects of the housing process and to maintain a long-term intensive case management relationship. Thus, by offering housing assistance along with consistent clinical and practical support, the program hopes to provide timely permanent housing for homeless veterans.

This paper describes referral, entry, and progress through the HUD-VA supported housing program. Analyses in this study focused on veterans' characteristics, case management activities, and clients' housing preferences related to program referral and progress through the housing process. The analyses yielded information about the broad applicability of the program to its target population and the extent to which adherence to program design predicts early housing success.

Methods

Program description

The principal elements of the HUD-VA supported housing program are Section 8 rental assistance provided by HUD and intensive case management provided by VA. The Section 8 voucher program provides participants with a rental subsidy, which is administered through the local housing authority. The amount of the subsidy is determined by local fair market rental rates and by each veteran's personal income. The subsidy covers that portion of the fair market rental rate that exceeds 30 percent of the veteran's income.

In principle, rent for veterans with no income can be fully subsidized up to the local fair market rate. However, in practice, housing authorities require some evidence of income support at the time of application to ensure that once beneficiaries are housed, they can maintain themselves. Veterans for whom the fair market rental rate is less than 30 percent of their income receive no subsidy. These terms are generally renegotiated for individual veterans every 12 months. As veterans' incomes increase, eventually they are disqualified for the rental subsidy.

Case managers employed in the HUD-VA supported housing program have complementary roles of housing development and client support. As a housing developer, the case manager maintains an active liaison relationship with the local housing authority, develops listings of appropriate housing, and acts as a community representative to landlords interested in renting to veterans in the program. When clients enter the program, the case manager makes a commitment to providing the long-term support and intensive clinical care required to sustain formerly homeless veterans in apartments.

Program referrals come almost exclusively from VA's national homeless outreach program, the Health Care for Homeless Veterans program (13), through which veterans obtain referrals to a variety of services, including residential treatment from contracted providers. The applications of veterans referred to the program are reviewed by a multidisciplinary admissions committee to evaluate the veterans' appropriateness. Veterans accepted for the HUD-VA supported housing program undergo a comprehensive psychosocial assessment to identify relevant problem areas and to establish specific short- and long-term goals in health status (including mental health), housing, vocational or prevocational activity, and social adjustment. The veteran and case manager use these goals to write an explicit treatment contract. Maintaining housing is not contingent on accepting the contract.

Once the veteran is approved, the case manager submits the veteran's name to the local housing authority, and he or she is assigned one of the designated vouchers. The veteran, with the help of the case manager, then locates and leases a suitable apartment.

Veterans receive case management for the duration of their participation in the program, with the intensity of management determined by clinical need. Monitoring data are collected for up to five years after program entry.

Sample

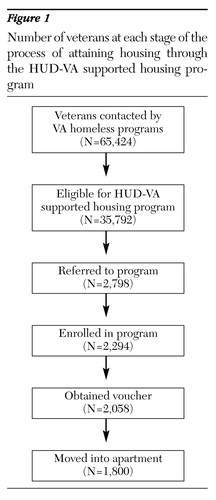

This study analyzed data collected between December 1991 and May 1999 at 35 program sites. During the study period, the Health Care for Homeless Veterans program, the main source of referrals for the HUD-VA supported housing program, conducted assessments for 65,424 veterans at the 35 program sites. Of these, 35,792 (55 percent) met program criteria: they were literally homeless at the time of assessment, had been homeless for one month or more, and had documented mental health or substance abuse problems. Figure 1 shows attrition of the sample at each stage of the housing process.

Measures and data collection

Background characteristics and recent service use. Information on veterans' background characteristics and clinical diagnoses was collected at the time of the initial contact with the Health Care for Homeless Veterans program in a structured intake interview conducted by trained program clinicians, predominantly social workers and nurses. Demographic characteristics included gender, ethnicity, military history, economic situation, and duration of homelessness. The interview also obtained self-reports about substance abuse and psychiatric problems. Veterans were asked about the occurrence of eight psychiatric symptoms. For the analyses, these reports were summed and divided by eight to yield a single score that ranged from 0 to 1. The referring clinician's assessment of psychiatric diagnoses was derived from unstructured assessments using DSM-IV criteria. Self-reported recent use of VA inpatient or outpatient services was also documented during the intake interview.

Use of contracted residential treatment services in the Health Care for Homeless Veterans program in the two months before and two months after intake was documented through analysis of computerized discharge summaries.

Housing processes. On each veteran's referral to the HUD-VA supported housing program, clinicians initiated a flow sheet documenting the client's progress through the housing process. The referring clinician completed items on current housing status and substance abuse and psychiatric diagnoses to confirm the veteran's eligibility for the program. The referring clinician also completed a five-item therapeutic alliance scale based on Horvath and Greenberg's (14) Working Alliance Inventory. The scale included items such as "This veteran and I have a common perception of his or her goals" and "We have established a good understanding of the kinds of changes that would be good for him or her."

The remainder of the flow sheet was completed by the HUD-VA program's case manager and included key dates in the housing process, such as when the veteran was referred to the HUD-VA program, when the treatment plan was signed, and the date of the first visit to the public housing authority. The case manager also documented activities in support of the veteran's entry into housing. For example, case managers helped clients pursue sources of income and accompanied them on appointments with the public housing authority and on visits to prospective apartments.

The case manager also interviewed the veteran before initiating the search for an apartment to gather information about preferences for specific housing features. The features were based on items in instruments used in the evaluation of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation's program for the chronically mentally ill (12). The 18 items covered such features as being near shopping and bus lines and having adequate privacy and a safe neighborhood. Each item was scored 0, not desirable, to 2, very desirable, and the 18 items were summed to form a total score that reflected concerns with housing quality. After the veteran moved into the apartment, the 18-item interview was administered again to assess initial satisfaction with the apartment vis-à-vis the identified desirable features.

Additional measures were constructed indicating whether the apartment included the first, second, and third most important features from the initial list, as well as the total number of desirable features found in the apartment. A scale rating the number and degree of problems in the new apartment, such as cracked or crumbling walls and crime in the neighborhood, was also constructed. Each item was scored 0, not a problem, to 2, a big problem, and the items were summed to form a total score.

Housing outcomes. Housing status was recorded from additional reports of case managers, which were submitted every three months from the time of referral to the program to the time of termination. For the purposes of this study, a positive housing outcome was achieved if a veteran who moved into an apartment was still housed there or in another apartment one year from the date of the move or if the veteran was housed at the time of successful discharge from the program—that is, when the veteran accomplished goals set by the treatment plan.

Data analysis

The purpose of the statistical analyses was to determine the association of veterans' characteristics and program process variables with referral to the HUD-VA supported housing program as well as progress through the housing process. We focused on four stages: referral to the program, attainment of the housing voucher, attainment of an apartment, and retention of housing for one year. Four logistic regression analyses were conducted. In the first, referral to the HUD-VA program was modeled for veterans who were eligible for the program. Next, attainment of the Section 8 housing voucher was modeled for veterans who were referred to the program. The third analysis modeled moving into an apartment for those who obtained a voucher. The fourth analysis modeled retention of housing for one year or at successful discharge for veterans who moved into an apartment.

All the models included covariates for gender, age at the time of the intake interview, and ethnicity. Other variables were included in the model for each dependent variable based on statistical significance of the bivariate association with the dependent variable and in the multivariate model. Backward selection was used to determine retention of a variable in the model. Candidate variables for inclusion were the veterans' characteristics listed in Table 1 as well as the housing process variables described above.

Results

Sample characteristics

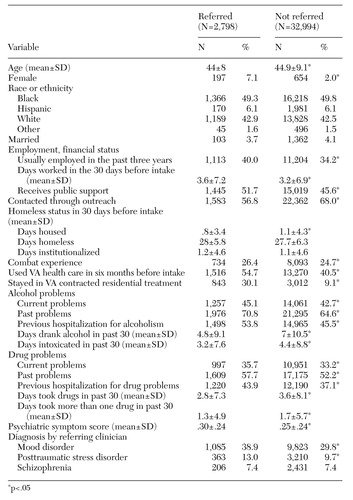

Table 1 presents information on characteristics of veterans referred to the HUD-VA supported housing program and those who were eligible but not referred. Of the 35,792 veterans who were eligible, 2,798 (7.8 percent) were referred to the program. One notable difference between these groups was the higher percentage of women referred to the program.

Serious financial, substance abuse, and psychiatric problems were evident in both the referred group and the group not referred. However, veterans who were referred to the program had slightly higher levels of past and current employment and receipt of public support as well as slightly lower levels of self-reported alcohol and drug use in the month preceding intake. A larger percentage of referred veterans used VA health care services in the six months before intake.

Referral to the program

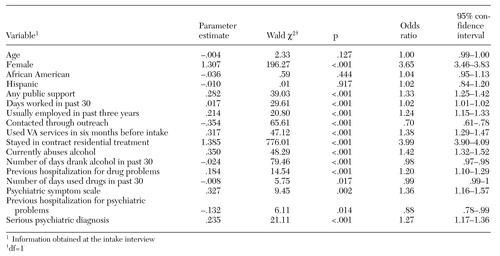

The median time between intake assessment and referral to the program was 100 days; the range was from one day to over one year. Table 2 shows the results of the logistic regression model of referral to the HUD-VA program. The model indicates that referred veterans were more likely to be female. Three variables related to income potential were all positively related to program referral—receipt of public support, days worked in the past 30 days, and usual full- or part-time employment in the three years before intake.

Veterans referred to the program were less likely to be contacted by community outreach than those not referred and were more likely to have used VA services in the six months before intake. By far the strongest predictor of referral was recent admission to VA contracted residential treatment. Self-reported current alcohol problems and past hospitalization for drug problems were both positively related to referral to the program. In contrast, the number of days of drinking alcohol and taking drugs in the 30 days before intake were both negatively related to referral. The psychiatric symptom score and the clinician's diagnosis of serious psychiatric problems were positively related to program referral. Previous hospitalization for psychiatric problems was negatively related to program referral.

Collectively these results suggest that referring clinicians were looking for indicators of appropriateness for the program. They preferentially referred veterans with serious psychiatric or substance abuse problems. They also focused on income potential, a requirement of the housing authority, and beginning signs of recovery from substance abuse.

Attainment of a housing voucher

Of the 2,798 veterans who were referred to the HUD-VA supported housing program, 2,058 (73.6 percent) subsequently obtained a Section 8 rental assistance voucher (see Figure 1). Altogether, 504 referred veterans (18 percent) were not approved by the admissions committee or failed to agree to a treatment plan, and another 236 (8.4 percent) completed these two steps but dropped out before receiving the voucher.

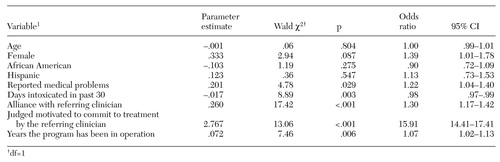

The median time between program entry and attainment of the housing voucher was 38 days. Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression model of attaining a Section 8 voucher. This analysis included only eligible veterans who were referred to the HUD-VA program. Women were more likely than men to attain a voucher. In addition, veterans who reported medical problems at intake were more likely to attain a housing voucher. Those who reported more days drinking to intoxication in the month before intake were less likely to attain a voucher. The referring clinician's judgment of the veteran's readiness to commit to the treatment program and the score on the five-item alliance scale were also highly positively related to attaining a voucher. Finally, the number of years a program had been in operation at the time of a veteran's referral was positively related to success in attaining the housing voucher, which indicated that programs improved with experience.

Attainment of an apartment

Of the 2,058 veterans who obtained a Section 8 voucher, 1,800 (87.5 percent) subsequently selected and moved into an apartment. The median time between obtaining the voucher and moving into an apartment was 37 days.

A logistic regression model of apartment attainment was conducted using both veterans' characteristics at intake and relevant variables reflecting the housing process. No veterans' characteristics were significantly related to apartment attainment. A marginally significant positive association was found for the number of desired housing features listed by the veteran during the housing process (OR=1.03; 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1 to 1.06). In addition, veterans were more likely to attain an apartment if the HUD-VA program case manager accompanied them to the public housing authority on more than one occasion (OR=1.68; 95 percent CI=1.35 to 2.01).

The apartments obtained by HUD-VA program clients seem to have met the veterans' expectations. After moving into the apartment, 84.3 percent of the veterans reported that the apartment had the feature that was most important to them, 84.3 percent said it had their second most important feature, and 84.5 percent said it had their third most important feature. The mean±SD number of features identified as desirable before the apartment search that were found in the apartment was 11.7±2.1. Although the findings are indicative of initial satisfaction with housing, these measures were not predictive of subsequent retention of secure housing.

Retention of secure housing

Housing status of the veterans who moved into Section 8 supported apartments was assessed at one year after attainment of the apartment or at successful discharge from the program, if less than one year. Of the 1,800 veterans who obtained an apartment, 1,649 were eligible for analysis of one-year housing status; one year had not yet elapsed for the remaining 151 veterans. Of the veterans eligible for this analysis, 1,383 (83.9 percent) were housed.

Only one veteran characteristic, gender, predicted one-year housing status. Women were significantly more likely than men to be housed (OR=2.49, CI=1.81 to 3.18). Two case manager activities were related to one-year housing status. Case managers' efforts to secure Supplemental Security Income on the veteran's behalf were positively related to being housed at one year (OR=1.53, CI= 1.14 to 1.92). Interestingly, veterans whose case manager reported accompanying them to the first meeting with the housing authority were less likely to be housed at one year after moving into the initial apartment (OR=.63, CI=.30 to .97). This finding stands in contrast to the positive association between housing attainment and case managers' participation at the initial meeting with the housing authority. As noted above, neither ratings of desirable features possessed by the apartment nor problems with the apartment and neighborhood were predictive of housing retention.

Discussion and conclusions

Homeless veterans with substance abuse or psychiatric problems are a group for whom the establishment of stable housing traditionally has been difficult. The intensive case management and rental assistance program under study here served only approximately 8 percent of the eligible population. Reasons for the low rate of referrals include limited Section 8 voucher availability and the small caseloads and long-term case management that are a part of the program. In addition, referred veterans were much more likely to have recently participated in residential treatment before referral to the supported housing program. Residential treatment is itself a limited resource in VA homeless programs, serving approximately 15 percent of veterans contacted by outreach (13). Therefore, the group of potential referrals may have been reduced markedly by clinicians considering for referral mainly those veterans who completed residential treatment. Participation in residential treatment during the period before intake and referral was also a likely contributor to the relatively long waiting times (approximately 100 days) between intake and referral.

It should also be noted that intensive programs like the HUD-VA supported housing program have a long learning curve. Establishing working relationships with housing authorities, landlords, and treatment providers is a time-consuming task.

Although the program served a relatively small percentage of potential clients, the results showed very satisfactory housing percentages. Approximately 64 percent of veterans referred to the program moved into their own apartment, and more than 84 percent of those who moved into an apartment were still housed one year later or at successful termination from case management. These percentages compare favorably with those in a recent report by Tsemberis (15) of an intensive case management and supported housing program and exceed typical housing percentages in studies of clients discharged from residential treatment (13).

Analyses of veterans' demographic characteristics in relation to the processes of the program yielded few common threads. Women were more likely to be referred, obtain a voucher, and remain in housing. No other demographic characteristic showed a consistent association with successful negotiation of the housing process, partly owing to the analytic strategy used in this study, which created increasingly homogeneous groups.

Several clinical characteristics were associated with referral to the program. In accordance with the mission of the program, veterans who were referred were more likely to have current and past alcohol and psychiatric problems as well as previous hospitalizations for alcohol and drug problems. The number of days of alcohol and drug use in the period just before intake was negatively associated with program referral. Active substance use was likely viewed by referring clinicians as a sign that the veteran was not ready for the program. Most program sites have a mandatory period of sobriety before the housing process can be started. The observed negative relation between success in the program and days intoxicated and attainment of the housing voucher underscores the influence of substance abuse before program entry.

Several findings highlighted the influence of the referring clinician and case manager in the processes of housing attainment and retention. The referring clinician's judgment of the veteran's motivation and therapeutic alliance were the best predictors of attaining a housing voucher. The referring clinicians' judgment of veterans' motivation can potentially be used to predict early progress through the program. In contrast, case managers' involvement in accompanying the veteran to the housing authority during the housing process had different effects at different stages. Such involvement increased the likelihood of moving into an apartment but decreased the likelihood of one-year housing retention. These findings could mean that less capable veterans may obtain apartments with the assistance of a case manager but may later have difficulty sustaining their housing.

We expected that veterans who obtained housing with desired features would have greater satisfaction with housing and would thus be more likely to retain their housing. Consumer choice has been regarded as an important feature of the supported housing model (8). However, scores reflecting clients' ratings of housing features were not significantly correlated in the bivariate analyses with attainment or retention of housing and therefore were not included in final regression models. Clients' scores on the housing features may not have adequately measured their satisfaction with housing. Alternatively, housing features may not be relevant to housing stability. Previous research has shown that clients strongly prefer independent community housing over group residential settings (16). It appears that this dimension overshadows other attributes of the setting.

The study reported here provides a description of processes and short-term outcomes of one relatively large-scale implementation of the supported housing model. We conclude that the intensive case management and long-term support offered by the program serve veterans admitted to the program well, but at a cost of limited population coverage. Subsequent studies will focus on predictors of long-term outcomes of this program and compare the supported housing model with less intensive approaches.

Acknowledgments

The ongoing operation of VA homeless veterans treatment and assistance programs is under the guidance of Lawrence Lehmann, M.D., and Gay Koerber, M.A., of the Department of Veterans Affairs Mental Health Strategic Healthcare Group. Funding for program evaluation also comes from the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors thank Vera Ratliff for assistance with data management.

Dr. Kasprow, Dr. Rosenheck, and Ms. DiLella are affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs, VA Connecticut Healthcare System (182), 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Kasprow, Dr. Rosenheck, and Dr. Frisman are with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Frisman is with the department of psychology at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

Figure 1. Number of veterans at each stage of the process of attaining housing through the HUD-VA supported housing program

|

Table 1. Characteristics of veterans referred to the HUD-VA supported housing program and those not referred

|

Table 2. Logistic regression model of variables predicting referral to the HUD-VA supported housing program among 35,792 eligible veterans

|

Table 3. Logistic regression model of variables predicting Sections 8 housing voucher among 2,798 veterans referred to the HUD-VA supported housing program

1. Hopper K, Jost J, Hay T, et al: Homelessness, severe mental illness, and the institutional circuit. Psychiatric Services 48:659-665, 1997Link, Google Scholar

2. Bernstein N: Frightening echo in tales of two subway attacks. New York Times, June 28, 1999, p A1Google Scholar

3. Toro PA, Warren MG: Homelessness in the United States: policy considerations. Journal of Community Psychology 27:119-136, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Ridgway P, Zipple AM: The paradigm shift in residential services: from the linear continuum to supported housing approaches. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13(4):20-31, 1990Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Leda CA, Gallup P: Program design and clinical operation of two national VA initiatives for homeless mentally ill veterans. New England Journal of Public Policy 8:315-337, 1992Google Scholar

6. Carling PJ: Housing and supports for persons with mental illness: emerging approaches to research and practice. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:439-449, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

7. Lapham SC, Hall M, Skipper BJ: Homelessness and substance abuse among alcohol abusers following participation in Project HART. Journal of Addictive Disease 14:41-55, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Hogan MF, Carling PJ: Normal housing: a key element of a supported housing approach for people with psychiatric disabilities. Community Mental Health Journal 28:215-226, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Office of Policy Development and Research: Reinventing Section 8. Recent Research Results (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, June 1999, pp 1,3Google Scholar

10. Dixon LD, Krauss N, Meyers P, et al: Clinical and treatment correlates of access to Section 8 certificates for homeless mentally ill persons. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:1196-1200, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Hurlburt MS, Wood PA, Hough RL: Providing independent housing for the homeless mentally ill: a novel approach to evaluating long-term longitudinal housing patterns. Journal of Community Psychology 24:291-310, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

12. Newman SJ, Reschovsky JD, Kaneda K, et al: The effects of independent living on persons with chronic mental illness: an assessment of the Section 8 certificate program. Milbank Quarterly 72:171-198, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck R, Chapdelaine JD, et al: Health Care for Homeless Veterans Programs: The 12th Annual Report. West Haven, Conn, VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center, 1999Google Scholar

14. Horvath AO, Greenberg L: Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology 36:223-233, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

15. Tsemberis S: From streets to homes: an innovative approach to supported housing for homeless adults with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Community Psychology 27:225-241, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

16. Schutt RK, Goldfinger SM: Housing preferences and perceptions of health and functioning among homeless mentally ill persons. Psychiatric Services 47:381-386, 1996Link, Google Scholar