Service Systems Integration and Outcomes for Mentally Ill Homeless Persons in the ACCESS Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors evaluated the second of the two core questions around which the ACCESS (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) evaluation was designed: Does better integration of service systems improve the treatment outcomes of homeless persons with severe mental illness? METHODS: The ACCESS program provided technical support and about $250,000 a year for four years to nine sites to implement strategies to promote systems integration. These sites, along with nine comparison sites, also received funds to support outreach and assertive community treatment programs to assist 100 clients a year at each site. Outcome data were obtained at baseline and three and 12 months later from 7,055 clients across four annual cohorts at all sites. RESULTS: Clients at all sites demonstrated improvement in outcome measures. However, the clients at the experimental sites showed no greater improvement on measures of mental health or housing outcomes across the four cohorts than those at the comparison sites. More extensive implementation of systems integration strategies was unrelated to these outcomes. However, clients of sites that became more integrated, regardless of the degree of implementation or whether the sites were experimental sites or comparison sites, had progressively better housing outcomes. CONCLUSIONS: Interventions designed to increase the level of systems integration in the ACCESS demonstration did not result in better client outcomes.

The ACCESS (Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports) program sought to evaluate the effects of efforts to improve the integration of service systems on outcomes for homeless persons who have severe mental illness. The previous article in this issue examined the impact on the service systems themselves of providing funds to support strategies designed to improve systems integration (1). In the study reported in this article we examined the impact of these efforts on client outcomes.

Preliminary analyses of client outcomes from the first two years of the ACCESS program—before the systems integration interventions had been fully implemented—showed that the community in which a client resides is a stronger predictor of service use and outcomes than are individual client characteristics (2,3); that clients treated in communities that have more integrated service systems are more likely to have stable, independent housing arrangements after 12 months (4); that community social capital—the community level of participation in civic life, in political organizations, and in elections—is associated with greater service systems integration and, in turn, with superior housing outcomes (5); and that greater housing affordability predicts superior housing outcomes (5). Thus housing outcomes are affected not only by systems integration but also by features of the wider social environment.

Although these preliminary analyses examined the relationship between client change and systems integration cross-sectionally, they did not evaluate whether specific efforts to change service systems result in better client outcomes.

The central question of the study reported here was not simply whether clients at the experimental sites had superior outcomes to clients at the comparison sites. Service systems are presumed to change slowly, even under the best of circumstances, so we expected that any client benefits resulting from efforts to improve systems integration would be observed gradually. Moreover, we expected that client outcomes would improve at the comparison sites as well at the experimental sites as a result of the assertive community treatment services provided at all sites.

Thus the question was whether improvement in client outcomes across the four cohorts at the experimental sites would be greater than improvement at the comparison sites.

On the basis of the ACCESS program logic model (6), we tested three hypotheses. The first hypothesis was that providing earmarked funds to implement strategies for systems integration would result in greater improvement in client outcomes across the four cohorts at the experimental sites than at the comparison sites. Our second hypothesis was that more complete implementation of a greater number of strategies for improving systems integration would be associated with superior client outcomes. The third hypothesis was that change in the level of systems integration across cohorts, regardless of whether the site was an experimental site or a comparison site and regardless of the degree of implementation of integration strategies, would be associated with parallel improvement in client outcomes. Furthermore, we expected that this relationship would be observed both when integration was measured as the degree of integration across all interorganizational relationships (overall systems integration) and when it was measured across relationships with the primary ACCESS grantee organization (project-centered integration). In evaluating these three hypotheses, we opened up the black box of the ACCESS intervention to assess not only how it worked but also whether it worked.

Methods

As detailed in the article by Randolph and colleagues (6), the ACCESS program provided about $250,000 a year and technical support over four years to nine sites to implement strategies to promote systems integration. These experimental sites, along with nine comparison sites, also received funds to support assertive case management programs to engage and assist 100 clients per site per year. Outcome data were obtained at baseline and three and 12 months later from 7,055 clients across four annual client cohorts at all sites.

Eligibility criteria and data sources

Clients were eligible to receive case management services if they were homeless, suffered from severe mental illness, and were not involved in ongoing community treatment. Operational entry criteria for homelessness and mental illness have been described in detail elsewhere, along with validating data (2). Clients were considered to be homeless if they had lived in an emergency shelter, outdoors, or in a public or abandoned building for seven of the previous 14 days.

Eligible clients were invited by their outreach worker to participate in the case management phase of the ACCESS program. Clients who gave written informed consent were evaluated with a comprehensive interview at baseline and were reinterviewed three and 12 months later. Each site agreed to recruit 100 clients a year into the case management study, and all initiated recruitment over the same three-month period. The first cohort was recruited between May 1994 and July 1995, and the fourth cohort was recruited between May 1997 and July 1998.

Measures I: client characteristics and outcomes

Sociodemographic characteristics, housing, and income. Client characteristics that we documented included age, sex, race, number of days employed, income, receipt of public support payments, duration of the current episode of homelessness, housing status in the 60 days before each interview, and social support—that is, the average number of types of people who would help the client with a loan or transport or in an emotional crisis (2). History of conduct disorder was measured by reports of 11 behaviors occurring before the age of 15, such as being in trouble with the law or school officials, playing hooky, being suspended or expelled from school, and poor academic performance (7). Family instability during childhood was measured with an 11-item scale that addressed experiences before the age of 18, such as parental separation, divorce, death, and poverty (8).

Psychiatric and substance use status. Psychiatric status was assessed with standardized scales that measure self-reported symptoms of depression (9) and psychosis (10) and, at baseline, with interviewer ratings of psychotic behavior. Psychiatric problems, alcohol use, and drug use were further assessed with the composite problem scores from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (11). Diagnoses were based on the working clinical diagnoses of the admitting clinicians on the assertive community treatment teams.

Quality of life. Overall quality of life was evaluated with a summary question, "Overall, how do you feel about your life right now?" Responses to the question were scored on a scale of 1, delighted, to 7, terrible (12).

Primary outcomes. The two primary outcome measures were mental health symptoms and achievement of independent housing. To measure mental health symptoms, a mental health index was created by averaging standardized scores on three mental health outcome measures: the ASI psychiatric composite problem index, the depression scale derived from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (9), and the psychotic symptom scale derived from the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI) (Cronbach's alpha=.75). These scores were constructed by dividing the value of each observation by the baseline standard deviation of each measure. Test-retest reliability of this measure was assessed among 50 clients over a two-week period at one of the study sites and was found to be acceptable (intraclass correlation=.85).

For the purposes of assessing independent housing, participants were considered to be stably housed if they had been living in their own apartment, room, or house—either alone or with someone else—for 30 consecutive days by the measures developed for this study. Test-retest reliability of this measure was also acceptable (kappa=.84).

Service use. Service use was assessed with a series of 23 questions, developed for this study, about use of various types of health and social services during the 60 days before the interview. Another series of questions addressed receipt of public support payments and housing subsidies.

Client-level service integration. In contrast with systems integration, which reflects cooperation among diverse agencies at the macro system level, services integration is a client-level measure that reflects the extent to which individual clients have access to a diverse array of services appropriate to a wide range of potential needs. Dichotomous variables (scored as 0 or 1) were created as indicators of the use of each of six types of services: housing assistance or support from a housing agency, mental health services, substance abuse services, general health care, public income support (at least $100 a month), and vocational rehabilitation services. These measures were summed to form an index of services integration that was equal to the number of domains in which services were received. At baseline, the mean±SD value of this variable was 1.85±1.14 (range, 0 to 6).

We also recorded the proportion of clients who reported having a primary case manager on the basis of a single question that elicited their perception. This proportion was 19.5 percent at baseline, 52 percent at three months, and 53 percent at 12 months.

Measures II: fidelity to the assertive community treatment model

Because variability in the delivery of clinical services could have confounded analysis of the relationship of environmental and service system factors to individual outcomes, case management services provided through the ACCESS program were standardized to conform with the assertive community treatment model (13). Each case management team was evaluated three times during the demonstration with a 27-item rating scale developed by Teague and colleagues (14).

Possible scores on this measure range from 0 to 5, with 5 representing the highest level of fidelity to the assertive community treatment model. The mean score across the 18 ACCESS assertive community treatment teams was 3.42±.19 in year 1, 3.30±.33 in year 2, and 3.36±.29 in year 3, reflecting a relatively high and consistent fidelity to the assertive community treatment model, with little variability across sites and no significant difference between the experimental sites and the comparison sites. Although assertive community treatment in the ACCESS program differed from the usual model in that it was time limited, an 18-month follow-up of a subgroup of ACCESS clients, reported elsewhere (15), showed that the gains were not lost after termination of the program.

Measures III: systems integration strategies and systems integration

Independent variables in the analysis of client outcomes included the degree of implementation of strategies for systems integration and the extent of both overall systems integration and project-centered integration, both of which were described in the previous article (1). Data on the implementation of systems integration strategies were available only from the period during which cohorts 3 and 4 were in treatment, and data on overall systems integration and project-centered integration were available only for cohorts 1, 2, and 4.

Analysis

First we conducted a series of random regression analyses to determine whether there was evidence of client improvement in the outcomes of interest and in access to services over the three client interview points (16). The analysis then proceeded in three phases corresponding to the three hypotheses.

Experimental versus comparison sites. In the first phase of the analysis, changes in outcomes across cohorts were compared between the sites that were randomly assigned to be experimental sites and those that were assigned to be comparison sites. Because clients were not randomly assigned to sites, we expected that there might be baseline differences in client characteristics across study conditions within states. A series of two-way analyses of variance were used to identify baseline characteristics that differentiated clients at the experimental sites and the comparison sites in the entire sample and, more specifically, within each state. These analyses tested main effects for study condition (experimental, 1, versus comparison, 0), main effects for client cohort (coded 1 to 4), and the interaction of cohort and study condition, calculated as the product of these two terms. Baseline measures that showed a significant main effect for study condition or for the interaction between study condition and cohort within at least one state were included as covariates in all subsequent analyses.

To make use of all available outcome data, mixed-effects models were used for the principal analyses of the relationship between treatment condition and changes in outcomes across cohorts (16). To test the hypothesis that there would be progressively greater improvement in outcomes across cohorts at the experimental sites than at the comparison sites, we used a model that used the first cohort as a reference group and evaluated the interaction between study condition and cohort for each of the subsequent cohorts. These models thus included nine key terms: a dichotomous main-effect term representing study condition; three dichotomous main-effect terms representing cohorts 2, 3, and 4; and three interaction terms representing the interaction of study condition and each dichotomous cohort variable.

In addition, a term representing the time of the follow-up interview—three months versus 12 months—was included, along with the potentially confounding baseline covariates described above. This multivariate model evaluated whether differences in improvements in client outcomes between the experimental sites and the comparison sites were significantly greater in later cohorts than in the first cohort.

In these models, each observation represented the measurement of a particular outcome for a particular client at one of the follow-up interviews. Because data from one client could thus be represented up to two times, and because different observations for the same client were likely to be correlated with one another, random effects using compound symmetry covariance structure were modeled for individual clients, thereby adjusting standard errors for the correlated nature of the data. Because client data were nested within sites that were nested within states, we used a three-level hierarchical linear model (17). The software package MLwiN was used for these analyses.

Implementation strategies. A similar analytic approach was used to evaluate the second hypothesis—that more complete implementation of a greater number of strategies for improving systems integration would be associated with superior client outcomes. We assumed that no systems integration strategies attributable to ACCESS had been implemented at the beginning of the demonstration (cohort 1), and scores of zero were recorded for all clients in the first cohort. For clients in cohorts 3 and 4, the value of the implementation measure specific to their site and cohort was used. As noted above, no measures were available for the use of integration strategies from cohort 2, so client data from that cohort were excluded.

The hypothesis was modeled by regressing three- and 12-month outcomes on measures of the implementation of integration strategies at each site, controlling, as in earlier models, for the baseline values of the outcome variables and potentially confounding baseline covariates as well as the term representing interview point.

Changes in systems integration and changes in outcomes. A final set of analyses evaluated whether changes in systems integration between the first client cohort and each subsequent cohort were associated with parallel changes in client outcomes from the first to subsequent cohorts. As noted above, data on systems integration were not available for the third cohort, so client data from that cohort were excluded.

Measures of the amount of change in systems integration across cohorts at each site (from the baseline cohort 1) were generated by subtracting the measure of systems integration corresponding to cohorts 2 and 4 from the measure of systems integration corresponding to cohort 1 at each site. No change in systems integration was observed for cohort 1, so the measure of change in systems integration was zero. Client outcomes for that cohort were thus used as the reference condition for subsequent cohorts.

The hypothesis that client outcomes would improve as systems became more integrated (hypothesis 3) was modeled by regressing three- and 12-month client outcome measures on measures representing change in systems integration from baseline, controlling for the baseline value of the outcome variables, potentially confounding baseline covariates, the interview point (three months or 12 months), and the level of systems integration for the first cohort—that is, the baseline level of systems integration. This last term was included to adjust for the fact that sites regressed to the mean over time—that is, there was a negative correlation between baseline systems integration and the change in systems integration: r=−.39 (p<.05) for the correlation between baseline systems integration and change in integration from cohort 1 to cohort 3 and r=−.36 (p<.05) for the correlation of baseline systems integration and change in integration from cohort 1 to cohort 4.

Two sets of parallel analyses were conducted: one that addressed change in integration for the entire network (overall systems integration) and one that addressed change in the integration of relationships with the agency that was the grantee for the overall ACCESS project (project-centered integration).

Dependent measures and criteria of statistical significance. The analyses are first presented for the primary outcome measures: mental health symptoms and independent housing. Because we had four independent measures of interest—an intention-to-integrate analysis of the experimental group assignment, an analysis of the impact of implementing integration strategies, analyses of changes in integration considering measures of overall integration across all agencies in the network (overall systems integration), and the relationship of these agencies to the primary ACCESS grantee agency (project-centered integration)—a Bonferroni-corrected alpha of .006 (.05 divided by 8) was used as the criterion for statistical significance. Although this is a conservative test of significance, the fact that the sample was large increased the likelihood of significant results at this alpha level.

In addition, these same four analyses were examined for five secondary outcome measures—alcohol abuse, drug abuse, employment, social support, and subjective quality of life—and three service use measures—receipt of public support payments, client-level service integration, and a measure reflecting whether the client indicated that he or she had a primary case manager. Because this involved testing four models on a total of ten outcome measures, resulting in 40 analyses altogether, we used a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of .00125 (.05 divided by 40) to evaluate the statistical significance of these secondary outcomes.

Results

Sample and follow-up rates

A total of 7,229 clients agreed to participate in the follow-up study—an average of about 100 clients per site per year. Complete baseline data were available for 7,055 clients, who constituted the analytic sample. Demographic, clinical, and service use characteristics of clients at the experimental and the comparison sites are summarized below; detailed data are available from the authors. Clients at the experimental sites were worse off than those at the comparison sites at baseline on 15 measures and were better off on only one measure.

The clients at the experimental sites had significantly less education, more family instability during childhood, more antisocial behavior before the age of 15, and less social support, but they felt closer to a greater number of people. They had significantly more days of literal homelessness in the 60 days before program entry, more severe mental health problems, more psychotic behaviors, and more drug problems on the ASI drug problem index. They also expressed a need for a greater number of services and had received fewer services. Because each of these differences was significant within at least one study condition in at least one state, all these variables were included as covariates in the final models.

At least one follow-up interview was conducted with 6,385 clients (90.5 percent); 5,800 (82.2 percent) completed the three-month interview, and 5,471 (77.5 percent) completed the 12-month interview. No significant differences were observed in follow-up rates between the experimental sites and the comparison sites. Logistic regression analysis was used to compare clients who completed at least one follow-up interview and those who did not at both the experimental sites and the comparison sites.

Significant differences at either type of site showed that clients who completed follow-up interviews were more likely to be female (p<.01), to be black (p<.003), to have been incarcerated (p<.02), to have more social support (p<.001), and to use a wider variety of services (p<.001) and less likely to be Hispanic (p<.01). No significant differences were observed in psychiatric symptoms, substance use, housing, or employment between clients who completed the follow-up interviews and those who did not at either type of site.

Client outcomes

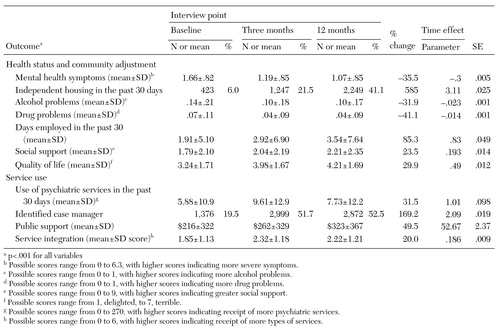

Pooled data on health status, community adjustment, and service use for all cohorts and all sites are listed in Table 1. Substantial improvement from baseline to follow-up was observed on all client outcome measures, although the impact of service delivery could not be distinguished in the observational data from regression to the mean.

Service integration funds and technical assistance

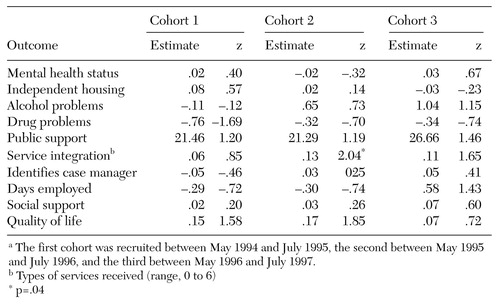

Outcomes of clients at the experimental and comparison sites are compared by cohort in Table 2. No significant differences were observed between the experimental sites and the comparison sites in the amount of change in outcomes on the mental health symptom score from the initial cohort to any of the subsequent cohorts. Similarly, there were no differences between the experimental sites and the comparison sites in clients' likelihood of achieving independent housing from the initial cohort to any of the subsequent cohorts.

Applying the adjusted alpha level of .001, the results were also nonsignificant for alcohol or drug outcomes, three measures of service use, and three measures of community adjustment measures.

Implementation of integration strategies

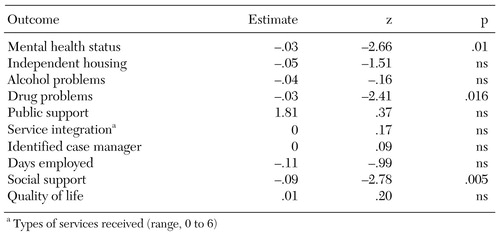

The relationship between client outcomes and implementation of systems integration strategies are summarized in Table 3. Analysis of the relationship between the implementation of systems integration strategies and either of the primary outcomes revealed no significant results at the adjusted alpha level of .001, although trends were observed for reduced mental health symptoms, drug problems, and social support.

Change in systems integration measures

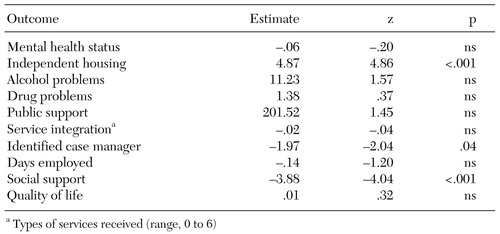

Overall systems integration. The results of the analysis of the association between changes in the overall level of systems integration (all interorganizational relationships) and outcomes—that is, with all relationships between all agencies in these networks taken into account (hypothesis 3)—are summarized in Table 4. Clients in service systems that became more integrated had significantly better housing outcomes, but no benefits were demonstrated on other measures. Curiously, social support declined significantly as systems became more integrated.

Because reduced social support could have been the result of greater use of formal services or the achievement of independent housing, it is notable that improved systems integration was not associated with changes either in improvement in services integration (Table 4) or in receipt of mental health or housing services (data not shown), which is an argument against this explanation. Furthermore, an analysis in which housing outcomes were included as covariates in the model predicting social support clearly demonstrated that the negative association between social support and greater integration was also not attributable to better housing outcomes.

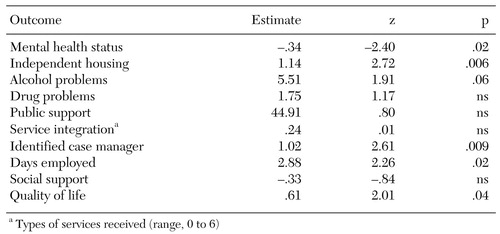

Project-centered integration. The final set of analyses examined the relationship between client outcomes and changes in systems integration, focusing on changes in the relationship of the ACCESS grantee agency to other agencies in the network (the second part of hypothesis 3). The results are summarized in Table 5. These analyses showed that better project-centered integration is also associated with better housing outcomes.

Discussion

Summary of findings

The ACCESS program provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the impact on client outcomes of efforts to increase systems integration: information was available from a relatively large number of sites distributed across the entire United States (N= 18), half the sites received substantial funds for systems integration while half did not, information about the implementation of systems integration strategies and on interorganizational relationships was systematically obtained, assertive community treatment services were standardized across sites, and standardized data on client characteristics and longitudinal outcomes were available from thousands of clients across four annual cohorts.

Our comparisons of outcomes for more than 7,000 clients who were treated at the nine experimental sites and the nine comparison sites provide evidence of greater access to all types of services during the 12 months of treatment throughout the demonstration as well as significant improvement in all client outcome domains. However, we found no evidence that technical support and the allocation of funds for systems integration efforts improved client outcomes beyond their original levels. We also found no evidence of positive mediating effects for the implementation of systems integration strategies over the four years.

As in previous cross-sectional analyses (3,4), we found that as systems became more integrated—that is, as they had more contact and exchange of clients and information—achievement of independent housing was more likely. However, these improvements in housing outcomes were not associated with implementation of strategies designed to improve systems integration. Rather, they were associated with changes in the level of systems integration that appeared to be independent of random assignment and of implementation of systems integration strategies. In addition, the observed association cannot be taken as conclusive evidence of a causal relationship between changing levels of integration and better housing outcomes.

Lack of positive impact

There are several possible explanations for the lack of a positive effect. As shown by the analysis of system change in the ACCESS demonstration (1), although the experimental sites experienced greater mean improvement than the comparison sites in overall systems integration during the demonstration, these differences were small and were statistically significant only in the case of project-centered integration, not overall systems integration.

In addition, full implementation of integration strategies was delayed (1), which shortened the time for these strategies to have an impact on service systems and their clients. In the absence of greater gains in integration at the experimental sites, it is perhaps not surprising that no parallel improvement in client outcomes was observed.

However, as Morrissey and colleagues (1) have pointed out, this negative finding may have resulted partly from the implementation of integration strategies at some of the comparison sites and weak implementation at some of the experimental sites. Because the implementation of systems integration strategies was significantly associated with improvements in systems integration (1), we might have found a relationship between the implementation of systems integration strategies and improvements in client outcomes. Such relationships were not observed.

There are three possible reasons that efforts to improve system integration in the ACCESS demonstration did not result in better client outcomes. First, it is possible that, as observed previously (4), systems integration is unrelated to clinical outcomes other than housing.

Second, it is possible that systems integration is related to clinical outcomes but that the magnitude of the change in systems integration that was attributable to systems integration strategies in the ACCESS program was not sufficient to generate improvement in client outcomes. The fact that changes in systems integration that occurred independently of the intervention were associated with improvements in housing outcomes strengthens previous cross-sectional findings that clients of more integrated service systems have better housing outcomes. However, it is possible that system change generated by ACCESS intervention strategies was simply not sufficient to benefit these clients. A previous analysis of data from the ACCESS program (5) found that systems integration was significantly associated with overall community levels of social capital and with housing outcomes. This finding suggests that the potential effect of interventions to improve integration may be swamped and thereby neutralized by stable characteristics of the broader social environment.

Third, it is possible that in the presence of effective assertive community treatment services, small changes in integration have little impact on most client outcomes. Policy analysts have typically identified both "top down" and "bottom up" strategies for integrating service delivery to clients (18,19). An ethnographic study from one of the ACCESS sites carefully described the ways in which assertive community treatment teams can create "virtually" integrated services for clients regardless of the operation of the service system (20). Thus it is possible that although assertive community treatment teams were established primarily to standardize clinical services across the ACCESS sites, they also ensured that enrollees had help obtaining access to health care and rehabilitation services, which in effect integrates service delivery from the bottom up.

Thus one might wonder whether a stronger relationship between systems integration and clinical outcomes would have been observed if assertive community treatment services had not been provided. However, findings from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program on Chronic Mental Illness (21) suggest that the resulting variability in the quality of clinical service delivery might have further obscured relationships between systems integration and clinical outcomes.

Limitations

This study had several methodological limitations. First, because clients could not be randomly assigned to experimental or comparison sites, we could not perfectly match client characteristics across study conditions. As it turned out, clients at the experimental sites were generally worse off at baseline than clients at the comparison sites. Although we adjusted for these differences, there was still a potential for bias, although the direction of such bias is hard to predict.

Second, because we could not prevent the comparison sites from implementing systems integration strategies, there was some nonadherence to the assigned condition. However, the amount of crossover was small, and the experimental sites as a group showed dramatic differences from the comparison sites in implementing systems integration strategies.

Third, measuring the performance of entire services systems and client outcomes consistently and accurately at diverse sites is a challenging enterprise, and intersite reliability and validity data are not available on measures used in this study. Although data demonstrating the reliability of the systems integration measures we used have been published elsewhere (22) and the reliability and validity of most of the client measures have been established by their originators, differences in the administration of these measures across the 18 sites could have affected our results. In addition, 30 consecutive days of housing may not be an accurate measure of housing stability. Measurement of clinical outcomes can also be challenging in this population. It is possible that some significant differences in outcome were not detected because of measurement imprecision or because data were missing as a result of uncompleted follow-up interviews.

Finally, the results may have been affected by other unmeasured differences between the experimental sites and the comparison sites, such as the availability of mental health or housing services, the skill of case managers, the advent of managed care, and changes in social welfare policy. Although these factors are of theoretical importance, we had no way of measuring them consistently over the study period. Real-world decision makers would face a similar range of unknown, unmeasurable, and uncertain variables in trying to determine whether investing in systems integration efforts would increase benefits for clients in their communities.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the data we have presented are the most comprehensive available to address the relationship between client outcomes and efforts to integrate service systems. The data show that although the level of systems integration is correlated with housing outcomes of homeless people with mental illness, investment in efforts to increase the integration of service systems did not result in better client outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under interagency agreement AM-9512200A between the Center for Mental Health Services and the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs as well as through a contract between the Center for Mental Health Services and ROW Sciences, Inc. (now part of Northrop Grumman Corp.) and subcontracts between ROW Sciences, Inc. and the Cecil A. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of Maryland, and Policy Research Associates of Delmar, New York.

Dr. Rosenheck is affiliated with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center of the Department of Veterans Affairs at West Haven, Connecticut, and with the department of psychiatry of Yale Medical School in New Haven, both of which the late Dr. Lam was affiliated with. Dr. Morrissey is with the Cecil A. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Dr. Calloway is with the departments of psychiatry and pharmacy at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Ms. Stolar is with the Northeast Program Evaluation Center. Dr. Randolph is with the homeless programs branch of the Center for Mental Health Services in Rockville, Maryland. Send correspondence to Dr. Rosenheck at the VA Connecticut Healthcare System (182), 950 Campbell Avenue, West Haven, Connecticut 06516 (e-mail, [email protected]). Coathors of this paper on the ACCESS National Evaluation Team are Margaret Blasinsky M.A., Matthew Johnsen, Ph.D., Henry J. Steadman, Ph.D., Joseph Cocozza, Ph.D., Deborah Dennis, Ph.D., and Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D. This paper is one of four in this issue in which the main results of the ACCESS program are presented and discussed.

|

Table 1. Health status, community adjustment, and service use outcomes for clients at nine experimental sites and nine comparison sites at baseline and after three and 12 months

|

Table 2. Comparison of outcomes of clients at nine experimental sites and nine comparison sites by cohorta

a The first cohort was recruited between May 1994 and July 1995, the second between May 1995 and July 1996, and the third between May 1996 and July 1997.

|

Table 3. Relationships between client outcomes and implementation of systems integration strategies at nine experimental sites and nine comparison sites

|

Table 4. Relationships between changes in client outcomes and changes in overall systems integration at nine experimental sites and nine comparison sites

|

Table 5. Relationships between changes in client outcomes and changes in project-centered integration at nine experimental sites and nine comparison sites

1. Morrissey JP, Calloway MO, Thakur N, et al: Integration of service systems for homeless persons with serious mental illness through the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 53:949-957, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Individual and community-level variation in intensity and diversity of service utilization by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 185:633-638, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck RA, Lam J: Barriers to service use among homeless persons with serious mental illnesses: individual and community-level sources of variation. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

4. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 88:1610-1615, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Services delivery and community: social capital, service systems integration, and outcomes among homeless persons with severe mental illness. Health Service Research 36:691-710, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

6. Randolph F, Goldman HH, Blasinsky M, et al: Overview of the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 53:967-969, 2002Link, Google Scholar

7. Helzer J: Methodological issues in the interpretations of the consequences of extreme situations, in Stressful Life Events and Their Contexts. Edited by Dohrenwend B. New York, Prodist, 1980Google Scholar

8. Kadushin C, Boulanger G, Martin I: Long term reactions: some causes, consequences, and naturally occurring support systems, in Legacies of Vietnam IV. House Committee print no 14, 1981Google Scholar

9. Robins L, Helzer J, Croghan T: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381-389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dohrenwend B: Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI). New York, Columbia University Social Psychiatry Unit, 1982Google Scholar

11. McLellan A, Luborsky L, Woody G: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Lehman A: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

13. Stein L, Test M: Alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Teague G, Bond G, Drake R: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rosenheck RA, Dennis D: Time-limited assertive community treatment (ACT) for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:1073-1080, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Gibbons R, Hedeker D, Waternaux C: Random regression models: a comprehensive approach to the analysis of longitudinal data. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 24:438-443, 1988Medline, Google Scholar

17. Bryk A, Raudenbush S: Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, Calif, Sage, 1992Google Scholar

18. Mechanic D: Strategies for integrating public mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 42:797-801, 1991Abstract, Google Scholar

19. Kagan S: Integrating Services for Children and Families: Understanding the Past to Shape the Future. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993Google Scholar

20. Rowe M: Services for mentally ill homeless persons: street-level integration. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:490-496, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Ridgely M, Morrissey J, Paulson R, et al: Characteristics and activities of case managers in the RWJ Foundation Program on chronic mental illness. Psychiatric Services 47:737-743, 1996Link, Google Scholar

22. Calloway M, Morrissey J, Paulson R: Accuracy and reliability of self-reported data in interorganizational networks. Social Networks 15:377-398, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar