Vocational Outcomes Among Formerly Homeless Persons With Severe Mental Illness in the ACCESS Program

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the vocational outcomes of 4,778 formerly homeless individuals with severe mental illness who were enrolled in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Support (ACCESS) program, a multisite demonstration project designed to provide services to this population. METHODS: Participants were interviewed at the time of enrollment and again three months and 12 months later by trained researchers who were not part of the treatment team to determine their employment status. At 12 months, participants were also asked about the types of services they had received during the past 60 days. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to predict employment at 12 months. RESULTS: ACCESS participants reported receiving relatively few job-related services. Nonetheless, modest but significant increases occurred between baseline and three months and between three months and 12 months in the total proportion of participants who were employed and who were employed full-time and in hourly earnings and estimated monthly earnings. The number of hours worked per week increased significantly between three months and 12 months. When the analysis controlled for site, study condition (whether the ACCESS site received or did not receive extra funds to improve service integration), minority status, addiction treatment, and mental health treatment, participants who were employed at 12 months were more likely to have received job training and job placement services. CONCLUSIONS: Programs that work with homeless mentally ill persons may better serve their clients by placing as great an emphasis on providing employment services as on providing housing and clinical treatment.

The problems that link homelessness and unemployment in America are exacerbated by the fact that many homeless persons who have a severe mental illness do not receive clinical or vocational services (1). Furthermore, national health and disability policies often hamper rather than promote employment among this population (2).

Despite the existence of employment programs for homeless persons with mental illness, such as Comprehensive Opportunities to Assist Consumers Who Are Homeless (COACH), Project HOME, and InCube (3), few studies have focused on vocational outcomes for this population. Existing research consists primarily of studies of vocational rehabilitation among generic populations of homeless persons that may have included subsamples of individuals with severe mental illness.

The Job Training for the Homeless Demonstration Program, a federal program that operated between 1995 and 1998, provided assessment and employability planning; vocational training; job development; and placement, postplacement, and follow-up services to homeless persons (4). In addition, each of the program's 63 sites provided outreach services, case management, housing assistance, substance abuse counseling, mental health treatment, child care services, transportation, and life skills training. Three of the sites provided services exclusively to persons with mental illness, who constituted 3 percent (N=1,232) of the 45,192 program participants. Thirty-three percent of the participants who had a mental illness were placed in jobs, compared with 35 percent of all participants; 60 percent of those with mental illness were employed 13 weeks later, compared with 50 percent of all participants. These results suggest that the employment potential for persons with mental illness is significant.

In an initiative called Next Step: Jobs, which was conducted from 1995 to 1998 by the Corporation for Supported Housing, 20 nonprofit organizations in San Francisco, New York City, and Chicago provided job development, training, placement, and follow-up services to 3,200 supported-housing residents who previously had been homeless (5,6,7). More than a third of the program participants were found to need mental health services, and five of the programs in the initiative served this population exclusively. Results released to date indicate that, over time, equivalent proportions of participants who did and did not have a mental illness became employed. However, participants who had a mental illness were more likely to be working in part-time positions and held fewer jobs overall; furthermore, these participants were more likely to hold jobs within their service delivery program (6).

Findings from studies of both of these programs suggest that job training and placement services may be most effective when they are combined with the additional services that homeless persons need to overcome obstacles to employment. These obstacles include poverty, poor physical health, inadequate housing, low education levels, trauma from victimization, and substance abuse. Service needs are even greater for homeless persons who have a severe mental illness, for they must also cope with debilitating psychiatric symptoms and social stigma (8).

The study reported here assessed the vocational outcomes of participants in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, a federal service demonstration project that operated between 1994 and 1998 and provided coordinated mental health, housing, substance abuse, and social services to homeless persons with severe mental illness.

The ACCESS program examined the effect of service system integration on removing homeless persons with untreated mental illness from homelessness and improving their health status, service use, and quality of life (9,10). Each of the program's 18 sites provided intensive outreach and case management services to 100 clients per year for each of its four years of operation. The sites were located in urban areas in nine states: Connecticut, Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. At each site, one service delivery agency received extra funds to improve service integration (enhancement condition) and one did not (comparison condition).

Outreach services included making initial contact with homeless mentally ill persons in the community—for example, in homeless shelters, on the streets, at soup kitchens, and in drop-in centers—followed by referrals to case management. After an individual was enrolled in the program, case management services were delivered in community settings, with the majority of sites (N=14) using an intensive case management model (11,12). The other four sites used a continuous treatment team (13) or a strengths model (14) to deliver case management services. All of these models provided an array of services that were designed to stabilize symptoms, prevent relapse, and improve functioning in the community.

Rosenheck and Lam (10) analyzed the service needs reported by recipients of ACCESS outreach services. They found that 56 percent of clients identified job assistance—that is, help with job training or finding a job—as an important service need. The ACCESS service mix did not mandate the inclusion of vocational services; however, these services were available at all sites either directly or through referral. Moreover, improved vocational outcomes may have resulted from helping clients meet other needs that were indirectly related to employment.

The ACCESS project provided an opportunity to examine work outcomes and the predictors of those outcomes for a large group of recently homeless individuals during their first year of integrated treatment. Our study addressed three major questions. First, were the participants' vocational outcomes—that is, employment status, full-time employment status, hourly salary, hours worked per week, and estimated monthly earnings—different at baseline, at three months, and at 12 months? Second, what predicted the likelihood that participants would be employed 12 months after they began receiving ACCESS services? And third, how did receipt of vocational and other services—for mental health and substance abuse, for example—affect the likelihood of their being employed at 12 months?

Methods

Procedure

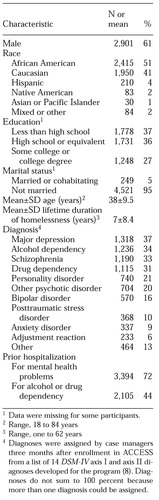

The study evaluated data for 4,778 individuals who were enrolled in the ACCESS program at some time between 1994 and 1998. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study participants at baseline.

Individuals were eligible to enroll in the ACCESS program if they were homeless, had a severe mental illness, and were not receiving ongoing treatment for their illness. To meet eligibility criteria for homelessness, they had to have spent at least seven of the past 14 nights in a shelter, in a public or abandoned building, or outdoors. A 30-item screening instrument (15) was administered by outreach workers to assess mental illness eligibility.

Individuals who met the eligibility criteria were then invited to take part in the evaluation component. Those who consented to participate were interviewed at the time of enrollment (baseline) and again at three months and 12 months after enrollment by trained research interviewers who were not part of the treatment team (8). The face-to-face interviews lasted 60 to 90 minutes each, and participants received a $15 honorarium for each interview. The interview protocol assessed history of homelessness, current housing status, psychiatric history, drug and alcohol use, physical health, employment history, current employment status, service needs and use, demographic characteristics, victimization, legal history, social support, and quality of life.

Measures

Five aspects of employment were measured. Employment status was coded 1 for participants who reported that they had worked one or more days for pay in the 30 days preceding the interview and 0 if they had not. Full-time employment was coded 1 if participants reported working 35 hours or more per week in the 30 days preceding each interview and 0 otherwise. Hours worked per week was recorded as the number of hours a participant reported having been employed during a typical week in the 30 days preceding the interview. Hourly wage was recorded as a participant's average rate of pay per hour in the 30 days preceding the interview. Estimated earned monthly income was calculated by multiplying the number of hours employed per week by the hourly wage and multiplying the resulting product by four.

The service use variables were indicator measures coded 1 for participants who reported receiving any of nine types of services in the 60-day period preceding the interview that took place at 12 months: mental health treatment, substance abuse treatment, job training, job development, educational classes, housing assistance, legal assistance, benefits or entitlements assistance, and crisis intervention.

Baseline demographic data included male gender (coded 1 for men and 0 for women); minority status (coded 1 for African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native American, Asian or Pacific Islander, or mixed race or others, and 0 for Caucasian); college education (coded 1 for any college education and 0 otherwise); and marital status (coded 1 for married or cohabiting and 0 otherwise). Psychiatric diagnoses were DSM-IV axis I or axis II diagnoses reported by the participant's primary case manager.

Analysis

One-sample t tests were used to examine changes in participants' vocational status between baseline and three months and between three months and 12 months. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to examine predictors of the likelihood that participants were employed at 12 months and to determine the impact of receiving vocational services on that likelihood.

Results

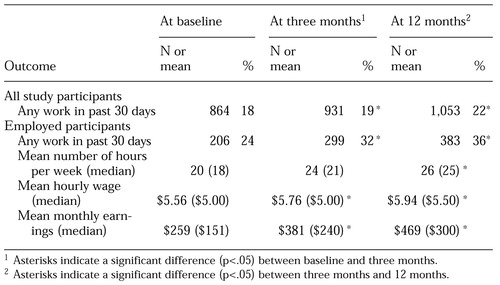

The first question we addressed was whether participants' labor force status improved over the 12-month period. Table 2 presents outcomes by time point, showing that in all cases except one—hours worked per week—employment status improved significantly between baseline and three months and between three months and 12 months. The proportion of participants who had worked at all in the previous 30 days rose slightly, but significantly, from 18 percent at baseline to 19 percent at three months and then to 22 percent at 12 months. Among those who worked, the proportion employed full-time rose significantly. At baseline, only a quarter of employed participants were working full-time; the proportion increased to almost a third at three months and more than a third at 12 months.

The reported mean hourly wage also increased significantly, although median hourly wages were more modest. The average number of hours worked per week also rose slightly over each time interval, but only the difference between three months and 12 months was significant. Estimates of mean monthly earnings rose significantly, from $259 a month to $381 a month to $469 a month, although again median values were considerably lower. Overall, vocational outcomes among the study participants improved gradually and modestly during the first year they received ACCESS program services.

Predictors of employment at 12 months

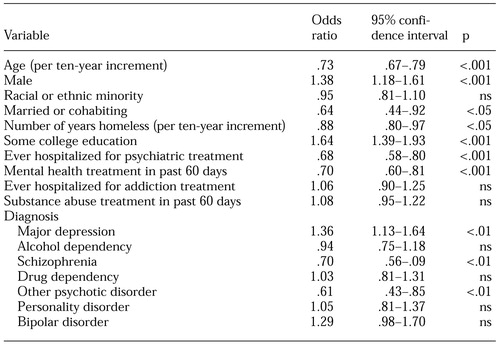

Next, we tested a multivariate model of predictors of employment status at 12 months after enrollment in the ACCESS program. As shown in Table 3, multiple logistic regression analysis controlling for site, study condition (whether the ACCESS site did or did not receive extra funds to improve service integration), minority status, addiction treatment, mental health treatment, and diagnosis found that study participants who were employed at 12 months were more likely to be younger, male, unmarried, and college educated; to have a shorter lifetime history of homelessness, a diagnosis of major depression, and diagnoses other than schizophrenia and psychotic disorders; not to have received mental health treatment in the past 60 days; and never to have been hospitalized for psychiatric treatment.

Services and employment status

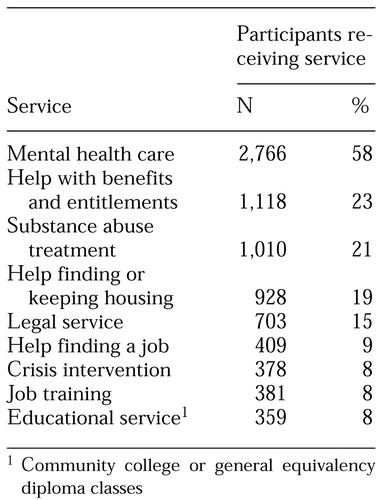

At the 12-month assessment, participants were asked about the services they had received in the past 60 days. The results are summarized in Table 4. Mental health services were by far the most frequently reported—by 2,766 participants (58 percent). Substance abuse services were received by a substantially lower number—1,010 (21 percent). Vocational and educational services were reported by fewer than 10 percent of participants, even though more than three-quarters (78 percent) were not employed at the 12-month assessment, yet more than half (56 percent) had expressed the need for vocational services at baseline.

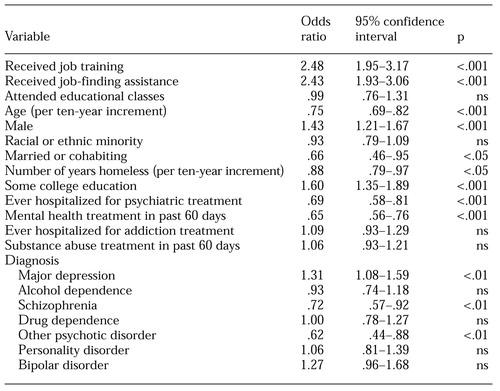

Finally, we investigated whether having received job training, job-finding assistance, or education was associated with employment independently of the other model variables. As shown in Table 5, participants who received job training services and job-finding assistance were about two and one half times as likely to be employed at 12 months than at baseline, all other things being equal. No significant relationship was found between employment and education, and the odds ratios for all other model variables remained essentially unchanged. These results demonstrate an association between vocational services and employment outcomes regardless of severity of mental health impairment, service use, site, study condition, or client characteristics.

Discussion

As they enrolled in the ACCESS program, participants had a significant array of disadvantages, including histories of extensive homelessness, mental illness, and, in many cases, substance use problems. As with other studies of homeless persons with mental illness (1), we found that fairly small proportions of ACCESS program participants received employment and educational services in their first year after enrollment. At the same time, the ACCESS cohort showed steady if modest improvements on most employment indicators, such as employment status, full-time employment status, hourly wages, hours worked per week, and estimated monthly earnings. Our findings highlight the employment potential of these individuals after only one year of coordinated service delivery.

A noteworthy finding was the association between receiving vocational services and being employed at 12 months. The link between services and outcomes remained significant even when the analysis controlled for diagnosis, mental health and substance abuse treatment status, site, study condition, and demographics, and it suggests that formerly homeless people with mental illness may benefit significantly from vocational rehabilitation efforts. At the same time, it points to the need for rehabilitation outreach for this population, given how few of the ACCESS program participants received such services, even though many could have used them. Moreover, the low wages earned by those who were employed indicate that rehabilitation services should be designed to qualify individuals for better-paying jobs that have the potential to raise them out of poverty.

Limitations of this study include its observational nature and the fact that the association between use of vocational services and employment may reflect selection biases. Clients who were more motivated or more work-ready may have been more likely to receive job training and placement assistance, which could have created a spurious association between vocational services and employment. Although we were not able to control for these factors directly—nor for regression to the mean—our controls for education level and willingness to receive substance abuse and mental health treatment suggest that these types of readiness and motivation do not nullify the association between services and outcomes. However, other variables remained uncontrolled in our analysis and may account for this association.

In designing vocational programs for individuals such as those in the ACCESS program, it is important to keep in mind their significant and continuing need for mental health and substance abuse treatment and housing assistance. Special efforts must be made to bring services to this population. Bianco and Shaheen (3) have proposed a "three-legged stool" model of care, in which homeless persons with mental illness receive safe and affordable housing, the supported services that are needed for independent community life—for example, case management, medication, and social skills training—and employment services. They suggest that a comprehensive system of care that focuses on these three elements may enable homeless persons with mental illness to achieve the stability they need to remove themselves from homelessness.

In assisting people with multiple needs, services that have goals other than employment, such as clinical symptom control, receipt of benefits and entitlements, and acceptable housing, may do little to further vocational achievements. Consideration should be given to the adaptation of currently popular models of vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness, such as individual placement and support, the Program of Assertive Community Treatment, the clubhouse model, and other psychosocial rehabilitation models (16). These programs, which have demonstrated improved vocational outcomes (17), may provide homeless consumers of mental health services with the work skills and job supports they need to secure and maintain paid employment.

Conclusions

Employment is an important but often neglected goal of homeless persons with mental illness. Programs that serve this population may best benefit their clients by ensuring that the emphasis placed on employment is equal to that placed on housing and symptom reduction. By receiving vocational services as part of a comprehensive system of care, homeless persons with mental illness may gain access to and use the resources needed to increase economic self-sufficiency and self-determination while rebuilding their lives.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by cooperative agreement UD1SM1368 with the Center for Mental Health Services.

Dr. Cook is director and professor, Dr. Pickett-Schenk is assistant professor, Mr. Grey is project coordinator, and Mr. Banghart is a research data analyst in the mental health services research program of the department of psychiatry at the University of Illinois, 104 South Michigan Avenue, Suite 900, Chicago, Illinois 60603 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rosenheck is director of the Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven, Connecticut, and clinical professor of psychiatry and public health at Yale School of Medicine. Dr. Randolph is acting chief of the homeless programs branch of the Center for Mental Health Services in Rockville, Maryland.

|

Table 1. Characteristics at baseline of 4,778 individuals who participated in the ACCESS program

|

Table 2. Employment outcomes of 4,778 individuals who participated in the ACCESS program

|

Table 3. Results of multiple logistic regression predicting employment at 12-month follow-up, controlling for study site and condition

|

Table 4. Services that study participants reported having received in the 60 days before their 12-month assessment

|

Table 5. Multiple logistic regression model predicting employment at 12 months among participants who received vocational or educational services, controlling for study site and condition

1. Mulkern V, Bradley VJ: Service utilization and service preferences of homeless persons. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 10(2):23-29, 1986Google Scholar

2. Cook JA: Understanding the failure of vocational rehabilitation: what do we need to know and how can we learn it? Journal of Disability Policy Studies 10:127-132, 1999Google Scholar

3. Bianco S, Shaheen G: Employing Homeless Persons With Mental Illness: Principles, Practices, and Possibilities. Sudbury, Mass, Advocates for Human Potential, 1998Google Scholar

4. Trutko JW, Barnow BS, Beck SK, et al: Employment and Training for America's Homeless: Final Report on the Job Training for the Homeless Demonstration Program. Washington, DC, US Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration, Office of Policy and Research, 1997Google Scholar

5. Dressner J, Fleischer W, Sherwood KE: Next Door: A Concept Paper for Place-Based Employment Initiatives. New York, Corporation for Supportive Housing, 1998Google Scholar

6. Rog D, Holupka CS, Brito MC, et al: Next Step: Jobs. Second Evaluation/Documentation Report. Washington, DC, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies, Center for Mental Health Policy, 1998Google Scholar

7. Long DA, Doyle H, Amendolia JM: The Next Step: Jobs Initiative Cost-Effective Analysis: Final Report. New York, Abt Associates Inc. for Corporation for Supported Housing, 1999Google Scholar

8. Fischer PJ, Breakey WR: The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. American Psychologist 46:1115-1128, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Randolph F, Blasinksy M, Leginski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

11. Johnsen M, Samberg L, Calsyn R, et al: Case management models for persons who are homeless and mentally ill: the ACCESS demonstration project. Community Mental Health Journal 35:325-345, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Stein LI, Test MA: An alternative to mental hospital treatment: I. conceptual model, treatment program, and clinical evaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry 37:392-397, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Torrey EF: Continuous treatment teams in the care of the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 37:1243-1247, 1986Abstract, Google Scholar

14. Rapp CA, Chamberlin R: Case management for the chronically mentally ill. Case Management Services 30:417-422, 1985Google Scholar

15. Shern DL, Lovell AM, Tsembris S, et al: The New York City Outreach Project: Serving a Hard-to-Reach Population, in Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

16. Cook JA, Pickett SA: Recent trends in vocational rehabilitation for persons with psychiatric disabilities. American Rehabilitation 20(4):2-12, 1995Google Scholar

17. Cook JA, Razzano L: Vocational rehabilitation for persons with schizophrenia: recent research and implications for practice. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:87-103, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar