Special Section on the GAF: Determinants of Indicated Versus Actual Level of Care in Psychiatric Emergency Services

Abstract

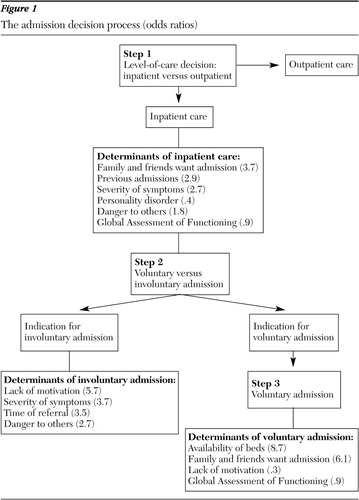

OBJECTIVE: This study was undertaken to improve understanding of the admission decision process by distinguishing between the clinically indicated level of care and actual level-of-care decisions in emergency psychiatry. METHODS: Clinicians in emergency psychiatric services in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, prospectively rated 720 patients by using the Severity of Psychiatric Illness Scale and collected information on demographic, clinical, and contextual parameters. The clinically indicated level of care and actual level-of-care decisions were studied independently, by using multivariate logistic regression analyses. The decision-making process was divided into three consecutive steps: evaluation of clinically indicated inpatient or outpatient level of care (step 1), voluntary or involuntary admission (step 2), and actual admission of patients for whom voluntary admission was indicated (step 3). RESULTS: Each step was determined by separate factors. Specifically, clinically indicated admission (step 1) was associated with family or friends' desire for admission (odds ratio [OR]=3.7), previous admissions (OR=2.9), symptom severity (OR=2.7), and personality disorder (OR=.4). Involuntary admission (step 2) was associated with lack of motivation (OR=5.7), symptom severity (OR=3.7), time of referral (OR=3.5) and danger to self or others (OR=2.7). Actual voluntary admission (step 3) was associated mainly with bed availability (OR=8.7). The overall percentage of correctly predicted cases was 82 percent for all steps in the decision process. CONCLUSIONS: This study showed that each step in the admission decision process is determined by a unique set of variables and provided evidence that contextual factors influence decision making. Guidelines for voluntary admission and civil commitment need to be based on the results of studies that distinguish between the clinical needs of patients and contextual factors.

The primary tasks of psychiatric emergency services are triage, containment, and referral (1), yet evidence-based level-of-care decision guidelines still do not exist (2). The decision to admit a patient has far-reaching medical and economic implications. In most cases clinicians must make the decision rapidly and on the basis of a clinical snapshot (3). For this reason, reliable and valid instruments and guidelines are needed to increase the quality of the admission decision process.

Recently, Blitz and colleagues (4) and George and colleagues (5) reviewed the literature and identified several factors that influence admission decisions, namely community resources, including the availability of beds; patient characteristics; staff characteristics; organizational and situational characteristics; and service utilization review. However, the relative importance of individual factors is unknown. The reviews showed that local organizational factors have a strong impact on the decision to hospitalize a patient and may cause variation in the weighting of factors predicting admission.

Hospital admission is often used as a measure of outcome and quality in research, but it is not really appropriate because the decision to admit a patient is influenced by factors other than the clinical needs of the patient, for example, the availability of beds. Thus a procedure is necessary to help guide the decision process in psychiatric emergency services. One such procedure is to use a stepwise decision model. In this model, clinicians first decide if inpatient or outpatient care is needed and then decide to admit the patient, if appropriate. In this model, the level of care needed is based solely on the clinical needs of the patient and not on contextual factors such as bed availability. We evaluated this stepwise decision model and determined which factors were associated with the clinically indicated level of care versus the actual level of care provided.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted in Greater Rotterdam, in the southwest of the Netherlands. The region is divided into two equally sized and equally urban subregions, each of which is served by a mobile psychiatric emergency service and clinical facilities. Patients are referred to the emergency service by general practitioners, police physicians, or mental health workers. The primary tasks of the emergency service are triage, containment, and referral of psychiatric emergency patients. Patients are examined where they are at the time of referral, for example, at their home, at a police station, or at a community mental health department. In the Netherlands, the police are usually not allowed to take psychiatrically disturbed individuals directly to a psychiatric hospital. The medical examination is carried out by two clinicians—a community psychiatric nurse and a physician. If these clinicians decide that involuntary admission is appropriate, they must submit a request to the local authority, which then officially orders the involuntary admission. The criterion for involuntary admission in the Netherlands is the presence of danger to self or others, not a need for treatment. This criterion includes suicidal behavior and severe social breakdown, for example, manic patients spending money and causing severe interpersonal problems. Patients who are not dangerous to themselves or others but who have psychotic symptoms that need treatment cannot be committed.

A total of 33 clinicians volunteered to participate in the study--15 clinicians from one service and 18 clinicians from the other service--and they accounted for 30 percent of all staff members. They fulfilled 30 percent of day and night shifts, including weekends.

Patients and variables

The patients were aged 18 to 65 years and accounted for approximately 35 percent of all contacts in the psychiatric emergency services during the research period. Because not all staff members participated in our study, we used a convenience sample. Participating clinicians filled out patient record forms for all consecutive patients they saw, which helped minimize selection bias.

Information about demographic variables, including age, sex, and country of birth of the patient and his or her parents, was collected for each patient. Clinical characteristics included previous admissions and severity of problems as assessed by the Severity of Psychiatric Illness Scale (SPI) (3) and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF). The SPI was developed as a client-level decision support tool to assess the need for services, especially inpatient care. The SPI comprises 14 domains, each scored on a 4-point scale from 0 (none) to 3 (severe), with unique behavioral descriptors anchoring each rating. Specific domains include, for example, suicide risk, danger to others, and severity of symptoms (Table 1). The instrument takes about five to ten minutes to complete, and results are expressed in a profile of ratings rather than in a total score. The validity of the instrument has been established in a number of studies (6). Each participating clinician was trained in the use of the SPI, as described in the manual (6), followed by a booster training two months later, to prevent rater drift.

After the SPI training, and as a part of this study, we determined the SPI interrater reliability, which was satisfactory (overall kappa, .76). Five SPI items were selected for the study reported here: suicide risk, danger to others and severity of symptoms in order to replicate earlier studies (3,5); and self-care problems and lack of motivation for treatment because they are criteria for involuntary admission. Diagnoses were made by clinicians on the basis of a clinical interview and were registered in broad categories such as psychotic disorder and depressive disorders. Personality disorders were diagnosed only when sufficient information was available or when patients already had a diagnosis of personality disorder. Whether relatives or friends wanted admission of the patient was also recorded.

Before examining a patient, clinicians indicated whether they knew if a bed was available should they decide to admit the patient. Other contextual characteristics included the subregion of the psychiatric emergency service and whether the time of referral was during working hours or not.

Clinically indicated level-of-care decision process

After examining the patient, the clinicians followed a three-step procedure for the level-of-care decision. Using the 7-point Intensity of Care Scale (ICS), they first determined which level of care was indicated, purely on the basis of the patient's clinical needs. The ICS is used in the Netherlands to determine the level of funding psychiatric institutions receive from the government and insurance companies (7). With this scale, levels of care 0 to 3 can be provided on an outpatient basis, whereas levels 4 through 6 require admission. In the second step, if clinicians decided that inpatient care was required, they then determined whether it would be voluntary or involuntary. All patients who are eligible for involuntary admission are admitted, because psychiatric hospitals in the Netherlands are obliged to admit these patients. In the third step, for patients who met indications for voluntary admission, actual admission depended on, for example, the willingness of the patient to be admitted.

Data collection and analysis

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Mental Health Group Europoort. Because data collection was integrated as part of the regular diagnostic assessment procedure, and because the data were analyzed anonymously, the ethics committee agreed there was no need to attain informed consent. Data were collected from January 2001 to December 2001. There were few missing data (0 to 5 percent), and these were not replaced. Univariate analyses with chi square and t tests were used to examine differences in demographic, clinical, and contextual variables between patients with an indication for an outpatient level of care and those with an indication for an inpatient level of care. These analyses were followed by three logistic regression analyses testing each step in the level-of-care decision process (stepwise analyses). The first step comprised the association between the predictor variables and indicated level of care, outpatient versus inpatient, in the total sample. Step two comprised the association between predictor variables and voluntariness of admission for patients who needed inpatient care. Finally, for patients who were to be admitted on a voluntary basis, determinants of actual admission were studied.

Hierarchical logistic regression analysis was used, and selected patient characteristics were entered first, followed by situational characteristics and community resources. The predictor variables included were previous admissions, five SPI items, GAF score, a diagnosis of psychosis, a diagnosis of personality disorder, whether family or friends wanted admission, bed availability, and time of referral. These variables were added to the model, to replicate earlier findings (4). The SPSS statistical program (8) was used for data analyses. The significance level was set at p<.01.

Results

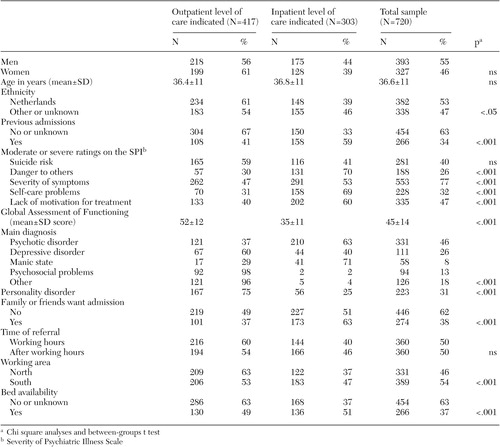

In total 720 consecutive patients entered the study. Table 1 provides data on patients' demographic, clinical, and contextual characteristics. Patients from immigrant groups and patients who had previously been admitted to a hospital more frequently had an indication for inpatient care. Patients for whom inpatient care was indicated had higher scores on most SPI items; however, suicide risk scores were similar regardless of the type of care indicated. Patients for whom inpatient care was indicated were more likely to have more psychotic disorders, manic state, and lower GAF scores. However, personality disorders were not associated with inpatient care. Family or friends' request for admission was associated with an indication for inpatient care. Contextual variables, including bed availability and subregion, were also associated with an indication for inpatient care (Table 2).

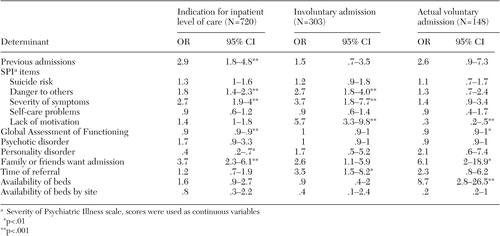

In the multivariate analyses, previous admissions, danger to others, severity of symptoms, GAF score, and whether family or friends wanted admission were positively associated with an indication for inpatient care in the total sample. Personality disorder was negatively associated with an indication for inpatient care. Finally, availability of beds was not associated with an indication for inpatient care. The overall percentage of correctly predicted cases was 83 percent, and Nagelkerke R2 was .65.

Of 303 patients for whom inpatient care was indicated, 155 (51 percent) were eligible for involuntarily admission. Danger to others, severity of symptoms, lack of motivation, and contact after working hours were positively associated with involuntary admission. Other variables were not associated with commitment. The overall percentage of correctly predicted cases was 83 percent, and Nagelkerke R2 was .62.

Finally, of 148 patients for whom voluntary inpatient care was indicated, 89 (60 percent) were actually admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Fifty-nine patients (40 percent) were not admitted: beds were not available (20 patients or 33 percent), patients were unwilling to be admitted (21 patients or 36 percent), and for other reasons (18 patients or 31 percent). Whether family or friends wanted admission and the availability of beds increased the likelihood of actual voluntary admission 6.1 and 8.5 times, respectively. Lack of motivation for treatment decreased the likelihood of actual admission. The percentage of correctly predicted cases was 81 percent, and Nagelkerke R2 was .51. A summary of results is presented in Figure 1.

Discussion and conclusions

We investigated the admission decision process by using a stepwise decision model that distinguished the clinically indicated level of care from actual admission. We found that the indicated level of care was determined mainly by clinical factors, whereas actual admission was also determined by contextual factors such as bed availability or time of referral. These findings may explain the often-contradictory results of admission decision research and highlight the importance of distinguishing the clinical need for admission from actual admission.

Availability of beds was associated with actual voluntary admission but was not associated with clinically indicated inpatient care. Although clinicians do not take bed availability into account when deciding on the level of care indicated for the patient, bed availability becomes important when the patient actually needs to be admitted. In earlier studies, in which indicated level of care and actual admission were not differentiated, mixed results were reported, with some studies finding an association between bed availability and admission (9,10), and others finding no such association (5). This discrepancy illustrates the importance of distinguishing between indicated and actual level of care.

Previous admission was associated with an indication for inpatient care but was not associated with actual admission. Although psychiatric history is important when clinicians determine the level of care needed for a patient, this history is not used to effect actual admission. Personality disorder was also associated with indicated, but not with actual, level of care. A previous study had a similar finding (11), which may be because patients with personality disorder show regressive behavior in restrictive settings such as hospital wards. Clinicians appear to be less inclined to hospitalize a person with other clinical indications for admission in the presence of a personality disorder. However, personality disorder was not associated with actual admission, which may be because the study did not have enough power to detect a significant association; inpatient care was indicated for only a few patients with personality disorders.

The GAF score and whether family or friends wanted admission were both predictors of clinically indicated level of care and actual voluntary admission. Family or friends' desire for admission was the most important determinant of indicated level of care as well as actual admission. If friends or relatives no longer want to or are unable to care for the patient—for example, because of exhaustion—the clinician may opt for hospitalization independently of the patient's clinical condition, judging the family environment unstable and counterproductive to the patient's immediate health (4,12). Level of functioning (GAF score) was also significantly associated with both indicated level of care and actual level of care, showing that the patients who were most in need of hospitalization were actually hospitalized.

Unexpectedly, suicide risk was not associated with either clinically indicated or actual level of care. This finding is in line with one study (5) but contrary to others (3,9,13,14), which may reflect a different approach to suicidal patients in different countries, depending on, for example, the legal consequences if suicide occurs after referral to an outpatient setting. Moreover, the family request for admission may block the suicide effect; it is possible that the families of suicidal patients who do not want their relative to be admitted are able to provide adequate care and supervision at home, making hospital supervision less necessary. These hypotheses should be investigated further. Problems with self-care were also not associated with the level-of-care decision. In our study it is likely that part of the variance in self-care was absorbed by the GAF score, because ability to care for oneself co-determines the GAF score.

Lack of motivation was associated with both involuntary and voluntary admission but in opposite directions. The negative association between motivation and involuntary admission has been reported (15) and possibly reflects the difficulty of treating less motivated patients in an outpatient setting. Less motivated patients are also less willing to be hospitalized voluntarily. Time of referral was associated with involuntary commitment, as has been reported earlier (4). Outpatient mental health services may be more difficult to obtain outside working hours, and clinicians may have no other alternative than requesting involuntary admission. Danger to others was associated with both an indication for inpatient care and involuntary admission (3,4,14,16,17).

This study had several limitations. The study used a convenience sample rather than a representative sample, and therefore, selection bias cannot be ruled out. However, given the random nature of the clinicians' work roster, we have no reason to think that selection bias occurred. In addition, the data we obtained can be used to address the study goal of identifying determinants of psychiatric admission. There may have been an element of self-justification in the way the clinicians scored the SPI and their indications for admission, but this would not have affectedtheir decision concerning the level of care required or the actual care. Finally, although we studied clinician-based and system-based admission decisions separately, our clinicians do not provide a gold standard for admission decisions. More studies of clinical decision making, without contamination by contextual factors, will provide information about clinical and local differences in the admission decision process. Differentiating between clinical and contextual factors is very important, given the local differences in mental health care systems between countries, such as the Netherlands and the United States.

In conclusion, this is the first study taking into account clinically indicated level of care as an outcome variable in the admission decision-making process. By studying separate steps in the admission decision process, we found that each step was determined by a unique set of variables. With this stepwise approach, health care providers can determine whether contextual factors have been successfully dealt with in a large system of care, information that can be used to document quality improvement. Using the clinically indicated level of care as an outcome measure increases the clinical relevance of services research and improves the comparability of study results across different sites, while providing insight into clinical decision making. Guidelines for voluntary admission and civil commitment need to be based on the results of studies that distinguish between the clinical needs of patients and contextual factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Mental Health Group Europoort for financial support and the emergency psychiatric clinicians of Riagg Rijnmond Zuid, Riagg Rijnmond Noord West, and the BAVO/RNO Group for their participation in the study.

Dr. Mulder is affiliated with the Mental Health Group Europoort in Barendrecht, the Netherlands, and with the department of psychiatry of Erasmus MC University Medical Center, Rotterdam. Dr. Koopmans is with the department of health policy and management at the University Medical Center Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Dr. Lyons is with the Northwestern University Medical School in Chicago. Send correspondence to Dr. Mulder at Mental Health Group Europoort, P.O. Box 245, 2990 AE, Barendrecht, the Netherlands (e-mail, [email protected]). This article is part of a special section on the Global Assessment of Functioning scale.

Figure 1. The admission decision process (odds ratios)

|

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of emergency psychiatric patients, according to indicated level of care

|

Table 2. Stepwise multivariate logistic regression analyses of risk factors associated with indicated level of care in the total sample, involuntary admission in the subsample with an indication for inpatient care, and actual admission in the subsample with an indication for inpatient care

1. Gerson S, Bassuk E. Psychiatric emergencies: an overview. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:1–11, 1980Link, Google Scholar

2. Allen MH, Forster P, Zealberg J, et al. Report and recommendations regarding psychiatric emergency and crisis services. A review and model program descriptions. APA Task Force on Psychiatric Emergency Services, 2002Google Scholar

3. Lyons JS, Stutesman J, Neme J, et al. Predicting psychiatric emergency admissions and hospital outcome. Medical Care 35:792–800, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Blitz CL, Solomon PL, Feinberg M. Establishing a new research agenda for studying psychiatric emergency room treatment decisions. Mental Health Services Research 3:25–34, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. George L, Durbin J, Sheldon T, et al. Patient and contextual factors related to the decision to hospitalize patients from emergency psychiatric services. Psychiatric Services 53:1586–1591, 2002Link, Google Scholar

6. Lyons JS. The Severity and Acuity of Psychiatric Illness Scales. An Outcomes Management and Decision Support System. Adult Version. Manual. San Antonio, Harcourt Brace & Company, 1998Google Scholar

7. Schuring G, Liem LE, Roosenschoon BJ. Behandelmodulen: Deel I: [Treatment Modules-Part I. Manual] Utrecht, National Hospital Institute, the Netherlands, 1984Google Scholar

8. SPSS 10 for windows 1995, 1998 and NT UK. Chicago, SPSS, Inc, 2000Google Scholar

9. Engleman NB, Jobes DA, Berman AL, et al. Clinicians' decision making about involuntary commitment. Psychiatric Services 49:941–945, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. Mattioni T, Di Lallo D, Roberti R, et al. Determinants of psychiatric inpatient admission to general hospital psychiatric wards: an epidemiological study in a region of central Italy. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 34:425–431, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Breslow R, Klinger B, Erickson B. Crisis hospitalization on a psychiatric emergency service. General Hospital Psychiatry 15:307–315, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Hanson GD, Babigian HM. Reasons for hospitalization from a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatry Quarterly 48:336–351, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Way BB, Banks S. Clinical factors related to admission and release decisions in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services 52:214–218, 2001Link, Google Scholar

14. Rabinowitz J, Massad A, Fennig S. Factors influencing disposition decisions for patients seen in the psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Services 46:712–718, 1995Link, Google Scholar

15. Slagg NB. Characteristics of emergency room patients that predict hospitalization or disposition to alternative treatments. Hospital Community Psychiatry 44:252–256, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Segal SP, Watson MA, Goldfinger SM, et al. Civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room: II. Mental disorder indicators and three dangerousness criteria. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:753–758, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM. Factors predicting referral to inpatient or outpatient treatment from psychiatric emergency services. Hospital Community Psychiatry 43:703–708, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar