Clinical Factors Related to Admission and Release Decisions in Psychiatric Emergency Services

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of the study was to identify important clinical variables that influence admission and release decisions in psychiatric emergency services. METHODS: Physicians at four urban psychiatric emergency services rated 465 patients on ten clinical dimensions, including depression and psychosis. Information on five other variables—age, gender, ethnicity, diagnosis, and previous inpatient admission—were extracted from the patients' charts, as was information on case disposition. RESULTS: Logistic regression produced a model with five variables that significantly predicted admission or release. In order of importance, they were level of danger to self, severity of psychosis, ability to care for self, impulse control, and severity of depression. The model explained 51 percent of the variance in case disposition and correctly classified 84 percent of the cases. CONCLUSIONS: Guidelines addressing the variables that should be considered in making disposition decisions in psychiatric emergency services should be developed. The study found five variables that should be considered for inclusion.

The psychiatric assessment that is conducted in a psychiatric emergency service and the resulting case disposition decision have major effects—physical, psychological, and fiscal—on patients, families, the community, and insurance providers. Inappropriate release may lead to negative outcomes such as increased risk of suicide and other mortality, increased burden on the support system, deterioration of functioning and exacerbation of symptoms, and violence against another person (1).

Conversely, inappropriate admission to the hospital may be disruptive and stigmatizing (2) and may lead to the loss of employment, housing, and custody of children. It may also have negative financial implications for the dependent family. Further, the decision to hospitalize the patient may determine the choice of subsequent treatment (1) and may reduce the likelihood that the patient will be successfully connected with outpatient treatment (3).

Recent changes in the health care environment may increase both the difficulty and the consequences of the assessment task for psychiatric emergency services. These facilities have become a main entry point for people seeking mental health treatment (4,5), and the patients who visit psychiatric emergency services are more likely to be chronically ill and difficult to engage in treatment (4,5). At the same time, access to inpatient care is increasingly managed, which prevents psychiatrists from opting for hospitalization for borderline cases.

Despite the importance of the task, there are no agreed-on guidelines about which areas of clinical assessment the psychiatric emergency service should focus on in making disposition decisions. In 1983 Apsler and Bassuk (6) recommended that guidelines be created specifying important variables to assess in the psychiatric emergency service. Nearly two decades have passed, and still no guidelines exist. The American Psychiatric Association has developed a guideline for psychiatric evaluation (7), but it does not list the critical factors that require assessment to inform decisions by psychiatric emergency services staff.

Many studies have attempted to identify the important variables associated with dispositions in a psychiatric emergency service (8). Unfortunately, most have relied on retrospective chart review methods. Charts often do not document the outcomes of key clinical assessments. Typically charts include only demographic information; information about diagnosis, presenting problem, and referral source; and case description narratives. Clinical information such as the severity of depression and problems with impulse control often go unrecorded.

Some of the difficulties of chart review methods can be illustrated by looking at assessment of danger to self. First, it is often recorded as a yes or no in the chart under the presenting problem; therefore differences in severity are missed. Further, if the chart has space only to record the primary presenting problem, danger to self could be a secondary problem and not recorded at all. Also, the presenting problem is usually recorded by intake staff, such as a triage nurse, and not by the physician. Thus a chart could indicate that the patient has suicidal ideation, but the physician may have concluded otherwise from the assessment.

This study used improved methods to identify the most important factors in clinical assessments for use in making disposition decisions in a psychiatric emergency service: prospective examination of ten important clinical assessment areas, use of 8-point response scales to capture differing degrees of severity, and collection of information at the end of the physician's assessment just before the disposition decision. The purpose of the study was to provide information to help develop assessment guidelines for use in the psychiatric emergency service.

Methods

After a review of the literature, we decided to focus the investigation on ten areas of clinical assessment: severity of future danger to self, severity of future danger to others, severity of current psychopathology, severity of depression, severity of psychosis, severity of impulse control problems, severity of substance abuse, ability to care for self, degree of social support, and whether the patient was cooperative. Each of these concepts was reported in at least one study to have an important relationship with disposition decisions in the psychiatric emergency service.

A simple 8-point rating tool was created, with 0 indicating none; 1, low; and 7, high. Patient cooperativeness was assessed with a yes-or-no question. Information was also taken from patients' charts; these variables were gender, ethnicity, age, psychiatric diagnosis, whether the patient had any previous psychiatric inpatient admissions, and case disposition. Except for age, all the variables taken from the chart were dichotomized for the analysis: gender was recorded as male or female, ethnicity as white or nonwhite, previous inpatient psychiatric admission as yes or no, disposition as release or admission, and psychiatric diagnosis as major mental illness or non-major mental illness. Diagnoses for a major mental illness were schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, major depressive disorders, and bipolar I disorder. The study included a total of 15 independent variables. The dependent variable was the disposition decision.

Physicians at four urban psychiatric emergency services were asked to use the rating tool during a four- to eight-week study period, depending on the site, just after their assessment interview of each patient and before their disposition decision. The services, which admitted patients to inpatient services in their hospitals, were all located in public general hospitals in New York State. All the services had psychiatric emergency rooms separate from the medical emergency service. A total of 104 doctors participated—23, 29, 19, and 33 at services 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The protocol was approved by the appropriate institutional review boards, and no data were collected without the written consent of the patient.

Ratings for 465 patients were collected—from 74, 182, 101, and 108 patients at psychiatric emergency services 1 through 4, respectively. The ratings were made in the fall of 1994 or the spring of 1995. Physicians were asked to approach each patient who visited the psychiatric emergency service in the data collection period and ask for consent. If consent was given, they were asked to complete the rating tool after their assessment.

Of the 465 patients, 296 were male (63.7 percent), and 236 were white (50.9 percent). The mean±SD age was 37.2±12.9 years. Of the 465 patients, 196 (42 percent) had a diagnosis of a major mental illness. A subset of the 465 patient interviews were videotaped and used to assess interrater reliability among physicians. These results have been reported elsewhere (9). Data on gender, age, ethnicity, and psychiatric diagnosis from earlier, larger studies of psychiatric emergency services 1 and 2 showed similar distributions (10).

First, univariate t tests or chi square analyses were conducted for the 15 indicators to determine whether they significantly differentiated patients admitted from those released. Next, stepwise logistic regression procedures were employed to develop a multivariate model for the dependent variable, disposition. The SPSS software program was used for these analyses (11). In the stepwise regression, the Wald statistic was used to determine the entry order, and the default values of a p value below .05 for entry and a p value below .1 for removal from the model were used.

The model's performance was evaluated in two ways: the proportion of cases correctly classified and the proportion of variance explained. For classification, the logistic model produced predicted scores that can vary from 0 to 1. The dividing point for determining predicted group membership was set at .5, which is very near the overall observed rate of .514. The observed group membership was coded as 0 for release and 1 for an admission.

The proportion of variance explained was determined by adjusting the squared Pearson correlation between the predicted score and actual group membership (12). This statistic is similar to the adjusted R2 produced in ordinary least-squares regression. The adjusted R2 is sensitive to the degree of misclassification. For example, there would be a greater reduction in the adjusted R2 for a case with a predicted score of .04 than for one with a predicted score of .48 if the person was actually admitted. A .04 is a large miss, whereas .48 is a small miss for an observed admission.

The proportion of cases correctly classified and the proportion of variance explained were examined separately for the four hospitals and for 12 of the 104 participating physicians. Only 12 physicians completed ratings for at least nine patients. We chose nine patients as the cutoff because it permitted us to include at least one doctor from each psychiatric emergency service.

Results

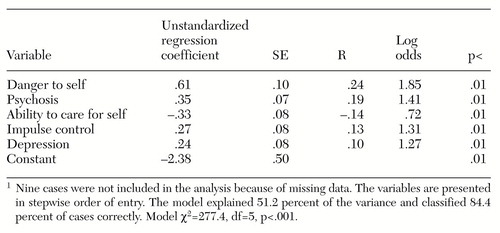

In the univariate analysis the released and admitted groups were significantly different (p<.05) on 11 of 15 variables; the groups were not significantly different in patient cooperation, gender, ethnicity, and age. Forward and backward stepwise logistic regression methods converged to the same multivariate model. As shown in Table 1, the model contained five variables, explained 51.2 percent of the variance in case disposition, and correctly predicted 84.4 percent of the cases. Listed in order of importance according to the R statistic and by entry into the stepwise model, the variables were danger to self, psychosis, care for self, impulse control, and depression.

The R statistic can be used to compare the relative importance of the variables because it adjusts the size of the effect by the standard error of the measure. Log odds, which are presented in Table 1, can also be used to compare the relative importance of the variables, but log odds do not account for the difference in standard error. In logistic regression, a log odds of 1 indicates no effect, whereas an odds greater than 1 indicates a positive effect, and less than 1 indicates a negative effect. Moreover, the odds are proportional; a variable with a log odds of 4 has twice the effect as one with a log odds of 2. Table 1 also lists the unstandardized coefficient for each variable, the standard error, and the significance level.

The stepwise selection process was examined at each step to determine whether any of the 15 variables were important but excluded because of high intercorrelations with the five model terms. Psychopathology was an important variable in early regression steps, but it never entered the model because of shared variance with danger to self and psychosis. Social support did not enter the model because of its correlation with ability to care for self.

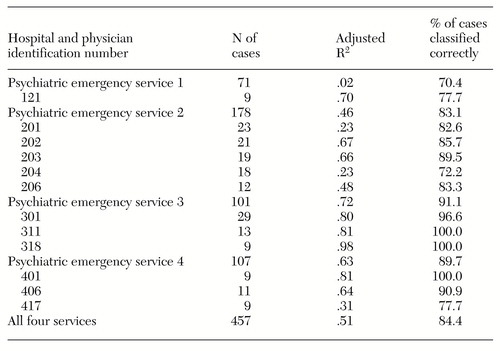

The five-variable model was applied separately to each psychiatric emergency service and to the 12 selected physicians. The results are shown in Table 2. For the four psychiatric emergency services as a whole, the original model classified most of the cases correctly, with percentages varying from 70.4 percent to 91.1 percent. For three of the hospitals the original model also did well in terms of the proportion of variance explained, with percentages varying from 46 percent to 72 percent. However, the model explained only a small proportion of the variance at psychiatric emergency service 1.

The model was more than 80 percent accurate for nine of the selected physicians and explained more than 60 percent of the variance for eight physicians. For three physicians the model explained less than a quarter of the variance in disposition decisions, but it still correctly classified a large proportion of cases.

Discussion

A logistic regression model identified several clinical variables that were important in disposition decisions in the psychiatric emergency room: danger to self, psychosis, ability to care for self, impulse control, and depression. The model classified most cases accurately and explained a large proportion of the variance for most of the psychiatric emergency services and individual physicians. These findings suggest that physicians consider these variables to be the most important areas of assessment for dispositional decisions in the psychiatric emergency service. The other ten variables did not enter the model; however, psychopathology was important in an early regression step, and social support was significantly correlated with the ability to care for self.

These findings are supported in the literature. Danger to self (13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20), psychosis (14,16,18,21,22), impulsive symptoms (15,16,20,23), depression (16,21), and ability to care for self (15,18,21,24,25) have all been reported to be associated with disposition. However, in one study danger to self was not included in the multivariate model because clinical variables were more important (26).

Psychopathology (15,18,19,24,26) and diagnosis (14,18,19,21,22,23,25,26,27) have also been found to be related to dispositions in the psychiatric emergency service; however, it is questionable whether these concepts are independent of the five areas in our model. Previous studies have usually found that diagnoses defined by psychotic symptoms increase the likelihood of hospital admission. Studies in which more than one of three variables—psychopathology, specific symptoms, and diagnosis—have been included in a multivariate model have found mixed results in terms of whether each variable explains a unique portion of the variance in disposition decisions (14,21,22,24). In our study, diagnosis was an important variable in the univariate analysis but not in any stage of the multivariate analysis. Psychopathology had a large Wald statistic in early stages of the multivariate analysis but never entered the model.

Previous studies have found an important relationship between disposition in the psychiatric emergency service and social support (13,19,20,28). In our study, social support did not enter the multivariate model, but it did have a significant relationship with the variable ability to care for self, which entered the model. Future research should focus on untangling the relationships between areas of assessment in the psychiatric emergency service, as was attempted by Way (29).

For the other variables that did not enter the multivariate model in our study, previous investigations reported conflicting results. Some studies reported that certain variables were strongly associated with disposition, whereas other studies reported opposite findings. Conflicting results have been reported for danger to others (13,14,15,16,17,20,26), substance abuse (13,18,20,26), client cooperation (13,18,20,21), previous psychiatric inpatient care (14,18,24,27,28), and demographic variables (21,22,23,24,26,27).

The five-variable logistic model performed poorly at psychiatric emergency service 1. This facility had a very high admission rate, and only a handful of persons in the sample were released. If the study had included a larger sample from this hospital, we may have been able to clarify why this result was obtained. Staff at this hospital who were interviewed suggested that the high admission rate was partly due to the remoteness of the hospital in its urban location; in many cases persons are informally "preadmitted" before they are transported to the psychiatric emergency service. Also, although the model worked well for most of the individual physicians, additional cases would permit a more comprehensive analysis of individual physicians.

The results presented here were based on data collected in four urban public psychiatric emergency services in New York State. However, there is no reason to believe that the results would not apply to other psychiatric emergency services. The assessment of key issues such as psychosis, depression, danger to self, and impulse control would be important for disposition decisions in all settings.

The results of this study suggest that the factors associated with disposition decisions in psychiatric emergency services are similar across hospitals and physicians. If a patient is rated high on danger to self, psychosis, depression, and lack of impulse control and is rated low on ability to care for self, the patient will very likely be admitted to an inpatient setting. This outcome is likely no matter which physician does the rating. Our findings imply agreement on the importance of these assessment areas. However, they do not imply that doctors agree on how to measure each of the five areas. In another part of this study reported elsewhere (9), eight senior psychiatrists each rated 30 videotaped patients with the same simple rating tool. The psychiatrists had high interrater agreement on severity of psychosis and depression and low interrater agreement on danger to self, impulse control, and ability to care for self.

Conclusions

We start the new millennium without guidelines specifying the crucial dimensions of assessment in psychiatric emergency services. In this time-pressured environment, we should first focus on collecting the most important information. It has been recommended that the field of emergency psychiatry develop guidelines that specify the crucial components. Convening expert panels is one approach that has been tried (30) and that could be used in the future. In addition to identifying the most important components, much effort is needed to improve their measurement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant MH-51359 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank Jeryl Mumpower, Ph.D., Thomas Stewart, Ph.D., and Michael Allen, M.D.

Dr. Way is affiliated with the New York State Office of Mental Health, 44 Holland Avenue, Albany, New York 12229 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Banks is with the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester.

|

Table 1. Stepwise logistic regression model of predictors of hospital admission or release from the psychiatric emergency service for 456 patients1

1 Nine cases were not included in the analysis because of missing dataThe variables are presented in stepwise order of entry. The model explained 51.2 percent of the variance and classified 84.4 percent of cases correctly. Model χ2=277.4, df=5, p<.001.

|

Table 2. Results of using the multivariate model to predict hospital admission or release from the psychiatric emergency service at four facilities and with different physicians

1. Gerson S, Bassuk E: Psychiatric emergencies: an overview. American Journal of Psychiatry 137:1-11, 1980Link, Google Scholar

2. Stroul B: Residential crisis services : a review. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:1095-1099, 1988Abstract, Google Scholar

3. Klinkenberg WD, Calsyn RJ: Predictors of receiving aftercare 1, 3, and 18 months after a psychiatric emergency room visit. Psychiatric Quarterly 70:39-51, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Bassuk EL: Psychiatric emergency services: can they cope as last-resort facilities? New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 28, 11-20, 1985Google Scholar

5. Hughes DH: Trends and treatment models in emergency psychiatry. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:927-928, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Apsler R, Bassuk E: Differences among clinicians in the decision to admit. Archives of General Psychiatry 40:1133-1137, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for psychiatric evaluation of adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(Nov suppl):63-80, 1995Google Scholar

8. Marson DC, McGovern MP, Pomp HC: Psychiatric decision making in the emergency room: a research overview. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:918-925, 1988Link, Google Scholar

9. Way BB, Allen MH, Mumpower JL, et al: Interrater agreement among psychiatrists in psychiatric emergency assessments. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1423-1428, 1998Link, Google Scholar

10. DeMasi M: Evaluation of the Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program. Albany, New York State Office of Mental Health, 1994Google Scholar

11. SPSS Reference Guide. Chicago, SPSS, 1990Google Scholar

12. Neter J, Wasserman W, Kutner MH: Applied Linear Statistical Models: Regression, Analysis of Variance, and Experimental Designs, 3rd ed. Homewood, Ill, Irwin, 1990Google Scholar

13. Feinstein R, Plutchik R: Violence and suicide risk assessment in the psychiatric emergency room. Comprehensive Psychiatry 31:337-343, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Friedman S, Margolis R, David OJ, et al: Predicting psychiatric admission from an emergency room: psychiatric, psychosocial, and methodological factors. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 171:155-158, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Segal SP, Watson MA, Goldfinger SM, et al: Civil commitment in the psychiatric emergency room: I. the assessment of dangerousness by emergency room clinicians. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:748-752, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Mezzich JE, Evanczuk KJ, Mathias RJ, et al: Symptoms and hospitalization decisions. American Journal of Psychiatry 141:764-769, 1984Link, Google Scholar

17. Holmes W, Solomon P: Organizational and client influences on psychiatric admissions. Psychiatry 44:201-209, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Tischler GL: Decision-making process in the emergency room. Archives of General Psychiatry 14:69-78, 1966Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Rose SO, Hawkins J, Apodaca L: Decision to admit. Archives of General Psychiatry 34:418-421, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Gillig PM, Hillard JR, Deddens JA, et al: Clinician's self-reported reactions to psychiatric emergency patients: effect on treatment decisions. Psychiatric Quarterly 61:155-162, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Slagg NB: Characteristics of emergency room patients that predict hospitalization or disposition to alternative treatments. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:252-256, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

22. Way BB, Evans ME, Banks SM: Factors predicting referral to inpatient or outpatient treatment from psychiatric emergency services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:703-708, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Johnson JH, Klingler DE, Giannetti RA: A study of mental status and anamnestic factors related to the decision for inpatient or outpatient treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology 35:844-850, 1979Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Feigelson EB, Davis EB, MacKinnon R, et al: The decision to hospitalize. American Journal of Psychiatry 135:354-357, 1978Link, Google Scholar

25. Mezzich JE, Evanczuk KJ, Mathias RJ, et al: Admission decisions and multiaxial diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 41:1001-1004, 1984Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. McNiel DE, Myers RS, Zeiner HK, et al: The role of violence in decisions about hospitalization from the psychiatric emergency room. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:207-212, 1992Link, Google Scholar

27. Hanson GD, Babigian HM: Reasons for hospitalization from a psychiatric emergency service. Psychiatric Quarterly 48:336-351, 1974Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Mendel WM, Rapport S: Determinants of the decision for psychiatric hospitalization. Archives of General Psychiatry 20:321-328, 1969Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Way BB: Decision Making in Psychiatric Emergency Rooms. Albany, NY, Department of Public Administration and Policy, University at Albany, State University of New York, 1997Google Scholar

30. Dawes SS, Bloniarz PA, Mumpower JL, et al: Supporting Psychiatric Assessment in Emergency Rooms. Albany, NY, University at Albany, Center for Technology in Government, 1995Google Scholar