Cost of Care for Medicaid Recipients With Serious Mental Illness and HIV Infection or AIDS

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To assist in developing public policy about the feasibility of HIV prevention in community mental health settings, the cost of care was estimated for four groups of adults who were eligible to receive Medicaid: persons with serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS, persons with serious mental illness only, persons with HIV infection or AIDS only, and a control group without serious mental illness, HIV infection, or AIDS. METHODS: Claims records for adult participants in Medicaid fee-for-service systems in Philadelphia during 1996 (N=60,503) were used to identify diagnostic groups and to construct estimates of reimbursement costs by type of service for the year. The estimates included all outpatient and inpatient treatment costs per year per person and excluded pharmacy costs and the cost of nursing home care. Persons with severe mental illness, HIV infection, or AIDS had received those diagnoses between 1985 and 1996. RESULTS: Persons with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS had the highest annual medical and behavioral health treatment expenditures (about $13,800 per person), followed by persons with HIV infection or AIDS only (annual expenditures of about $7,400 per person). Annual expenditures for persons with serious mental illness only were about $5,800 per person. The control group without serious mental illness, HIV infection, or AIDS had annual expenditures of about $1,800 per person. CONCLUSIONS: Given the high cost of treating persons with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS, the integration of HIV prevention into ongoing case management for persons with serious mental illness who are at risk of infection may prove to be a cost-effective intervention strategy.

Previous research has suggested that persons with serious mental illness are at heightened risk of contracting HIV and developing AIDS (1). Prevalence rates of HIV infection or AIDS among persons with serious mental illness in the United States have been estimated to range between 5.2 percent and 22.9 percent (1,2,3,4,5,6,7), compared with .3 percent in the general population (8). A recent study focusing on a large urban population of Medicaid recipients in Philadelphia found the treated prevalence of HIV infection among Medicaid recipients with a serious mental illness to be 3.7 percent (1). These markedly elevated rates among persons with serious mental illness are believed to be due to that group's higher prevalence of HIV-related risk factors, such as low socioeconomic status and high rates of substance use, homelessness, and risky sexual behavior, including unprotected sex and sex for sale (9,10).

Mounting evidence of high infection rates among persons with serious mental illness underscores the importance of examining the extent and type of services being provided to these individuals. Regrettably, little is known about the cost of care for this group. In this study we developed estimates of the cost of care for persons with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS and compared the cost with that for persons with serious mental illness only, with HIV infection or AIDS only, and without serious mental illness, HIV infection, or AIDS. This information may be useful in developing public policy related to HIV prevention for persons with serious mental illness.

Background

Our literature review on the costs of treating persons with serious mental illness, HIV, or AIDS found wide variability. Annual cost estimates for treating an individual with serious mental illness in the United States ranged from $9,506 to more than $25,940 (11,12,13,14,15,16). For treatment of HIV and AIDS, annual costs per person ranged from a low of $22,000 to a high of more than $33,000 (17,18,19,20,21). Pharmacy costs consisted of about 9 percent of the total costs for serious mental illness; for HIV and AIDS, pharmacy costs were between 9 percent and 30 percent of the total cost. All cost estimates, at a minimum, included direct treatment expenditures, such as costs of ambulatory care and hospitalization, and most estimates included pharmacy costs.

Over the past decade, Medicaid has funded the largest share of treatment for people with mental disorders, particularly those with severe mental illness (22). Likewise, Medicaid has accounted for the largest portion of AIDS-related public funding in many states (23,24). Most studies of costs of care for persons with serious mental illness have not included expenditures for the newer atypical antipsychotic medications, and most cost estimates for treatment of persons with HIV infection or AIDS have not been recent enough to document the cost of implementing drug therapy earlier in the disease cycle and the cost substitution associated with newer drug combination therapies in place of inpatient care. In addition, we could find no studies that addressed the cost of treatment for HIV infection and AIDS among persons with comorbid serious mental illness.

Despite the lack of research, we hypothesized that the cost of treating persons with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS would be substantially higher than the cost of treating persons with a serious mental illness only, persons with HIV infection or AIDS only, or persons without a serious mental illness, HIV infection, or AIDS. Previous studies have noted that persons with serious mental illness have higher medical costs than persons without serious mental illness (25,26). Persons with comorbid substance use and psychotic disorders have the highest medical costs (25).

From a public policy standpoint, understanding these differences is an important factor in improving allocation of scarce resources for prevention programs, given the potential for cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention among persons with serious mental illness. Identification of utilization patterns and expenditures for general health care, specialty mental health care, and drug and alcohol treatment provides a means for assessing the nature of the treatment being received for co-occurring mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS and also suggests potential targets for prevention strategies.

Methods

Data sources

The data used in this study on inpatient and outpatient health care utilization came from Medicaid fee-for-service claims and eligibility records for all Medicaid-eligible recipients in Philadelphia in 1996. These claims are ordinarily used for record keeping and auditing by the Department of Public Welfare. However, they were ideal for this study, because they represent a record of health care utilization for persons receiving welfare-related benefits, many of whom are chronically ill or disabled. The data contain both person-level sociodemographic information and service-level information, such as type of service, date of service, provider, diagnostic codes, and cost. Data on pharmacy, home health care, and nursing home use were incomplete for 1996 and were excluded from the estimates.

Study participants

Persons selected for this study were eligible to receive Medicaid services under a fee-for-service system. Individuals aged 18 to 64 years who resided in Philadelphia and who were continuously enrolled in a Medicaid fee-for-service system during 1996 were eligible (N=60,503). This population was divided into four groups. The study group consisted of persons with diagnoses of a serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS (N=268); diagnoses were identified in claims data for the period between 1985 and 1996. The three comparison groups were persons with a diagnosis of a serious mental illness only (N=8,513), persons with a diagnosis of HIV infection or AIDS only (N=410), and persons with neither a serious mental illness nor HIV or AIDS (the control group) (N=51,312).

Persons were deemed to be seriously mentally ill on the basis of a claim for treatment that included a diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9 code 295) or major affective disorder (ICD-9 code 296) and at least one inpatient or two outpatient treatment contacts for these diagnoses, following the protocol developed by Lurie and associates (27) to ensure a more accurate diagnosis. ICD-9 codes 042 (HIV infection with specified conditions), 043 (HIV infection causing other specified conditions), and 044 (other HIV infections) were used to identify an HIV-related diagnosis.

Analyses

Annual costs were aggregated for all groups by using 1996 Medicaid-reimbursed claims for inpatient and outpatient services separately for health, drug and alcohol treatment services, and mental health services. Costs are reported in 1996 dollars. Service records were constructed at the individual level to reflect the total number of inpatient days, outpatient visits, and reimbursed costs. We used descriptive analysis to compare the characteristics of the four groups, the types and intensities of services used, and the associated costs. Mean expenditures per eligible Medicaid recipient were determined, and cost distributions were examined for each group. Chi square tests and analysis of variance were used to assess the statistical significance of differences between the groups in case-mix characteristics, rates of service utilization, and costs. SAS for Windows, version 8.2, PROC FREQ and PROC MEANS were used for the analyses.

Results

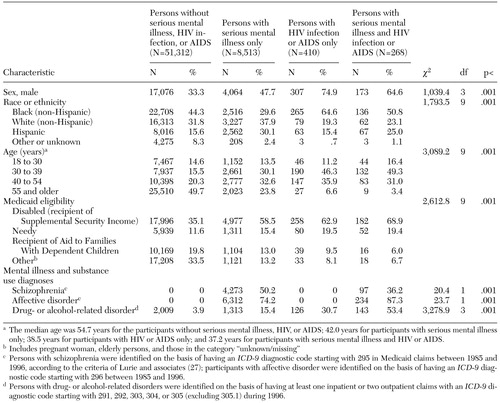

Characteristics of participants

As Table 1 shows, statistically significant differences between groups were found for all characteristics examined. Persons with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS (N=268) made up .4 percent of the total population. The group with comorbid disorders was younger than the group with serious mental illness only (median ages of 37 and 42 years, respectively) and included a larger proportion of men (65 percent compared with 48 percent), black persons (51 percent compared with 30 percent), and disabled persons (69 percent compared with 59 percent). However, a smaller percentage of the persons in the group with comorbid disorders had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (36 percent compared with 50 percent). Thus, compared with the group with serious mental illness only, the group with comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS was disproportionately represented by younger black men with affective disorders.

The group with comorbid disorders was similar to the group with HIV infection or AIDS only in median age (37 and 38 years, respectively) but included fewer men (65 percent compared with 75 percent) and black individuals (51 percent compared with 65 percent), a slightly larger proportion of disabled persons (69 percent compared with 63 percent), and a much higher percentage of persons with a drug- or alcohol-related disorder (53 percent compared with 31 percent).

Compared with persons in the control group, the group with comorbid disorders was younger and included a larger proportion of participants who were men, black, and disabled and who had a drug- or alcohol-related disorder. The control group for this analysis represented individuals who did not voluntarily enroll in a Medicaid managed care program before their enrollment was mandated. They were more likely to be disabled than the general Medicaid population, as evidenced by the large proportion of participants in the control group who were receiving SSI disability benefits (35 percent).

Service utilization

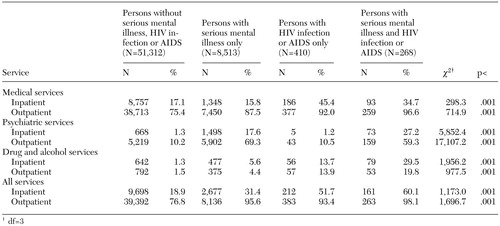

Utilization rates. Health care utilization rates were calculated by using the number of all eligible persons in each group as the denominator for the group and the number of persons who used the service as the numerator. As anticipated, compared with the other study groups, the group with serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS had the highest combined annual rate of use of inpatient medical, psychiatric, and drug and alcohol treatment services (60 percent) and the highest annual rate of outpatient service use (98 percent) (Table 2).

The group with HIV or AIDS only had the second highest annual rate of hospital use overall (52 percent) and of outpatient service use (93 percent). Rates for the group with serious mental illness only were 31 percent for inpatient service use and 96 percent for outpatient service use. Compared with the other groups, the control group had a notably lower rate of inpatient service use (19 percent) and a lower but still substantial rate of outpatient service use (77 percent).

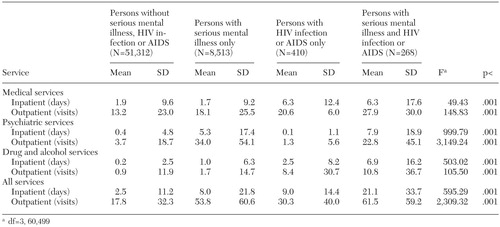

Inpatient days.Persons with serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS had a mean of 21.1 days of any kind of hospitalization in 1996 (Table 3). The majority of those days were for psychiatric care (mean=7.9 days) and drug and alcohol treatment services (mean=6.9 days); the group had a mean of 6.3 days of inpatient medical services. In contrast, the mean for the group with HIV infection or AIDS only was nine days for inpatient services. The group with HIV or AIDS only was similar to the group with comorbid disorders in the amount of inpatient medical care received (a mean of 6.3 days, compared with 6.3 days) but had many fewer inpatient days of psychiatric treatment (a mean of .1 day, compared with 7.9 days) and drug and alcohol treatment (mean of 2.5 days, compared with 6.9 days).

Compared with the group with serious mental illness only, the group with comorbid disorders had many more inpatient days for medical treatment (a mean of 1.7 days compared with 6.3 days), more inpatient psychiatric days (a mean of 5.3 days compared with 7.9 days), and more drug and alcohol treatment days (a mean of one day compared with 6.9 days). The control group had the fewest number of hospital days per person (a mean of 2.5 days), with a mean of 1.9 days of inpatient medical care, .4 day of psychiatric care, and .2 day of drug and alcohol treatment.

Outpatient visits. Similar to the inpatient utilization rates, outpatient treatment rates were highest for the group with comorbid disorders (a mean of 61.5 visits in 1996), followed by the group with serious mental illness only (53.8 visits) and the group with HIV or AIDS only (30.3 visits) (Table 3). The mean was 14.1 outpatient visits for the control group. For the group with comorbid disorders, these visits were most often for medical care (a mean of 27.9 visits), followed by psychiatric care (22.8 visits), and were less often for drug and alcohol treatment (10.8 visits). Overall, the group with comorbid disorders had a mean of more than one visit per week to a health care provider.

Service costs

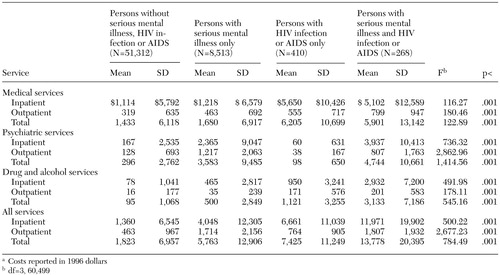

Total costs.Table 4 shows overall cost patterns for the study groups. The group with serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS had the highest expenditures, a total of $13,778 annually per person. In comparison, total expenditures for services was $7,425 per person for the group with HIV infection or AIDS only (54 percent of the mean total expenditures for the group with comorbid disorders) and $5,763 per person for the group with serious mental illness only (42 percent of the mean total expenditures for the group with comorbid disorders). For the control group, total expenditures per person were $1,823, or 13 percent of the expenditures for the group with comorbid disorders.

A synthetic estimate of the total cost of care was calculated by using the sum of the mean individual expenditures for the group with serious mental illness only and the group with HIV or AIDS only. The estimate—$13,188—was only slightly lower than the actual mean costs for the group with comorbid disorders (a mean of $13,778). The difference between the synthetic estimate and the mean expenditures for the group with comorbid disorders appeared to be the result of high expenditures for drug and alcohol treatment services in this group (a mean of $3,133), which were considerably higher than the expenditures for either of the single-diagnosis groups ($500 for the group with serious mental illness only and $1,121 for the group with HIV infection or AIDS only).

Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of costs by service category for each group. In ranking the costs within each group, we found that psychiatric costs were highest for the group with serious mental illness only and the group with comorbid disorders, drug and alcohol treatment expenditures were highest in the group with HIV infection or AIDS only and the group with comorbid disorders, and medical services expenditures were about equivalent in the group with comorbid disorders and the group with HIV infection or AIDS only. The differences in expenditures for inpatient and outpatient services were statistically significant across all groups.

Cost distribution. For more than 20 percent of the group with comorbid disorders, average annual expenditures were greater than $20,000, compared with less than 10 percent of the group with HIV infection or AIDS only and less than 7 percent of the group with serious mental illness only. In comparison, only 2 percent of persons in the control group had mean costs above $20,000 a year.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that costs for Medicaid-reimbursed health care were substantially higher among persons with co-occurring serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS than for persons with HIV or AIDS only or persons with serious mental illness only and much higher than the costs for a control group of persons with disabilities not related to these target conditions. Although the sociodemographic case mix of each group differed, the costs for the group with comorbid disorders are likely to be higher than reported, given that this group had the lowest median age of the four groups.

The costs presented here represent only the costs of direct care related to inpatient and outpatient medical, mental health, and drug and alcohol treatment. The findings for the cost categories in each area confirmed our expectations that mental health costs would make up the bulk of expenditures for persons with serious mental illness, whereas medical care costs would make up the bulk of costs for those with HIV or AIDS. Many of these health care costs may be unrelated to AIDS itself but may be associated with high-risk behavior in general.

Finally, costs for the group with comorbid disorders were more than the sum of costs for the two single-diagnosis groups; the former group used more drug and alcohol treatment services. The high costs for drug and alcohol services for the group with comorbid disorders may be related to greater recognition and subsequent treatment of substance abuse disorders in this group in the context of their receiving treatment for AIDS.

It is important to note several caveats regarding the characteristics of the study population. First, Medicaid recipients constitute a more chronically disabled population than the general population. Second, persons in this study, particularly those in the control group, constituted an even more seriously ill population than typical Medicaid enrollees because of the loss of younger, healthier Medicaid recipients to voluntary Medicaid health maintenance organizations during the study period. Third, there is a potential case identification issue regarding whether the group with comorbid disorders might represent a substance-abusing population with mental health problems rather than a psychiatrically disabled population. Given that only 8.5 percent of the participants in the group with comorbid disorders had a substance abuse claim of any type lends support to classifying these individuals as seriously mentally ill.

With respect to our cost estimates, we underestimated the cost of treatment across groups, because we excluded data on pharmacy, nursing home, and home health care claims and on out-of-pocket expenses. Furthermore, Medicare costs for persons with dual eligibility for Medicaid and Medicare benefits were not included. Given that 12 to 13 percent of persons living with AIDS are covered by Medicare under Social Security Disability Insurance (19), the cost of Medicare services may be relevant.

To account for some of the pharmacy cost information that was not included in the claims data files, it should be noted that the mean annual wholesale drug costs during the study period for HIV infection and AIDS ranged from $2,500 for nucleosides to $8,000 for protease inhibitors (28) to about $12,000 for combination antiretroviral therapy (29). The cost of atypical antipsychotic medication ranged from $2,500 to $5,200 a year, according to data on the wholesale cost of medications reported by the Ohio Department of Mental Health (30). Similar costs were found in a prospective study of patients with schizophrenia discharged from Maryland state psychiatric facilities in 1998 (31). With respect to the cost of nursing home and home health care for persons with AIDS, few recent studies have estimated these costs, because the newer treatment technologies, such as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), have become more common. Additionally, we used 1996 cost estimates, and it is probable that current expenditure patterns would differ, particularly given the advances in pharmacologic treatment of HIV infection and AIDS.

Despite the limitations of the data, which led to a conservative estimate of costs for the group with comorbid disorders, our study is important for public policy purposes, because 68 percent of persons with HIV infection or AIDS were dependent on public programs, particularly Medicaid, in 1996. In addition, a large proportion of persons with serious mental illness who had previously been institutionalized were living in the community in 1996 and using Medicaid as their primary source of health care funding. We can expect expenditures across the lifetimes of these persons to continue to grow with the expansion of HAART treatment, which leads to increased longevity among persons with HIV infection and AIDS. Like serious mental illness, HIV infection and AIDS are rapidly becoming chronic illnesses, and much of the cost of these illnesses is being borne by the public sector.

Furthermore, the potential for even higher costs exists as pressure is placed on the Medicaid program to allow individuals with HIV infection to become eligible for health benefits before they become disabled with AIDS. The cost burden on the Medicaid program will very likely increase in the future. One factor in this increase is that, unlike participants in Medicare and other insurance plans, Medicaid recipients are covered for their drug costs.

The high costs of care support the need for integration of psychiatric, substance use, and medical treatment, perhaps by use of disease management approaches. This recommendation is particularly relevant, because behavioral health care is carved out from medical care in most managed care plans and because prevention strategies for persons with serious mental illness are lacking (32,33,34). Adding to the health risks of persons with serious mental illness are weight management problems and associated medical consequences related to the use of the newer atypical antipsychotics and other psychotropic medications. All of these require interdisciplinary approaches to treatment.

On the basis of the evidence that the seriously mentally ill population is at high risk of contracting HIV infection and developing AIDS, prevention and early identification has been recommended (35). As more persons with serious mental illness are using the HAART regimen for longer periods, pharmacy costs are likely to increase for this group as well. Case management could be effectively used to provide interventions to improve adherence to these complex treatment regimens. Therefore, information on the prevalence of comorbid serious mental illness and HIV infection or AIDS, combined with estimates of the cost of current treatment, is extremely relevant for public policy makers who need to predict the cost consequences of newer interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant P30-AI45008 from the National Institute of Nursing Research and by the developmental core of the Penn Center for AIDS Research.

The authors are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research at the University of Pennsylvania, 3535 Market Street, Room 3014, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-2648 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Rothbard and Dr. Blank are also affiliated with the Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics and the Penn Center for AIDS Research at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Metraux is also affiliated with the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of adults in four diagnostic groups in continuous enrollment in a Medicaid fee-for-service system in Philadelphia during 1996 (N=60,503)

|

Table 2. Utilization of treatment services by adults in four diagnostic groups in continuous enrollment in a Medicaid fee-for-service system in Philadelphia during 1996 (N=60,503)

|

Table 3. Amount of treatment services utilized by adults in four diagnostic groups in continuous enrollment in a Medicaid fee-for-service system in Philadelphia during 1996 (N=60,503)

|

Table 4. Cost of treatment services utilized by adults in four diagnostic groups in continuous enrollment in a Medicaid fee-for-service system in Philadelphia during 1996 (N=60,503)a

a Costs reported in 1996 dollars

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al: Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatric Services 53:868–873, 2002Link, Google Scholar

2. Carey MP, Weinhardt LS, Carey KB: Prevalence of infection with HIV among the severely mentally ill: review of research and implications for practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26:262–268, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

3. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:159–169, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

4. Cournos F, Guido JR, Coomaraswamy S, et al: Sexual activity and risk of HIV infection among patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:228–232, 1994Link, Google Scholar

5. Knox MD, Boaz TL, Friedrich MA, et al: HIV risk factors for persons with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal 30:551–563, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. McKinnon K, Cournos F: HIV infection linked to substance use among hospitalized patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1269, 1998Link, Google Scholar

7. Walkup J, Crystal S, Sambamoorthri U: Schizophrenia and major affective disorder among Medicaid recipients with HIV/ AIDS in New Jersey. American Journal of Public Health 89:1101–1103, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: New Cases of HIV Infection in the United States. Atlanta, CDC, 1998. Available at www.cdc.gov/faststats/pdf/hus99t55.pdfGoogle Scholar

9. Rosenberg SD, Trumbetta SL, Mueser KT, et al: Determinants of risk behavior for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in people with severe mental illness. Comprehensive Psychiatry 42:263–271, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Brunette MF, Mercer CC, Carlson CL, et al: HIV-related services for persons with severe mental illness: policy and practice in New Hampshire community mental health. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 27:347–353, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kronick R, Dreyfus T, Lee L, et al: Diagnostic risk adjustment for Medicaid: the disability payment system. Health Care Financing Review 17(3):7–33, 1996Google Scholar

12. Dickey B, Normand ST, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a 4-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945–952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Mauskopf JA, David K, Grainger DL, et al: Annual health outcomes and treatment costs for schizophrenia populations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 19):14–22, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

14. McCombs JS, Nichol MB, Johnstone BM, et al: Antipsychotic drug use patterns and the cost of treating schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 51:525–527, 2000Link, Google Scholar

15. Foote SM, Hogan C: Disability profile and health care costs of Medicare beneficiaries under age sixty-five. Health Affairs 20(6):242–253, 2001Google Scholar

16. Rothbard AB, Kuno E: Effects of managed care on cost and utilization of services for persons with severe mental illness. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, August 20–24, 1999Google Scholar

17. Hellinger FJ: The lifetime cost of treating a person with HIV. JAMA 270:474–478, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Dreyfus T, Kronick R, Tobias C: Using Payment to Promote Better Medicaid Managed Care for People With AIDS. Portland, Me, National Academy for State Health Policy, 1997Google Scholar

19. Fasciano NJ, Cherlow AL, Turner BJ, et al: Profile of Medicare beneficiaries with AIDS: application of an AIDS casefinding algorithm. Health Care Financing Review 19(3):19–38, 1998Google Scholar

20. Mitchell JM, Anderson KH: Effects of case management and new drugs on Medicaid AIDS spending. Health Affairs 19(4):233–243, 2000Google Scholar

21. AIDS Related Costs and Expenditures in New York State. Albany, New York State Department of Health, 1994. Available at www.health.state.ny.us/nysdoh/hivaids/4-aids94.pdfGoogle Scholar

22. Coffey RM, Mark T, King E, et al: National Estimates of Expenditures for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. SAMHSA pub no SMA-00–3499. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Center for Mental Health Services, July 2000Google Scholar

23. Green J, Arno PS: The "medicaidization" of AIDS: trends in the financing of HIV-related medical care. JAMA 264:1261–1266, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Morin SF, Charlebois ED: Expanding access to early HIV care: new challenges for federal health policy. AIDS and Public Policy Journal 15(2):65–74, 2000Google Scholar

25. Dickey B, Normand ST, Weiss RD, et al: Medical morbidity, mental illness, and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services 53:861–867, 2002Link, Google Scholar

26. Dixon L, Postrado L, Delahanty J, et al: The association of medical comorbidity in schizophrenia with poor physical and mental health. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:496–502, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69–71, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

28. Drug Topics Red Book. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics, 1996Google Scholar

29. Hirschel B, Francioli P: Progress and problems in the fight against AIDS. New England Journal of Medicine 338:906–908, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Buckley PF: Treatment of schizophrenia: let's talk dollars and sense. American Journal of Managed Care 4:369–383, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

31. Kelly DL, Nelson MW, Love RC, et al: Comparison of discharge rates and drug costs for patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone or olanzapine. Psychiatric Services 52:676–678, 2001Link, Google Scholar

32. Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, et al: Receipt of preventive medical services at psychiatric visits by patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:884–887, 2002Link, Google Scholar

33. Goldberg RW, Seybolt DC, Lehman A: Reliable self-report of health service use by individuals with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 53:879–881, 2002Link, Google Scholar

34. Cradock-O'Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, et al: Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 53:874–878, 2002Link, Google Scholar

35. Blank M, Rothbard A, Metraux S: Evidence for integration of HIV prevention into case management. Presented at a National Institute of Mental Health conference on Evidence in Mental Health Services Research: What Types, How Much, and Then What? Washington, DC, April 1, 2002Google Scholar