Receipt of Preventive Medical Services at Psychiatric Visits by Patients With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

The authors used data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey from 1992 to 1999 on 3,198 office visits to explore the extent to which psychiatrists provide clinical preventive medical services to patients with severe mental illness. Preventive services were provided during 11 percent of the visits. A multivariate analysis showed that preventive services were more likely to have been provided for patients with a chronic medical condition, for patients who were also seen by a nurse or other health provider during the visit, in rural areas, and during longer visits. Preventive services were less likely to have been provided during visits to health maintenance organizations and visits that took place later in the study period.

Persons with severe and persistent mental illnesses suffer from high rates of comorbid medical illnesses, some of which may be attributable to unhealthy behaviors (1,2). Weight gain and other effects of psychotropic medications also contribute to the burden of medical conditions in this population. Because patients who have severe mental illness may face barriers in obtaining primary care services, they may not receive clinical preventive medical services appropriate to their needs, such as blood pressure screening and exercise counseling (1).

The feasibility and acceptability of psychiatrists' providing certain primary care services for their patients with severe mental illness are controversial (3,4). Many psychiatrists are interested in providing medical preventive services but cite lack of training as a major barrier to their delivery of these services (5). On a panel convened to recommend primary care services that could be appropriately delivered by psychiatrists who have some primary care training, a majority agreed that most preventive services could be provided by psychiatrists (6). At least one training program is under way to teach ambulatory care skills to psychiatry residents (7).

We sought to determine the extent to which psychiatrists in the United States provide clinical preventive medical services during office visits by patients with severe mental illness as well as factors associated with providing these services. We hypothesized that preventive counseling would occur more commonly during visits by patients with certain chronic medical conditions.

Methods

Data were obtained from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), an ongoing annual survey of randomly selected U.S. office-based physicians conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) (8). We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of outpatient visits to psychiatrists by persons with severe mental illness from 1992 to 1999. Severe mental illness was defined as an ICD-9 diagnosis of a psychotic disorder (ICD-9-CM codes 295 and 297 to 298.9), bipolar disorder (codes 296.4 to 296.8), or recurrent depression (codes 296.3 and 301). We included visits by patients aged 18 or older who were white, African American, or Hispanic.

The NAMCS includes visits to private offices, freestanding and local government clinics, community health centers, and health maintenance organizations. It excludes visits to hospital outpatient departments, federally employed physicians, and institutional settings such as the Department of Veterans Affairs medical facilities. Response rates ranged from 68 percent to 73 percent for the study period (8). Detailed information about the design of the NAMCS and data collection forms may be found at www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/ahcd1.htm.

In the survey, physicians record information about their encounters with patients during one randomly assigned week of the year. Information on patients' sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses, and treatment and certain characteristics of the practice setting is collected. For independent variables, we used information on patients' age, sex, race or ethnicity, payment source, psychiatric diagnosis, and geographic region as well as whether they visited a practice in a metropolitan or a rural location, whether they had a chronic medical condition, whether the visit was an initial or a follow-up visit, and the amount of time spent with the psychiatrist.

We also examined whether other health care providers saw the patient during that visit. We noted evidence of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder, and depression. A chronic medical condition was defined as documentation of diabetes, obesity, or hypertension, which physicians reported by checking a box. Patients were also considered to have diabetes if diabetic medication was listed. Physicians could also record up to three diagnoses of any type by writing on the visit form.

Our outcome of interest was receipt of any clinical preventive medical service. We defined these services broadly to include counseling for smoking, diet, weight, exercise, cholesterol, sexually transmitted diseases, injury prevention, HIV infection, prenatal care, breast examinations, or skin examinations. We also included measurement of blood pressure and laboratory tests for cholesterol, HIV infection or other sexually transmitted diseases, and prostate-specific antigen. Physicians could record these services by checking a box on the visit form.

We conducted chi square tests to investigate whether patient characteristics and characteristics of the practice setting varied by receipt of clinical preventive medical services. We developed logistic regression models to examine associations between these factors and receipt of preventive services.

The NAMCS is based on complex multistage sampling designs. However, for confidentiality reasons the NCHS does not release the primary sampling units for most years of the survey. Because our analysis tested a hypothesis of an association, we report results based on unweighted data (9). We performed sensitivity analyses to approximate the complex survey designs of the NAMCS by using the survey weights in the analysis and the strata of geographic region and urban or rural designation as a proxy for primary sampling units. These results were essentially similar to those obtained through logistic regression models using unweighted data.

Results

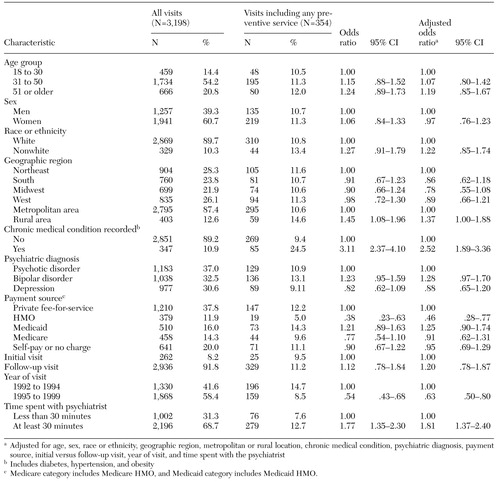

From 1992 to 1999, there were 3,198 visits to office-based psychiatrists for patients who met the criteria for severe mental illness. Demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients' visits are summarized in Table 1. More than half of the visits (54.2 percent) were for patients between the ages of 31 and 50 years; 60.7 percent were for women, and 89.7 percent were for whites. Almost 90 percent of the visits took place in metropolitan areas, and about 30 percent of the visits were covered by Medicaid or Medicare.

We identified 354 visits (11 percent) during which any clinical preventive medical service was provided. For 58 percent of these visits, one preventive service was reported; for 21 percent of visits, two preventive services; and for 20 percent of visits, at least three preventive services. Preventive counseling was provided during most (83 percent) visits that involved preventive services. Measurement of blood pressure was the most common type of physical examination recorded for visits during which preventive services were provided (28 percent); other physical examinations and laboratory measures were rare.

The adjusted and unadjusted odds ratios for receipt of preventive services are also listed in Table 1. The odds of receipt of preventive services were 1.45 times as high for visits to practices in rural areas as for visits to practices in metropolitan areas, although when the odds ratio was adjusted for potential confounding factors, the confidence interval included 1. The odds of preventive services were 2.5 times as high for visits for which diabetes, hypertension, or obesity was documented as for visits for which these chronic medical conditions were not recorded (adjusted odds ratio). Spending at least 30 minutes with the psychiatrist was also independently associated with receiving a preventive service compared with spending less than 30 minutes (adjusted odds ratio=1.8).

In a separate model we examined the subset of visits for which types of health care providers were documented. Visits that involved another type of provider—for example, a nurse or a medical assistant—had almost three times the odds of including a preventive service (OR=2.75, 95 percent confidence interval=1.66 to 4.57).

Certain variables were associated with lower odds of receiving a preventive service. For visits in health maintenance organizations, the adjusted odds of receiving a preventive service was less than half that for visits covered by private fee-for-service insurance. The adjusted odds of receiving a preventive service was almost 40 percent lower in the later part of the study period than in the period of 1992 to 1994.

Discussion and conclusions

In this random sample of visits to psychiatrists' offices by persons with severe mental illness in the 1990s, we identified characteristics associated with provision of clinical preventive medical services. Psychiatrists provided preventive services—principally counseling—during only 11 percent of visits by members of this vulnerable population.

Lifestyle counseling is especially indicated for the chronic medical conditions diabetes, obesity, and hypertension. It is reassuring that visits for which these high-risk conditions were documented were more likely to involve preventive services. However, it is possible that psychiatrists who were more likely to provide preventive services were also more likely to identify these chronic medical conditions. The higher frequency of preventive services for patients who saw another health provider in addition to the physician suggests that these services are more likely to be provided when the psychiatric office staff functions as a team. The higher odds of preventive services being provided by psychiatrists in rural areas than in metropolitan areas is consistent with the results of other studies, which have suggested that psychiatrists in rural practices serve an important primary care role for their patients with chronic mental illness (10).

The fact that preventive services were less likely to have been provided during visits in health maintenance organizations than during visits covered by private fee-for-service insurance could reflect greater administrative pressures in managed care settings and disincentives to provide services outside the traditional scope of psychiatry. However, this finding also is consistent with the fact that patients in health maintenance organizations have a primary care physician who is likely to be responsible for providing preventive care. The lower rate of provision of preventive services in the latter part of the study period, even after adjustment for payment source and visit length, could reflect increasing administrative pressures in psychiatric practice in the later part of the decade. This trend needs to be monitored carefully.

Although psychiatrists who provide care for patients with severe mental illness may not have sufficient time or training to deliver preventive medical services, they may facilitate receipt of preventive care by ensuring that their patients have access to primary care physicians, helping to coordinate care, and enhancing the quality of communication between patients and their primary care physicians. This detailed information about physicians' behavior is not available from the NAMCS.

The survey data have other limitations. Patients with severe mental illness may make multiple visits to a psychiatrist, but the visit-based design of the NAMCS does not allow for assessment of the amount of preventive services provided over time to an individual. In addition, we used diagnostic and medication codes to classify severe mental illness, but we did not have information on degree of impairment. Because the survey does not include visits to hospital outpatient departments or Department of Veterans Affairs medical facilities, our findings may not be generalizable to these settings.

This analysis showed that persons who have severe mental illnesses received clinical preventive medical services in a small minority of office visits to psychiatrists. Even during visits with characteristics associated with a greater likelihood of provision of preventive services, the rate of provision of these services was relatively low. The need for clinical preventive services, especially lifestyle counseling, in this population is high. More research on effective and practical solutions to ensure that people with severe mental illness receive appropriate preventive medical care is warranted.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by grant 1K08-MH-01787 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the School of Medicine and the Bloomberg School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University. Send correspondence to Dr. Daumit, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, 2024 East Monument Street, Suite 2-500, Baltimore, Maryland 21287 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue focusing on the health and health care of persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of patients and practice settings for psychiatric visits by patients with severe mental illness, frequency of preventive services, and odds of receiving general preventive services

1. Felker B, Yazel JJ, Short D: Mortality and medical comorbidity among psychiatric patients: a review. Psychiatric Services 47:1356-1363, 1996Link, Google Scholar

2. Prior P, Hassall C, Cross KW: Causes of death associated with psychiatric illness. Journal of Public Health Medicine 18:381-389, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kick SD, Morrison M, Kathol RG: Medical training in psychiatry residency: a proposed curriculum. General Hospital Psychiatry 19:259-273, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Shore JH: Psychiatry at a crossroad: our role in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1398-1403, 1996Link, Google Scholar

5. Carney CP, Yates WR, Goerdt CJ, et al: Psychiatrists' and internists' knowledge and attitudes about delivery of clinical preventive medical services. Psychiatric Services 49:1594-1600, 1998Link, Google Scholar

6. Golomb BA, Pyne JM, Wright B, et al: The role of psychiatrists in primary care of patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:766-773, 2000Link, Google Scholar

7. Dobscha SK, Ganzini L: A program for teaching psychiatric residents to provide integrated psychiatric and primary medical care. Psychiatric Services 52:1651-1653, 2001Link, Google Scholar

8. Cherry DK, Burt CW, Woodwell DA: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey:1999 summary. Advance data from Vital and Health Statistics, no 322. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 2001 Google Scholar

9. Korn EL, Graubard BI: Epidemiologic studies utilizing surveys: accounting for the sampling design. American Journal of Public Health 81:1166-1173, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Wagenfeld MO, Murray JD, Mohatt DF, et al: Mental health service delivery in rural areas: organizational and clinical issues. NIDA Research Monograph 168:418-437, 1997Medline, Google Scholar