Antipsychotic Drug Use Patterns and the Cost of Treating Schizophrenia

Abstract

This study investigated the relationships between antipsychotic drug use patterns and direct costs for 3,321 Medi-Cal patients with schizophrenia. Ordinary least-squares regression models were used to estimate the impact on costs of receiving antipsychotic drug treatment, delays in treatment, changes in therapy, and continuous therapy. Average costs were $25,940 per year per patient. Having used an antipsychotic drug was correlated with lower psychiatric hospital costs ($2,846 less) but higher nursing home costs. Completing one year of uninterrupted drug therapy was correlated with higher nursing home costs. Delayed drug treatment and changes in therapy increased the cost by $9,418 and $9,719, respectively.

Several second-generation antipsychotic medications with atypical symptom response and safety profiles show promise for enhanced tolerability; they have an improved efficacy profile for negative symptoms and appear to reduce use of health services (1,2,3). However, before accepting these products, cost-conscious buyers such as health maintenance organizations and state Medicaid programs require data that document the direct health care costs associated with schizophrenia and the extent to which conventional antipsychotic medications are not meeting the therapeutic needs of patients with schizophrenia.

This research, funded through a grant from Eli Lilly and Company, used data from Medi-Cal, the California Medicaid program, to investigate the effectiveness of conventional antipsychotic medications in real-world practice. Results documenting the antipsychotic drug use patterns of Medi-Cal patients reported previously (4) showed that more than 24 percent of study patients received no drug therapy for one year after their first recorded Medi-Cal service with a schizophrenia diagnosis. Furthermore, an additional 24 percent of patients treated with an antipsychotic medication within the first year began pharmacotherapy only after a delay of at least 30 days. Nearly half of all patients treated with an antipsychotic medication without a delay in pharmacotherapy switched therapies or augmented their initial therapy with a second antipsychotic medication during the year following the initiation of treatment. Finally, less than 12 percent of treated patients used an antipsychotic medication without interruption for one year. The purpose of this research was to investigate the relationship between these patterns of antipsychotic drug use and direct health care costs.

Methods

The data for the analysis were derived from Medi-Cal, which generates a longitudinal research database for a random 5 percent sample of all recipients (5). This database provides patient-level demographic data combined with a summary of each claim for covered services paid on behalf of the recipient. Data include type of service, date of service, amount billed, amount paid, and units (days) of service. Prescription drug claims identify the specific product dispensed, along with its quantity and strength and the date the prescription was filled. Data for this analysis were drawn from the period of January 1987 to July 1996.

Medi-Cal costs were partitioned by type of service for the purpose of estimating missing cost data for Medicare-covered services used by elderly and disabled Medi-Cal recipients who are eligible for both programs. Missing cost data for outpatient services were estimated for patients over age 65 on the basis of the amount paid by Medi-Cal and the Medicare part B deductible and coinsurance rate. Actual Medi-Cal expenditures for outpatient services were used for patients under 65 and for services not covered by Medicare part B, such as prescription drugs. All reported outpatient expenditures were adjusted to 1996 dollars using Medi-Cal-specific fee schedule adjustments.

Costs of care in hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and intermediate care facilities were estimated on the basis of the days of service recorded on the Medi-Cal paid claim. Days of care were multiplied by the average per diem cost reported for these services by Medi-Cal and Medicare: $979 per hospital day (6) and $270 per day of care in a skilled nursing or intermediate care facility (7). For simplicity and consistency, this method for pricing institutional services was applied to all patients regardless of age.

The methods used to define patient episodes of care, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the algorithms used to classify each patient's antipsychotic drug use pattern have been described elsewhere (4). However, the sample available for this cost analysis was expanded to include patients who were excluded from the previous sample because of illegible data in one or more of their paid claims; their illegible claims were deleted. This procedure substantially increased the number of patients in the sample.

In addition, new procedures were developed for reallocating to the place of service claims previously allocated to "other services," which resulted in a substantial increase in claims identified as acute hospital services. This more accurate accounting of direct costs by type of service also increased the sample available for the analysis.

Statistical methods

Ordinary least-squares models from the SAS Proc REG program (SAS version 6) were used to investigate the impact of antipsychotic drug use patterns on total health care cost and the components of total cost. Fifty-eight independent variables were included in these models. The variables included previous use of health care, demographic characteristics, mental and medical diagnostic mix, prescription drug profile, and antipsychotic drug use patterns. A dichotomous variable for having received drug treatment during the first year was entered directly into the cost models. The effects of delayed therapy, changes in therapy, and completed therapy were then measured using interaction terms between these drug treatment patterns and the dichotomous variable for having received drug therapy. In this way, each drug pattern effect was measured relative to other treated patients. For example, the estimated regression coefficient for the interaction term "treated × switched" measures the incremental costs associated with switching medications relative to the costs for treated patients who did not change drugs.

Results

The total direct cost of treatment for patients with schizophrenia was estimated to be $25,940 per year per patient. The major cost components were nursing home care (34.8 percent); ambulatory services, including services of psychologists and community mental health centers (27 percent); acute hospital care (23.3 percent); psychiatric hospital care (6.8 percent); and prescription drugs (3.7 percent).

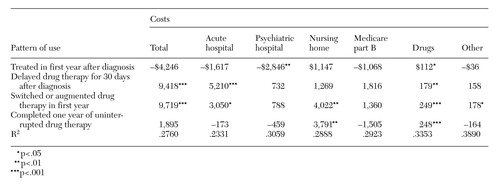

Table 1 presents the results of the regression models of total costs and costs by type of service. Only the estimate effects of the antipsychotic drug use patterns are reported due to space limitations (other results are available from the authors). Use of an antipsychotic drug in the first year after diagnosis was associated with lower psychiatric hospital costs (−$2,846, p<.01). Completing a year of uninterrupted use of an antipsychotic drug was associated with significantly higher nursing home costs of $3,791 (p=.004), which were somewhat offset by reductions in other costs.

The correlations between drug use and higher nursing home costs may reflect monitoring of compliance in the nursing home setting rather than drug use and compliant behavior resulting in higher nursing home costs. Delays in therapy and switches or augmentation of initial antipsychotic drug therapy in the first year were both associated with more than $9,000 in additional health care costs.

Discussion and conclusions

These data confirm results from earlier studies that concluded that the direct cost of treating schizophrenia represents a significant burden on the U.S. health care system (8,9). The cost to Medi-Cal of nearly $26,000 per patient per year compares with the costs reported in Massachusetts, which ranged between $15,000 and $19,000 in the 1991–1994 period (10). The annual direct cost estimate per patient found in California translates into a total direct cost of $49.1 billion for the U.S. health care system based on a 1 percent prevalence rate of schizophrenia and a U.S. adult population of 189 million in 1996.

This study documented the health care costs associated with antipsychotic drug use patterns of patients treated with conventional antipsychotic medications. Previous studies documented that conventional antipsychotic medications were not meeting the therapeutic needs of patients with schizophrenia treated in an outpatient setting (4). The analysis reported here documented that the use of conventional antipsychotics was not correlated with lower costs, even if the patient received uninterrupted drug therapy for one year. Furthermore, delays in treatment and changes in therapy were found to be associated with higher costs. Therefore, taken as a whole, a significant therapeutic need appears to exist for new antipsychotic therapies to treat patients with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

Dr. McCombs, Dr. Nichol, Mr. Shi, and Dr. Smith are with the department of pharmaceutical economics and policy in the School of Pharmacy at the University of Southern California, 1540 East Alcazar Street, Room CHP-140, Los Angeles, California 90089-9004 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Johnstone is with the health outcomes evaluation group of the U.S. Medical Division of Eli Lilly and Company in Indianapolis and the School for Public and Environmental Affairs at Indiana University in Bloomington. Dr. Stimmel is with the department of clinical pharmacy in the School of Pharmacy and the department of psychiatry in the School of Medicine at the University of Southern California.

|

Table 1. Results of multiple regression of variables associated with costs of treating 3,321 Medi-Cal patients with schizohrenia, by pattern of antipsychotic drug use

1. Lehman AF: Evaluating outcomes of treatments for persons with psychotic disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 11):61-67, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

2. Hargreaves WA, Shumway M: Pharmacoeconomics of antipsychotic drug therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 9):66-76, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

3. Glazer WM, Johnstone BM: Pharmacoeconomic evaluation of antipsychotic therapy for schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 58(suppl 10):50-54, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

4. McCombs JS, Nichol MB, Johnstone BM, et al: Use patterns for antipsychotic medications in Medicaid patients in California. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60(suppl 19):5-11, 1999Medline, Google Scholar

5. Medi-Cal Short Paid Claims Documentation. Sacramento, California Department of Health Services, Fiscal Forecasting and Data Management Branch, Medical Care Statistics Section, Aug 1997Google Scholar

6. California's Medical Assistance Program: Annual Statistical Report, Calendar Year 1994. Sacramento, California Department of Health Services, Medical Care Statistics Section, 1995Google Scholar

7. Health Care Financing Administration: Medicare and Medicaid statistical supplement. Health Care Financing Review 17:278, 1996Google Scholar

8. Rice DP, Miller LS: The economic burden of schizophrenia: conceptual and methodological issues and cost estimates, in Handbook of Mental Health Economics and Health Policy, vol. 1. Edited by Moscarelli M, Rupp A, Sartorius N. New York, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

9. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Leary MC, et al: An economic evaluation of schizophrenia, 1991. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 30:196-205, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dickey B, Normand ST, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a 4-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar