Medicaid Expenditures on Behavioral Health Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors reviewed studies of Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services. METHODS: Studies were identified through a search of MEDLINE and bibliographies of known articles on mental health and substance abuse spending and by searching Web sites of or contacting key government and private organizations. Of 448 studies identified, the 14 that included Medicaid expenditure percentages for 1984 or later were compared. RESULTS AND CONCLUSIONS: The most comprehensive studies of such spending suggest that between 9.3 and 13 percent of all Medicaid dollars are spent on behavioral health services. The most comprehensive estimates came from claims-based studies or studies based on the National Health Accounts. Studies based on provider or consumer surveys missed large portions of Medicaid spending. Policy makers need to ensure that they use the most accurate data to track mental health and substance abuse spending, an important part of total Medicaid expenditures.

Since 1996, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has sponsored a project to provide periodic estimates of national spending on mental health and substance abuse services. These estimates are designed to parallel the National Health Accounts produced by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

The most recent report from the SAMHSA project showed that total spending on behavioral health services in 1997 was $85 billion (1). Of this amount, 56 percent was from public sources. Medicaid was the largest single public payer, accounting for 35 percent of all public spending on mental health and substance abuse services. Only a small proportion of Medicaid expenditures on behavioral health services (14 percent) were devoted to substance abuse services.

Although the SAMHSA project aims to comprehensively estimate total spending on mental health and substance abuse services, achieving accuracy in Medicaid estimates is difficult. First, Medicaid is a heterogeneous program encompassing both federal policy and individual state decisions concerning eligibility as well as the scope and types of services. This heterogeneity is reflected in the design, quality, and completeness of individual state administrative databases for the program. Second, neither state Medicaid programs nor the CMS generally report program statistics by diagnosis. Thus routine information on expenditures on the treatment of mental disorders and substance abuse or other major conditions is not readily available.

The lack of routine program reporting on Medicaid mental health and substance abuse services means that available information comes from studies that rely on surveys of providers or consumers or analyses of state administrative claims. Each of these sources has its limitations. Consumer surveys are hindered by inaccuracy in recall of details of service use and by difficulty in reaching certain populations. Provider surveys may overlook nonspecialty sources of care. The size and complexity of Medicaid administrative data sets mean that their analysis can be expensive, so few such studies have been conducted. Until recently, Medicaid research files maintained by the CMS—and studies based on these files—were limited to four states. Figures derived from data from these four states may not generalize to other states given the variability in Medicaid programs from state to state.

Finally, regardless of data source, most Medicaid mental health and substance abuse studies have used different methodologies (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15). Spending on mental health and substance abuse services under Medicaid has been examined in the context of specific populations (such as children), for particular states, or under particular programs (such as behavioral carve-out programs), but research that looks at total Medicaid spending on behavioral health services has been limited (16,17).

Perhaps for these reasons, there has been no systematic effort to examine the literature on Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services and to understand possible differences in results between studies. We do not really know whether these studies generally converge in their findings on Medicaid expenditures on behavioral health services or, if they do not converge, the reasons for any divergence.

We identified and assessed all the studies of Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services that were conducted since 1984 and that analyzed survey or administrative program data. In this article we describe these studies and summarize their results. The study characteristics are evaluated in terms of their data sources, population coverage, service coverage, and geographic coverage. Finally, we discuss the degree of similarity in these studies and the extent to which different findings may be attributable to methodologic differences.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and bibliographies of known articles on mental health and substance abuse spending and explored Web sites of or contacted key government and private organizations: the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the U.S. General Accounting Office, the Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General, the Kaiser Family Foundation on Medicaid, the National Academy of State Health Policy, and the Urban Institute. We found 448 studies of Medicaid and mental health and substance abuse services. Of these, 14 studies included Medicaid expenditure information for 1984 or later. Because our study was a review of secondary data, we were not required to obtain institutional review board approval.

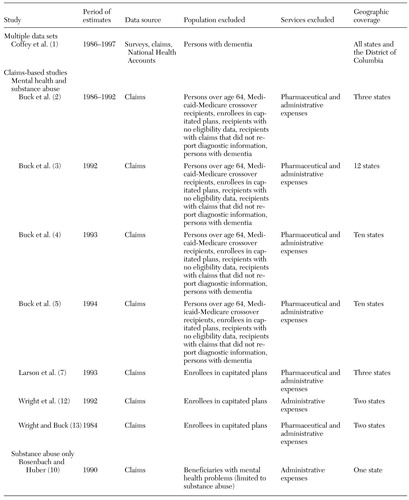

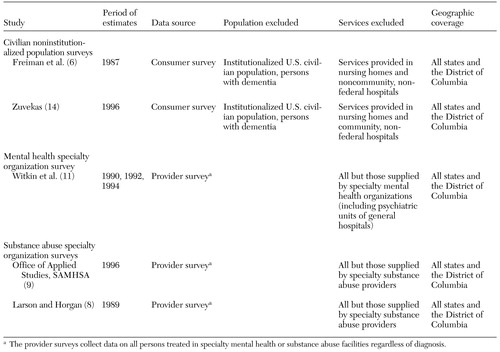

The 14 studies are listed in Tables 1 and 2, including the years covered by each, the type of data used, and the limitations in terms of populations excluded, services excluded, and geographic scope. To enable comparisons and to give the expenditures greater context, each expenditure figure is expressed as a percentage of total Medicaid spending for the relevant population (excluding administrative costs). When mental health and substance abuse spending was calculated as a proportion of total Medicaid spending for several states, spending on mental health and substance abuse services across those states was summed as the numerator and total Medicaid spending for those states for the appropriate year as reported by the study or the CMS was summed as the denominator. When possible, the same population was used for the denominator of total Medicaid expenditure as was used for the numerator. For example, both the numerator and the denominators in the studies by Buck and colleagues (2,3,4,5) exclude persons aged 65 years or older.

We excluded several studies that some readers might assume would have been included. A study by Frank and colleagues (15) projected the estimates for Medicaid spending reported by Wright and Buck (12) for 1984 to 1990. This projection indicates that Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services would have equaled 13.3 percent of total Medicaid expenditure in 1990. The projection of Frank and colleagues was not based on new data. Studies by Rice and colleagues (18) and the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (NASMHPD) (19) were also excluded. Rice and colleagues did not provide separate estimates of Medicaid expenditures on mental health and on substance abuse services. NASMHPD figures included only the component of Medicaid mental health and substance abuse expenditures that was administered by state mental health agencies. These figures reflect different administrative arrangements in each state and do not include sufficient information to determine the services or populations that the spending represents.

Results

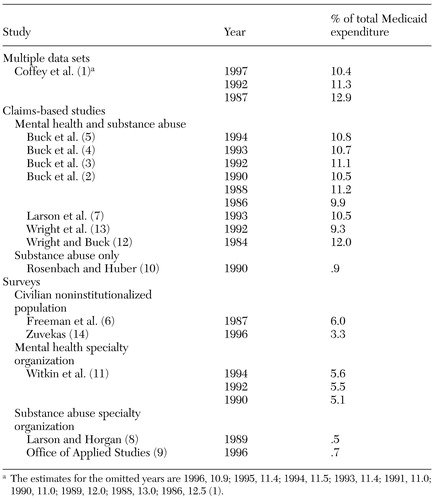

Medicaid spending on mental health services, substance abuse services, or both is summarized in Table 3 as a percentage of total Medicaid spending from each of the studies reviewed. Some studies produced more than one expenditure calculation. Therefore, there are more expenditure percentages listed in Table 3 than there are studies listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Multiple data sets and claims-based studies

Mental health and substance abuse services. Eight of the studies examined total Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services—one nationally and seven for selected states. The earliest calculation of mental health and substance expenditures was for 1984, and the latest was for 1997. Despite the differences in the studies' scope, years, and methods, they yielded relatively similar expenditure percentages. Mental health and substance abuse expenditures as a percentage of total Medicaid expenditures ranged from 9.3 percent to 12.9 percent. Seven of the eight studies used Medicaid claims from various states to calculate Medicaid spending. The other study, by Coffey and associates (1), used a variety of data sources to estimate Medicaid spending nationally and was the only study that purported to capture all Medicaid spending.

Buck and colleagues (2,3,4,5) conducted the most comprehensive of the Medicaid claims-based studies in terms of geographic coverage. They found that mental health and substance abuse expenditures as a percentage of total Medicaid expenditures were 9.9, 11.2, 10.5, 11.1, 10.7, and 10.8 in 1986, 1988, 1990, 1992, 1993, and 1994, respectively. Excluded populations were persons over the age of 64 years, Medicaid-Medicare crossover recipients, enrollees in capitated programs, recipients for whom there was no eligibility information, and recipients with claims that did not report diagnostic information. The total number of such enrollees excluded in 1993 was 647,538 out of 4.1 million, or 16 percent of the Medicaid population in the ten states. Persons were identified as having a behavioral health disorder if they had a primary mental health or substance abuse diagnosis or used specialty mental health or substance abuse services. Persons with dementia and mental retardation were excluded. Excluded services were prescription drug expenditures and administrative expenditures. Geographic coverage varied by years. Buck and colleagues (2,3,4,5) used Medicaid claims from three states in 1986, 1988, and 1990; 12 states in 1992; ten states in 1993; and ten states in 1994.

Using 1993 Medicaid claims, Larson and associates (7) found that Medicaid spending on behavioral health services was 10.5 percent of total Medicaid expenditure. These authors included all age groups as well as patients with dementia, but, as with all claims-based studies, they excluded persons enrolled in capitated plans. They also excluded spending on pharmaceuticals and administrative expenses. The data came from three states—Michigan, New Jersey, and Washington.

Wright and colleagues (12,13) examined behavioral health expenditures by using claims from Michigan and California for 1992 and 1984, respectively. They found that Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services was 9.3 percent and 12 percent, respectively, of total Medicaid expenditures. All age groups were included, although persons enrolled in capitated health plans who had no claims were excluded. One study (13) included prescription drug expenditures, whereas the other (12) did not. Neither study included administrative expenses. The main limitation of these studies was the limited geographic coverage. Specifically, the reason the former study (13) found that behavioral health expenditures represented only 9.3 percent of total Medicaid spending may be particular to the two states that the authors chose to examine. Studies that include a greater number of states tend to report higher expenditures for behavioral health services as a percentage of total Medicaid expenditure.

Substance abuse services only. One study used Medicaid claims to capture total spending on substance abuse treatment. Rosenbach and Huber (10) found that .9 percent of Medicaid spending was for substance abuse treatment in 1990. These authors used Medicaid claims data from the CMS's Medicaid Statistical Information System for Washington State to examine funding of drug abuse services. All types of services were included in the analysis, including long-term-care institutions, pharmaceutical expenditures, laboratory services, and physician services. The main limitation of the study was that it included only one state.

Coffey and colleagues (1) also estimated substance abuse spending as a percentage of total Medicaid expenditures. They found that substance abuse services accounted for 1.4 percent of Medicaid expenditures in 1992.

Surveys

Civilian noninstitutionalized population surveys. The studies by Freiman and colleagues (6) and Zuvekas (14) relied on consumer surveys to gather data on Medicaid behavioral health expenditures (6,14). Freiman and colleagues used the 1987 National Medical Expenditure Survey (NMES), and Zuvekas used the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) to provide national estimates of behavioral health expenditures in the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized population. The NMES and the MEPS are household surveys in which family members are questioned about their health care expenditures. The data are weighted to produce national estimates. As can be seen in Table 3, the estimates from the NMES survey (6 percent) and the MEPS survey (3.3 percent) are lower than those from studies that used claims or the National Health Accounts and provider surveys as their primary data sources.

In a recent study that compared the MEPS with the National Health Accounts (national estimates of total health care spending generated by the CMS), the MEPS estimate for total expenditures was $538 billion in 1996, whereas the NHA estimate was $912 billion (20). The results of that study highlight several reasons that the MEPS probably does not capture total Medicaid behavioral health spending. One limitation is the population covered. Active-duty military personnel were excluded from the MEPS and the NMES, as were persons in nursing homes, intermediate care facilities for persons with mental retardation, other long-term-care facilities, and prisons. In addition, because the MEPS and the NMES are household surveys, they may have difficulty reaching certain populations that have unstable housing. A second limitation of the MEPS and the NMES is the services excluded—specifically, noncommunity, nonfederal hospitals such as psychiatric hospitals that provide long-term care and nursing homes. Finally, health services delivered in nonhealth settings, such as schools and at home, are probably outside the scope of the MEPS.

Mental health specialty organization survey. Witkin and colleagues (11) assessed Medicaid spending in specialty mental health organizations by using data from the Inventory of Mental Health Organizations (IMHO) (11). The IMHO is a biennial survey of specialty mental health organizations, including psychiatric hospitals, specialty psychiatric units of general hospitals, mental health clinics, and residential treatment centers.

The IMHO reports Medicaid revenues in specialty mental health facilities. The expenditure percentages are lower than those from studies that capture total Medicaid spending on the basis of claims data or other methods. The expenditure percentages were 5.1 percent, 5.5 percent, and 5.6 percent in 1990, 1992, and 1994, respectively.

The main limitation of the IMHO—and the main reason estimates from the IMHO are lower than other estimates—relates to the services and providers covered. The IMHO does not capture expenditures by independent practitioners, such as psychiatrists and social workers; expenditures on care delivered in nonspecialty settings, such as nonspecialty units of general hospitals and nursing homes; prescription drug spending; or spending on substance abuse treatment, except that provided in psychiatric facilities.

Substance abuse specialty organization surveys. Two studies examined Medicaid spending on substance abuse treatment in specialty facilities. The results of these studies suggest that such spending represents a small proportion of total Medicaid spending, ranging from .5 to 1.3 percent.

The studies by Larson and Horgan (8) and the Office of Applied Studies (9) both used the Uniform Facility Data Set (UFDS) to develop expenditure calculations. The UFDS is a survey of specialty substance abuse treatment providers conducted annually by SAMHSA. Medicaid spending was assessed by asking providers to report total revenues and to indicate the proportions attributable to various payers. The main limitation of the UFDS-based studies is the limited number of services and providers they capture. The calculations of Larson and Horgan and the Office of Applied Studies did not adjust for nonresponse, so not all substance abuse facilities were captured. Furthermore, these studies did not capture prescription medications or services provided by nonspecialty providers. Thus the Medicaid expenditures reported understate the true magnitude of Medicaid funding.

Discussion and conclusions

More than 40 million Americans are enrolled in Medicaid (21). Mental health and substance abuse policy makers need to know how much of Medicaid funding is being allocated to behavioral health services. This information is available from a variety of sources. However, most data users may not know which sources are the most comprehensive and what is included and excluded. Our goal was to provide a comprehensive review of studies of Medicaid behavioral health spending to highlight the strengths and limitations of various approaches.

Our review indicated that the most comprehensive studies provide a relatively narrow range of calculations of Medicaid behavioral health spending. Mental health and substance abuse services accounted for between 9.3 percent and 13 percent of total Medicaid spending between 1984 and 1997. Thus one can say with relative confidence that about one in ten Medicaid dollars goes to mental health and substance abuse services. However, it should be noted that this proportion reflects Medicaid spending for covered services only and that Medicaid beneficiaries may use behavioral health services that are not covered by Medicaid.

One useful point of departure for appreciating Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services is private health insurance spending on these services. Studies indicate that behavioral health services account for between 3.1 and 5.6 percent of total private health insurance claims (1,22). The larger proportion of Medicaid behavioral health spending reflects the fact that Medicaid offers a more generous benefit package for mental health and substance abuse services, with minimal cost sharing. Moreover, Medicaid enrollees include persons with disabilities, who are more intensive users of services. Finally, Medicaid enrolls young adults, who also have an elevated risk of behavioral health problems.

One implication of the relatively large proportion of Medicaid spending on mental health and substance abuse services is the importance of tracking the cost and quality of such services. Over the past year, Medicaid programs have faced tremendous fiscal pressures. As a result of soaring costs and declining state revenues, state legislatures are looking for ways to cut benefits and reduce payments to providers (23). Tracking mental health and substance abuse spending is one way to understand the tradeoffs that states are making among benefits and services.

In contrast with total behavioral health expenditures, substance abuse expenditures account for a small proportion of Medicaid claims—less than 2 percent. Studies of substance abuse spending as a percentage of private insurance have found even lower percentages: .8 and .4 percent (1,24). Substance abuse and dependence are common disorders, affecting 16 percent of the adult population in a given year (25,26). The gap between the prevalence of substance use disorders and the percentage of treatment expenditures suggests that most people with a substance use disorder are not being treated for it in the formal treatment system under reimbursed insurance. This reality may partly reflect the relatively poor coverage of substance abuse treatment under Medicaid and private insurance. It may also reflect a preference for treatment in informal and free settings, such as Alcoholics Anonymous. In addition, social stigma as well as a belief that people can end substance abuse on their own may prevent individuals from seeking formal treatment.

The studies we reviewed calculated Medicaid spending on behavioral health services by using four basic methods. These methods have advantages and disadvantages that should be understood by users. One method involves the use of Medicaid claims to calculate Medicaid spending in particular states. The main advantage of Medicaid claims data is that they capture most services and consumers. The main disadvantage is that claims are not available in all states. Also, data from managed care plans, which do not generate claims, often do not provide spending data.

A second methodology involves using the National Health Account estimates of Medicaid spending as a base and then using various databases to carve out the proportion of Medicaid spending allocated to mental health and substance abuse services. This approach is limited by the accuracy of a number of different surveys to allocate mental health and substance abuse spending but has the advantage of being tied to the National Health Accounts, which provide a very accurate picture of total Medicaid expenditures.

The other two approaches rely on provider surveys and consumer surveys. The IMHO and the UFDS are the main mental health and substance abuse provider surveys, and the NMES and the MEPS are the main consumer surveys. We found that consumer surveys and provider surveys may miss as much as half of Medicaid mental health and substance abuse spending. Provider surveys leave out the general service sector, such as physicians, prescription drugs, and nonspecialty beds in general hospitals. In 1997, some 30 percent of national behavioral health spending went to general providers and prescription medications (1). The NMES and the MEPS are household-based surveys and thus miss institutionalized individuals and some services.

In conclusion, policy makers need good data on what Medicaid spends on mental health and substance abuse treatment. This review aimed to answer this question and to help consumers of data on Medicaid mental health and substance abuse spending sort through the various data sources and understand how they can and cannot be used.

Acknowledgment

Preparation of this article was funded by contract 270-96-0007 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and the Center for Mental Health Services of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Dr. Mark and Dr. Coffey are affiliated with the Medstat Group, 4301 Connecticut Avenue, Suite 330, Washington, DC 20008 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Buck is with the Center for Mental Health Services and Dr. Dilonardo and Dr. Chalk with the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration in Rockville, Maryland.

|

Table 1. Studies of Medicaid expenditures on mental health and substance abuse services, multiple data sets and claims data

|

Table 2. Studies of Medicaid expenditures on mental health and substance abuse services, survey data

|

Table 3. Expenditures on mental health and substance abuse services as a percentage of total Medicaid spending from various studies for indicated years

1. Coffey RM, Mark TL, King E, et al: National Expenditures for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. Pub (SMA) 00-3499. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Center for Mental Health Services, July 2000Google Scholar

2. Buck JA, Miller K, Bae J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid, 1986-1992. Publication (SMA) 99-3366. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2000Google Scholar

3. Buck J, Miller K, Bae J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid, 1992. Publication (SMA) 99-33678. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2000Google Scholar

4. Buck J, Miller K, Bae J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid, 1993. Publication (SMA) 99-3368. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2000Google Scholar

5. Buck JA, Miller K, Bae J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services in Medicaid, 1994. Publication (SMA) 00-3284. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2000Google Scholar

6. Freiman MP, Cunningham W, Cornelius L: Use and Expenditures for the Treatment of Mental Health Problems: National Medical Expenditure Survey Research Findings 22. Publication 94-0085. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, July 1994Google Scholar

7. Larson MJ, Farrelly MC, Hodgkin D, et al: Payments and use of services for mental health, alcohol, and other drug abuse disorders: estimates from Medicare, Medicaid, and private health plans, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. Edited by Manderscheid R, Henderson M. Publication (SMA) 99-3285. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998Google Scholar

8. Larson MJ, Horgan CM: Variations in state Medicaid program expenditures for substance abuse units and facilities, in Services Research Monograph: Financing Drug Treatment Through State Programs. Edited by Denmead G, Rouse BA. Publication 94-3542. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1994Google Scholar

9. Uniform Facility Data Set (UFDS): Data for 1996 and 1980-1996. Publication (SMA) 98-3176. Rockville, Md, Office of Applied Studies, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 1998Google Scholar

10. Rosenbach ML, Huber JH: Utilization and cost of drug abuse treatment under Medicaid: an in-depth study of Washington State, in Services Research Monograph: Financing Drug Treatment Through State Programs. Edited by Denmead G, Rouse BA. Publication 94-3542. Bethesda, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1994Google Scholar

11. Witkin MJ, Atay JE, Manderscheid RW, et al: Highlights of organized mental health services in 1994 and major national and state trends, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. Publication (SMA) 99-3285. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

12. Wright GE, Buck JA: Medicaid support of alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health services. Health Care Financing Review 13:117-127, 1991Medline, Google Scholar

13. Wright G, Smolkin S, Bencio D: Medicaid Mental Health and Substance Abuse 1992: Use and Expenditure Estimates for Michigan and California: Final Report. Washington, DC, Mathematica Policy Research, 1995Google Scholar

14. Zuvekas SH: Trends in Mental Health Services Use and Spending, 1987-1996. Health Affairs 20(2):214-224, 2001Google Scholar

15. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Regier DA, et al: Payment for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Care. Health Affairs 13(1)337-342, 1994Google Scholar

16. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

17. Buck JA: Utilization of Medicaid mental health services by nondisabled children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services 48:65-70, 1997Link, Google Scholar

18. Rice DP, Kelman S, Miller LS, et al: The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness:1985. San Francisco, Institute for Health and Aging, University of California, 1990Google Scholar

19. Funding Sources and Expenditures of State Mental Health Agencies: Fiscal Year 1997: Final Report. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute, July 1999Google Scholar

20. Selden TM, Levit KR, Cohen JW, et al: Reconciling medical expenditure estimates from the MEPS and the NHA, 1996. Health Care Financing Review 23:161-178, 2001Medline, Google Scholar

21. Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Policy: Medicaid Beneficiaries, Vender, Medical Assistance, and Administrative Payments. Available at http://www.hcfa.gov/medicaid/msis/2082-1.htmGoogle Scholar

22. Health Care Plan Design and Cost Trends:1988 through 1997. Hay Group Management, Inc. Prepared for the National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, the Association of Behavioral Group Practices, and the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, May 1988Google Scholar

23. Pear R, Toner R: Amid Fiscal Crisis, Medicaid Is Facing Cuts From States. New York Times, Jan 14, 2002, A1Google Scholar

24. Schoenbaum M, Zhang W, Sturm R: Costs and utilization of substance abuse care in a privately insured population under managed care. Psychiatric Services 49:1573-1578, 1998Link, Google Scholar

25. Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry 51:8-19, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Summary of Findings From the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available at www.samhsa.gov/news/click3_frame.htmlGoogle Scholar