Costs and Utilization of Substance Abuse Care in a Privately Insured Population Under Managed Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Cost and utilization patterns of substance abuse and mental health treatment under private, employer-sponsored, managed behavioral health care plans were examined. METHODS: Data were from claims made in 1995 in 93 behavioral health care plans covering 617,133 members. Rates of use of mental health and substance abuse care were determined, as were payments by insurers and patients for the two types of care. Means were calculated per plan member and per user of either of these service types. RESULTS: Approximately .3 percent of plan members used any substance abuse services; 5.2 percent used mental health services. However, among substance abuse patients, average costs were more than twice as high as average costs for mental health patients. For substance abuse treatment, the annual cost per user was $2,188, compared with $979 for users of mental health care. Annual per-member costs were $6.51 for substance abuse treatment and $50.08 for mental health care. Higher costs for substance abuse treatment reflected greater rates of use of both inpatient and intensive outpatient treatment. Overall, substance abuse costs represented 13 percent of insurance payments for behavioral health care and perhaps .4 percent of the cost of health insurance overall. CONCLUSIONS: Substance abuse coverage accounts for a small fraction of insurance payments for behavioral health coverage and a very small fraction of insurance payments for both physical and behavioral health care.

Behavioral health care has changed dramatically in recent years with the growth of managed care. A particularly important type of managed care is a carve-out, in which mental health and substance abuse care are administered separately from medical care. Carve-out arrangements have increased rapidly, almost doubling their enrollment between 1992 and 1997—from 78 million to 150 million Americans; they now cover almost 75 percent of people with private health insurance (1).

At the same time, managed behavioral health care itself has been changing from primary care gatekeeping and prospective payments under health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to intensive concurrent utilization review of specialty care under carve-outs. Indeed, the changes for behavioral health care in the private sector have arguably been more dramatic than the corresponding changes in the general medical sector.

These market changes happened very fast, in many ways too fast for research to keep up. For example, a 1998 study commissioned by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration assumes that patterns of behavioral health care in HMOs and carve-outs are equivalent and that indemnity plans, preferred provider plans, point-of-service plans, and HMOs each have a 20 to 30 percent share of the behavioral health market (2). Neither assumption is currently realistic (1,3).

The lack of current data on costs and use is especially acute with respect to substance abuse treatment. Most employer-sponsored health insurance plans include some substance abuse benefits (4), although benefits are more limited than for other illnesses (4,5). Despite recognition of the importance of studying substance abuse treatment using large administrative datasets of claims and utilization data (6), researchers have had limited success obtaining such data from private companies. Most existing research has been confined to public programs (7) or to case studies of a small number of employers (8,9).

More recent studies using large administrative databases analyzed substance abuse and mental health care together, but because costs for mental health care are so much larger, these studies provided little information about costs for substance abuse care (10,11,12,13,14,15). As a result, we know little about how new institutional arrangements and practice patterns affect substance abuse care.

This paper describes 1995 cost and utilization patterns for substance abuse treatment under managed behavioral health care insurance. We examined the experience of members of private, employer-sponsored, managed care carve-out programs run by United Behavioral Health (UBH), the third largest managed behavioral health care company in the U.S. Using a sample of large plans administered by UBH, we determined average costs per member, average costs per user, and use rates for mental health care and for substance abuse care. We also examined alcohol treatment and drug treatment costs separately.

Up-to-date information on costs and use of substance abuse benefits may be important for several reasons. The lack of current data on costs and use for both substance abuse and mental health benefits has significantly inhibited efforts at behavioral health insurance reform (16), and uncertainty about the costs of substance abuse treatment has often led policy makers to exclude substance abuse care from reform proposals entirely (17).

Furthermore, although most employer-sponsored health insurance plans, including behavioral health carve-outs, administer mental health and substance abuse benefits jointly, recent legal mandates covering mental health but not substance abuse treatment could increase the separation between mental health and substance abuse care in health insurance (4). Such separation is especially problematic for people with comorbid mental health and substance abuse disorders, estimated to include more than half of drug abusers (18). Finally, cost-conscious employers basing decisions on older data might offer different levels of substance abuse benefits than they would if they had more current information.

Methods

Our database consisted of administrative records from behavioral health plans administered by UBH, including information on benefit design, health service use and costs, characteristics of members (employees and their dependents), and characteristics of participating medical providers. To ensure anonymity, all identifying information about members and providers was removed from the data provided by UBH.

For this analysis, we selected 93 employer-sponsored plans for which we could identify the population at risk rather than just those who used services. This dataset covered a total of 617,133 members from 37 different employers. Some employers had multiple plans for operations in different geographical areas or for different types of employees. We view this dataset as representing a population and do not seek to generalize our findings to other UBH members or to people with other types of insurance.

The dataset covered employees in a wide range of industries and all 50 states; California and several Midwestern states were overrepresented. Gender and education distributions were similar to those in the overall U.S. population, while the prevalence of ethnic minorities was slightly higher in the UBH sample. Median family income was $11,900 higher than the U.S. median in 1995, presumably because UBH plans are employer sponsored.

The plans covered a full range of behavioral health treatment services: acute inpatient hospitalization and detoxification, residential treatment, intermediate services (recovery homes, structured outpatient care, and day care), and standard outpatient therapy. This range of services reflects a significant change from the past, under both unmanaged indemnity care and HMOs, in which residential care and intermediate services were rarely covered or available. The full range of services requires preauthorization and is available only through network providers. About half the members in our sample also had some, more limited coverage for unmanaged services out of network, usually with higher out-of-pocket costs.

In this study we examined total costs for all services delivered during calendar year 1995, including both insurance payments and patient payments. Insurance payments also included payments made by insurance carriers other than UBH through coordination of benefits. We note that insurance payments do not equal charges because providers can bill amounts other than they have contractually negotiated; also, payments do not necessarily reflect the true resource costs of providing a specific service, which could be higher or lower. Patient payments included copayments (a fixed dollar amount, most common for network services) or coinsurance (a percentage of charges, most common for nonnetwork benefits), deductibles (usually only for nonnetwork use), and penalties (only for unauthorized services).

We classified separate costs for mental health or substance abuse according to the primary DSM-IV diagnosis on each individual claim. We recognize that a claim might carry a mental health diagnosis and nevertheless be for substance abuse treatment, or vice versa. However, such discrepancies were rare in these data. For example, among treatments authorized and classified by care managers as mental health treatments, only 1 percent were for patients with diagnoses of substance use disorders but not mental disorders; even such cases were not necessarily mistakes, since patients may have received a mental health diagnosis before the study period.

Our dataset included only behavioral health care; medical care and pharmaceuticals were excluded. Of 163,365 claims, 2,974 (1.8 percent) could not be classified because diagnoses were missing or outside the DSM range, primarily due to administrative errors, such as submitting dental claims to UBH. Payments associated with those claims were negligible and did not affect our results.

Except where noted, all calculations were done by pooling all members in all plans and calculating simple means for this population or for specified subgroups.

Results

Plan characteristics

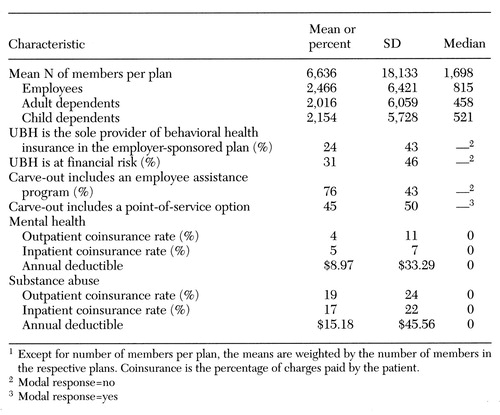

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the plans covered in this analysis. The plans varied widely in size but typically included at least several thousand people, divided almost equally between employees, adult dependents, and child dependents.

All means in Table 1 are weighted by the number of members in the respective plans. For 24 percent of the members in our study, the UBH plan was the sole provider of behavioral health insurance coverage for their employer, regardless of the source of physical health insurance. The remaining employees could choose an insurance package that included behavioral health insurance from UBH, but their employer offered them at least one alternative insurance package for which behavioral health benefits were not administered by UBH.

Contractual arrangements between UBH and the employers varied. Thirty-one percent of members in this study were covered by plans in which UBH acted as insurer as well as administrator and was at full financial risk; the rest were covered by plans in which employers paid UBH a fixed administrative fee to manage the behavioral health carve-out program, but UBH passed the costs for actual claims to the employer. For 76 percent of members in this sample, an employee assistance program (EAP) was integrated into the behavioral health carve-out. EAPs provide an important pathway into care, especially for substance abuse, and we included substance abuse payments in our calculations. The costs of EAPs themselves are relatively minor, because EAP benefits are restricted to a small number of outpatient sessions; three to five visits is a common restriction. In plans that integrate EAPs with care management, there is a seamless transition from EAP benefits into insurance benefits.

Under all UBH plans, network health care providers are paid via a fee-for-service arrangement, based on national negotiated rates. However, 45 percent of the members in our sample were covered by plans that included a point-of-service option, which permitted members to seek care outside of the plan's network of health care providers. Such nonnetwork claims were included in our cost calculations, but they tended to account for a small percentage of costs (5 to 10 percent).

Finally, the table presents information on coinsurance rates (the fraction of treatment costs that patients pay themselves) and annual deductibles for mental health and substance abuse care. The table shows that the typical member faced a higher out-of-pocket financial burden for substance abuse than for mental health (and that coinsurance rates can be substantial). At the same time, many plans in the study had quite low levels of coinsurance and deductibles, and the median copayment and deductible in these plans was zero for both mental health and substance abuse care.

Health service use and costs

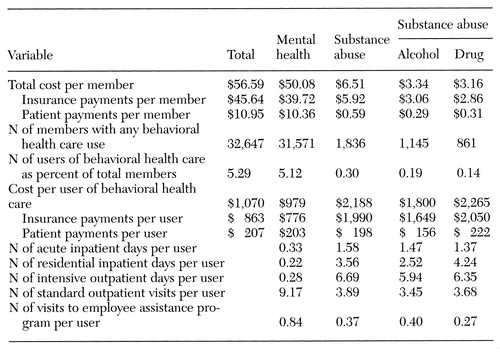

Of the 617,133 members in our dataset, about 5 percent (32,647 members) used any behavioral health care, and 94 percent of the users (30,811 members) received only mental health care. About 3 percent of the behavioral health users (1,076 members) had only substance abuse claims, while 2 percent (760 members) had both. Among patients with only substance abuse claims, 57 percent (614 members) received care for alcohol use only, 35 percent (376 members) for drug abuse only, and 8 percent (86 members) for both.

In contrast, among the 760 patients with both mental health and substance abuse claims, 48 percent (361 members) had claims for alcohol but not drug abuse, 41 percent (315 members) for drug abuse only, and 11 percent (84 members) for both.

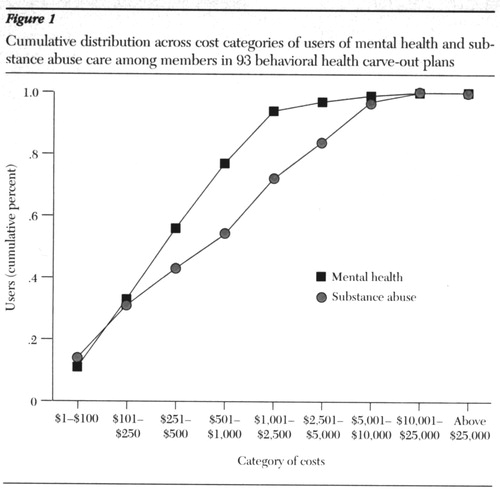

Table 2 presents mean costs and utilization for behavioral health care overall and by type of treatment. For both treatment types, the table presents mean costs per member, as well as insurance payments and out-of-pocket costs. The table also lists the number and fraction of members using the service type. In contrast to the categories in Figure 1, the categories in Table 2 are not mutually exclusive; that is, a patient with substance abuse and mental health claims would appear in both columns of the table. However, costs are divided according to individual claims.

Substance abuse treatment accounted for approximately 12 percent of the overall costs of behavioral health care in this sample, which was calculated by dividing the overall cost per member ($56.59) by the cost per member for substance abuse care ($6.51). Substance abuse care accounted for approximately 13 percent of overall insurance payments, which was calculated by dividing the member cost for insurance payments ($45.64) by the cost of insurance for substance abuse care ($5.92).

However, patient payments for substance abuse care accounted for only about 5 percent of patient payments per member ($10.95 divided by $.59), despite lower benefits for substance abuse treatment. Costs for substance abuse care were approximately evenly distributed between alcohol and drug treatment.

Although just over 5 percent of members used at least some mental health benefits, only .3 percent used substance abuse benefits. However, costs per user were twice as high for substance abuse as for mental health. On average, the treatment received for alcohol use cost $1,800 per user, and the treatment received for drug use cost $2,265, compared with $979 per user for mental health treatment. Correspondingly, users of alcohol and drug treatment received an average of 5.1 days of inpatient care and 6.7 days of intensive outpatient care, cost-intensive services that mental health patients hardly used.

Figure 1 presents the cumulative distribution of members across cost categories and confirms that patterns of use were different for substance abuse and mental health care. The figure shows that a large proportion of mental health care users incurred relatively low costs, while users of substance abuse treatment were more uniformly distributed across cost categories. For instance, 56 percent of mental health care users incurred less than $500 in costs, compared with 43 percent of users of substance abuse treatment. Similarly, 77 percent of mental health care users and 54 percent of users of substance abuse treatment had costs below $1,000, and 94 percent of mental health users and just 72 percent of substance abuse users had treatment costs below $2,500.

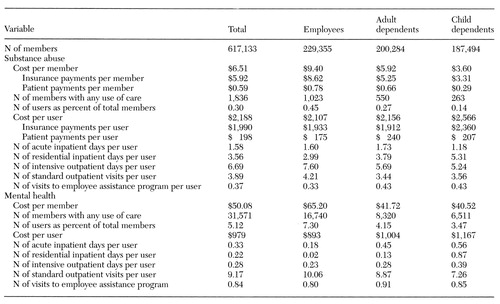

Table 3 presents cost and utilization data by type of member and by type of care. With respect to substance abuse treatment, employees were more likely than adult dependents or children to have used substance abuse benefits and to have incurred higher costs per member. However, employees had the lowest costs per user, and child dependents the highest; mean costs for children were $427 higher per user than costs for employees.

Patterns of use differed too. On average, employees had a relatively higher use rate for outpatient care, whereas dependents used inpatient care at a higher rate.

Table 3 also shows similar patterns for mental health treatment. Employees were more likely than adult dependents or children to use any mental health care, and they also had higher costs per capita. However, on a per-user basis, employees were again the least expensive, and child dependents the most. Patterns of inpatient and outpatient use also mirrored those observed for substance abuse care.

Discussion

We have documented 1995 cost and utilization patterns for substance abuse and mental health treatment under private, employer-sponsored, managed behavioral health carve-out plans run by one firm. Across these plans, we found that 17 times as many members used mental health services than substance abuse services, and that costs for substance abuse treatment represented 13 percent of overall insurance payments for behavioral health insurance.

Because our data covered behavioral health care, we do not know the actual cost of physical health insurance provided to the members in our sample. However, the typical annual per-member cost of private HMO coverage for an employed population has been estimated to be $1,356 (19). If so, overall behavioral health insurance payments represent 4 percent of the total cost of providing health insurance—calculated by dividing the total cost per member for behavioral health care ($56.59) by the total costs for physical and behavioral health care ($1,356 + $56.59 = $1,412.59). Substance abuse coverage ($6.51 per member per year) represents .5 percent of the total cost of health insurance ($6.51÷$1,412.59).

When offered in combination with indemnity insurance or a preferred provider network, which have higher annual insurance costs than HMOs, the typical UBH carve-out represents an even smaller fraction of the total cost of providing health insurance. Therefore, even substantial changes in substance abuse benefits would probably have little effect on total insurance payments for health care.

With respect to costs per user, we found that average costs among people who received substance abuse treatment were more than twice as high as average costs among people who received mental health treatment. From an economic perspective, these differences are apparently due to the much greater reliance on inpatient and intermediate care observed for substance abuse. It is worth emphasizing that this relatively high rate of use of inpatient care for substance abuse is occurring in the same types of managed care carve-out plans that have been associated with significant shifts from inpatient to outpatient mental health care (20). Although the continued high rate of inpatient care for substance abuse reflects current practice patterns, it thus also reflects differences between mental and substance use disorders. Shifts over time in practice patterns for substance abuse care should be the focus of future research.

To control the costs of providing behavioral health insurance, nearly all mental health and substance abuse plans include some limits on the types or quantities of services for which members are eligible (4). Due to the very large number of different types of limits among UBH plans (4), summarizing the limits of the plans in our sample is beyond the scope of this study. However, our main findings on use and costs of substance abuse treatment do not appear to be driven by restrictive benefit limits. For instance, in an exploratory analysis of a subset of plans identified as having particularly generous benefits, our substantive findings were very similar. The effects of substance abuse treatment limits should be a subject for future research. (Further information on benefit limits in the plans in this study are available from the authors.)

We note a number of limitations in this research. For instance, we had data only from carve-out plans run by one firm, and the experience of other providers may be different. However, although UBH plans share some important common features, they are also heterogeneous in many dimensions. We intend to use this heterogeneity to understand the operation of substance abuse plans in more detail in the future. Future research should also compare substance abuse coverage in carve-out plans with coverage provided by other types of insurance.

In addition, the employers in our study chose to offer behavioral health insurance via a carve-out and to contract with UBH directly. As a result, they may not be representative of other employers. However, the UBH data include a wide variety of employers, and members appear demographically similar to the overall employed population. Comparison with nonemployed groups is beyond the scope of this work but should also be the subject of future research.

Finally, we cannot assess the extent to which the care received by the members in our dataset was effective. However, out-of-network use in plans with a point-of-service option was quite low. Because the point-of-service option can be viewed as an outlet if members are dissatisfied with network care, its low use in these plans may be a positive sign. Analysis of health outcomes is beyond the scope of this work, but it is critical for examining broader issues such as the cost-effectiveness of care.

Conclusions

We view this study as a baseline description of utilization of substance abuse treatment under managed care carve-out plans, a major and increasingly prevalent form of insurance for substance abuse care. According to our data, substance abuse coverage accounts for a small fraction—13 percent—of insurance payments for behavioral health coverage, and a very small fraction—probably less than half a percent—of total insurance payments for physical and behavioral health insurance.

Because insurance payments represent the cost to employers of providing insurance benefits, they are the most relevant cost measure for employers to use in making benefit decisions. They are also the most relevant measure for policy decisions about coverage mandates on employers or insurers. Our results provide relatively current data to inform such decisions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to United Behavioral Health, and especially to William Goldman, M.D., and Joyce McCulloch, M.S., for their help. Financial support was provided by grants MH54147 and MH54623 from the National Institute of Mental Health, by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and by grant DA11832 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The authors are affiliated with the Rand Corporation, 1700 Main Street, Santa Monica, California 90407 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

Figure 1. Cumulative distribution across cost categories of users of mental health and substance abuse care among members in 93 behavioral health carve-out plans

|

Table 1. Characteristics of 93 carve-out behavioral health plans operated by United Behavioral Health (UBH)1

|

Table 2. Mean cost and use of mental health and substance abuse care by 617,133 members in 93 behavioral health carve-out plans in 1995

|

Table 3. Mean cost and use of substance abuse and mental health care by 617,133 members in 93 behavioral health carve-out plans in 1995, by type of enrollee

1. Oss ME, Drissel AB, Clary J: Managed Behavioral Health Market Share in the United States, 1997-1998. Gettysburg, Penn, Behavioral Health Industry News, 1997Google Scholar

2. Sing M, Hill S, Smolkin S, et al: The Costs and Effects of Parity for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Insurance Benefits. DHHS publication 98-3205. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1998Google Scholar

3. Sturm R, Goldman W, McCulloch J: Mental Health and Substance Abuse Parity: A Case Study of Ohio's State Employee Program. Working paper 128. University of California, Los Angeles, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1998Google Scholar

4. Sturm R, McCulloch J: Mental health and substance abuse benefits in carve-out plans and the Mental Health Parity Act of 1996. Journal of Health Care Finance 24(3):84-95, 1998Google Scholar

5. Health Care Plan Design and Cost Trends:1988 through 1997. Washington, DC, Hay Group, 1998Google Scholar

6. McGuire TG, Shatkin, BF: Forecasting the cost of drug abuse treatment coverage in private health insurance, in Economic Costs, Cost-Effectiveness, Financing, and Community-Based Drug Treatment. Edited by Cartwright WS, Kaple JM. NIDA research monograph 113. Rockville, Md, National Institute on Drug Abuse, 1991Google Scholar

7. Cartwright WS, Ingster L: A patient-based analysis of drug disorder diagnosis on length of stay and total charges for the Medicare population. Health Care Financing Review 15(2):89-101, 1993Google Scholar

8. Holder HD, Blose JO: Alcoholism treatment and total health care utilization and costs. JAMA 256:1456-1460, 1986Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Holder HD, Blose JO: Reduction of health care costs associated with alcoholism treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 53:293-302, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sturm R: How expensive is unlimited mental health care coverage under managed care? JAMA 278:1533-1537, 1997Google Scholar

11. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

12. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a mental health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

13. Gresenz CR, Liu X, Sturm R: Managed behavioral health services for children under carve-out contracts. Psychiatric Services 49:1054-1058, 1998Link, Google Scholar

14. Sturm R: How Does Risk Sharing Between Employers and Managed Behavioral Health Organizations Affect Health Care? Working paper 113. University of California, Los Angeles, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

15. Gresenz CR: Utilization and Costs of Managed Mental Health Care: The Effects of Selection Into Plan and Employer. Working paper 114. University of California, Los Angeles, Research Center on Managed Care for Psychiatric Disorders, 1997Google Scholar

16. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Estimating costs of mental health and substance abuse coverage. Health Affairs 14(3):102-115, 1995Google Scholar

17. Frank RG, Koyanagi C, McGuire TG: The politics and economics of mental health parity laws. Health Affairs 16(4):108-119, 1997Google Scholar

18. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Melek SP, Pyenson B: Premium Rate Estimates for a Mental Illness Parity Provision to S. 1028: The Health Insurance Reform Act of 1995. Denver, Milliman & Robertson, 1996Google Scholar

20. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and utilization of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar