Health Behaviors and Health Status of Older Women With Schizophrenia

Abstract

The authors interviewed 43 women with schizophrenia who were 40 to 70 years of age about their health status, preventive health care, addictive behaviors, and comorbid medical conditions. Data were compared with those for age-matched samples from the general population. Thirty women in the study sample (71 percent) were overweight or obese, compared with 38 percent in the general population. Twenty-seven (63 percent) smoked cigarettes. Twenty-six women (62 percent) had received a mammogram in the past two years, compared with 86 percent in the general population. Rates of routine physical examinations and Pap tests did not differ markedly between the study sample and the general population. These results highlight the health impairments of older women who have schizophrenia.

Both men and women who have schizophrenia have higher mortality rates and lower rates of health-promoting behaviors than the rates observed in the general population (1,2). However, the relative risks of suicide and obesity in this patient group are higher among women than men (3,4). The purpose of this study was to assess health behaviors and health status in a sample of older women with schizophrenia. Data from our sample were compared with those from age-matched samples from the general population.

Methods

The study sample was recruited from outpatient rehabilitation programs affiliated with the Sheppard Pratt Health System in central Maryland. Inclusion criteria were female gender, a documented diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and age of 40 to 70 years.

After providing written informed consent, each participant was interviewed with a survey instrument containing items from the Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (BRFS) (5) to provide information about physical health status, routine and preventive health care, addictive behaviors, and comorbid medical conditions. The interviews were conducted from November 1999 to September 2000. The study was approved by Sheppard Pratt's institutional review board. Responses from the sample were compared with those of reference populations of approximately the same age range as the study sample from the 1999 Maryland BRFS.

Results

About 90 percent of eligible women who were approached about the study agreed to participate. A total of 43 women participated in the study. The mean±SD age of the sample was 51.9±7.5 years; 18 women (42 percent) were 40 to 49 years of age, 17 (40 percent) were 50 to 59 years of age, and eight (19 percent) were 60 to 69 years of age. The sample included 35 Caucasians (82 percent) and eight African Americans (18 percent). Twenty-three women (53 percent) had never been married, four (9 percent) were currently married, and 16 (37 percent) were separated or divorced. The mean number of years of education was 12.6±2. The modal monthly income was $500 to $750. Twenty-five women (58 percent) received Medical Assistance, 21 (49 percent) were covered by Medicare, and 11 (26 percent) were covered by commercial insurance; some women had more than one type of insurance coverage. All the participants were receiving psychiatric rehabilitation services and had received prescriptions for antipsychotic medications.

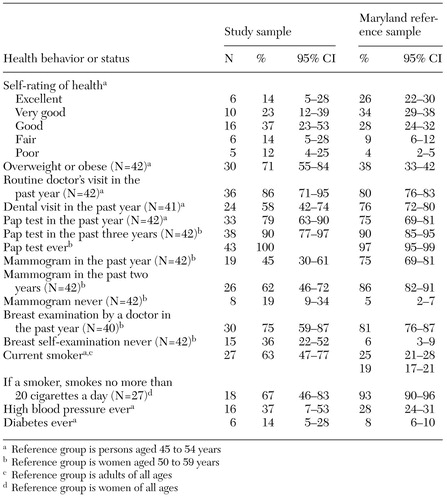

The data for the study sample and for the Maryland reference sample are summarized in Table 1. On several health indicators, the 95 percent confidence intervals for our patients' responses did not overlap with those for the responses of the reference population, which indicates that the responses in our sample are likely to be significantly different from those of the reference group. The body mass index (BMI; in kilograms per square meter) of the women in our sample was significantly higher than that of Maryland women aged 45 to 54 years from the general population. Thirty of 42 women in our sample (71 percent) were classified as overweight or obese, defined as a BMI greater than 27.3, compared with 38 percent in the comparison sample; 13 (31 percent) were obese, defined as a BMI above 30, including four (10 percent) who were morbidly obese (BMI above 40).

The proportion of women in our sample who were current smokers is strikingly high at 63 percent (27 women), compared with 25 percent of Maryland residents aged 45 to 54 years. Our data indicate further that the women in our sample who did smoke were significantly more likely than smokers in the Maryland sample to smoke more than 20 cigarettes a day.

The women in our sample also underused mammography and breast self-examination. Twenty-six women in our sample (62 percent) reported having received a mammogram in the past two years, a rate significantly lower than the 86 percent of women aged 50 to 59 years in the Maryland sample. Also of concern were the eight women (19 percent) who had never had a mammogram; this percentage is significantly higher than the rate of 5 percent in the reference population.

Thirty-six of the women in our sample (86 percent) reported that they had made a routine physician's visit in the past year, which compares favorably with the 80 percent of persons aged 45 to 54 years from the Maryland sample. The proportion of women in our sample who reported having recently received a Pap test was also similar to the proportion of women aged 50 to 59 years in the Maryland sample who had recently received a test. The proportion of women in our sample who had comorbid diabetes or high blood pressure was higher than the proportion in the reference sample, although the difference was not significant.

Discussion and conclusions

The most striking health status characteristics among the women in our sample were their high rates of obesity and smoking and their underuse of mammography.

Our BMI data are consistent with those of Allison and colleagues (3), who found that women with schizophrenia have a significant risk of obesity. Like people in the general population, women with schizophrenia who are obese are more likely to develop other serious medical disorders, including hypertension and diabetes. Obesity also has potential psychological consequences and may compound the poor self-esteem found among women who have schizophrenia.

The high rate of smoking in our sample is consistent with the documented high prevalence of smoking among outpatients with schizophrenia (6). The rate in our sample was also higher than the rate of 22 percent among women nationwide aged 45 to 64 years in 1999 (5).

Underuse of mammography has been noted in the general population among women who are economically disadvantaged and who are in relatively poor health. These factors may be operative among women with schizophrenia (7,8). Studies of the general population have also found relative underuse of mammography among women who do not use regular health care services (9). The latter factor is unlikely to explain the underuse of mammography in our sample, because the rate of routine care in the sample did not differ significantly from that in the comparison group.

The data on comorbid health problems in our sample are consistent with previous reports about the higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes among persons with schizophrenia than in the general population (10).

A limitation of this study was that the data were based on self-reports. Also, our sample was not exactly matched in age to the reference groups, which may have affected the comparisons we made. In addition, our sample consisted of women who were engaged in rehabilitation and outpatient care and thus may not be representative of older women with schizophrenia, many of whom do not receive psychiatric services. Our findings may underreport the health problems and underuse of health care services among older women with schizophrenia.

Dr. Dickerson is director of psychology and Ms. Pater and Ms. Origoni are research technicians at the Sheppard Pratt Health System, 6501 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21204 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue focusing on the health and health care of persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Health behaviors and health status reported by 43 women with schizophrenia and an age-matched general population sample of Maryland residents

1. Brown S: Excess mortality of schizophrenia: a meta analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:502-508, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Holmberg SK, Kane CL: Health and self-care practices of persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 50:827-829, 1999Link, Google Scholar

3. Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Moonseong H, et al: The distribution of body mass index among individuals with and without schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 60:215-220, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Seeman MV, Cohen R: A service for women with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 49:674-677, 1998Link, Google Scholar

5. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 1999Google Scholar

6. Ziedonis DM, Kosten TR, Glazer WM, et al: Nicotine dependence and schizophrenia. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:204-206, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

7. May DS, Kiefe CI, Funkhouser E, et al: Compliance with mammography guidelines: physician recommendation and patient adherence. Preventive Medicine 28:386-394, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Link BG, Northridge ME, Phelan JC, et al: Social epidemiology and the fundamental cause concept: on the structuring of effective cancer screens by socioeconomic status. Milbank Quarterly 76:375-402, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Maxwell CJ, Kozak JF, Desjardins-Denault SD, et al: Factors important in promoting mammography screening among Canadian women. Canadian Journal of Public Health 88:346-350, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Dixon L, Postrado L, Delahanty J, et al: The association of medical comorbidity in schizophrenia with poor physical and mental health. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:496-502, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar