A Program for Teaching Psychiatric Residents to Provide Integrated Psychiatric and Primary Medical Care

Abstract

The Psychiatry Primary Medical Care program of the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center teaches psychiatric residents to provide integrated psychiatric and medical care in a primary care setting. During the program's first year of operation, 34 patients received ongoing integrated care from seven residents. Patients, psychiatric residents, and medical faculty reported a high degree of satisfaction with the program. The duration and frequency of visits reflected the substantial mental health and primary care needs of the population. Patients frequently missed appointments. Barriers to starting and maintaining the program included space constraints and the amount of supervision required.

Editor's note: This paper is the first in a new series of papers by, about, and for residents edited by Avram H. Mack, M.D. Prospective authors—current residents, fellows, and faculty members—should contact Dr. Mack at the Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Unit 74, New York, New York 10032; e-mail, [email protected].

Patients with severe and persistent mental illness often have important unmet medical needs and limited contact with primary providers of medical care (1,2,3). Traditionally, primary medical and mental health care have been separated, creating barriers to care and to the coordination of treatment for patients with severe and persistent mental illness (4,5,6,7). Psychiatric consultation and collaborative treatment programs have been developed for outpatient medical settings (8), but these programs specialize in treating anxiety and depressive disorders and place much of the responsibility for the delivery of mental health care with primary care providers.

A few programs that integrate ambulatory medical and psychiatric care for patients with severe and persistent mental illness have been created (6,7), and other models for integrating care have been proposed (9). However, little has been published about existing integrated programs for this patient population (6,7).

In late 1998 we created the Psychiatry Primary Medical Care (PPMC) program to provide integrated medical and psychiatric ambulatory care at the Portland Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center. Here we describe the program, characteristics of the patients, and satisfaction among patients, residents, and faculty during the first 12 months of the program.

The primary mission of the PPMC program is to teach psychiatric residents to provide integrated primary medical and psychiatric care to patients with serious and persistent mental illness. Although not all patients who are treated by PPMC residents receive integrated care—that is, some receive psychiatric or medical care only—this study focused on patients who received integrated care.

Psychiatric residents enter the PPMC track during their second or third postgraduate year and remain in the program through the remainder of their residency. The PPMC program takes place for half a day a week in ambulatory medical clinics, where PPMC residents work side by side with medical residents. Psychiatry and medical faculty preceptors provide on-site supervision. PPMC residents attend a preclinic conference on topics in primary medical care and participate in an additional weekly conference devoted to topics at the primary care-psychiatry interface.

Patients must have at least one chronic psychiatric disorder to be enrolled in the PPMC program and are recruited from the mental health triage service, the inpatient psychiatry unit, and the ambulatory care and mental health clinics. In general, patients who have severe character pathology are excluded from the program. Patients who participate in the program may have any—and multiple—medical diagnoses but are usually excluded if their medical illness is severe or complex. Care is provided on the basis of a solo-practitioner model, and residents provide limited case management services to their patients. For example, residents often call to remind patients of important appointments, and they communicate and coordinate care with other providers and caregivers. In addition, some patients are enrolled in ancillary mental health programs, such as day treatment and skills classes. For any PPMC clinic visit, the focus of treatment may be medical, psychiatric, or both.

Methods

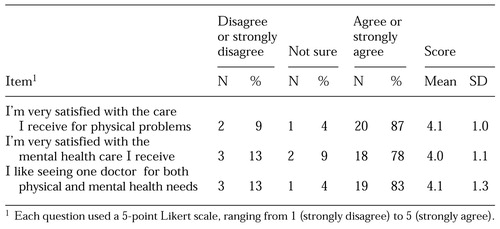

The local institutional review board approved the protocol for the study. Using the VA information system, we reviewed patients' records to determine diagnoses, hospitalizations, attendance at appointments, and referral sources. We obtained current addresses for 31 (91 percent) of the 34 integrated care patients and sent them satisfaction questionnaires through two mailings. PPMC residents and medical faculty were asked to complete satisfaction questionnaires, and their responses were coded and transcribed by a research assistant so that individual respondents could not be readily identified. The surveys used 5-point Likert scales for all items, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Results

During the first 12 months of the program (November 1998 to November 1999), seven residents delivered integrated care to 34 patients during 174 visits. The mean±SD number of visits per patient per year, corrected for duration of enrollment in the program, was 7.7±4.3. Most visits lasted about 45 minutes, and residents usually addressed active medical and psychiatric concerns during the same visit. Of 278 scheduled appointments during the study period, 104 (38 percent) were either canceled or missed. Residents frequently contacted patients by telephone to assess their status and to encourage them to keep their appointments.

Three patients were recruited during psychiatric hospitalizations; most other patients were transferred to the PPMC program from other mental health providers or referred from the mental health triage service. Sixteen (47 percent) of the 34 patients had a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, eight (24 percent) had bipolar disorder, two (6 percent) had panic disorder, and eight (24 percent) had other primary diagnoses, including substance abuse. Five patients (15 percent) required psychiatric hospitalization during the study period.

Thirteen patients (38 percent) had three or more chronic medical conditions, and ten (29 percent) had one chronic medical condition or none at all. Seventeen (50 percent) had hypertension, and five (15 percent) had type II diabetes. We used an adaptation of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scale (10) to rate illness severity. Six patients (18 percent) had ASA scores of 1, indicating minimal or minor physical illness, and 27 patients (80 percent) had ASA scale scores of 2, indicating mild to moderate physical illness. One patient had an ASA scale score of 3, indicating severe systemic disease that limited activity but was not incapacitating; the patient required medical hospitalization and died of sepsis during the hospitalization.

A total of 23 (74 percent) of the 31 patients with current addresses returned questionnaires. No significant differences were observed in demographic or diagnostic characteristics between patients who responded to the questionnaire and those who did not (data not shown). As Table 1 shows, patients generally reported a high degree of satisfaction with the program. However, two patients reported dissatisfaction with most aspects of the program.

All seven residents and all six participating medical faculty completed satisfaction questionnaires. Six residents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement "I'm glad I am participating in this educational experience," and seven agreed or strongly agreed with the statements "I receive adequate medical supervision" and "I receive adequate psychiatric supervision." All six medical faculty reported being satisfied or very satisfied with the supervision they provided and with the quality and abilities of the psychiatric residents. Five of the medical faculty were satisfied or very satisfied with the care provided to PPMC patients overall, and one was unsure.

Discussion

During PPMC's first year of operation, most patients were satisfied with the medical and psychiatric care provided by the PPMC program and liked seeing one provider. Medical faculty found teaching in the program to be gratifying. Residents were satisfied or very satisfied with the level of medical and psychiatric supervision they received. Residents saw their patients frequently and for longer periods than traditional medical appointments.

Many patients who entered the program were new to the region, had not recently received mental health care, or had unmet social needs. Others were referred by mental health and primary care clinicians because they had unmet medical needs, were not stable, or had problems with adherence to treatment regimens. Thus the typical patient in the program had multiple medical problems and problems with adherence and was initially not psychiatrically stable.

Despite the high levels of satisfaction reported by participants, there are several ongoing challenges to the PPMC program. Because the caseloads of PPMC residents are smaller than those of medical residents, space constraints have led to scrutiny of the program. Given the small number of patients being treated, the supervision requirements are high. These challenges are primarily attributable to the teaching mission of the PPMC program. The program could be modified for nonteaching medical or mental health clinical settings and could be made more efficient by having case managers share aspects of care and encourage patients to keep their appointments. PPMC training could be expanded to include nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

Studies are needed to enable us to better understand the effects of this integrated approach on outcomes, service use and cost, and residents' careers. To this end, we are conducting a study of outcomes and resource use among patients who receive PPMC integrated care and a matched group of patients who are treated in separate mental health and primary care clinics.

The authors are affiliated with the behavior health and clinical neurosciences division of the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center and with the department of psychiatry of the Oregon Health and Sciences University in Portland. Send correspondence to Dr. Dobscha at the Portland VA Medical Center, P.O. Box 1034 (P3MHDC), Portland, Oregon 97207 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Satisfaction ratings among 23 patients of a program that provides integrated psychiatric and primary medical care to veterans

1. Maricle RA, Hoffman WF, Bloom JD, et al: The prevalence and significance of medical illness among chronically mentally ill outpatients. Community Mental Health Journal 23:81-90, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Koran LM, Sox HC Jr, Marton KI, et al: Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients: I. results in a state mental health system. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:733-740, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Kamara SG, Peterson PD, Dennis JL: Prevalence of physical illness among psychiatric inpatients who die of natural causes. Psychiatric Services 49:788-793, 1998Link, Google Scholar

4. Bindman J, Johnson S, Wright S, et al: Integration between primary and secondary services in the care of the severely mentally ill: patients' and general practitioners' views. British Journal of Psychiatry 171:169-174, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Shore JH: Psychiatry at a crossroad: our role in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1398-1403, 1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Felker B, Workman E, Stanley-Tilt C, et al: The psychiatric primary care team: a new program to provide medical care to the chronically mentally ill. Medicine and Psychiatry 1:36-41, 1998Google Scholar

7. Cope DW, Sherman S, Robbins AS: Restructuring VA ambulatory care and medical education: the PACE model of primary care. Academic Medicine 71:761-771, 1998Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, et al: Stepped collaborative care for primary care patients with persistent symptoms of depression. Archives of General Psychiatry 56:1109-1115, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Scheffler R, Grogan C, Cuffel B, et al: A specialized mental health plan for persons with severe mental illness under managed competition. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 44:937-942, 1993Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Dripps RD, Eckenhoff JE, Vandam LD (eds): Introduction to Anesthesia: The Principles of Safe Practice, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 1988Google Scholar