Undertreatment Before the Award of a Disability Pension for Mental Illness: The HUNT Study

Mental illnesses, mostly of a nonpsychotic nature, have overtaken musculoskeletal problems as the main reason for disability benefit claims or their equivalent throughout member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) ( 1 ). The impact of mental illness on permanent work-related disability is particularly strong among younger employees ( 2 ), who consequently face many more years of social exclusion. Developing interventions to address the growing societal challenge from mental illness is a major public health issue. In general, mental health problems are considered to be undertreated; in the United States and other developed countries up to half of all persons with mental illness receive no treatment ( 3 ).

A recent initiative in the United Kingdom has focused on improving availability and access to evidence-based psychological therapies for persons with mental health problems. The hope for economic benefits has led to an unusual cofunding arrangement, with support from both the national Department of Health and the Department of Work and Pensions ( 4 ). The underlying assumptions of this initiative are that persons entering the disability benefit system have not had access to appropriate treatment and that the known effectiveness of these treatments in alleviating psychological distress will translate into improved job retention and reintegration into the job market. Although limited, there is evidence to support the latter assumption ( 5 , 6 ). The only available evidence for the first assumption is from a Finnish study of psychiatrists' reports of treatment efforts before awards of disability pensions for DSM-III-R major depression, which showed that in most cases only one series of antidepressant therapy was attempted before the individual left the workforce permanently ( 7 ).

The purpose of this study was to use the unique linkage of a health survey and social security data in Norway, one of many OECD countries with a rising prevalence of mental illness among persons receiving disability benefits, to examine the frequency of undertreatment of mental health problems among those awarded disability pensions for mental illness.

Methods

This historical cohort study used data based on physician-certified diagnoses for disability pension claims obtained from the Norwegian National Insurance Administration. Diagnoses are made according to ICD-9 criteria. They are certified as the primary cause of disability or as a secondary and important factor contributing to disability.

These data were linked through an individual's national identity number to a population-based health screening—the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT-2)—which was carried out from 1995 to 1997. Details of the health survey are available elsewhere ( 2 , 8 ). Briefly, all inhabitants in Nord-Trøndelag County who were over 20 years old were invited to participate in a general health survey, and 71% participated (N=65,648). We identified participants who had been awarded a disability pension for mental illness up to five years before the survey (N=403). We estimated the frequency of undertreatment by examining responses to the survey question "Have you ever sought help for mental problems?"

In post hoc analysis, we examined differences in health status between those who received treatment and those who did not by using another item from the survey—"How is your health at present?" There were four possible answers, from very good, coded 4, to poor, coded 1. Further, we examined differences in help-seeking propensity as a function of the length of time between the disability pension award and participation in the health survey.

HUNT-2 was approved by the National Data Inspectorate and the Board of Research Ethics in Health Region IV of Norway. Written informed consent was obtained from all respondents included in this study.

Results

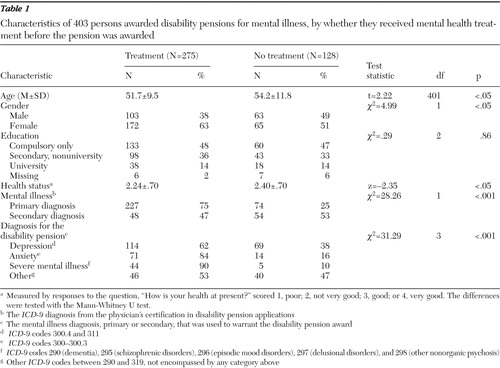

Of 1,918 disability pension awards during the five years before the health survey, 403 (21%) were for a mental illness. A total of 128 of these persons (32%, 95% confidence interval [CI]=27%–36%) reported never having sought help for any mental problems ( Table 1 ).

|

Among the 403 participants, having sought treatment was related to being female (p<.05) and younger (p<.05) but not to educational level. Of the 301 persons who were granted a disability pension who had a mental illness as the primary diagnosis, 25% (CI=19%–29%) reported never having sought help, compared with 53% (CI=43%–63%) of the 102 who had a mental illness as a secondary diagnosis (p<.001).

As Table 1 shows, type of psychiatric diagnosis was associated with having sought treatment before the award (p<.001); those who had depression and a diagnosis in the "other" category were less likely to report treatment seeking than those who had a severe mental illness or anxiety. Those who sought treatment had worse subjective health status than those who did not (p<.05), but no correlation was found between treatment seeking and the length of time between award of the pension and participation in the health survey.

Discussion and conclusions

To receive a disability pension in Norway, a person must have a medically certified permanent incapacity to work despite treatment and rehabilitation efforts. Thus by definition every person awarded a disability pension must have had several consultations with a physician, who presumably would offer treatment. However, one-quarter of people who were recently granted a pension primarily for a mental illness reported that they had never sought help for mental problems. Moreover, in cases in which the certifying physician listed mental illness as the secondary diagnosis, more than half of awardees reported not seeking help. These data suggest a significant level of undertreatment of mental illnesses, particularly depression, before disability pensions are awarded.

Access to health care and the incidence and diagnostic distribution of disability pensions in the county studied were similar to those in the rest of Norway ( 8 ). In Norway and the United States, treating physicians do most of the assessments for disability status, whereas in other OECD countries greater intervention and monitoring by appointed insurance officers is required ( 9 ).

The study has some potential limitations. Information on help seeking for mental illness was self-reported and framed in a lifetime perspective. In some cases, patients may not have reported actual treatment because of stigma, recall bias, or lack of knowledge. This could inflate our estimation of undertreatment. However, given the seriousness of the final outcome—permanent work incapacity—it does not seem likely that an individual could be so uninformed and simply a passive receiver of interventions leading to this outcome. Of note, although the pension awardees in this study may have received medication, only 9% in the Finnish study had received regular psychotherapy of any kind before being awarded a disability pension for major depression ( 7 ). Reports of lack of treatment may reflect lower compliance or poorer engagement with services, leading to a circular pattern of reduced effectiveness of treatment, poorer outcome, and less reported treatment.

We doubt that these limitations explain all of the undertreatment for mental illness identified in this study, and we suggest that treatment for mental problems before the award of disability pensions is underutilized. Although treatment of mental illnesses increased during the past decade, most of the increase was among persons with less severe mental illnesses ( 10 ), who are less likely to be candidates for a disability pension. Recent studies have also shown that anxiety, depression, and insomnia are underestimated as risk factors for disability pensions, even in awards for allegedly pure somatic causes ( 2 , 11 ). Finally, the survey asked about lifetime use of mental health care, and a person's past use of care may have been unrelated to the current award of a disability pension. Consequently, the true figure for undertreatment of mental illnesses may be even higher.

Although level of education has been found to predict award of a disability pension ( 8 ) and help seeking in mental illness ( 12 ), it did not explain any difference in treatment in this study. Our study sample was selected on the basis of health problems that were likely to be proximal predictors of health behavior, which may have rendered more distal factors, such as education, less relevant. Also, because the education level in this sample was lower and less heterogeneous than in the general population, it is less likely that systematic differences in education can explain differences in treatment.

Undertreatment of mental illness—even when the illness has been recognized—could result from an inadequate supply of mental health specialists. As noted above, a recent initiative in the United Kingdom aims to increase the availability of empirically supported psychological treatments, which are hypothesized to prevent some people with mental illness from ending up on disability rolls ( 4 ). However, even in the United States, which has many more accessible treatments, there remains a mismatch between illness and treatment ( 10 ). If efforts are to be justified on a cost savings basis—for example, lower expenditures for disability benefits or reductions in absence from work—interventions must be carefully targeted. Individuals who receive disability benefits report more impairment than working individuals, but this difference is only partly explained by more mental or physical symptoms or diagnosable conditions among the benefit recipients ( 13 ). Although depression and anxiety are synchronous with self-reported disability ( 14 ), mental health interventions that are effective in improving symptoms may not directly translate into improved job retention. If they are effective, the utility of psychological interventions might outweigh that of pharmacological approaches. For instance, in a cognitive-behavioral therapy framework, it would be appropriate to address a patient's perceptions and concerns that might influence work ability, as well as fears related to return to work.

Undertreatment of mental illness despite its recognition might also stem from physicians' negative views of treatment and chronicity and also from patients' unwillingness to accept a diagnosis of mental illness and treatment ( 15 ). In some cases, the administration of treatment may have been less than explicit; for example, a clinician may have called an antipsychotic a "relaxant," leaving the patient unaware and unable to report this as treatment for mental illness. If better access to treatment leads to improved and increased use of treatment, issues related to stigma among both patients and general practitioners must be addressed ( 15 ). Work-related disability may stem from subclinical mental problems; however, they cannot account for the results of this study because all participants had had a recognized syndrome to which the disability was attributable. In addition to issues of stigma and discrimination, patients with mental illnesses might be regarded as unprofitable in the labor market, which can make workforce reentry harder to achieve ( 8 ). Further studies of the relative importance of reasons for undertreatment among individuals awarded disability pensions are needed.

Studies of the general population have identified obstacles to treatment. These obstacles may be even more relevant for patients who face work disability. Mental illness has few objective correlates, and in litigation it may be harder to prove the presence of mental illness. The higher rate of undertreatment found among persons for whom mental illness was a secondary but contributing factor in disability may indicate that patients and physicians focus attention and treatment efforts on the primary condition, which in these cases is often somatic.

Even with these methodological and reporting limitations, the results suggest that through improved accessibility and treatment, there is considerable scope to prevent people with mental illness from leaving the workforce and experiencing deleterious effects on their income and quality of life. If this is the case in a high-income country with universal health coverage such as Norway, the effect may be much stronger in countries where some residents have little or no health care coverage.

On a policy level, increased involvement of mental health specialists in treatment before disability pensions for mental illnesses are awarded should be considered. Beyond individual approaches, changing the process of awarding disability benefits to persons with mental illness also requires a greater understanding of how working life, health care, and social policy interact and mitigate the effects of psychiatric symptoms on employment status ( 8 ).

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT Study) is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre of the Faculty of Medicine at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, the Norwegian Institute of Public Health, and Nord-Trøndelag County Council and receives funding from these organizations.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Prinz C: Disability Programmes in Need of Reform. OECD Policy Brief. Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003Google Scholar

2. Mykletun A, Overland S, Dahl AA, et al: A population-based cohort study of the effect of common mental disorders on disability pension awards. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1412–1418, 2006Google Scholar

3. World Health Organization: Prevalence, Severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA 291:2581–2590, 2004Google Scholar

4. Layard R: The case for psychological treatment centres. BMJ 332:1030–1032, 2006Google Scholar

5. Wang PS, Beck AL, Berglund P, et al: Effects of major depression on moment-in-time work performance. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1885–1891, 2004Google Scholar

6. Wang PS, Patrick A, Avorn J, et al: The costs and benefits of enhanced depression care to employers. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:1345–1353, 2006Google Scholar

7. Isometsa ET, Katila H, Aro T: Disability pension for major depression in Finland. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1869–1872, 2000Google Scholar

8. Krokstad S, Westin S: Disability in society: medical and non-medical determinants for disability pension in a Norwegian total county population study. Social Science and Medicine 58:1837–1848, 2004Google Scholar

9. Transforming Disability Into Ability: Policies to Promote Work and Income Security for Disabled People. Edited by Prinz C. Paris, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2003Google Scholar

10. Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, et al: Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine 352:2515–2523, 2005Google Scholar

11. Sivertsen B, Overland S, Neckelmann D, et al: The long-term effect of insomnia on work disability: the HUNT-2 historical cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology 163:1018–1024, 2006Google Scholar

12. Roness A, Mykletun A, Dahl AA: Help-seeking behaviour in patients with anxiety disorder and depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 111:51–58, 2005Google Scholar

13. Overland S, Glozier N, Maeland J, et al: Employment status and perceived health in the Hordaland Health Study (HUSK). BMC Public Health 6:219, 2006Google Scholar

14. Ormel J, Von Korff M, Van den Brink W, et al: Depression, anxiety, and social disability show synchrony of change in primary care patients. American Journal of Public Health 83:385–390, 1993Google Scholar

15. Mechanic D: Barriers to help-seeking, detection, and adequate treatment for anxiety and mood disorders: implications for health care policy. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:20–26, 2007Google Scholar