Adapting Evidence-Based Practices for Persons With Mental Illness Involved With the Criminal Justice System

The overrepresentation of persons with mental illnesses in the criminal justice system is well documented ( 1 , 2 ). Prevalence estimates of serious mental illness in jails range from 7% to 16%, and compared with the rates in the general population, men with mental illness are four times more likely to be incarcerated and women with mental illness are eight times more likely to be incarcerated ( 3 ). Some of the key factors contributing to this phenomenon are high rates of co-occurring substance use disorders among persons with mental illnesses ( 4 , 5 , 6 ) coupled with national drug policy emphasizing interdiction with stiff criminal penalties; harsh jail and prison environments that are difficult for persons with serious mental illnesses to navigate ( 7 ); inadequate community resources increasing delays in release from jail and prison to community; inadequate reentry planning, leaving returning inmates ill prepared for community reintegration; and inadequate access to evidence-based practices when utilizing alternatives to incarceration ( 8 ). This last point is seen as especially critical for the wide array of jail diversion and reentry programs being created throughout the United States.

In a review of the recent jail diversion efforts, Steadman and Naples ( 8 ) observed that although the mechanics for identifying and administratively diverting persons with serious mental illness can be implemented, there has been little evidence that access to community services reduces rates of rearrest. They interpreted this finding as indicating lack of access to evidence-based practices appropriate for the clinical conditions of the divertees. This finding was particularly true for integrated co-occurring disorder treatment and assertive community treatment (ACT) teams. Other authors have pointed out that often diversion and reentry programs do not target risk factors associated with recidivism ( 9 ) and that evidence-based practices that have been established by their effect on primary behavioral health outcomes have little effect on public safety outcomes.

As more communities attempt to offer appropriate and effective services in diversion and reentry programs, a major issue that has become apparent is that adaptations to the standard evidence-based practices often are required because of the legal predicaments faced by clients involved with the criminal justice system. The evolution of forensic ACT teams is but one example of this ( 10 ). The associated question is how extensive can adaptations be before fidelity to the proven practice is so compromised as to no longer have the requisite empirical basis for expecting positive outcomes? To better understand these pressing issues, the National GAINS Center for Evidence-Based Programs in the Justice System held a series of six meetings focused on evidence-based practices and their applicability to persons involved in the criminal justice system. This Open Forum integrates the results of those meetings and proposes future steps to establish relevant evidence-based practices that can have an effect on both behavioral health and public safety outcomes for persons involved in the criminal justice system.

Factors affecting the delivery of evidence-based practices

In selecting the topics for the six expert panels, organizers were directed by the common, and at times unique, clinical and social needs of this heterogeneous population. The following phenomena associated with persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system must be planned for in the design of effective service interventions.

Co-occurring substance use disorders

The prevalence of high rates of co-occurring mental and substance-related disorders within the general population has been well documented ( 5 , 6 ). Even the highest estimates of co-occurring disorders by condition in the general population are low compared with best data about the prevalence of co-occurring disorders in jails and prisons. Abram and Teplin ( 11 ) found that about 8% of the jail inmates have a current serious mental illness and that 72% of both male and female jail detainees with serious mental illness had a co-occurring substance use disorder. In one study, almost one-quarter of veterans with co-occurring disorders released from inpatient facilities were incarcerated within 12 months of discharge ( 12 ), and rates of incarceration are generally higher for persons with co-occurring disorders, compared with those with mental illness alone ( 13 ).

Sociodemographic factors

In 2000 nonwhites constituted 25% of the general U.S. population but 62% of the prison population and 57% of the jail population ( 14 ). In a study of nonwhite persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system, inadequate attention to cultural issues was reported at every point of contact with the justice system ( 15 ).

Finding and keeping a job after incarceration is critical to address basic needs and to structure daily life for persons with mental illnesses. Research has shown that persons with serious mental illness want to work and can work, but as a group they are typically unemployed. Only 10%–20% of persons with serious mental illness are currently working ( 16 ). Persons released from incarceration compete with other low-income and low-education workers for low-wage jobs, yet they face policies and discriminatory hiring practices that make it more difficult to succeed. Some research supports vocational training and employment as antidotes to reincarceration ( 17 ), but little specific research has addressed this dimension among persons with serious mental illness.

Persons with mental illness who are homeless are at high risk of incarceration, and when incarcerated, they stay in custody for longer periods ( 18 ). They are more likely to come in contact with law enforcement officers and be charged with a crime ( 19 ). In jails 30.3% of inmates with mental illnesses were homeless in the year before arrest, compared with 17.3% of other inmates ( 20 ). Not having a home upon release from jail or prison also increases the risk of rearrest.

Trauma exposure

Critical to contemplating effective interventions for persons involved in the criminal justice system is an awareness of the potential for them to have an extensive history of trauma before incarceration. Women are a fast-growing segment of arrestees and currently account for 12.3% of the U.S. jail population ( 21 ). A majority of these women are persons of color, in their 20s and 30s, and unmarried; seven of ten of these women have dependent children in the community; and a majority of these women have a history of irregular education and employment ( 22 ). They have experienced high rates of childhood and adult physical and sexual abuse ( 3 , 22 , 23 ). In 2002 a history of physical or sexual abuse was reported by 55% of women in jail ( 23 ), and 27% reported rape ( 24 ). Women with a history of abuse have an increased risk of alcohol and substance abuse ( 22 ).

Criminal charges

Two aspects that clearly distinguish persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system from those without such a history are high rates of criminal behavior and experiences within jail and prison settings. Although persons with mental illness are not necessarily more violent than those without such an illness ( 25 ) and although many arrests of persons with mental illnesses are for misdemeanors associated with "crimes of survival" (that is, panhandling or urinating in public), the association between comorbid antisocial personality disorders and high rates of conviction for criminal offenses creates a cohort of individuals with unique needs. "Criminogenic thinking" is the criminal justice term used to convey cognitive differences between criminals and law-abiding citizens; having a mental illness does not immunize one from these patterns of thought. Second, people who spend extended periods of time in custody are exposed to a different culture and experience stressful periods that include threats to their well-being and periods of isolation. In response to these circumstances, persons with mental illnesses may develop adaptive behaviors that interfere with subsequent community adjustment ( 26 ).

Legal factors: the unique role of coercion

Coercion is a consideration in the application of all evidence-based practices to persons involved in the criminal justice system. First, measurable public safety outcomes include abstinence from all substances of abuse, adherence to prescribed medications, and participation in mental health and substance abuse treatment groups. These objective conditions are often written into terms and conditions of release, and the failure to achieve these standards can be used as a justification for reincarceration. Second, for an individual who has not been in treatment, incarceration represents an opportunity to engage that person, mandate treatment interventions that can reduce high-risk behavior, optimize other treatment strategies (for example, medication management) in a controlled setting, and closely monitor the person's behavior. The effectiveness of coercive strategies for persons with co-occurring disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system is essentially unknown ( 27 ).

From the perspective of the person involved in the criminal justice system, the perception of coercion may be more important than the extent to which the coercion is applied ( 28 ). The Institute of Medicine suggests that when coercion is legally authorized, patient-centered care is still applicable and client decision making should be maximized by involvement in the selection of treatments and providers ( 29 ).

If desired public health and public safety outcomes are to be achieved, these clinical, social, and legal features of persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system must be addressed. What evidence exists to show that current practices can achieve these objectives? Are the evidence-based practices that have been developed to generate positive behavioral health outcomes also associated with reductions in criminal activity, rearrest, and reincarceration?

Expert panel meetings

In 2005 the National GAINS Center convened six expert panel meetings to review ACT, housing, trauma interventions, supported employment, illness self-management and recovery, and integrated treatment. Discussion papers and overview documents were created for each panel by experts in each topical area mentioned above and circulated among attendees before the meeting (see box on this page for a list of the papers and their authors). Panel participants consisted of researchers, program directors and clinicians, and consumers in the field. They discussed the current knowledge of the intervention's effectiveness in three dimensions: the completeness and accuracy of the research review on the evidence-based practice, the completeness and accuracy of the literature on any adaptations specifically for persons in involved in the justice system, and the application of the research base to current programming.

Discussion papers for the expert panels a

Supported Employment for People in Contact With the Criminal Justice System, by William A. Anthony

Extending ACT to Criminal Justice Settings: Applications, Evidence, and Options, by Joseph Morrissey and Piper Meyer

Principles and Practice in Housing for Persons With Mental Illness Who Have Had Contact With the Justice System, by Caterina Gouvis Roman, Elizabeth Cincotta McBride, and Jenny W. L. Osborne

Illness Management and Recovery for People in Contact With the Criminal Justice System, by Kim T. Mueser

Integrated Mental Health/Substance Abuse Responses to Justice Involved Persons With Co-occurring Disorders, by Fred C. Osher

Evidence-Based Trauma Services for Persons in the Criminal Justice System, by Bonita M. Veysey

Making the Case for a Trauma Informed Criminal Justice System, by Susan Davidson

a All papers and summary fact sheets are available at the GAINS Center's Web site: www.gainscenter.samhsa.gov.

Expert panel findings

Integrated mental health and substance abuse services

The documented high prevalence rates of co-occurring mental and substance use disorders among persons involved in the criminal justice system demands an inspection of effective interventions to reduce these illicit and destabilizing behaviors. For persons with co-occurring disorders who are not involved in the criminal justice system, integrated treatment has been identified as an evidence-based practice, and its core components have been articulated ( 30 , 31 , 32 ).

For persons involved in the criminal justice system, the hypothesis underpinning effective interventions for co-occurring disorders can be stated as the following: interventions (at the program or provider level) that reduce substance use (licit and illicit) and improve levels of functioning among persons with co-occurring disorders will reduce both the frequency of involvement with the justice system and the time spent in justice settings or under correctional supervision. The outcomes sought are reduced criminal activity (specifically the use of illegal drugs and violent behavior), fewer persons with co-occurring disorders at all points in the justice system, and improved reintegration of offenders with co-occurring disorders into community settings. Specific treatments within integrated programs include psychopharmacologic strategies ( 33 ), motivational interventions ( 34 ), and cognitive-behavioral interventions ( 32 ). Several specific program models that use integrated treatments have been applied to persons with co-occurring disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system.

First, the integrated dual disorder treatment model is an evidence-based practice that combines program components and treatment elements to ensure that persons with co-occurring disorders receive combined treatment for substance abuse and mental illness from the same team of providers ( 35 ). Although routinely applied to persons with serious mental illness involved in the criminal justice system, the model has not been specifically studied for its impact on criminal justice outcomes.

Second, the modified therapeutic community is a residential treatment program for persons with co-occurring disorders that uses integrated strategies that have been studied in populations involved in the criminal justice system ( 36 ). Modified therapeutic communities use the "community as method" as the basis for both the program and treatment integration. Compared with nonintegrated services, modified therapeutic communities have been shown to significantly lower reincarceration rates and reduce harmful substance use among persons with co-occurring disorders ( 37 ).

Finally, ACT is reviewed below, but it should be noted that when the model is implemented with high fidelity, it achieves positive outcomes for persons with co-occurring disorders, although its impact on public safety outcomes remains to be established.

Although some services integration models have data to support their effectiveness as evidence-based practices for persons with co-occurring disorders who are involved in the criminal justice system, more specific tests are needed of integrated treatment for cohorts involved in the criminal justice system.

Supportive housing

The housing situations for persons with mental illness who have contact with the criminal justice system range from owning their own homes or living in independent rental units to institutional care. It is also the case that housing type for any individual will vary over time. There has been a concerted focus on the utility of supportive housing for individuals with a history of mental illness and housing instability. Supportive housing includes a variety of permanent housing settings coupled with on-site or easily accessible services. Services include case management, counseling, medical care, mental health and substance abuse treatment, vocational training, cognitive skills groups, and assistance in obtaining income supports and entitlements. These models have proven effective in achieving positive residential outcomes ( 38 ).

No single model or package of services has emerged specifically to persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system. Furthermore, evaluation of the effectiveness of different approaches has not employed rigorous methodology, and measured outcomes vary widely. Culhane and colleagues ( 39 ) found that individuals with mental illness at risk of homelessness who were placed in supportive housing options in New York City had reductions in shelter use and hospitalizations and spent fewer days in jail in the year after attaining housing, compared with the year before attaining housing. In addition, compared with a matched group of New York residents without supportive housing, they had fewer episodes of incarceration. The modified therapeutic community model mentioned above is another example of a supportive housing model producing positive behavioral health and criminal justice outcomes.

Trauma-specific interventions

At the outset of the meeting, it was acknowledged that trauma interventions were not at the level of an evidence-based practice, although they are a promising practice for which there is the beginning of a persuasive database. The topic was included in the evidence-based practice series because of the exceedingly high relevance of this issue for persons with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system.

The high rates of trauma exposure among persons, particularly women, with mental illness who are involved in the criminal justice system require a systemic response that views trauma history as the norm rather than an exception. As an evidence-based practice for persons involved in the criminal justice system, a trauma-specific intervention assumes that effectively dealing with symptoms of trauma will reduce the likelihood of subsequent criminal activity. Although a number of effective trauma interventions for the general population with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been described, applications for persons involved in the criminal justice system are not common. Zlotnik and colleagues ( 40 ) applied a well-established cognitive-behavioral model for the treatment of PTSD ( 41 ) to a cohort of incarcerated women with PTSD and substance dependence and found positive outcomes consistent with its application among nonincarcerated women. Valentine and Smith ( 42 ) used traumatic incident reduction in a sample of female prisoners and found significant reductions in trauma-related symptoms. However, although these and other small-scale studies suggest that trauma-specific interventions for persons involved in the criminal justice system can positively affect trauma symptoms, no evidence exists that these interventions reduce rates of rearrest and jail utilization.

Supported employment

If some criminal activity is driven by the need for money, successful employment may mitigate subsequent contact with the criminal justice system. Over the past 15 years supported employment has emerged as an evidence-based practice that can improve the success of persons with serious mental illness in competitive employment circumstances ( 43 , 44 ). In a multisite, randomized clinical trial, Cook and colleagues ( 45 ) showed that participants in a supported employment program were twice as likely as persons who were enrolled in traditional vocational programming to achieve competitive employment. Although there are limited data that suggest supported employment is effective among persons with mental illness, regardless of whether or not they are involved in the criminal justice system ( 46 ), there are no data on the impact of supported employment on criminal justice outcomes.

There is face validity to the concept that improving employment outcomes for persons involved in the criminal justice system can reduce criminal justice contact. Programs may need to be modified to accommodate conditions of release, which can require court or community correction monitoring concurrent with work hours.

Illness management and recovery

Illness management and recovery are evidence-based practices that teach persons with serious mental illness the required skills to manage their own illnesses in collaboration with health care professionals and other natural supports. The application of these evidence-based practices has been demonstrated to prevent relapse and rehospitalization in addition to reducing the disabling effects of mental health symptoms ( 47 ). There are several illness management and recovery program types—for example, the wellness recovery and action plan and the social and independent living skills program—that share practice principles while employing different approaches. These programs have been implemented for persons with mental illness within correctional settings and appear to produce the expected gains in social skills. There is no evidence concerning the effect of illness management and recovery on public safety outcomes.

The common application of psychoeducational and cognitive components within illness management and recovery programs makes them well suited for adaptations that could address unique aspects of persons involved in the criminal justice system. Addressing criminogenic thinking or antisocial tendencies within an illness management and recovery framework could specifically target behaviors that lead to criminal justice contact. Alternatively, using motivational enhancements for consumers in illness management and recovery programs could reduce perceived coercion and may offset any potential negative impact of mandated treatment.

Assertive community treatment

ACT is a well-documented evidence-based practice that combines treatment, rehabilitation, and support services within a multidisciplinary team ( 43 , 44 , 48 ). It is a high-intensity, high-cost service that is typically reserved for persons most disabled by mental illness and those who use multiple community acute and emergency services. The ability of ACT to consistently reduce arrests and jail times among persons with serious mental illness has not been established ( 49 ). As a result, there has been recent interest in augmenting ACT services by specifically focusing on populations involved with the criminal justice system and training team members to be responsive to criminal justice partners ( 10 ). These forensic ACT teams, or FACT teams, have been implemented in many communities around the country. Some demonstration studies have found significant reduction in jail days and arrests ( 50 , 51 ), but these studies had no control groups and used FACT teams that made many adaptations to the original model. Adaptations to intensive case management models have also been applied to populations involved with the criminal justice system, although outcomes have been mixed ( 49 ).

The bottom line for persons with mental illness who are involved in the criminal justice system is that FACT teams are relatively new adaptations of the ACT model and come in many forms. When adhering to the core ACT model, they show promise for reducing inpatient hospitalizations. With their "criminal justice savvy" ( 49 ), they can be expected to reduce recidivism and maintain certain clients in the community. Nonetheless, they are a high-intensity, high-cost intervention that fits the most disabled segment, perhaps 20%, of the persons being diverted or released from the criminal justice system. The case management models of choice for the other 80% or so of less disabled individuals rely on brokering services from mainstream providers rather than providing all services via a FACT team. Although less costly to operate, brokered case management models are still a challenge for many communities with limited services.

Need for adaptation

This review of six evidence-based practices for their impact on persons involved in the criminal justice system suggests that expected clinical outcomes can be obtained but that achieving desired public safety outcomes is not always a result. It is not surprising that treatment interventions do not seem to have a weaker treatment effect on persons involved in the criminal justice system. Often the reasons for arrest and incarceration are related to the social and clinical circumstances that are a part of having a serious mental illness. Persons with mental illness who are involved with the criminal justice system are more similar to than distinct from persons with mental illness who are not involved with such a system.

The most direct causal relationship between criminal justice involvement and the evidence-based practices reviewed is in the area of co-occurring disorders. Because a majority of persons involved in the criminal justice system meet criteria for co-occurring substance use disorders and because integrated treatments are effective in reducing substance use (this often entails the cessation of an illicit activity—that is, drug use), treatment for substance use disorders should result in reduced criminal contact among persons with mental illness. Although there is not an abundance of data that support this assumption, some interventions have been demonstrated to achieve these goals. Perhaps of larger relevance is the lack of access that persons with co-occurring disorders have to integrated care. This is reflected in the finding of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health that almost one-half of persons with co-occurring disorders received no behavioral health services and that among those who were treated, a majority did not receive integrated care ( 52 ).

Supportive housing also stands out as a potential solution to reducing mental disability while improving criminal justice outcomes. The high public visibility of homeless persons coupled with the pressure to commit "crimes of survival" (for example, panhandling and urinating in public) is a recipe for arrest. The relative contribution to positive outcomes of housing itself versus the model of support has not been determined. And many of the solutions to the vexing problem of affordable housing are outside the purview of treatment providers and justice personnel.

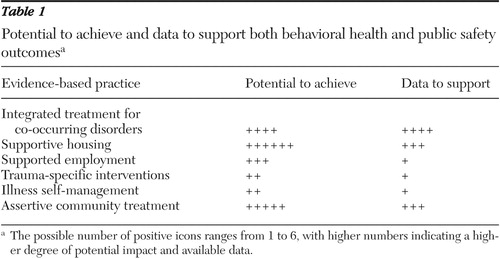

Other evidence-based practices have more of an indirect effect on criminal behavior, but at best their ability to achieve this goal has only limited support in the existing literature to achieve these goals. Table 1 is a summary of available data and the potential effectiveness of existing evidence-based practices as applied with persons involved in the criminal justice system. The greater the number of positive icons, the higher the degree of potential impact and available data. The most striking feature of this analysis is the lack of data to support these practices.

|

Understanding the unique clinical needs of the population involved with the criminal justice system informs the range of services required, but it also suggests that adaptations to the evidence-based practices may be required to achieve program objectives that inevitably have public safety goals as primary outcomes. This is clearly the case in the evolution of FACT teams. Added to the core dimensions of ACT, FACT teams develop expertise in communicating with justice personnel, integrate cognitive strategies targeting the thought processes of the target population, and explicitly cite that a main program goal is to prevent arrest and incarceration. This latter adaptation is likely to be critical to any effort that aims to have a positive impact on public safety. Trauma interventions will need to address the trauma of arrest and incarceration. Likewise, illness self-management for this population should include behavioral lessons that reflect the experience of persons at risk of subsequent criminal justice contact. The unanticipated effect of adaptation can be a reduction in the fidelity of the practice to the previously described evidence-based practice. The impact of variations must be assessed.

Clearly more research is needed to determine the impact of current and emerging evidence-based mental health practices on persons involved in the criminal justice system. Public safety outcomes that address the goals of mental health and criminal justice collaboration, such as rearrest, probation and parole revocation, and days of incarceration, must be evaluated in future studies. In order to achieve positive outcomes in these areas, adaptations to evidence-based practices must reflect the unique circumstances and clinical features of persons involved in the criminal justice system.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported in part by contract 280-03-2004 from Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to the National GAINS Center for Evidence-Based Programs in the Justice System.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Ditton P: Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers. Pub no NCJ 174463. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999Google Scholar

2. The Prevalence of Co-occurring Mental and Substance Use Disorders in Jails. Delmar, New York, National GAINS Center, 2004Google Scholar

3. Teplin LA, Abram KM, McClelland GM: Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among incarcerated women: pretrial jail detainees. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:505–512, 1996Google Scholar

4. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:891–896, 2004Google Scholar

5. Kessler RC: The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry 56:730–737, 2004Google Scholar

6. Results From the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2004Google Scholar

7. Toch H, Adams K: Acting Out: Maladaptive Behavior in Confinement. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 2002Google Scholar

8. Steadman HJ, Naples M: Assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 23:163–170, 2005Google Scholar

9. Skeem JL, Louden JE: Toward evidence-based practice for probationers and parolees mandated to mental health treatment. Psychiatric Services 57:333–342, 2006Google Scholar

10. Weisman RL, Lamberti JS, Price N: Integrating criminal justice, community healthcare, and support services for adults with severe mental disorders. Psychiatric Quarterly 75:71–85, 2004Google Scholar

11. Abram K, Teplin L: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees: implications for public policy. American Psychologist 46:1036–1045, 1991Google Scholar

12. Rosenheck RA, Banks S, Pandiane J, et al: Does closing inpatient beds increase incarceration among users of VA public mental health services? Psychiatric Services 51:1282–1287, 2000Google Scholar

13. Mueser KT, Essock SM, Drake RE, et al: Rural and urban differences in dually diagnosed patients: implications for service needs. Schizophrenia Research 48:93–107, 2001Google Scholar

14. Beck AJ, Karberg JC, Harrison PH: Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2001. Pub no NCJ-191702. Washington, DC, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2002Google Scholar

15. Primm AB, Osher FC, Gomez MB: Race and ethnicity, mental health services and cultural competence in the criminal justice system: are we ready to change? Community Mental Health Journal 41:557–569, 2005Google Scholar

16. Anthony WA, Cohen MR, Farkas MD, et al: Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 2nd ed. Boston, Boston University, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 2002Google Scholar

17. Wilson DB, Gallagher CA, McKenzie DL: A meta-analysis of corrections-based education, vocation and work programs for adult offenders. Journal of Research on Crime and Delinquency 37:347–368, 2000Google Scholar

18. McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC: Incarceration associated with homelessness, mental disorder, and co-occurring substance use disorder. Psychiatric Services 56:840–846, 2005Google Scholar

19. Brekke JS, Prindle C, Bae SW, et al: Risks for individuals with schizophrenia who are living in the community. Psychiatric Services 52:1358–1366, 2001Google Scholar

20. Stephen JJ: Census of Jails, 1999. Pub no NCJ 18663. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2001Google Scholar

21. Harrison PM, Beck AJ: Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin: Prison and Jail Inmates at Midyear 2004. Pub no NCJ 208801. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 2005Google Scholar

22. Greenfeld LA, Snell TL: Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report: Women Offenders. Pub no NCJ175688. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, 1999Google Scholar

23. Clark C: Addressing histories of trauma and victimization in treatment, in Justice-Involved Women With Co-occurring Disorders and Their Children. Edited by Davidson S, Hills H. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center, 2002Google Scholar

24. National Correctional Population Reaches New High: Grows by 117,400 During 2000 to Total 6.5 Million Adults. Washington, DC, US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2001Google Scholar

25. Steadman HJ, Mulvey EP, Monahan J, et al: Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:393–401, 1998Google Scholar

26. Rotter MD, McQuisition HL, Broner N, et al: The impact of the "incarceration culture" on reentry for adults with mental illness: a training and group treatment model. Psychiatric Services 56:265–267, 2005Google Scholar

27. Skeem J, Encandela J, Eno-Louden J: Experiences of mandated mental health treatment in traditional and specialty probation programs. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 21:429–458, 2003Google Scholar

28. Monahan J, Hoge SK, Lidz C, et al: Coercion and commitment: understanding involuntary mental hospital admission. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 18:249–263, 1995Google Scholar

29. Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press, 2006Google Scholar

30. Substance Abuse Treatment for Adults in the Criminal Justice System: Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No 42. DHHS pub no SMA 05-4056. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2005Google Scholar

31. Drake RE, Essock S, Shaner A, et al: Implementing dual diagnosis services for clients with severe mental illness, Psychiatric Services 4:469–476, 2001Google Scholar

32. Mueser KT, Noordsy DL, Drake RE, et al: Integrated Treatment for Dual Disorders: A Guide to Effective Practice. New York, Guilford, 2003Google Scholar

33. Noordsy DL, Green AI: Pharmacotherapy for schizophrenia and co-occurring substance use disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports 5:340–346, 2003Google Scholar

34. Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, et al: The feasibility of enhancing psychiatric outpatients' readiness to change their substance use. Psychiatric Services 53:602–608, 2002Google Scholar

35. Co-occurring Disorders: Integrated Dual Disorders Treatment: Implementation Resource Kit. Rockville Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 2003Google Scholar

36. DeLeon G: Modified therapeutic communities for dual disorders, in Dual Diagnosis: Evaluation, Treatment, Training, and Program Development. Edited by Solomon J, Zimberg S, Shollar E. New York, Plenum, 1993Google Scholar

37. Sacks S, Sacks J, McKendrick K, et al: Modified therapeutic community for MICA offenders: crime outcomes. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 22:477–501, 2004Google Scholar

38. Shern DL, Tsemberis S, Winarski J, et al: The effectiveness of psychiatric rehabilitation for persons who are street dwelling with serious disability related to mental illness, in Mentally Ill and Homeless: Special Programs for Special Needs. Edited by Breakey WR, Thompson JT. Amsterdam, Harwood Academic, 1997Google Scholar

39. Culhane D, Metreaux S, Hadley T: Public service reductions associated with placement of homeless persons with severe mental illness in supportive housing. Housing Policy Debate 13:107–163, 2002Google Scholar

40. Zlotnik C, Najavits LM, Rohsenow DJ, et al: A cognitive behavioral treatment for incarcerated women with substance abuse disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from a pilot study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 25:99–105, 2003Google Scholar

41. Najavits LM: Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. New York, Guilford, 2002Google Scholar

42. Valentine PV, Smith TE: Evaluating traumatic incident reduction therapy with female inmates: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Research on Social Work Practice 11:40–52, 2001Google Scholar

43. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, et al: Assertive community treatment: critical ingredients and impact on patients. Disease Management and Health Outcomes 9:141–159, 2001Google Scholar

44. Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, et al: Implementing supported employment as an evidence-based practice. Psychiatric Services 52:313–322, 2001Google Scholar

45. Cook JA, Lehman AF, Drake R, et al: Integration of psychiatric and vocational services: a multisite randomized, controlled trial of supported employment. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1948–1956, 2005Google Scholar

46. Anthony WA: Supported Employment. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center for Evidence-Based Programs in the Justice System, 2005Google Scholar

47. Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton D, et al: Illness management and recovery for severe mental illness: a review of the research. Psychiatric Services 53:1272–1284, 2002Google Scholar

48. Dixon L: Assertive community treatment: twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services 51:759–765, 2000Google Scholar

49. Morrisey J, Meyer P: Extending Assertive Community Treatment to Criminal Justice Settings. Delmar, NY, National GAINS Center for Evidence-Based Programs in the Justice System, 2006Google Scholar

50. Lamberti JS, Weisman R, Fade DI: Forensic assertive community treatment: preventing incarceration of adults with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 55:1285–1293, 2004Google Scholar

51. McCoy ML, Roberts DL, Hanrahan P, et al: Jail linkage assertive community treatment services for individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 27:243–250, 2004Google Scholar

52. Wright D, Sathe N, Spagnola K: State Estimates of Substance Use From the 2004–2005 National Surveys on Drug Use and Health. DHHS pub no SMA 07-4235, NSDUH series H-31. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2007Google Scholar