Crime Victims and Criminal Offenders Among Adults With Serious Mental Illness

Involvement of adults with serious mental illness in the criminal justice system has been an important research concern for a number of years. This research began with studies of criminal justice involvement of former mental patients ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ) and community mental health service recipients ( 5 ) and of the prevalence of mental illness in incarcerated populations ( 4 ). More recently, this research has expanded to include criminal victimization of adults with serious mental illness ( 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). The later studies have relied primarily on self-reported victimization.

This brief report adds to this research by examining both criminal offending and victimization for the same group of individuals within the same year. Both offending and victimization were measured from the same perspective—that of the investigating officer as represented in official records of contacts with police. The perspective of the investigating officer is particularly important because of its consequences for the person who is categorized as an offender or a victim. Use of official records has the added advantage of providing general population measures with which to compare measures for the individuals with serious mental illness ( 10 ).

Methods

Participants in the study were the 2,610 adults aged 18 years and older who were served by community mental health center (CMHC) programs for adults with serious mental illness in 13 rural Vermont counties from July 2005 through June 2006. Vermont's single urban county was excluded from this analysis because a substantial number of its police departments did not participate in the statewide criminal justice database used in this analysis. Men and women were served in about equal numbers. The largest number of clients were aged 50 years and older (43%), followed by the 35- to 49-year age group (38%) and the 18- to 34-year group (19%). Like the population of the state as a whole, the CMHC caseload is predominantly white (94%).

This study relied exclusively on anonymous extracts from databases maintained by the Vermont Department of Mental Health and Department of Public Safety. The anonymous extract from the community mental health database, which conforms to specifications of the federal Center for Mental Health Services ( 11 ), includes the date of birth, gender, and county of residence for all individuals served by community programs for adults with serious mental illness during fiscal year 2006. The public safety data set, which includes all contacts with participating police organizations, is consistent with U.S. Department of Justice specifications for incident-based reporting systems ( 12 ). The anonymous extract from the Vermont incident-based reporting system includes the date of birth and gender of each individual, the county of the incident, and the investigating officer's characterization of each individual's involvement as an offender or a victim. These data provide a comprehensive compilation of crimes and criminal victimization known to police. These data do not include criminal offending or criminal victimization that does not come to the attention of police.

Because the mental health and public safety data sets do not share unique person identifiers, probabilistic population estimation ( 13 ) was used to determine the unduplicated number of people represented in each data set and the number of individuals represented in both the mental health and the public safety data sets. This statistical procedure provides valid and reliable measures of the size and overlap of data sets that do not include person identifiers. This approach is particularly useful where concerns about the confidentiality of medical records limit the use of person-identifying information ( 14 ).

To compare rates of offending and victimization for mental health service recipients to rates for the general population in Vermont, a relative risk was calculated by dividing the rate for mental health service recipients by the rate for the Vermont general population. A relative risk that is not significantly different from 1 indicates that the rate for service recipients and the rate for the general population are not different.

The institutional review board of the Vermont Agency of Human Services found that this research qualified for exemption from review and therefore from informed consent.

Results

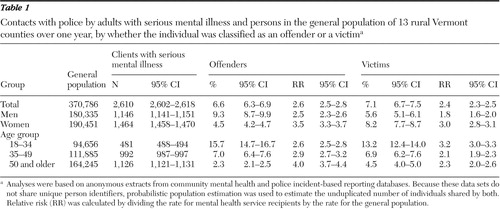

As Table 1 shows, 6.6% of the 2,610 adult CMHC service recipients with serious mental illness in rural Vermont were identified by police as criminal offenders during fiscal year 2006. Men were substantially more likely than women to be identified as offenders (9.3% compared with 4.5%). Identification of offending behavior decreased with increasing age—from 15.7% among those aged 18 to 34 to 2.3% among those aged 50 and older

|

Overall, service recipients were 2.6 times as likely as persons in the general population to be identified as offenders. The elevated risk of being identified as an offender was greater for women than for men and increased with increasing age.

As Table 1 also shows, 7.1% of the service recipients were identified by police as crime victims during fiscal year 2006. Men were less likely than women to be identified as victims (5.6% compared with 8.2%). Identification of victimization decreased with increasing age (from 13.2% among those aged 18 to 34 to 4.5% among those aged 50 and older). Overall, service recipients were 2.4 times as likely as persons in the general population to be identified as victims. The elevated risk of being identified as a victim was greater for women than for men and was greatest in the 18- to 34-year age group.

It is important to note that individuals identified as offenders in one police contact can be identified as victims in another police contact. These categories are not mutually exclusive among service recipients or in the general population. Almost a fourth (24%) of the mental health service recipients who were identified as offenders were also identified as victims in one or more contacts. Almost one in eight (12%) persons in the general population who were identified as offenders were also identified as victims. As has been noted elsewhere, characterization as a victim or an offender is better viewed as an attribute of a specific social situation than as an attribute of a person ( 15 ).

Discussion

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research that shows that adults with serious mental illness are more likely than persons in the general population to be identified as criminal offenders and as crime victims. The relationship between victimization or offending and mental illness, however, is more complex than previously described. Adults receiving community mental health services were significantly more likely to be identified by police as crime victims than as offenders (7.1% compared with 6.6%). Persons in the general population are also more likely to be identified as victims than as offenders (2.9% compared with 2.5%). Thus the higher rate of identification as victims does not make adults with serious mental illness different from the general population.

What distinguishes adults with serious mental illness is that, compared with the general population, their relative risk of being identified as an offender (2.6) was greater than their relative risk of being identified as a victim (2.4). This small but statistically significant difference suggests that the impact of mental illness on criminal offending is somewhat greater than the impact of mental illness on criminal victimization, as measured here. We believe this observation has important implications for understanding the relationship between mental illness and involvement in the criminal justice system. Public policy that is based on an exaggerated impression of the relative risk of either criminal offending by or victimization of adults with serious mental illness would not address the reality described by police in their incident-based reporting system.

The findings reported here are limited to adult CMHC service recipients with serious mental illness in a rural, predominantly white population. Future research should apply an integrated victim-offender model with general population comparisons to urban populations and to more racially and ethnically diverse populations.

Conclusions

Data sets similar to those used in this research are becoming more widely available. These data sets, in combination with emerging methods for measuring caseload overlap without reference to unique person identifiers, provide researchers with the opportunity to mine the rich data stores of mental health and criminal justice databases while protecting the confidentiality of medical records and the personal privacy of individuals. Continued research in this area has the potential to increase our understanding of the relationship between mental illness and criminal victimization and offending as well as other social problems associated with serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This project was supported in part by a State Mental Health Data Infrastructure Grant for Quality Improvement (SM56618-02) from the Center for Mental Health Services. The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration's Center for Mental Health Services.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Abramson MF: The criminalization of mentally disordered behavior: possible side-effect of a new mental health law. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 23:101–107, 1972Google Scholar

2. Steadman HJ, Vanderwyst D, Ribner S: Comparing arrest rates of mental patients and offenders. American Journal of Psychiatry 135:1218–1220, 1978Google Scholar

3. Rabkin J: Criminal behavior of discharged mental patients: a critical appraisal of the research. Psychological Bulletin 86:1–27, 1979Google Scholar

4. Ribner SA, Steadman HJ: Recidivism among offenders and ex-mental patients. Criminology 19:411–420, 1979Google Scholar

5. Harry B, Steadman HJ: Arrest rates of patients treated at a community mental health center. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 39:862–866, 1988Google Scholar

6. Teplin LA: The prevalence of severe mental disorder among male urban jail detainees: comparison with the Epidemiological Catchment Area program. American Journal of Public Heath 80:663–669, 1990Google Scholar

7. Hiday VA, Swartz MS, Swanson JW, et al: Criminal victimization of persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 50:62–68, 1999Google Scholar

8. Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, et al: Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:911–921, 2005Google Scholar

9. Silver E, Arseneault L, Langley J, et al: Mental disorder and violent victimization in a total birth cohort. American Journal of Public Health 95:2015–2021, 2006Google Scholar

10. Pandiani JA, Banks SM: Large data sets are powerful. Psychiatric Services 54:746, 2003Google Scholar

11. Leginski WA, Croze C, Driggers J: Data Standards for Mental Health Decision Support Systems, Series FN No 10. CR DHHS pub no ADM-89-1589. Washington, DC, US Government Printing Office, 1989Google Scholar

12. National Incident-Based Reporting System Resource Guide. Ann Arbor, Mich, Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research, National Archive of Criminal Justice Data. Available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/nacjd/nibrs/Google Scholar

13. Banks SM, Pandiani JA: Probabilistic population estimation of the size and overlap of data sets based on date of birth. Statistics in Medicine 20:1421–1430, 2001Google Scholar

14. Pandiani JA, Banks SM, Schacht LM: Personal privacy versus public accountability: a technological solution to an ethical dilemma. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 25:456–463, 1998Google Scholar

15. Felson RB, Steadman HJ: Situational factors in disputes leading to criminal violence. Criminology 21:59–74, 1983Google Scholar