Factors Predicting Choice of Provider Among Homeless Veterans With Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Homeless persons with serious mental illness are especially likely to lack access to comprehensive medical and psychiatric care. This study examined the relative importance of predisposing factors, illness factors, and enabling factors as determinants of the use of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care services by mentally ill homeless veterans seeking services from a non-VA program. Predisposing factors included demographic characteristics and wartime service; illness factors were related to the type of medical problem and the need to seek medical care; and enabling factors included entitlement to VA medical services and location of VA facilities. METHODS: Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze data for 698 homeless veterans with mental illness who were enrolled in the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program. RESULTS: About 56 percent of the mentally ill homeless veterans had used VA services at some time in their lives. Homeless veterans were almost twice as likely as other poor veterans to use VA services; those with a dual diagnosis were also more likely to use VA services. Enabling factors were more important than either predisposing or illness factors in predicting VA service use. Veterans most likely to use VA services were those who received VA benefits that gave them priority access to VA services and those who lived near a VA medical center. CONCLUSIONS: Specific characteristics of the service system and of veterans' entitlement were more important than clinical needs or predisposing factors in predicting service use.

As the U.S. health care system experiences a period of unprecedented upheaval, access to health care by persons who are least well off has become a major issue. Homeless persons with serious mental illness are especially likely to lack access to comprehensive medical and psychiatric care (1). Although many studies of service use in this population have been published, few have focused on the choice of provider.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system offers an unusual opportunity to examine the factors associated with the choice of provider in a system that is especially committed to providing benefits to those who need them most. As Wilson and Kizer (2) have noted, "The VA health care system stands out as a significant, coordinated … national safety net for veterans." The VA system is among the largest providers of public mental health care in the United States (3), accounting for 8.6 percent of psychiatric inpatient beds and 8.1 percent of inpatient days in the total supply of psychiatric services (4).

Homeless veterans constitute a substantial proportion of the male homeless population. Estimates indicate that 32 to 47 percent of adult homeless men have served in the armed forces (5,6). Numerous VA programs have been initiated specifically to target homeless veterans (7). However, despite VA attempts to provide psychiatric, substance abuse, and medical health benefits to those who need them, not all eligible veterans, homeless or otherwise, use these services, both because the supply is limited and because some veterans choose not to use them.

Several previous reports have described the use of VA services among subgroups of veterans who were not homeless (4,8,9,10). These studies used a model developed to analyze health care use by the general population that differentiates among the predisposing factors, the illness factors, and the enabling factors associated with the use of health care services (11). Predisposing factors are those that existed before the onset of illness. They include demographic characteristics—gender, race, age, education, and the like—and, among veterans, wartime and war zone service. Illness factors refer to issues ordinarily associated with the need to seek medical services for physical problems or psychiatric or substance use disorders. Enabling factors are circumstances that entitle a person to medical services or encourage the use of medical services. For veterans these include meeting VA eligibility criteria and geographic proximity to a VA medical center where services are available.

In this study we examined the relative importance of predisposing, illness, and enabling factors as determinants of VA service use among homeless veterans currently seeking mental or other health services from a non-VA program.

Methods

We used data from the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program—a five-year, 18-site demonstration program implemented in 1994 and sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services. The two major goals of the ACCESS project were to increase service system integration through site-specific development strategies and to evaluate the impact these strategies had on homeless clients with mental illness (12). The program was not limited to veterans, nor did it especially target them for services. Homeless persons were eligible for services if they suffered from serious mental illness and were not involved in ongoing community treatment. Operational eligibility criteria have been described elsewhere (13).

The program operated in nine states and eighteen communities across the United States: Bridgeport and New Haven, Connecticut; the Edgewater-Uptown and Lincoln Park-Near North areas of Chicago; Sedgwick and Shawnee Counties, Kansas; St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri; Mecklenburg (Charlotte) and Wake (Raleigh) Counties, North Carolina; the West and Center City areas of Philadelphia; Forth Worth and Austin, Texas; Richmond and Hampton-Newport News, Virginia; and the Uptown and Downtown areas of Seattle.

A comprehensive baseline structured interview was administered to new ACCESS participants during each year of rolling enrollment into the program from 1995 to 1998. As part of that interview, participants were asked if they had ever served in the U.S. armed forces. Beginning in the second year, homeless veterans were also administered a special supplemental interview in which they were asked questions about their military experiences including active duty status, era of service, war zone service, type of discharge, receipt of a service-connected disability, receipt of a non-service-connected pension, and use of VA health services. Our sample was a subset of the 698 veterans for whom we had data from the supplemental interview, who served on active duty, and who answered questions about lifetime use of VA services.

The dependent variables of interest concerned the respondents' lifetime use of VA health services as indicated by their responses to the question "Have you ever received health services from a VA medical center?" Veterans who answered in the affirmative were then asked whether the services were for psychiatric, substance abuse, or medical problems.

The independent variables were grouped into three categories: predisposing factors, illness factors, and enabling factors. Predisposing factors included demographic variables such as marital status, gender, age, ethnocultural or racial identity, and years of education. Also included were three variables related to military experiences: Vietnam-era service (August 1964 to April 1975), service in a war zone in Vietnam, and exposure to combat fire.

Illness factors consisted of three subscales of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI), which measures the need for additional treatment for psychiatric, alcohol, or drug problems (14). Higher scores reflect more severe problems. A diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was also included as an illness factor because of its importance to combat veterans. A dual diagnosis—that is, a substance dependence diagnosis along with a mental illness diagnosis—was included for the same reason. A health problems index was constructed by summing positive responses to questions about the current presence of 17 medical conditions: diabetes, anemia, high blood pressure, heart disease, liver disease, arthritis, chest infection, pneumonia, epilepsy, tuberculosis, skin diseases, lice or scabies, physical handicaps, sexually transmitted diseases, teeth problems, gynecological problems, and trauma (fractures, burns, cuts, and wounds). The index ranged from 0 (no problems) to 17 (problems in all areas).

Enabling factors included VA eligibility criteria such as having a VA service-connected disability or a non-service-connected pension. Veterans who do not have a service-connected disability must submit to a means test (15). The VA income means test threshold for a single veteran with no dependents was $20,469 in 1995; virtually all homeless veterans therefore are eligible for free VA services. Thus one of the enabling factor variables was income, measured as the total amount, in dollars, of funds received in the past month from all sources—earned, Supplemental Security Income, illegal, and so on. VA eligibility is also contingent on type of discharge from the military—bad conduct or dishonorable discharge versus honorable, general, medical, or other discharge. Veterans who received bad conduct or dishonorable discharges are not eligible for VA services, although they may use them on an emergency or compassionate basis.

Also included among the enabling factors was residence in a city in which a VA hospital was located. (Six sites that had no hospital were excluded. They were Forth Worth and Austin, Texas; Bridgeport, Connecticut; Sedgwick County, Kansas; and Mecklenburg and Wake Counties, North Carolina).

Chi square and one-way analysis of variance were used to test bivariate associations. Because the dependent variable is a dichotomous variable, we used logistic regression in the multivariate analyses to calculate the likelihood of homeless veterans' ever having used VA services.

Results

The vast majority of the sample (92 percent) were male, and only 6 percent were currently married or remarried. The mean±SD age was 43±8.7 years, and the mean years of schooling was 12.6±2.1. About 49 percent were black, 45 percent were white, 3 percent were Hispanic (regardless of race), and 3 percent were Alaskan Native or American Indian, Asian or Pacific Islander, or other. The mean monthly income from all sources was $336±$413 (median= $240), suggesting a mean annual income of $4,032. Nineteen percent reported no monthly income at all.

In all, 390 veterans (56 percent) responded that they had received services from a VA medical center at some time in their lives. The members of this subgroup were then asked what type of services they had received. Some 83 percent responded that they had used medical services, 77 percent had used psychiatric services, and 50 percent had used substance abuse services.

Since mental illness was a criterion for eligibility in the ACCESS program, all participants had a mental illness. According to their case managers, about 37 percent had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 45 percent major depression, 23 percent bipolar disorder, and 14 percent posttraumatic stress disorder (the categories are not mutually exclusive). About 60 percent had comorbid disorders.

Overall, 306, or 43 percent, had served during the Vietnam era. Of these, 111, or 36 percent, had served in a war zone, and of these, 91, or 82 percent, had been exposed to hostile fire. Twenty-five percent had served in war zones. Only 6 percent of the sample received a bad conduct or dishonorable discharge.

Statistically significant bivariate associations were found in each of the three categories. Among the predisposing factors, we found that, compared with veterans who had never used VA services, VA service users were older on average (44 versus 41 years of age; F=27.25, df=1,695, p<.001), slightly better educated (12.8 years of schooling versus 12.4 years; F=4.33, df=1,694, p<.05), and more likely to be black (54 percent versus 46 percent; χ2=9.21, df=1; p<.01). More VA service users were currently married or remarried than nonusers, although the correlation was not statistically significant. Those who had used VA services also were more likely to have served during the Vietnam era (54 percent versus 31 percent; χ2=35.44, df=1, p<.001) and to have served in a war zone (32 percent versus 16 percent; χ2=23.39, df= 1, p<.001). There were no significant differences between males and females in the use of VAservices.

Several statistically significant associations were found among the illness factors. Veterans who had used VA services were more likely to have a dual diagnosis (64 percent versus 54 percent; χ2=6.81, df=1, p<.01) and a diagnosis of PTSD (18 percent versus 9 percent; χ2=10.97, df=1, p=.001). They also scored higher on the health problems index than nonusers (average of 2.7 problems versus 2.1 problems; F=12.01, df=1,694, p<.001). There were no significant differences between users and nonusers of VA services on any of the three ASI measures or with respect to diagnoses of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression.

With the exception of current income, all of the enabling factors had statistically significant associations with use of VA services. Veterans with service-connected disabilities or non-service-connected VA pensions or those living in cities with VA medical centers or hospitals were more likely to have used VA services. As expected, veterans with bad conduct or dishonorable discharges were less likely to have used VA services.

Because many of the independent variables could be associated with age, we repeated the analyses controlling for age (data not shown). The results did not change, except that the mild correlation between service use and marital status achieved statistical significance.

Predicting use of VA services

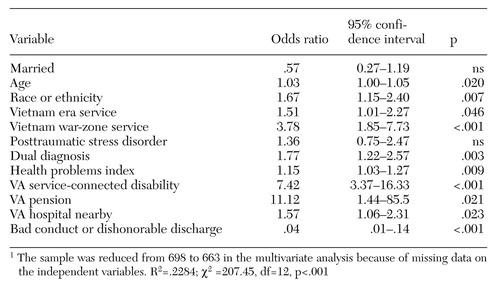

In this section we present the results of logistic regression analyses that identified predictors of ever having used VA services independent of other factors. As shown in Table 1, the strongest predictors were VA service-connected disability and VA pension. Because age was associated with a higher likelihood of having used VA services, it was important to make sure that the observed effects of other variables were not the result of age. For this reason, age functions as a control variable in the multivariate analysis.

Also statistically significant were being black, having served during the Vietnam era, having served in a war zone in Vietnam, and enrollment at an ACCESS site in a city that had a VA medical center. The odds ratio for having served in a war zone in Vietnam was almost 3.8; that is, veterans were 3.8 times more likely ever to have used VA services if they served in a war zone in Vietnam than those who served in other war zones or who did not serve in any war zone. Marital status and having been diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder were not statistically significant predictors of having used VA services. The same holds for diagnoses of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (data not shown).

Receipt of a bad conduct or dishonorable discharge, versus honorable, general, medical, or other discharges, was the only factor in the model that decreased the likelihood of having used VA services when compared with other discharges. The explained variance in the model was 22.8 percent.

Predicting use of specific VA health services

We also used a logistic regression model to analyze the use of different VA health services among the subset of veterans who provided this information (N=390). For use of VA psychiatric services, the only statistically significant variable among the predisposing factors was having served in a war zone in Vietnam. Among the illness factors, as might be expected, only the ASI index was statistically significant as a predictor of use of psychiatric services. Among the enabling factors, VA disability benefits and enrollment at an ACCESS site where a VA medical center was located independently predicted use of psychiatric services.

We also modeled use of VA substance abuse services. Among the predisposing variables, being black and having served during the Vietnam era had statistically significant positive effects on the likelihood of using VA substance abuse services. Among the illness variables, the ASI alcohol score and having a dual diagnosis had strong positive effects. Higher scores on the ASI psychiatric index also were associated with a higher likelihood of using VA substance abuse services, although this association was not statistically significant. Enrollment at an ACCESS site that included a VA medical center was the only statistically significant enabling factor predicting use of substance abuse services.

Finally, we modeled use of VA medical services. No predisposing factor was a statistically significant predictor of the likelihood of using VA medical services. The health problems index was the only illness factor that served as a statistically significant predictor of using medical services. The variable representing a bad conduct or dishonorable discharge was not used because the subset analysis of veterans receiving VA medical services included only four subjects with bad discharges, and they all received medical services, presumably on an emergency or humanitarian basis. The only statistically significant enabling factor was having a service-connected disability.

Discussion

Although a majority (56 percent) of the homeless veterans in the sample had received health services from a VA medical center at some time in their lives, a substantial minority (44 percent) had not. For comparison, it is noteworthy that among veterans in the general population with an estimated annual income of less than $10,000, only 33 percent reported ever having used VA services (16). Thus homeless veterans were almost twice as likely as other poor veterans to have used VA services. From this perspective, VA services appear to be especially accessible and desirable for homeless veterans.

On the other hand, one-fourth of those who had used VA services did not report receiving psychiatric care. Taking into account those who never used any VA services, a majority of this sample of homeless veterans with mental illness never received any VA psychiatric services. The record was somewhat better for veterans with substance use disorders. Of those with drug dependence who had used VA services, 66 percent received substance abuse services. Of those with alcohol dependence who had used VA services, 65 percent received substance abuse services. Thus, although homeless veterans were more likely than other poor veterans to have used VA services, many had not received the specialty services they appear to have needed.

Several other factors had statistically significant relationships with VA service use. Of the predisposing factors, the Vietnam experience was associated with a substantially higher likelihood of VA service use among homeless veterans with mental illness. Rosenheck and Fontana (4) found a similar preference for VA services among Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder in the general population.

We found no evidence of avoidance of VA services by either black or female veterans—two groups often thought to avoid VA services. On the contrary, blacks were significantly more likely than others to have used VA services, and female veterans were as likely as males to use VA services.

Although the ACCESS program's target population was homeless persons with mental illness, we know that homeless people are also subject to a variety of other medical problems (17). In this regard it is encouraging that among homeless veterans who used VA services, medical services were the most frequently reported. In addition, homeless veterans with a dual diagnosis—a group that often has the most difficulty in gaining access to services—were more likely than others in this sample to have used VA services. Future research might include qualitative interviews with veterans to explore why Vietnam veterans and veterans with a dual diagnosis are more likely to use VA services.

As one might expect in respondents with high levels of need, enabling factors were more important than either predisposing or illness factors in predicting VA service use. The veterans most likely to use VA services were those who received VA benefits that gave them priority access to VA health care services and those who lived near VA medical centers.

Although in recent years the availability of VA inpatient substance abuse beds has been gradually reduced (18,19), the overall number of veterans receiving services has not declined, and the number of homeless veterans receiving VA services has increased substantially (20,21). Thus we think the effect of recent changes in the VA system on service use is limited but deserves further study.

Conclusions

Specific characteristics of the service system and of veterans' entitlement are more important in predicting service use by homeless veterans than either clinical needs or individual characteristics. It is well documented that poor people often do not feel as though they have a right to, or are entitled to, the same benefits as others. This study suggests that fostering a sense of such entitlement provides a powerful incentive for them to use needed services. The VA movement to provide outreach assistance to homeless veterans through special mobile teams can be expected to facilitate the use of VA services both by increasing this sense of entitlement and by improving accessibility. VA initiatives may also be able to increase awareness among non-VA providers about eligibility for VA services.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under interagency agreement AM9512200A between the Center for Mental Health Services and the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center as well as by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs in support of the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center at the VA Medical Center in Northampton, Massachusetts. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the late Julie Lam, Ph.D., in the early stages of the data analysis.

Dr. Gamache is a research associate at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and site coordinator of the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of the Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Northampton, Massachusetts. Dr. Rosenheck is director of the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center and professor of psychiatry and public health at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Tessler is associate director of the Social and Demographic Research Institute and professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Address correspondence to Dr. Gamache at the VA Medical Center (12), Upper Leeds, Massachusetts 01053-9764 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Logistic regression analysis of VA service among 663 homeless veterans with mental illness seeking care at ACCESS program sites1

1 The sample was reduced from 698 to 663 in the multivariate analysis because of missing data on the independent variablesR2=.2284; χ2 =207.45, df = 12, p<.001

1. Brickner PW, Scanlan BC: Health care for homeless persons: creation and implementation of a program, in Under the Safety Net: The Health and Social Welfare of the Homeless in the United States. Edited by Brickner PW, Scharer LK, Conanan BA, et al. New York, Norton, 1990Google Scholar

2. Wilson NJ, Kizer KW: The VA health care system: an unrecognized national safety net. Health Affairs 16(4):200-204, 1997Google Scholar

3. Rosenheck R, Stolar M: Access to public mental health services: determinants of population coverage. Medical Care 36:503-512, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Do Vietnam-era veterans who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder avoid VA mental health services? Military Medicine 60:136-142, 1995Google Scholar

5. Rosenheck R, Frisman L, Chung AM: The proportion of veterans among homeless men. American Journal of Public Health 84:466-469, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Leda CA, Frisman LK, et al: Homeless veterans, in Homelessness in America: A Reference Book. Edited by Baumohl J. Phoenix, Ariz, Oryx Press, 1996Google Scholar

7. Rosenheck R, Leda CA, Gallup P: Program design and clinical operation of two national VA initiatives for homeless mentally ill veterans. New England Journal of Public Policy 8:315-337, 1992Google Scholar

8. Rosenheck R, Massari L: Wartime military service and utilization of VA health care services. Military Medicine 158:223-228, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Utilization of health services by minority veterans of the Vietnam era. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:685-691, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Ethnocultural variations in service use among veterans suffering from PTSD, in Ethnocultural Aspects of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Edited by Marsella A, Friedman M, Gerrity E, et al. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1996Google Scholar

11. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly 51:95-124, 1973Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Randolph F, Blasinsky M, Leginski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

14. McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Federal Benefits for Veterans and Dependents. Washington, DC, Department of Veterans Affairs, 1998Google Scholar

16. Veterans' Health Care: Most Care Provided Through Non-VA Programs. GAO/HEHS-94-104BR. Washington, DC, US General Accounting Office, Apr 25, 1994Google Scholar

17. Wright JD: The health of homeless people: evidence from the National Health Care for the Homeless Program, in Under the Safety Net: The Health and Social Welfare of the Homeless in the United States. Edited by Brickner PW, Scharer LK, Conanan BA, et al. New York, Norton, 1990Google Scholar

18. Moos RH, Humphreys K, Ouimette PC, et al: Evaluating and improving VA substance abuse patients' care. American Journal of Medical Quality 14:45-54, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Humphreys K, Huebsch PD, Moos RH, et al: The transformation of the Veterans Affairs substance abuse treatment system. Psychiatric Services 50:1399-1401, 1999Link, Google Scholar

20. Rosenheck R, DiLella D. National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 1998 Report. West Haven, Conn, Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center, Feb 11, 1999Google Scholar

21. Kasprow WJ, Rosenheck R, Chapdelaine JD, et al: Health Care for Homeless Veterans Programs: Twelfth Annual Report. West Haven, Conn, Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center, June 14, 1999Google Scholar