Predictors of Mental Health Service Utilization by People Using Resources for Homeless People in Canada

It is well recognized that homeless or impoverished people have increased need for mental health services in comparison with the general population. Large U.S. studies conducted in the 1980s showed substantial rates of mental health problems in this population: from 19% to 30% for affective disorders and from 11% to 17% for schizophrenia ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 .)

However, despite growing awareness of the need for mental health services in this population, it is generally acknowledged that homeless people continue to have inadequate access to these services ( 9 ). Consequently, rates of mental health problems in this population have not declined and in fact may be increasing. We recently showed that in Montreal and Quebec City, 60% of people using resources for the homeless reported mental disorders at some point in their lifetime, and 72% of this group had experienced serious disorders within the past year ( 10 ). However, 56% of the sample had not received any mental health services in the past year, despite having access to the Canadian health care system, which allows all residents free access to such services. In this study we sought to determine what factors predict the utilization of mental health services by homeless or impoverished people.

Homeless or impoverished people with mental disorders face numerous barriers to receiving appropriate health care. Some barriers come from service providers who are reluctant to treat this type of client ( 11 , 12 ). Other barriers come from the people themselves, who are distrustful about the providers and the authorities ( 13 ). In a well-known study, Appleby and Desai ( 14 ) showed that homeless people with mental illness had lower hospital admission rates than people who were domiciled and mentally ill, that they often left the hospital against medical advice, and that few were referred to long-term facilities.

Underlying these various barriers, it has long been assumed that lack of health care insurance (or lack of economic access to health care) is one of the most important factors influencing the utilization of mental health services by homeless or impoverished people. Homelessness among U.S. patients with serious mental illness has been associated with a lack of Medicaid insurance ( 15 , 16 ), and both Kushel and colleagues ( 17 ) and Wenzel and colleagues ( 18 ) reported that lack of health insurance for homeless people was associated with barriers to mental health care. Rosenheck and Lam ( 19 ) also identified economic factors as an important barrier to mental health services.

As a result of this previous research, much energy and attention have been focused on addressing the mental health needs of this population from the viewpoint of economic access. But what if lack of health care insurance is not the only important barrier to service utilization?

Very little research has been devoted to understanding factors—independent of health insurance barriers—that are associated with the use of mental health services by people who are homeless or impoverished. Our study was conducted in the Canadian setting of universal access to health care, where the study population faced no financial barriers to obtaining mental health care services. Therefore, this analysis may offer a unique view of the situation.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to use Pescosolido's network episode model ( 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ) for such an analysis. This model takes a broad view of the person with mental illness and his or her entry into the health care system. Pescosolido and colleagues ( 23 ) explained that in psychiatry the individual does not always make health-related decisions alone and in a rational manner; the individual is often forced to enter the health care system after actions taken by police officers, judges, or family members. The network episode model proposes a "career" approach to the individual's mental illness, taking events into account in a dynamic manner, while respecting the sequences of those events and the multiple options available at any given point in time. Thus actions and decisions become interwoven in a social process that involves the individual within the network. Action strategies are consequently conceptualized as emerging from a rational process intrinsically linked to the social dimension ( 21 ). The four basic concepts of the network episode model are sociodemographic characteristics, or the background that helps set the trajectory of the illness; illness characteristics, or the diagnoses; illness history, or the entrances and exits from the health care system based on diagnoses and remissions; and social network, or the size and function of the individual's social network and his or her satisfaction with this support. All of these elements are believed to interact dynamically to influence each other.

Methods

Sample and data

Our study is a subanalysis of a larger health survey of people using resources for the homeless (N=757) in Montreal and Quebec City, the two largest cities in Canada's province of Quebec ( 10 ). The survey, which was approved by Santé Québec's Research and Ethics Board, measured utilization of resources for homeless people in 17 shelters, seven soup kitchens, and 12 day centers over a nine-month period between 1998 and 1999. Resource utilization was measured according to person-days, defined as the use of at least one resource by one person on a given day. A stratified random sample was established according to a preliminary census of all the resources of the two cities. In total, 1,168 people were approached to be interviewed, and 757 of them agreed. No exclusion was made on the basis of residential status, such that individuals could either have had a fixed address or not at the time of the study.

Sample weighting was established by the Statistical Institute of Quebec in order to take into account the sample design and the absence of participants for some days. Thus a weight was attributed to each person to quantify the number of people each represented within the target population, making it possible to create valid estimates for the whole population. The unweighted response rate was 71%.

We used data from a subset of 439 people who met DSM-IV criteria for affective disorders (major depression or dysthymic disorder) or axis I psychotic disorders (schizophrenia or other psychoses). People with substance disorders only or personality disorders only were not included in this sample. However, people with concomitant axis I disorders and substance disorders or personality disorders were included, because past research has shown a substantial comorbidity in this population. All of the participants were using resources for the homeless at the time of the study, but not all of them were necessarily homeless themselves. This entry criterion was chosen intentionally to enable a comparison of homelessness per se versus poverty alone and how these different factors influence service utilization. It can be assumed that all participants using resources for the homeless were impoverished.

Interviews were conducted with the study participants by 16 research assistants who were recruited on the basis of either their professional experience as interviewers or their experience with the population concerned. The interviewers received a 50-hour training course on how to use the data-gathering instruments, particularly the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS-IV). Interviews were carried out face to face, usually took place in the resource center, and lasted approximately two hours. A pretest was carried out over a one-week period in order to check the clarity of the questions, evaluate the duration of interviews, and test the data acquisition procedures. In addition to information about gender, age, and housing status, the interviews gathered information in the following areas.

Utilization of mental health services. For measuring utilization, we used the questionnaire developed by Fournier ( 24 ), based on the work of Farr and colleagues ( 25 ), Morse and colleagues ( 26 ), and Roth and colleagues ( 27 ). This questionnaire has been previously validated with homeless people. It has three parts: one concerning hospitalizations, one concerning other service utilization, and the last concerning treatment related to substance use disorders. After analysis of the data, it was evident that people using one of these services were very often using at least one other. Thus we chose to link all of these services into one dichotomized variable for logistic regression analysis.

Mental disorders. We assessed mental disorders with the DIS-IV ( 28 ). Only the following sections of this instrument were used: schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorders, schizoaffective disorders, affective disorders (major depression, dysthymic disorders, hypomania, mania, and bipolar I and II disorders), antisocial personality disorders, and pathological gambling. Validity and reliability of the DIS have been reported elsewhere ( 29 , 30 , 31 ). We specified whether participants had experienced the mental disorder within the past 12 months, before this period, or never, because it is now recognized that even though certain mental health problems may appear to be chronic, some people with schizophrenia can have a spontaneous recovery ( 32 ) and about 50% of people with antisocial personality disorder experience a significant improvement or remission by the time they reach their 40s and 50s ( 33 ).

Substance-related disorders. We measured these disorders with the International Diagnostic Interview Simplified ( 34 ). We used the most recent version in order to apply DSM-IV criteria. This new version was not validated, but the preceding one, based on DSM-III-R, had been validated ( 35 ).

Social support. We used the Arizona Social Support Schedule Interview ( 36 ), which allowed us to measure the size and function of social networks and participants' satisfaction with this support.

Analyses

Data collected from the interviews were organized, using hierarchical logistic regression analysis, into the corresponding network episode model concepts, namely sociodemographic characteristics, illness characteristics, illness history, and social network. The dependent variable was utilization of one service or another during the 12 months preceding the interview. SPSS version 14.0 was used for data analysis, and the significance level for the Wald chi square statistic was set at p<.10 ( 37 ). We used the "enter" method, in which all variables, significant or not, are kept at each stage of the analysis. Bivariate analysis was performed before this process in order to keep a minimum number of variables and to detect multicollinearity ( 37 ). Dummy variables were created for categorical variables. Only the variables significantly associated with mental health service utilization were kept for regression analysis.

Results

A majority of the sample (84%) was male ( Table 1 ), and only 2% were currently married. The mean±SD age was 41±12 years; 296 (93%) were born in Canada; and there were three African Americans, three Hispanics, and three First Nations people (totaling 3%). A little more than one-third were homeless at the time of the interview, but nearly half of the population had been homeless previously. In terms of psychiatric diagnoses, two-thirds had affective disorders, and in addition to their main mental health disorders, one-third had antisocial personality disorders, whereas more than half had substance-related disorders. Forty-one percent had been hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder in the preceding year. The mean size of the participants' social support network was about three people, with few of the support people being resource users themselves.

|

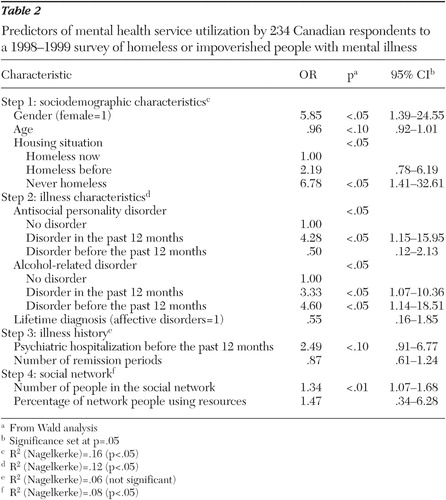

Table 2 shows that each network episode model concept except illness history significantly predicted utilization of mental health services. Moreover, all the predictors within each network episode model concept were significantly relevant to utilization, and these predictors remained significant when other predictors were added.

|

Our study revealed that female gender, younger age, never being homeless, presence of antisocial personality disorder in the past 12 months, past or current alcohol-related disorders, hospitalization within the past 12 months, and a larger social support network were related to greater utilization of mental health services ( Table 2 ). Thus, only lifetime diagnosis and number of remissions failed to remain significant.

Discussion

This study is one of the largest ever done in Canada. It used a rigorous sampling method based on a census in order to reach most of the population that uses resources for the homeless in Montreal and Quebec City.

By studying Canadians' use of mental health resources for homeless and impoverished people, in a country where access to health care is free to all citizens, we have confirmed that previously identified predictors of service utilization remain important. One may question our decision to dichotomize the outcome variable for service utilization, because this variable can comprise different types of services. In fact, when we considered all of our service variables, we noticed that most participants had used more than one service during his or her lifetime or during the past year. Very often all of these services are part of a continuum and are offered by one resource, which then refers a patient to another. Thus one person can be seen, for example, at an emergency unit and be transferred to a community resource or be hospitalized or, conversely, may be followed by the same doctor all this time. Moreover, we demonstrated that people with concurrent mental health and substance abuse disorders used almost the same services that persons with only mental health disorders used ( 38 ).

This study was the first to use the network episode model to identify these predictors. We found that all of the model's concepts except illness history were significantly related to utilization of mental health services. Illness history is undoubtedly the hardest to measure in this type of analysis. In our study, some variables reflecting the illness history, like medication compliance, could not be included in the regression analysis without creating an effect of collinearity with other variables. This concept will need more research in order to be better explained.

Only a handful of studies have used a model to analyze the use of mental health services by homeless or impoverished people. Using the Andersen-Newman model ( 39 ), Padgett ( 40 ) identified education, depressive symptoms, previous psychiatric diagnoses, previous psychiatric hospitalizations, and medical conditions as the main factors associated with service use. Other factors that have been identified with use of services include schizophrenia, lack of co-occurring substance use disorders, acknowledgment of a mental health problem, and having received mental health advice from outside the formal system ( 41 ). In addition, both Wenzel and colleagues ( 42 ) and Gamache and colleagues ( 43 ) used the Andersen-Newman model to study homeless veterans and found that inpatient service use was related to the number of lifetime psychiatric symptoms, substance use disorders during the past year, and not sleeping outdoors or in public spaces. Outpatient service utilization was predicted only by psychiatric symptoms and evidence of liver dysfunction.

Our study confirms several of the findings of these studies in identifying the predictors of mental health service use by homeless people. However, unlike ours, the other studies were not conducted in the context of universal access to health care, making it difficult to assess the importance of each predictor independently. As a result, the interpretation of these previous findings may have attached a disproportionate amount of importance to issues of economic access to health care, with less focus on other potential barriers to access.

Our unique view of the use of mental health services in a free health care system confirms the presence of noneconomic barriers for people who are homeless or impoverished. We hope this important insight will allow the field to progress to a new level of understanding regarding this complex issue.

The findings of this study can be used to identify and target the underserved population but may also help community workers recognize and retain people who are being successfully served. We found that being a woman predicted utilization of services. Because women with mental health disorders are often victims of assault ( 44 ), our findings underscore the importance of creating and maintaining resources that can ensure their security. There is also evidence, from the aforementioned authors, that women are more distressed than men by their mental disorders. Therefore, we suggest that it is also important to create multidisciplinary teams to help homeless or impoverished women reintegrate into normal life.

Our study indicated that people with mental disorders and co-occurring substance abuse or antisocial disorders utilize more services. Hwang and colleagues ( 8 ), Canadian researchers, found that coordinated treatment programs designed to meet the needs of homeless people are effective in reducing alcohol and drug use. It may seem surprising that we found that antisocial personality disorder was associated with increased use of services, given that this population is known to reject authority. However, Booth and colleagues ( 45 ) found that persons with substance use and antisocial personality disorders had more negative treatment results, leading to more intensive utilization of services. Our findings point to the need for more efficient and perhaps more integrated services to help this clientele who have multiple problems.

Our study also identified people who are least likely to seek care—namely men, older people, those without a fixed address, and those with small support networks. Brandt ( 46 ) noted that because these patients are reluctant to have contact with services, it is very easy to forget them on the street. And Dixon and colleagues ( 47 ) suggested that programs can be adapted for this clientele with a specific focus on their social network. Indeed, according to Denoncourt and colleagues ( 48 ), people with serious mental disorders are often introduced to the outreach team by other workers or other homeless people.

Although the data were collected some time ago, between 1998 and 1999, as far as we know, there has been little change in the situation of this population since then. However, one limitation is that we did not interview people living exclusively on the streets, who have no contact with resources, and who make up 10% of the homeless population, according to the census. Toro and Warren ( 49 ) found that people on the streets remain homeless longer. However, Hannappel and colleagues ( 50 ) found no difference between the homeless using resources and those on the streets in terms of sociodemographic characteristics, psychological distress, and hospitalizations.

Another limitation of our study is that some people were unable to finish the questionnaire. We can assume that these people probably had more severe mental disorders or substance-related disorders, but our analyses showed that their exclusion did not significantly change our results. It is possible that our study's unique context of free access to health care services may itself influence mental health service utilization. For example, previous research ( 51 ) in the setting of economic barriers to health care has found that co-occurring mental health disorder and substance abuse are associated with less utilization of services, whereas our study found these factors were related to more use of services. Perhaps, as suggested by Bland and colleagues ( 52 ), in a system where everyone has equal rights to health care services, the more diagnoses an individual has, the more likely the person is to ask for services.

Conclusions

This study is the first to use the network episode model to identify predictors of mental health service utilization by people using resources for the homeless in a universal-access health care system. It shows that even within this context, predictors of service utilization are congruent with what has been previously identified with the use of other models. In addition, our findings suggest that contrary to previous assumptions, money may not necessarily be a barrier in utilization, or access to services might not be sufficient. Therefore, focusing on the factors we have identified may be a better strategy in devising improved mental health services for this population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grants from the Institut de la Statistique du Québec (Dr. Fournier) for the data collection and by Fonds de recherche en Santé du Québec for the writing of the article.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Koegel P, Burnam M, Farr RK: The prevalence of specific psychiatric disorders among homeless individuals in the inner city of Los Angeles. Archives of General Psychiatry 45:1085–1092, 1988Google Scholar

2. Vernez G, Burnam MA, McGlynn EA, et al: Review of California's Program for the Homeless Mentally Disabled. Los Angeles, RAND Corp, 1988Google Scholar

3. Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Kramer M, et al: Health and mental health problems of homeless men and women in Baltimore. JAMA 262:1352–1357, 1989Google Scholar

4. Susser EA, Struening EL, Conover S: Psychiatric problems in homeless men: lifetime psychosis, substance use, and current distress in new arrivals at New York City shelters. Archives of General Psychiatry 46:845–850, 1989Google Scholar

5. Donohoe M: Homelessness in the United States: History, Epidemiology, Health Issues, Women, and Public Policy, 2004. Available at www.medscape.com/viewarticle/481800Google Scholar

6. World Health Organization: How Can Health Care Systems Effectively Deal With the Major Health Care Needs of Homeless People? Geneva, World Health Organization Europe, 2005Google Scholar

7. Folsom D, Jeste DV: Schizophrenia in homeless persons: a systematic review of the literature. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 105:404–413, 2005Google Scholar

8. Hwang S, Tolomiczenko G, Kouyoumdjian F, et al: Interventions to improve the health of the homeless: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29:311–319, 2005Google Scholar

9. Gallagher TC, Andersen RM, Koegel P, et al: Determinants of regular source of care among homeless adults in Los Angeles. MedCare 35:814–830, 1997Google Scholar

10. Fournier L: Montreal Centre and Quebec's Resources for Homeless People Survey: 1998–1999 [in French]. Montreal, Institut de la Statistique du Québec, 2001Google Scholar

11. Chafetz L: Withdrawal from the homeless mentally ill. Community Mental Health Journal 26:449–461, 1990Google Scholar

12. Cohen NL: Stigma is in the eye of the beholder: a hospital outreach program for treating homeless mentally ill people. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic 54:255–258, 1990Google Scholar

13. Breakey WR, Fischer PJ, Nestadt G, et al: Stigma and stereotype: homeless mentally ill persons, in Stigma and Mental Illness. Edited by Fink PJ, Tasman A. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1992Google Scholar

14. Appleby L, Desai PN: Documenting the relationship between homelessness and psychiatric hospitalization. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:732–737, 1985Google Scholar

15. Stark LR: Counting the homeless: an assessment of S-Night in Phoenix. Evaluation Review 16:400–408, 1992Google Scholar

16. Folsom DP, Hawthorne W, Lindamer L, et al: Prevalence and risk factors for homelessness and utilization of mental health services among 10,340 patients with serious mental illness in a large public mental health system. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:370–376, 2005Google Scholar

17. Kushel MB, Vittinghoff E, Haas JS: Factors associated with the healthcare utilization of homeless persons. JAMA 285:200–206, 2001Google Scholar

18. Wenzel SL, Leake BD, Gelberg L: Risk factors for major violence among homeless women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 16:739–752, 2001Google Scholar

19. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381–386, 1997Google Scholar

20. Pescosolido BA: Beyond rational choices: the social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology 97:1096–1138, 1991Google Scholar

21. Pescosolido BA: Illness careers and network ties: a conceptual model of utilization and compliance. Advances in Medical Sociology 2:161–184, 1992Google Scholar

22. Pescosolido BA: Bringing the "community" into utilization models: how social networks link individuals to changing systems of care. Research in the Sociology of Health Care 13A:171–197, 1996Google Scholar

23. Pescosolido BA, Gardner CB, Lubell KM: How people get into mental health services: stories of choice, coercion and "muddling through" from "first timers." Social Science and Medicine 46:275–286, 1998Google Scholar

24. Fournier L: Homeless and Mental Health in Montreal: Descriptive Study of Mission and Shelter's Clientele [in French]. Verdun, Québec, Unité de Recherche Psychosociale, Centre de Recherche de l'Hôpital Douglas, 1991Google Scholar

25. Farr RK, Koegel P, Burnam A: A Study of Homelessness and Mental Illness in the Skid Row Area of Los Angeles. Los Angeles, Department of Mental Health, 1986Google Scholar

26. Morse G, Shields NM, Calsyn RJ, et al: Homeless People in St. Louis: A Mental Health Program Evaluation, Field Study, and Follow-up Investigation. Jefferson City, Mo, Department of Mental Health, 1985Google Scholar

27. Roth D, Bean J, Lust N, et al: Homelessness in Ohio: A Study of People in Need. Columbus, Ohio Department of Mental Health, 1985Google Scholar

28. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381–389, 1981Google Scholar

29. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Ratcliff KS, et al: Validity of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version II: DSM-III diagnoses. Psychological Medicine 12:855–870, 1982Google Scholar

30. North CS, Pollio DE, Thompson SJ, et al: A comparison of clinical and structured interview diagnoses in a homeless mental health clinic. Community Mental Health Journal 33:531–543, 1997Google Scholar

31. Helzer JE, Robins LN, McEvoy LT, et al: A comparison of clinical and diagnostic interview diagnoses. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:657–666, 1985Google Scholar

32. Lalonde P: Schizophrenias, in Clinical Psychiatry: Bio-Psycho-Social Approach, vol 1 [in French]. Edited by Lalonde P, Aubut J, Grundberg F. Montréal, Quebec,Morin, 1999Google Scholar

33. Black C: Antisocial personality disorder: the forgotten patients of psychiatry. Primary Psychiatry 8:30–81, 2001Google Scholar

34. Kovess V, Fournier L: The DISSA: an abridged self-administered version of the DIS—approach by episode. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 25:179–186, 1990Google Scholar

35. Kovess V, Fournier L, Lesage A, et al: Two validations of the CIDIS: a simplified version the CIDI. Psychiatric Networks 4:10–24, 2001Google Scholar

36. Barrera M Jr: A method for the assessment of social support networks in community survey research. Connections 3:8–13, 1980Google Scholar

37. Hosmer D, Lemeshow S: Applied Logistic Regression. New York, Wiley, 1989Google Scholar

38. Bonin JP, Fournier L, Blais R et al: Utilization of Services by People With Concurrent Mental and Substance Abuse Disorders Going to Resources in Montreal and Quebec [in French]. Drogue, Santé et Société 4:211–248, 2006Google Scholar

39. Andersen R, Newman JF: Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States., Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly/Health and Society 51 Winter:95–124, 1973.Google Scholar

40. Padgett DK, Struening EL, Andrews H: Factors affecting the use of medical, mental health, alcohol, and drug treatment services by homeless adults. Medical Care 28:805–821, 1990Google Scholar

41. Stein JA, Andersen RM, Koegel P, et al: Predicting health services utilization among homeless adults: a prospective analysis. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and the Underserved 11:212–230, 2000Google Scholar

42. Wenzel SL, Bakhtiar L, Caskey NH, et al: Predictors of homeless veterans' irregular discharge status from a domiciliary care program. Journal of Mental Health Administration 22:245–260, 1995Google Scholar

43. Gamache G, Rosenheck RA, Tessler R: Factors predicting choice of provider among homeless veterans with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1024–1028, 2000Google Scholar

44. Roll CN, Toro PA, Ortola GL: Characteristics and experiences of homeless adults: a comparison of single men, women, and women with children. Journal of Community Psychology 27:189–198, 1999Google Scholar

45. Booth BM, Blow FC, Ludke RL, et al: Utilization of acute inpatient services for alcohol detoxification. Journal of Mental Health Administration 23:366–374, 1996Google Scholar

46. Brandt P: Schizophrenia and homelessness our demand for efficiency will turn the hardest hit into outcasts. Prelapse Magazine, no 2, Sept 1995. Available at www.mentalhealth.com/mag1/pre-hom1.htmlGoogle Scholar

47. Dixon LB, Krauss N, Kernan E, et al: Modifying the PACT model to serve homeless persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:684–688, 1995Google Scholar

48. Denoncourt H, Desilets M, Plante MC, et al: Outreach Practice for Homeless People With Severe and Persistent Mental Disorders: Observations, Reality and Constraints [in French]. Santé Mentale au Québec 25:179–194, 2000Google Scholar

49. Toro PA, Warren MG: Homelessness in the United States: policy considerations. Journal of Community Psychology 27:119–136, 1999Google Scholar

50. Hannappel M, Calsyn RJ, Morse GA: Mental illness in homeless men: a comparison of shelter and street samples. Journal of Community Psychology 17:304–310, 1989Google Scholar

51. Koegel P, Sullivan G, Burnam A, et al: Utilization of mental health and substance abuse services among homeless adults in Los Angeles. Medical Care 37:306–317, 1999Google Scholar

52. Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H: Help-seeking for psychiatric disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 42:935–942, 1997Google Scholar