Use of VA Aftercare Following Military Discharge Among Patients With Serious Mental Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the use of Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) aftercare services among patients with serious mental disorders who were discharged from the military after a first admission to a Department of Defense (DoD) hospital. METHODS: Administrative data from the DoD and VA health systems were linked to identify active-duty servicemen and -women who were hospitalized in a military hospital with a diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia between 1993 and 1996 and who were subsequently discharged from the military. Split population survival analysis was used to examine separately the correlates of contact with VA outpatient mental health services and, among those who had contact, the time to contact after military discharge. RESULTS: Fifty-two percent of 2,861 identified individuals had received outpatient care from VA mental health clinics by the end of September 1998. The rate of contact was lower than in virtually all studies of aftercare following hospital discharge. Women, older persons, and persons with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were more likely to contact VA outpatient mental health services than men, younger persons, and those with major depression. Among those who made contact, older persons had a longer time to contact. CONCLUSIONS: Many people who leave the military because of serious mental illness do not receive aftercare from the VA. The reasons for such low rates of contact are not clear. Identifying patients who need aftercare but do not receive it and ensuring that they have access to needed services remains an important challenge for the DoD and the VA.

Along with underfunding, fragmentation is widely perceived as the most salient feature of the U.S. health care system. It is easy for patients to lose their way in the system's administrative maze and thus to never receive needed care or to experience discontinuities and delays in care. The problem is accentuated when patients' care is transferred from one system of care to another.

A case in point is the transition of care across the two major federally financed systems in the United States: the health care systems of the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). For most nonretirees who leave the military because of service-related illnesses, the VA health care system is the primary provider of health services. Although both health care systems provide high-quality care for their patients, neither has clear responsibility for individuals who have left the military but have not yet contacted the VA system. As a result, many of these patients could experience discontinuities or delays in needed care.

Such discontinuities are more critical for patients with chronic disorders that require long-term management, as is the case with most mental disorders. For civilian populations with severe mental illness, the transition from institutional care to aftercare in the community presents a critical juncture during which the risk of disruption in various needed services is high (1,2). Individuals who are discharged from the military face the added challenges of moving to a different part of the country after discharge, finding a new job, and establishing new links with the community.

In this cohort study we used administrative data from the DoD and the VA health care systems to examine the extent and correlates of contact with VA outpatient mental health services among persons who were discharged from the military after hospitalization with a diagnosis of major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Although many of these patients might have been stable and asymptomatic at the time of military discharge, there is a consensus that patients who have these diagnoses need aftercare following remission of the initial episode (3).

We also focused on gender and race or ethnicity as potential barriers to seeking VA services. A majority of the patients in the VA system are white men, and the possibility of underuse of mental health services by women and by persons from racial or ethnic minorities has been of particular concern. Although these concerns have been allayed to some extent by reports of similar rates of use of VA services by gender and by race or ethnicity (4,5,6), no studies have examined the association of gender and minority status with the successful transition from the DoD system of care to the VA.

We used the method of split population survival analysis, which separately models contact with services and time to contact and produces separate regression equations for each. This method has advantages over conventional survival analysis methods for analyzing patients' transition from one health service to another when a large proportion of the patients who leave one service never make the transition to the other.

Methods

Sample

The sample for this study was drawn from the National Collaborative Study of Early Psychosis and Suicide, a collaboration between the National Institute of Mental Health, the DoD, and the VA (7). The sample comprised U.S. Armed Forces personnel who had their first admission for major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia to a DoD hospital between 1993 and 1996 and who were subsequently discharged from military service. All patients were on active duty at the time of their hospitalization. To ensure that the study participants were eligible for VA services, the sample was further limited to those who had at least two years of active-duty service before discharge. Thus defined, the sample for this study included 2,861 servicemen and servicewomen.

Diagnostic data were based on the diagnosis at discharge from the last DoD hospitalization, because some of these patients required a number of short hospitalizations before separation from the military. Because distance between residence and VA health facilities is an important predictor of use of VA health services (8), we included this variable in the analyses. Distance was calculated by using a participant's ZIP code at the time he or she entered military service. Information on the ZIP code to which the study participants were discharged after leaving the military was not available.

VA service use data came from the VA Patient Treatment File and the Outpatient Care File, which documented outpatient visits and inpatient admissions up to September 30, 1998. DoD and VA files were linked by using patient identifiers, which were stripped from the files after the linking process to maintain patients' anonymity. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Mental Health, and the researchers received clearance from the health affairs office of the Pentagon and from the VA to receive the data.

Data analysis

We initially intended to use the conventional survival analysis methods to analyze time to contact with VA outpatient mental health services. However, on examining the data, we noted that a large proportion of the patients never contacted these services. Such a pattern implies that the sample was heterogeneous, comprising a subgroup of patients who would eventually contact VA outpatient mental health services after military separation and another subgroup who would never use VA services, even if they were followed up for a long time (9,10).

Although conventional survival methods such as Cox proportional hazards regression analysis can be used for samples including such patients, these methods cannot separate the predictors of contact versus no contact from the predictors of time to contact among patients who do contact services. These two processes may have very different correlates. For example, failure to contact services might be due to dropping out of treatment or to having alternative sources of care, whereas time to contact may be related to the severity of illness or to accessibility of services.

Various survival analysis methods specifically designed for such data have been proposed (9,11,12,13). In the study reported here, we used the split population method proposed by Schmidt and Witte (13,14). The term "split population" implies that the sample comprises two distinct subgroups: persons who would eventually experience the outcome of interest—in this case, contact with VA outpatient mental health services—and those who would not. Thus the model estimates two separate regression equations simultaneously: a logit equation for predictors of contact versus no contact, and a parametric (Weibull) survival equation for time to contact among persons who do contact services. We used the statistical package LIMDEP 7.0 (15) to conduct these survival analyses.

The regression coefficients obtained in the split population survival analysis have the same interpretation as in usual logit and survival analyses. Thus, when exponentiated, the logit coefficients are interpretable as odds ratios and the survival analysis coefficients as hazard ratios. The analyses were conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the bivariate association of each predictor variable with the outcomes of interest—contact and time to contact—was assessed. To examine whether the associations of variables identified in the bivariate analyses were independent of each other or were better explained by other variables, we also conducted a multivariate analysis. Variables associated with either of the outcomes in the bivariate split population analyses at a p value of less than .05 were entered into a multivariate split population model to assess the independent contribution of each, with the other variables in the model adjusted for. A p value of .01 or less was adopted as the criterion for statistical significance in all analyses.

Results

VA outpatient mental health contact

Overall 1,486 (52 percent) of the 2,861 patients had sought care through VA outpatient mental health services by September 30, 1998. The median follow-up period was 14 months but was much longer for patients who separated from the military in earlier years (with a maximum of 81 months).

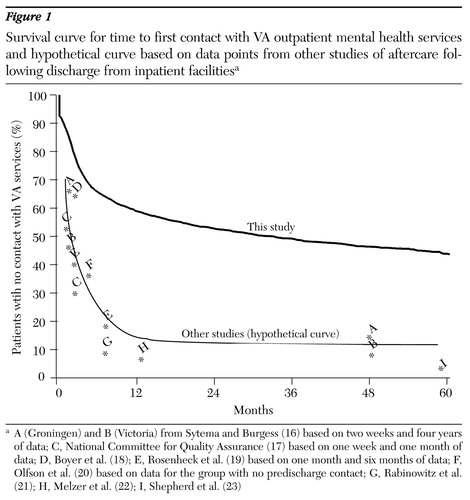

A total of 211 patients (7 percent) contacted VA mental health services before separation from the military. No significant differences in the rate of such contacts were observed across the four military service branches. Including these contacts, a cumulative total of 230 (8 percent) of the total sample had contacted VA outpatient mental health services by one week after separation, 344 (12 percent) by one month, 1,023 (36 percent) by six months, and 1,211 (42 percent) by one year. Time to first use of VA outpatient mental health services is further depicted by a survival curve in Figure 1. (The plateau in the curve reflects the fact that a large proportion of patients did not contact VA outpatient mental health services.)

Correlates of first VA outpatient contact

Because split population survival analysis uses the same model to produce two regression equations, it allows the association of variables with contact and time to contact to be examined separately with the same model.

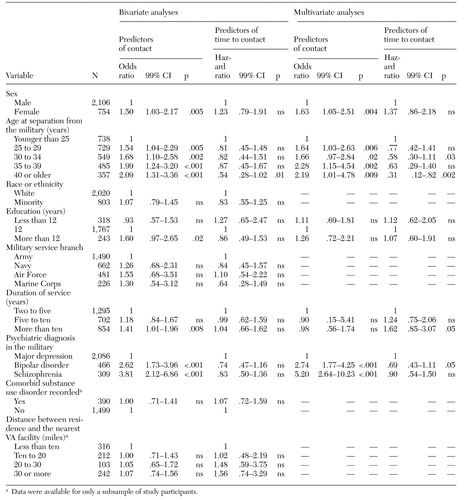

In the bivariate split population analyses (Table 1), being female, being older than 25 years at military separation, having served for more than ten years, and having a diagnosis of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia were predictors of contacting services. Also, patients with more education were more likely to contact VA services, although not at the statistically significant level. Race or ethnicity, military service branch, comorbid substance abuse, and distance between residence and the nearest VA facility were not significant correlates of contact. In the bivariate split population analyses for time to contact, only age was a significant correlate. Study participants who were aged 40 years or older at separation from the military tended to take longer to contact VA outpatient mental health services.

In the multivariate split population analyses, the association between contact and gender, age, and diagnosis persisted in the logit equation. However, duration of service and education were not significant predictors of contact. Age was also significant in the survival regression equation for time to contact that was produced in the same split population model. None of the other variables were significantly associated with time to contact.

Discussion and conclusions

Overall, only slightly more than half of the patients in this study who were hospitalized with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia in DoD hospitals used VA outpatient mental health services after their separation from the military. To put this finding in context, we reviewed the results of a number of studies of aftercare following psychiatric inpatient discharge conducted at different times postdischarge and in various settings (16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23).

It is not possible to examine the survival distribution of time to contact for each of these studies. However, we were able to draw a hypothetical line through these data points (hypothetical curve in Figure 1), which serves as a benchmark for the results of the study reported here. These studies, which were based on national registries or patient follow-up, all recorded higher rates of posthospital aftercare than were found in our study.

In the absence of any information on almost half of the sample, we can only speculate as to plausible explanations for the low rates of outpatient VA mental health contacts we observed.

One explanation is that after separation, some of these patients quickly obtained employment and medical insurance through their new jobs and thus had access to other systems of care. The association of age and diagnosis with the use of VA outpatient mental health services supports this hypothesis. Older persons and those with more severe and impairing illnesses, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, are less likely to obtain employment after separation from the military. Substitution of non-VA services for VA services has been documented in surveys of veterans, especially among those with less severe and nonpsychotic conditions (8,24), which further supports the explanation that patients had access to other systems of care.

Another possible explanation for the low rates of contact with VA outpatient mental health services in this sample is the use of other services because they are more accessible. The per capita supply of VA health services is about a third of that of non-VA services (6,25), and VA facilities are on average less accessible geographically. Although we found no association between geographic distance and service use, our data on geographic distance were based on premilitary ZIP codes, which do not necessarily reflect a patient's current residence. Furthermore, these data were not available for all patients. Future research is needed to investigate the impact of distance and of other accessibility factors, such as urban versus rural settings and VA service capacity in various regions. Capacity may in turn depend on regional VA spending.

Finally, it is possible that some eligible veterans who are in need of aftercare are not receiving any services at all. Currently no mechanisms are in place to monitor the transition of veterans into the community, and, as a result, many can experience discontinuity in care. We discuss issues of tracking and monitoring of this population in the section on policy implications below.

Similar to other studies of veteran populations (5,6,26), our study found no evidence that women and persons from racial or ethnic minorities use VA services less frequently than white men do. Although there is some evidence that persons from racial or ethnic minorities may have less access to other services and hence may use VA services by default (27), this possibility cannot explain the higher rates of service use among discharged servicewomen in our study. Even though female veterans have higher incomes than male veterans and are more likely to have medical insurance (4), they were still more likely than men to use VA services.

Limitations

The limitations of the data we used and the limitations of administrative data in general should be considered in the interpretation of our results. First, as noted, we had no information on the use of non-VA mental health services in this cohort. Thus, although we know that 48 percent of these ill individuals were not receiving mental health care through the VA, we do not know what proportion were receiving care from other sources and what proportion were receiving no care at all. Furthermore, errors in administrative data are common.

Second, in addition to the 1,486 patients who sought care at VA outpatient mental health services, 313 (11 percent) sought care only through VA outpatient general medical services. Some of these patients may have received care for their mental health conditions during some of these visits. When we repeated the analyses and included all outpatient contacts—mental health as well as general medical—the results were similar to those for outpatient mental health contacts (data not shown).

Third, it is possible that some of the patients did not truly have a serious mental disorder but were experiencing adjustment reactions that quickly resolved after discharge from the military. Some may even have been malingering. Patients who have less serious symptoms after discharge from the military are less likely to seek care or to be granted service-connected disability status and become eligible for VA services. We did not have information on service-connected disability status. However, we were able to compare the DoD hospital diagnoses in a sample of 71 hospitalized patients with these patients' medical board diagnoses—which are based on interviews by three psychiatrists and chart reviews—and with the consensus diagnoses of two independent psychiatrists who were blinded to hospital and medical board diagnoses. Hospital diagnoses corresponded perfectly (100 percent) with the medical board diagnoses and corresponded very closely with independent psychiatrists' diagnoses (88 percent, kappa=.84), thus supporting the reliability of the diagnoses used in this study.

Finally, our results predate a number of new system-level initiatives in the VA health care system that could have an impact on mental health services. These initiatives include the implementation of the Veterans Integrated Service Networks, passage of the Veterans Eligibility Reform Act of 1996 (28), and the establishment of community-based outpatient clinics, which are mandated to provide mental health services. Future studies will need to assess the impact of these initiatives on the transition of care from the DoD to the VA health system.

Implication for services and research

The transition to community life after discharge from a first psychiatric hospitalization is often challenging. The problem is compounded when the transition to aftercare also involves a transition across the boundaries of different health care systems. Continuity in health services during the transition from the DoD to the VA was a focal point of a 1999 report by the Congressional Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance (29). The report emphasized the economic and human costs of the current state of unintegrated service systems and proposed that both systems be restructured through partnership. This restructuring would involve the exchange of clinical, management, and financial information and the consolidation of funding and administrative infrastructures that would facilitate transition form the military to civilian life.

Linking administrative data from two systems of care, as we did in this study, has the potential to provide information about the extent and speed of transition from one system of health care to another as well as the correlates of such a transition. However, the results of this study also highlight the significant limitations of administrative data. The data we used provided no information about the fate of a large proportion of patients who exited the DoD health care system but never entered the VA system. In the absence of such information, no conclusions about the service use patterns of this population can be drawn with confidence.

In countries that have centralized health care systems, health care registries provide powerful tools for tracking patients and assessing service use patterns (16). No such national registries exist in the United States. Only by linking service use data from all public and private health care systems could we approximate such national registries and assess individual patients' treatment paths and the continuity of care across different health care systems. However, such linking of databases raises issues of confidentiality—and, in the case of private institutions, proprietary issues—and thus would be extremely difficult.

In the absence of a unified service use data system, the continuous monitoring of the transition processes may require periodic mail-in surveys and prospective follow-up of individual patients. Information obtained through these methods could be used to identify patients who are not receiving needed aftercare services. Focused outreach programs and more-active models of case management (1) could then be used to help these individuals identify and gain access to resources in their communities.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Mojtabai's work was partly supported by grant K01-MH-01754 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a Young Investigator Award from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression. The authors thank Wei-Yann Tsai, Ph.D., and John Bartko, Ph.D., for statistical advice and Ioline Henter, M.A., for comments on an earlier version of this article.

Dr. Mojtabai is affiliated with the department of psychiatry of the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute in New York City. Dr. Rosenheck is with the department of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center in West Haven. The late Dr. Wyatt was with the neuropsychiatry branch of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Susser is with the department of epidemiology of the Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute. Send correspondence to Dr. Mojtabai at 2600 Netherland Avenue, Apartment 805, Bronx, New York 10463 (e-mail, [email protected]).

Figure 1. Survival curve for time to first contact with VA outpatient mental health services and hypothetical curve based on data points from other studies of aftercare following discharge from inpatient facilitiesa

a A (Groningen) and B (Victoria) from Sytema and Burgess (16) based on two weeks and four years of data; C, National Committee for Quality Assurance (17) based on one week and one month of data; D, Boyer et al. (18); E, Rosenheck et al. (19) based on one month and six months of data; F, Olfson et al. (20) based on data for the group with no predischarge contact; G, Rabinowitz et al. (21); H, Melzer et al. (22); I, Shepherd et al. (23)

|

Table 1. Predictors of Department of Veterans Affairs outpatient mental health contacts among servicemen and -women discharged from the U.S. Armed Forces after hospitalization with major depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia

1. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S, et al: Preventing recurrent homelessness among mentally ill men: a "critical time" intervention after discharge from a shelter. American Journal of Public Health 87:256-262, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Thornicroft G, Tansella M: The Mental Health Matrix: A Manual to Improve Services. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1999Google Scholar

3. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders, 2nd Edition. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002Google Scholar

4. Hoff RA, Rosenheck R: The use of VA and non-VA mental health services by female veterans. Medical Care 36:1524-1533, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Hoff RA, Rosenheck R: Utilization of mental health services by women in a male-dominated environment: the VA experience. Psychiatric Services 48:1408-1414, 1997Link, Google Scholar

6. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Utilization of mental health services by minority veterans of the Vietnam era. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:685-691, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Wyatt RJ, Henter I, Mojtabai R, et al: Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) in psychiatrically ill US Armed Forces personnel. Psychological Medicine, in pressGoogle Scholar

8. Rosenheck R, Stolar M: Access to public mental health services: determinants of population coverage. Medical Care 36:503-512, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Maller R, Zhou X: Survival Analysis With Long-Term Survivors. Chichester, England, Wiley, 1996Google Scholar

10. Peng Y, Dear KBG: A nonparametric mixture model for cure rate estimation. Biometrics 56:237-243, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Boag JW: Maximum likelihood estimates of the proportion of patients cured by cancer therapy. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 11B:15-44, 1949Google Scholar

12. Farewell VT: The use of mixture models for the analysis of survival data with long-term survivors. Biometrics 38:1041-1046, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Schmidt P, Witte AD: Predicting criminal recidivism using "split population" survival time models. Journal of Econometrics 40:141-159, 1989Crossref, Google Scholar

14. Schmidt P, Witte AD: Predicting Recidivism Using Survival Models. New York, Springer, 1988Google Scholar

15. Green WH: LIMDEP, Version 7.0. Plainview, NY, Econometric Software, 1998Google Scholar

16. Sytema S, Burgess P: Continuity of care and readmission in two service systems: a comprehensive Victorian and Groningen case register study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 100:212-219, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. The State of Managed Care Quality:2000. Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2000Google Scholar

18. Boyer CA, McAlpine DD, Pottick KJ, et al: Identifying risk factors and key strategies in linkage to outpatient psychiatric care. American Journal of Psychiatry 157:1592-1598, 2000Link, Google Scholar

19. Rosenheck R, Greenberg G, DiLella D: Department of Veterans Affairs National Mental Health Program Performance Monitoring System: Fiscal Year 2000 Report. West Haven, Conn, Northeast Program Evaluation Center, VA Healthcare Connecticut System, 2001Google Scholar

20. Olfson M, Mechanic D, Boyer CA, et al: Linking inpatients with schizophrenia to outpatient care. Psychiatric Services 49:911-917, 1998Link, Google Scholar

21. Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, et al: Changes in insurance coverage and extent of care during the two years after first hospitalization for a psychotic disorder. Psychiatric Services 52:87-91, 2001Link, Google Scholar

22. Melzer D, Hale AS, Malik SJ, et al: Community care for patients with schizophrenia one year after hospital discharge. British Medical Journal 303:1023-1026, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Shepherd M, Watt D, Falloon I: The Natural History of Schizophrenia: A Five-Year Follow-Up Study of Outcome and Prediction in a Representative Sample of Schizophrenia. Cambridge, England, Cambridge University Press, 1989Google Scholar

24. Rosenheck R, Massari L: Wartime military service and utilization of VA health care system. Military Medicine 158:223-228, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Rosenheck R, Fontana A: Do Vietnam-era veterans who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder avoid VA mental health services? Military Medicine 160:136-142, 1995Google Scholar

26. Gamache G, Rosenheck R, Tessler R: Factors predicting choice of provider among homeless veterans with mental illness. Psychiatric Services 51:1024-1028, 2000Link, Google Scholar

27. Becerra RM, Greenblatt M: The mental health-seeking behavior of Hispanic veterans. Comprehensive Psychiatry 22:124-133, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Kizer KW: Reengineering the veterans healthcare system, in Advancing Federal Sector Health Care: A Model for Technology Transfer. Edited by Ramsaroop P, Ball MJ, Beaulieu D, et al. New York, Springer, 2001Google Scholar

29. Congressional Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance: Report of the Congressional Commission on Servicemembers and Veterans Transition Assistance, 1999. Available at http://veterans.house.gov/hearings/schedule106/feb99/2-23-99/eib.pdfGoogle Scholar