A Survey of Psychiatric Residency Directors on Current Priorities and Preparation for Public-Sector Care

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study assessed how resident psychiatrists are being prepared to deliver effective public-sector care. METHODS: Ten leaders in psychiatric education and practice were interviewed about which tasks they consider to be essential for effective public-sector care. The leaders identified 16 tasks. Directors of all general psychiatry residency programs in the United States were then surveyed to determine how they rate the importance of these tasks for delivery of care and how their training program prepares residents to perform each task. RESULTS: A total of 114 of 150 residency directors (76 percent) responded to the survey. Factor analysis divided 14 of the tasks into three categories characterized by the extent to which their performance requires integration of services: within the mental health system (for example, lead a multidisciplinary team), across social service systems (for example, interact with staff of supportive housing programs), and across institutions with different missions (for example, distinguish behavioral problems from underlying psychiatric disorders among prisoners). Preparation for tasks that involved integration of services across institutions was rated as least important, was least likely to be required, and was covered by less intensive teaching modalities. Tasks entailing integration within the mental health system were rated as most important, preparation was most likely to be required, and they were covered most intensively. Midway between these two categories, but significantly different from each, were tasks relying on integration across social service systems. CONCLUSIONS: Tasks that involved integrating services across institutions with different missions were consistently downplayed in training. Yet the importance of such tasks is underscored by the assessments of the psychiatric leaders who were interviewed, the high valuation placed on this type of integration by a substantial subset of training directors, and the extent of mental illness among populations who are institutionalized in nonpsychiatric settings.

How will psychiatrists be prepared to effectively address the needs of public-sector patients over the next decade? The importance of this issue is demonstrated by the high prevalence of severe mental illness among marginalized populations in public settings and high rates of job turnover, dissatisfaction, and burnout among psychiatrists who care for these populations (1,2,3,4). Yet little research has been devoted to discerning appropriate future roles for psychiatrists in public-sector care and the implications for training them.

New roles in treatment delivery will be forged in the midst of dramatic changes in the mental health services environment—including significant advances in the psychiatric knowledge base highlighted by developments in neurobiology and psychopharmacology (5,6,7), the growth of managed care (8,9,10,11,12,13), heavy reliance on nonphysician therapists (14,15), and a renewed commitment to ensuring access to evidence-based, comprehensive, and integrated services for people in need (16). Against this landscape, several factors compel special attention to preparing psychiatrists to deliver public-sector care. Some of the factors cited by leaders in psychiatric education and practice who were interviewed as a prelude to this study include the heightened need to address psychosocial and socioeconomic considerations in applying the biomedical model, effectively interact with diverse agencies and institutions, function as part of a multidisciplinary team, sort out the confounding effects of severe social problems, understand complex systems, address seemingly endless needs in a chronically underresourced environment, and attend to issues of ethnicity, culture, and minority status.

To assess the current status of training for public-sector care, we surveyed directors of all general psychiatry residency programs in the United States in the summer of 2003. The content of the survey was informed by the views of leaders in psychiatric education and practice who were interviewed in depth about which tasks they consider to be essential in preparing psychiatrists to care for patients in the public sector. In the survey, training directors were first asked to rate the importance of these tasks to delivery of effective care. Then, they were asked to detail whether and how their program prepares residents to perform each task. Approval of the university committee on activities involving human subjects was obtained for all phases of the study.

Methods

To develop the survey instrument, in-depth interviews were conducted with ten leaders in psychiatric education and practice who met four selection criteria: had a national perspective, had been involved in the field for a decade or more, were knowledgeable and concerned about public-sector care, and played significant roles in key professional organizations. Collectively, they held or had held leadership positions in the following organizations: the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training, the American Psychiatric Association, the Association for Academic Psychiatry, the American Association of Chairs of Departments of Psychiatry, the American College of Psychiatrists, the American Association of Community Psychiatrists, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Open-ended questions sought the views of leaders on future roles for psychiatrists in public-sector care and what they considered to be appropriate training for effective practice. They were asked at length about the tasks that they considered essential in caring for patients. Analysis of their responses revealed an emphasis on tasks that require successfully spanning the boundaries of complex systems. Most of these tasks could be grouped into one of two categories: coordination across social service systems (for example, incorporating psychiatric intervention into psychosocial rehabilitation and interacting with staff of supportive housing programs to care for patients) and integration across institutions with different missions (for example, determining whether or not the behavioral problems of a prisoner stem from an underlying psychiatric disorder and providing ongoing treatment in nonpsychiatric settings, such as prisons or shelters). In selecting the tasks to be assessed in the survey, care was taken to accurately reflect the leaders' emphasis on these two realms of practice.

After the survey was created, eight additional experts in psychiatric education and practice provided feedback before the survey was given to the residency directors and appropriate revisions were made—for example, ensuring the use of commonly understood terminology. Residency directors were asked to rank the priority of each task. Possible scores ranged from 1 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher priority. Directors were also asked whether each task is addressed in training at their program, whether such training is required for all residents, and what type of teaching modality is employed. Further questions asked respondents whether they believe that residents need specialized training in public-sector care, the weekly number of hours typically devoted to providing services in public-sector settings, their assessment of their program's emphasis on such training relative to the average program, and their plans for adjusting that emphasis over the next five years.

To supplement the survey, program characteristics were added from the American Medical Association's (AMA's) Freida database, including ownership of the primary teaching site (that is, nonprofit, city, county, state, Department of Veterans Affairs, or other), institutional type (that is, general hospital, psychiatric hospital, mental health facility, medical school, corporation, or other), and whether it is university based.

The population of residency directors was enumerated by collecting information from the AMA master file on their list of 182 programs in general psychiatry. Each program was called to verify the identity of the training director and to elicit contact information. Of the 182 programs, several were not included for various reasons: nine could not be contacted after several attempts, five did not have directors, ten were duplicate listings (generally they were constituents of multisite programs), and eight had incorrect addresses listed. For the remaining 150 programs, 114 directors returned completed surveys, for a response rate of 76 percent. This response was generated by sending three waves of the surveys, sending two reminder notices, and following up by telephone. Respondents and nonrespondents did not differ by selected program characteristics, including geographic location and whether they were university based.

The analysis addressed the relative priority of the tasks, whether the tasks were required in the residency program, and the manner in which they were taught. Principal components analysis with varimax rotation was conducted to examine the factor structure of responses to the tasks. Loadings in excess of .45 were used to assign items to factors. Meaningful subsets of tasks were compared with regard to differences in priority, whether or not training was required, and teaching modality (t tests, analyses of variance, and chi square analyses were employed as appropriate). Similar analyses assessed whether program characteristics influenced how the priority of the tasks was rated.

Results

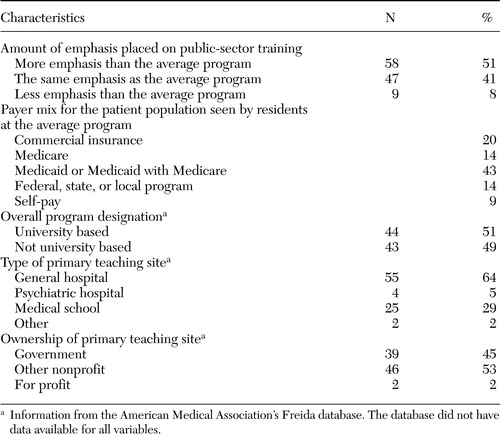

Characteristics of the residency programs are presented in Table 1. Slightly more than half of the program directors said their programs placed above average emphasis on public-sector care. On average, public financing covered the medical care for 71 percent of the patients typically seen by residents. Fifty-one percent were designated in the Freida database as university based, 69 percent had a hospital as the primary teaching site, and 45 percent were government owned.

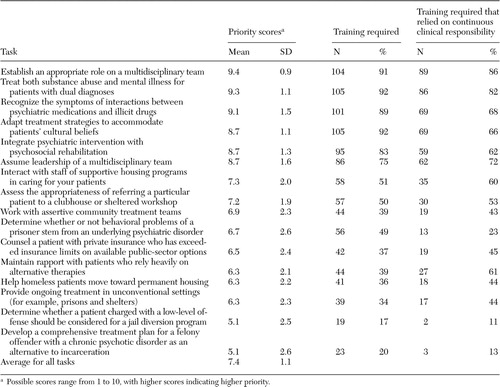

Priority ratings of the tasks essential to public-sector care are reported in Table 2. Mean ratings ranged from 5.1 to 9.4 (medium to high priority), with an overall average of 7.4. Sixty programs (53 percent) required training for at least 50 percent of the tasks.

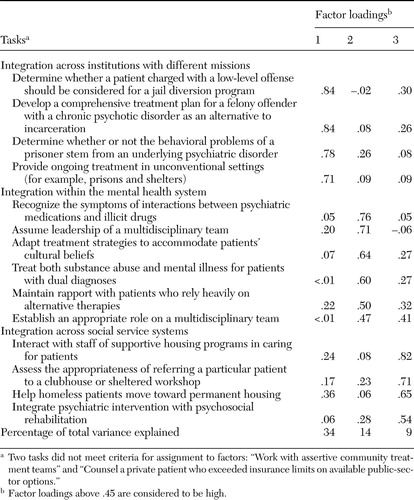

Principal components analysis of the priority ratings yielded a typology of tasks that was similar to the categorization that emerged from analysis of the interviews with leaders in psychiatric education and practice. As depicted in Table 3, the three-category characterization explained 57 percent of the variance and included 14 of 16 tasks. Conceptually, these categories describe three levels of integration of services: within the mental health system, across social service systems, and across institutions with different missions. Program directors who endorsed the view that residents need specialized training in public-sector care assigned a significantly higher priority to tasks involving integration across social service systems and across institutions with different missions, compared with directors who did not share this view (p<.05).

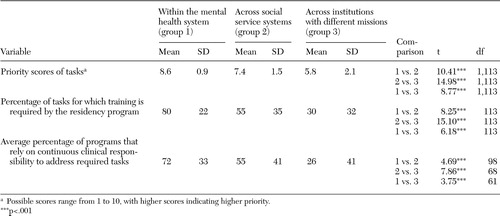

As reported in Table 4, the average priority of tasks differed significantly among the three categories; t tests were used to test significance. Top priority was assigned to tasks that entailed integration within the mental health system (mean score=8.6, p<.001), followed by those involving integration across social service systems (mean score=7.4, p<.001) and those involving integration across institutions with different missions (mean score=5.8, p<.001). The average percentage of tasks for which preparation was required by the programs also differed among these categories (Table 4). Tasks that involved integration within the mental health system were most often required (80 percent, p<.001), followed by those that involved crossing social service systems (55 percent, p<.001), and those that involved bridging disparate institutional missions (30 percent, p<.001).

Program characteristics—that is, whether the program was university based, whether the primary teaching site was a public institution, and whether the primary teaching site was a medical school, a general hospital, a psychiatric facility, or another site—did not affect how the programs rated the priority of individual tasks or of the three categories to which they belonged. Similarly, how patients paid for the services—by Medicaid, Medicare, self-pay, private, or other—did not affect the priority ratings. Furthermore, plans among training directors to increase or decrease emphasis on public-sector training were not associated with how the tasks were rated or whether they were required.

Table 2 reports the extent to which continuous clinical responsibility was the designated teaching modality to prepare residents to perform each task. (The less intensive options were didactic sessions and clinical experience with limited responsibility). The extent to which continuous clinical responsibility was required varied depending on the task, ranging from 11 to 86 percent. The relative intensity of training for the three categories of tasks was examined. Table 4 shows that the average percentage of programs that relied on continuous clinical responsibility was significantly higher for tasks entailing integration within mental health (mean=72 percent, p<.001), next highest among those involving integration across social service systems (mean=55 percent, p<.001), and considerably lower among those requiring integration across institutions with different missions (mean=26 percent, p<.001).

To assess incongruities between the priority ranking of tasks and their coverage in training, we examined—within each of the three categories—the extent to which tasks that were rated as having a higher priority than average were not addressed through training that required continuous clinical responsibility. The percentage of such items was highest in the category entailing integration across institutions with different missions (67 percent), followed by those involving integration across social service systems (34 percent) and integration within the mental health system (24 percent). The incidence of higher priority tasks not covered through intensive training was significantly greater in the interinstitutional category than in the social service systems category (t=3.27, df=48, p<.005), and, in turn, was significantly higher in the social service system category than in the mental health system category (t=3.28, df=90, p<.001).

Discussion

Although the priority ratings of tasks in public-sector care varied, the generally high valuations are indicative of an overall concordance in judgment between residency directors and the leaders in psychiatric education and practice who were interviewed for this project. Nevertheless, significant and persistent differences were found among the three categories of tasks. Tasks entailing integration of services across institutions with different missions were rated least important, preparation to perform them was least likely to be required, and, when required, the tasks were addressed through less intensive modalities. Tasks involving integration within the mental health system were rated most highly, preparation was most likely required, and they were covered through the most intensive modality—continuous clinical responsibility. Midway between these two categories, but significantly different from each, were tasks that relied on integration across social service systems. Furthermore, plans for altering the emphasis on public-sector care are not likely to affect relative priorities or how the tasks are covered in training.

Performance of tasks involving integration across institutions with different missions is central to the delivery of effective public-sector care. The importance of these tasks is underscored by the assessments of leaders in the field as well as the high valuation of these tasks by a substantial subset of training directors. Their importance is further emphasized by the extent of mental illness among populations that are institutionalized in nonpsychiatric settings. For example, estimates suggest that there are three times as many people with mental illness in jails and prisons (17) as in psychiatric institutions (18), and 40 percent of people with mental illness have had some involvement with the criminal justice system in the past five years (19). Acknowledging these dynamics, the recent report of the New Freedom Commission on Mental Health recommended the coordination of a broad array of services and attention to the interaction of mental health, employment, housing, and protection from unjust incarceration (16). Training psychiatrists to provide effective treatment in these circumstances may require special preparation for adapting therapeutic routines, addressing the effect of institutional context on patient presentation and receptivity to treatment, and negotiating challenges posed by different missions and cultures.

Some might question whether a psychiatric presence is necessary for effective care in these circumstances and advocate further reliance on nonphysician therapists (14,15,20). However, the evidence presented here supports the view that psychiatrists have an essential role in providing treatment in these interinstitutional contexts. Others may argue that general psychiatrists need not be equipped with the depth of expertise necessary for effective performance in this sphere, believing that fellowship programs—for example, those in forensic psychiatry—may train specialists to fulfill this function. However, forensic fellowships concentrate mainly on preparing psychiatrists to deliver effective testimony in the courtroom rather than equipping them to provide treatment in prisons, shelters, or other unconventional settings (21,22).

Efforts can be made to expand the number of existing training programs—residencies (23) and fellowships (2)—that specialize in preparing psychiatrists for the public sector. However, this strategy by itself is unlikely to meet the demands for care, given the prevalence of severe mental illness among marginalized populations in public-sector settings.

The current status of general residency training in this area, particularly the relative scarcity of coverage through intensive teaching modalities, may be a function of the challenges of developing high-quality educational experiences in settings with disparate missions (24,25,26). For example, in correctional institutions security concerns almost always take precedence over clinical needs (24), and an environment emphasizing coercion and control may inhibit the development of therapeutic partnerships. Clinicians and security staff, attempting to bridge such differences, often find themselves ill prepared to communicate effectively with each other (27).

Exclusivity in institutional missions is generally accompanied by segregation of financing and difficulties in blending funding streams to support training of residents and delivery of boundary-spanning services in shelters (26) and prisons (24). Politically, in effecting change, the mental health professions lack the authority over collaborating organizations that they rely on for establishing training for tasks that entail integration within the mental health system. Recognizing the myriad challenges, residency programs that value interinstitutional integration but do not offer intensive training could seek alliances with programs that have developed effective rotations in these settings with the purpose of availing their residents of these learning opportunities. The success of such strategies will depend in part on whether existing rotations have the capacity to accommodate more residents and whether programs that seek such alliances can offer training resources in return.

Conclusions

Residency programs consistently downplay preparation to perform tasks requiring integration of services across institutions with different missions, as reflected in both the frequency and intensity of the coverage of these tasks in their curriculum. Yet leaders in psychiatric education and practice believe that mastery of interinstitutional tasks is essential to delivering effective public-sector care. When high priority was assigned to these tasks among residency directors, programs did not require intensive exposure and sustained experience in addressing them. Expansion of the capacity to offer such boundary-spanning experiences in psychiatric training will likely require more attention to political, economic, and organizational barriers to developing collaborations across institutions.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by grant P50-51359 from the National Institute of Mental Health to the Center for the Study of Issues in Public Mental Health. The authors thank Amy Chepaitis, M.B.A., and Elizabeth A. Berg, M.S., for fielding the survey and managing data. They also thank Jules Ranz, M.D., for his thoughtful input on the questionnaire.

Dr. Yedidia and Dr. Gillespie are affiliated with the Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service at New York University, 295 Lafayette Street, 2nd Floor, New York, New York 10012 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Bernstein is with the department of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine in New York.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of the 114 residency programs surveyed about training for publicsector care

|

Table 2. Priority ratings of tasks central to the delivery of public-sector care among directors of 114 psychiatric residency programs and preparation for such tasks

|

Table 3. Categorization by factor analysis of tasks central to the delivery of public-sector care as rated by directors of 114 psychiatric residency programs

|

Table 4. Priority ratings and coverage of tasks in residency training that are central to the delivery of public-sector care, by type of integration

1. Brown DB, Goldman CR, Thompson KS, et al: Training residents for community psychiatric practice: guidelines for curriculum development. Community Mental Health Journal 29:271–283,1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Ranz J, Rosenheck S, Deakins S: Columbia University's fellowship in public psychiatry. Psychiatric Services 47:512–516,1996Link, Google Scholar

3. Pollack DA, Cutler DL: Changing roles: psychiatry in community mental health centers, in Innovations in Mental Health. Edited by Cooper S, Lentner Y. Sarasota FL, Professional Resource Exchange, 1992Google Scholar

4. Clark GM, Vaccaro JV: Burnout among CMHC psychiatrists and the struggle to survive. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:843–847,1987Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Lieberman JA, Rush AJ: Redefining the role of psychiatry in medicine. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1388–1397,1996Link, Google Scholar

6. Sierles FS, Taylor MA: Decline of US medical student career choice of psychiatry and what to do about it. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:1416–1426,1995Link, Google Scholar

7. Pardes H: A changing psychiatry for the future. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:1383–1386,1996Link, Google Scholar

8. Bartlett J: The emergence of managed care and its impact on psychiatry. New Directions for Mental Health Services 63:25–33,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Gonzales JJ, Randel LR: Consultation-liaison psychiatry in the managed care arena. Psychiatric Clinics of North America 19:449–466,1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Stone AA: Paradigms, pre-emptions, and stages: understanding the transformation of American psychiatry by managed care. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 18:353–387,1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Miller J: Psychiatry and managed care: under analysis. Minnesota Medicine 79:10–13, 58-59,1996Medline, Google Scholar

12. Olfson M, Weissman MM, Gottlieb JB: Essential roles for psychiatry in the era of managed care. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:206–208,1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Lazarus A: A proposal for psychiatric collaboration in managed care. American Journal of Psychotherapy 48:600–609,1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Cooper RA: Where is psychiatry going and who is going there? Academic Psychiatry 27:229–234,2003Google Scholar

15. Liberman RP, Hilty DM, Drake RE, et al: Requirements for multidisciplinary teamwork in psychiatric rehabilitation. Psychiatric Services 52:1331–1342,2001Link, Google Scholar

16. New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America, Executive Summary. DHSS pub no. SMA-03-3831. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, 2003Google Scholar

17. Psychiatric Services in Jails and Prisons: A Task Force Report. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2000Google Scholar

18. State Mental Health Agency Profiling System: 2001. National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors Research Institute. Available at http://nri.rdmc.org/defprofiles.cfmGoogle Scholar

19. Hall LL, Graf AC, Fitzpatrick MJ, et al: Shattered Lives: Results of a National Survey of NAMI Members Living with Mental Illnesses and Their Families. Treatment/Recovery Information and Advocacy Data Base (TRIAD) Report, 2003Google Scholar

20. Rubin EH, Zorumski CF: Psychiatric education in an era of rapidly occurring scientific advances. Academic Medicine 78:351–354,2003Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

21. Marrocco MK, Uecker JC, Ciccone JR: Teaching forensic psychiatry to psychiatric residents. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 23:83–91,1995Medline, Google Scholar

22. Hashman K: Post-graduate training in forensic psychiatry. Medicine and Law 13:369–372,1994Medline, Google Scholar

23. Goetz R, Cutler DL, Pollack D, et al: A three-decade perspective on community and public psychiatry training in Oregon. Psychiatric Services 49:1208–1211,1998Link, Google Scholar

24. Appelbaum KL, Manning TD, Noonan JD: A university-state-corporation partnership for providing correctional mental health services. Psychiatric Services 53:188,2002Google Scholar

25. McQuistion HL, Finnerty M, Hirschowitz J, et al: Challenges for psychiatry in serving homeless people with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services 54:669–676,2003Link, Google Scholar

26. McQuistion HL, Ranz JM, Gillig PM: A Survey of American psychiatric residency programs concerning education in homelessness. Academic Psychiatry 28:116–121,2004Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Appelbaum KL, Hickey JM, Packer I: The role of correctional officers in multidisciplinary mental health care in prisons. Psychiatric Services 52:1343–1347,2001Link, Google Scholar