The Tipping Point From Private Practice to Publicly Funded Settings for Early- and Mid-Career Psychiatrists

Until the mid 1980s, surveys conducted by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) of both members and nonmembers reported that most psychiatrists identified themselves as primarily solo, office-based practitioners. A Professional Activities Survey conducted in 1982 revealed that 57.7 percent of psychiatrists (N=19,498) reported working primarily in private practice ( 1 ). By 1988 to 1989, that figure was down to 45.1 percent ( 2 ). More recent studies have shown an ongoing decrease in the time psychiatrists spend in solo office practices, with a steady increase in the time spent working in organizational settings such as hospitals and community agencies. In fact, the APA's most recent survey, the 2002 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice (NSPP), revealed that psychiatrists are now spending as much time in organizational settings as in private office practice. We decided to look at data from the past two NSPP surveys (1996 and 2002), stratifying the sample by age, to learn whether any notable shifts in practice settings occurred during this recent period.

Methods

We examined the 2002 NSPP survey data and compared them with results of an NSPP survey conducted in 1996. The 2002 NSPP survey contacted a random sample of 2,323 of the 49,000 psychiatrists in the American Medical Association's Physician Masterfile, achieving a response rate of 52 percent (N=1,203). The data were weighted to adjust for nonresponse and provide nationally representative estimates. For this report, we looked only at the subsample of APA members (1,455 sampled; response rate of 63 percent, for N=917) within the larger sample ( 3 ). The survey delineated seven work settings, five of which we characterized as organizational settings. Three of these are publicly funded settings: inpatient unit in a public hospital, outpatient clinic in a public hospital or public freestanding facility, and other (including a nursing home, correctional facility, and residential treatment center, all of which are primarily supported by public funds). Two are private organizational settings: inpatient unit in a private hospital and outpatient clinic in a private hospital or private freestanding facility. The final two were private office practice settings: solo and group office practice.

The 1996 NSPP survey ( 4 ) contacted a random sample of 1,375 of the approximately 28,000 APA members deemed to be practicing in the United States, achieving a response rate of 70.5 percent (N=970). That survey delineated 12 work settings, nine of which we characterized as organizational settings. Six of these are publicly funded settings: a public general hospital, public psychiatric hospital, public clinic or outpatient facility, nursing home, correctional facility, and other work settings. Three are private: private general hospital, private psychiatric hospital, and private clinic or outpatient facility. The final three were private office practice settings: solo office practice, group office practice, and staff or group model health maintenance organization.

There were no major differences between respondents and nonrespondents in terms of demographic or training characteristics in either the 1996 or 2002 survey. Both cohorts were predominantly male (1996 survey, 75 percent; 2002 survey, 72 percent), Caucasian (1996 survey, 75 percent; 2002 survey, 78 percent, with smaller percentages of Asian Americans, 10-11 percent; Hispanics, 4 percent; African Americans, 3 percent; and other, 5-7 percent in both surveys), and graduates of American medical schools (1996 survey, 77 percent; 2002 survey, 78 percent). Among the usual limitations in survey research, the possibility of response bias was thus at least partially alleviated.

Note that the 12 categories outlined in the 1996 survey were collapsed into seven categories when the 2002 survey was created, eliminating subcategories that represented 5 percent or less of total responses. The public and private subcategories of both general hospital and psychiatric hospital in the 1996 surveys were collapsed into one category, inpatient units, in the 2002 survey. Also, three categories in the 1996 survey (nursing homes, correctional facilities, and other work settings) were collapsed into one category, other, in the 2002 survey. Finally, one category, health maintenance organization, was dropped because it represented less than 2 percent of respondents.

Results

The 2002 NSPP survey asked respondents to indicate the percentage of hours involving direct patient care in each of the seven settings. Respondents spent 50 percent of direct patient care hours in organizational settings. Of the total direct patient care hours, 37 percent were in publicly funded settings, including 9.4 percent in inpatient units, 16.4 percent in outpatient clinics or freestanding facilities, and 11.0 percent in other settings. An additional 13 percent of direct patient care hours were in private organizational settings, including 6 percent in inpatient units and 8 percent in an outpatient clinic or freestanding facility (the subtotals do not coincide with the total because of rounding). The remaining 50 percent of direct patient care hours were reported as spent in private office practice, including 37 percent in solo and 13 percent in group practice ( 5 ).

In the 1996 NSPP survey, respondents spent 48.2 percent of direct patient care hours in organizational settings. Of these direct patient care hours, 32.1 percent were in publicly funded settings, including 5.7 percent in public general hospitals, 6.6 percent in public psychiatric hospitals, 11.7 percent in public clinics or outpatient facilities, and 8.1 percent in other settings (including nursing homes and correctional facilities). An additional 16.1 percent of direct patient care hours were in private organizational settings, including 7.0 percent in private general hospitals, 4.7 percent in private psychiatric hospitals, and 4.4 percent in private clinics or outpatient facilities. The remaining 51.8 percent of direct patient care hours were reported as spent in private office practice, including 40.5 percent in solo and 11.3 percent in group practice.

In both 1996 and 2002 psychiatrists divided their time equally between organizational and private practice settings, spending 50 percent of their direct patient care hours in each type of setting. However, the percentage of direct patient care hours in publicly funded settings increased from 32 to 37 percent between 1996 and 2002.

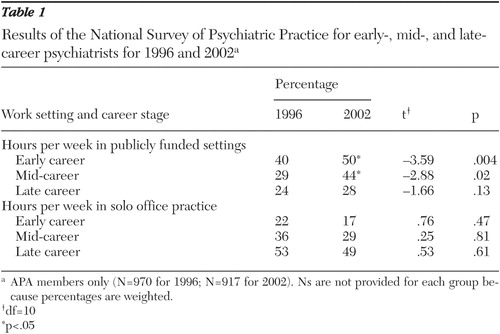

Table 1 shows the results of both the 1996 and 2002 NSPP surveys by stage of career ( 1 , 6 ). The results show that early- and mid-career psychiatrists spent significantly more time in publicly funded settings in 2002 than in 1996 (early career, t=-3.59, df=10, p=.004; mid-career, t=-2.88, df=10, p=.02). In general, psychiatrists of all ages spent less time in solo office practice in 2002 than in 1996, but these differences were not significant.

|

Table 1 shows that as of 2002 early- and mid-career psychiatrists were spending more time in publicly funded settings than in solo office practice settings (50 percent versus 17 percent of direct patient care hours for early-career psychiatrists, and 44 percent versus 29 percent for mid-career psychiatrists). This difference is significant for early-career psychiatrists (z=5.37, p<.001) but not quite for mid-career psychiatrists (z=1.90, p=.058).

Discussion

A popular image is of the psychiatrist sitting in a private office and seeing individual patients. But, in fact, that image has not kept pace with the changes in practice patterns that have been tracked by the APA. Psychiatrists increasingly work in organizational settings that are heavily supported by federal and state funding mechanisms that blur the boundary between private and public settings.

In 1996 it might have been possible to argue that early-career psychiatrists spent more hours in publicly funded than private office practice settings simply because psychiatrists were taking temporary salaried positions in publicly funded organizations early in their careers while attempting to build up private practices. But the facts that both early- and mid-career psychiatrists were spending significantly more time in publicly funded organizational settings by 2002 compared with 1996, and that by 2002 both early- and mid-career psychiatrists were spending more hours in publicly funded than solo office practice settings, suggest a more enduring change.

Well-documented economic trends offer one explanation for the movement from office-based to publicly funded settings. Commercially insured patients have an increasingly difficult time finding private psychiatrists who are willing to accept the reimbursement rates set by their insurance companies. Conversely, psychiatrists may find it more palatable to work in salaried positions where their main responsibility is to see patients while the organization accepts responsibility for dealing with the insurance companies. These organizations are able to accept fees that are not economically feasible in private practice by subsidizing clinical services through various mechanisms.

In fact, as commercial insurers have reduced reimbursement rates for psychiatric services, Medicare and Medicaid patients have become relatively more profitable to hospitals. To a large extent Medicare and Medicaid patients now partially subsidize private insurance patients in organizational settings.

The traditional definition of publicly funded services "encompasses all mental health service systems that are primarily sponsored and funded by governments—federal, state, and local. Services may be provided directly by civil servants or contracted by government to either nonprofit or for-profit agencies. The essential feature is that the clientele are the responsibility of government because they do not have the means to provide for their own care" ( 7 ).

The traditional definition of privately funded services is services that are funded by commercial insurance or self-pay. Most organizational settings are now funded by both public and private funds. Overall federal funding of mental health services (primarily Medicaid, but to a lesser extent Medicare and government contracts) has increased steadily over the past 20 years. Between 1987 and 1997 the proportion of state and local mental health services funded by Medicaid increased from one-third to one-half, and this proportion is projected to increase to two-thirds by 2017 ( 8 ). This increase has funded a steady expansion of publicly funded mental health services in various public and private nonprofit organizational settings and has opened numerous opportunities for psychiatrists to work in these settings.

In organizational services supported by both public and private funds serving both public and private patients, the traditional distinction between public and private no longer makes much sense. Most funds for psychiatric services in organizational settings are provided by federal and state governments. Of $73 billion spent on mental health services in the United States in 1997, 55 percent ($40.5 billion) came from public sources ( 9 ). This situation reflects the reality of funding for general health care as well. Government funds (Medicaid, Medicare, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Indian Health) pay 45 percent of all health care costs in the United States. Including indirect government funding through tax subsidies (such as employee health insurance), the total government contribution accounts for 60 percent of all health care spending.

Nonprofit organizations, many of which receive a substantial proportion of their funds from public sources, were classified as private in the NSPP surveys. Nonetheless, a case could be made that any nonprofit organization in which public funds provide a majority of funding for psychiatric services is a publicly funded setting. Both the psychiatrists who work in nonprofit organizations funded in part by Medicaid and Medicare and the patients being served by those organizations are often unaware of the extent to which these settings are funded by public money. Consequently, the number of direct patient care hours in publicly funded settings is undoubtedly underestimated in the NSPP surveys.

This study has several other limitations. Because we are reporting only on APA members we cannot be certain that respondents are truly representative of all psychiatrists in the nation. Second, the categories of public and private were subcategorized slightly differently in 1996 and 2002. As noted, there is no reason to believe that this difference affects the totals for public and private sectors, but there is also no way to prove this lack of effect.

What is the best way to prepare psychiatrists for the changes in practice settings noted in this article? Clearly, residency programs, professional associations, and behavioral health systems should focus more attention on the skills that psychiatrists need to work effectively in organizational settings.

A second implication is that as psychiatrists work increasingly in organizational settings, their role in these settings needs to be revisited. Many psychiatrists who are working in organizational settings take the position that they just want to "do their work" and not be bothered by unnecessary administrative demands. Yet much evidence shows that psychiatrists who perform administrative duties in organizational settings experience significantly higher job satisfaction than those who perform only clinical duties ( 10 ). Experienced psychiatric administrators should consciously pursue strategies, such as in-service training and dedicated mentoring programs, to support young psychiatrists entering these organizations.

A final implication addresses gaps in psychiatric residency training. If training remains heavily geared toward the assumption that the goal is office-based practice, psychiatric residents will receive little training in systems issues that will dramatically affect their psychiatric careers. Training needs to include further emphasis on systems of care, organizational dynamics, multidisciplinary collaboration, and funding of psychiatric services. To be sure, psychiatric residents deal with these issues every day, but they rarely are included in the formal training curriculum. In fact, a recent survey assessing the extent to which psychiatric residency training programs are preparing psychiatrists for public-sector care revealed a sharp discrepancy between the priority given to the kinds of training judged necessary to perform such care and the extent to which that training is provided ( 11 ).

A strong case can be made that because residents are not being trained to understand the complexity of organizational settings, their activities in those settings are likely to be limited to the one thing they are superbly trained to do—to prescribe medication. Thus, while psychiatrists heatedly complain about being relegated to nothing more than prescription providers, it is in fact their own training (arguably more than organizational constraints such as the fiscal pressures that encourage the provision of psychotherapy by other clinicians who are less expensive than psychiatrists) that limits their ability to participate in the full range of activities that take place in organizational settings. Evidence for this contention is that psychiatrists who receive specialized training to work in organizational settings achieve considerable productivity in those settings ( 12 ).

There is reason to hope the situation with regard to psychiatric residency training will improve. As more psychiatrists are devoting careers to public and other organizational work, their presence in faculty positions will eventually tip the balance toward a higher respect for such work among psychiatric residents. In addition, the requirement of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education that residency training programs include systems-based practices as one of the six core competencies that must be addressed is an important step that will enhance this transition. Inevitably, these developments will encourage psychiatric residents to have more understanding and respect for careers in public and organizational settings.

Conclusions

Half of all psychiatrists are now practicing in organizational settings where funding is increasingly public. Early- and mid-career psychiatrists were spending significantly more time in publicly funded organizational settings in 2002 than in 1996. In fact, early- and mid-career psychiatrists now spend more time in publicly funded than in solo office practice settings. Because it extends to mid-career psychiatrists, the shift from private office practice to publicly funded settings suggests a more enduring change in the landscape of psychiatric practice.

This article is not intended to suggest any value judgment about psychiatrists who are working in publicly funded settings versus office practice. Rather, it is intended to alert the profession to important changes taking place with regard to these practice settings. Psychiatrists, as well as the associations that represent them and the programs that train them, have to be cognizant of these dramatic shifts. In order to help psychiatrists work more effectively in organizational settings, we need to better prepare psychiatric residents by teaching them the skill sets appropriate to working in these settings. Also, all psychiatrists who enter organizational settings should be offered on-the-job training and mentoring by experienced psychiatric administrators. We plan to elaborate on these proposals in a follow-up article.

Acknowledgments

This article is a product of the Committee on Mental Health Services of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry. Data analysis was conducted by Dr. Wilk, assisted by Donald S. Rae, M.A.

1. Koran LM (ed): The Nation's Psychiatrists. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

2. Dorwart RA, Chartock LR, Dial T, et al: A national study of psychiatrists' professional activity. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:1499-1505, 1992Google Scholar

3. Colenda CC, Wilk JE, West JC: The geriatric psychiatry workforce in 2002: analysis from the 2002 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 13:756-765, 2005Google Scholar

4. Zarin DA, Pincus HA, Peterson BD, et al: Characterizing psychiatry with findings from the 1996 National Survey of Psychiatric Practice. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:397-404, 1998Google Scholar

5. Wilk JE, Regier DA, West JC, et al: Current status of the psychiatry workforce in the U.S. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, San Francisco, May 17-22, 2003Google Scholar

6. Zarin DA, Peterson BD, Suarez A, et al: Practice settings and sources of patient-care income of psychiatrists in early, mid, and late career. Psychiatric Services 48:1261, 1997Google Scholar

7. Elpers JR: Public psychiatry, in Kaplan and Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 7th ed. Edited by Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000Google Scholar

8. Buck JA: Medicaid, health care financing trends, and the future of state-based public mental health services. Psychiatric Services 54:969-975, 2003Google Scholar

9. Coffey RM, Mark T, King E, et al: National Estimates of Expenditures for Mental Health and Substance Abuse Treatment, 1997. SAMHSA pub no SMA-00-3499. Rockville, Md, Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, July 2000Google Scholar

10. Ranz JM, Stueve A: The role of the psychiatrist as program medical director. Psychiatric Services 49:1203-1207, 1998Google Scholar

11. Yedidia MY, Gillespie CC, Bernstein CA: A survey of psychiatric residency directors on current priorities and preparation for public-sector care. Psychiatric Services 57:238-243, 2006Google Scholar

12. Ranz JM, Rosenheck S, Deakins S: Columbia University's fellowship in public psychiatry. Psychiatric Services 47:512-516, 1996Google Scholar