Blood-Borne Infections and Persons With Mental Illness: Risk Factors for HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Previous reports have indicated that persons with severe mental illness have an elevated risk of contracting HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C compared with the general population. This study extends earlier findings by examining the factors that are most predictive of serologic status among persons with severe mental illness. METHODS: A total of 969 persons with severe mental illness from five sites in four states were approached to take part in an assessment involving testing for blood-borne infections and a one-time standardized interview containing questions about sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases, history of sexually transmitted diseases, and health care. RESULTS: The greater the number of risk behaviors, the greater was the likelihood of infection, both for persons in more rural locations (New Hampshire and North Carolina), where the prevalence of infection was lower, and those in urban locations (Hartford, Connecticut; Bridgeport, Connecticut; and Baltimore, Maryland), where the prevalence was higher. Although no evidence was found that certain behaviors increase a person's risk of one blood-borne infection while other behaviors increase the risk of a different infection, it is conceivable that more powerful research designs would reveal some significant differences among the risks. CONCLUSIONS: Clinicians should be attentive to these risk factors so as to encourage appropriate testing, counseling, and treatment.

Research into HIV infection provides evidence of greater vulnerability among persons with severe mental illness; reported prevalence rates range from 4 percent to 22.9 percent and average 7.8 percent (1). By comparison, Steele (2) reported an HIV seroprevalence rate of .4 percent in the general U.S. population. Similarly, the rates of hepatitis B and hepatitis C are five and 11 times the estimated general population rates, respectively (3).

Several formulations of the factors that contribute to the elevated seroprevalence in this population have been presented. First, some symptoms of severe mental illness may contribute directly to an inability to safeguard against the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases or other blood-borne infections—in particular, cognitive impairment (4). Second, the sequelae of severe mental illness often contribute to socially isolated and financially unstable lifestyles (5,6).

A third interrelated factor centers on restricted geographic and social mobility. Persons with severe mental illness live disproportionately in inner-city areas, where HIV infection rates are increasing. In addition, they may reside in settings such as psychiatric facilities or jails, where they often forge social relationships with other high-risk individuals (7,8,9). Finally, financial instability and poverty are associated with increased risk through the mechanism of trading sex for food, shelter, drugs, or money (4).

In general, persons with severe mental illness display less knowledge about HIV infection and AIDS than do those who do not have severe mental illness. In a study by Grassi and associates (10), only 19.8 percent of persons with schizophrenia indicated adequate knowledge about HIV and AIDS, compared with 80.5 percent of persons without impairment. In terms of motivation to engage in protective behaviors, most persons with severe mental illness seem to believe that they are at little or no risk of contracting HIV. In one study, nearly half of persons with severe mental illness believed that they were at no risk, whereas only 9 percent considered themselves to be at high risk (11). At the same time, persons with severe mental illness have been shown to engage frequently in high-risk behaviors. In one study, nearly half (42 to 48 percent) of persons with severe mental illness reported engaging in at least one risk behavior for HIV or sexually transmitted disease (12,13). Carey and colleagues (12) found that, among men with severe mental illness, 15 percent reported two risk factors and 9 percent reported three or more; among women with severe mental illness, these rates were 37 percent and 15 percent, respectively.

Intravenous drug use appears to be a more prevalent risk factor among persons with severe mental illness than in the general population. The estimated prevalence of intravenous drug use in the general population is 1.4 percent (14), compared with estimates ranging from 4 to 7 percent for past-year use and from 5 to 35 percent for lifetime use (12) among persons with severe mental illness (12). Steiner and associates (5) reported a rate of 14 percent among persons who had used intravenous drugs in the previous ten years. Kelly and colleagues (8) reported a rate of 24 percent for lifetime use of intravenous drugs in samples of persons with severe mental illness. In addition to being a risk factor by itself, intravenous drug use appears to increase sexual risk behaviors, including having more sexual partners per year (15), exchanging sex for money or drugs (11), having sex with unfamiliar partners or high-risk partners, and not using condoms (16,17,18).

However, definitive information on the determinants of HIV risk behaviors among persons with severe mental illness is lacking because of some significant methodologic limitations in previous studies. First, many of the studies of HIV risk among persons with severe mental illness had samples of fewer than 100 (12). Another limitation involves lack of consistent definitions for high-risk behaviors (19). Some studies have categorized individuals as having a high versus a low risk on the basis of whether the person has engaged in a single, specific risk behavior (8). Other studies have based level of risk on whether a person has engaged in a given number of risk behaviors, regardless of the specific behaviors (16). Still other researchers have used risk indexes that combine risk behaviors to produce a risk score (19).

This lack of consistency is exacerbated by the use of different reporting periods in different studies. "High risk" can refer to behaviors during the previous month, the previous year, or a person's lifetime. Many of these same methodologic concerns are also present in studies of hepatitis B and hepatitis C. Furthermore, relative rates of infection with HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness can be difficult to estimate across studies.

Similarly, research aimed at earmarking clear sociodemographic and psychiatric predictors of this higher risk of HIV infection in this population has produced mixed findings. There is some evidence that diagnosis of a psychotic disorder—or at least the experience of psychotic symptoms—is related to less knowledge about AIDS (17,20) and increased reports of HIV risk behaviors, including multiple sexual partners (17,21), exchange of sex for money or gifts (21), and intravenous drug use (16). However, other researchers have not found a relationship between risk behaviors and psychiatric diagnosis (5) or psychiatric functioning as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning scale (11).

Our multisite group of investigators, using a uniform methodology, obtained blood samples and interview information from persons with severe mental illness who were living in diverse circumstances. The prevalence findings were reported previously (3).

In this study we used data from this same large and diverse sample to clarify relationships among demographic, psychiatric, psychosocial, and behavioral predictors and HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C infection status. We also examined whether HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C infection were each predicted by the same risk factors.

Methods

A total of 969 persons with severe mental illness from five sites were approached to take part in an assessment involving testing for blood-borne infections and a one-time standardized interview containing questions about sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases, history of sexually transmitted diseases, and health care. A detailed description of the sample and data collection methods can be found in the article by Rosenberg and colleagues in this issue of Psychiatric Services (22) and in an earlier report by Rosenberg and colleagues (3).

Measures

Demographic characteristics. As part of the interview, information was gathered about participants' demographic characteristics, including age, gender, race (African American, white, Hispanic, or other), marital status and number of children, residential information (current living situation and current and lifetime homelessness), and educational, employment, income, and health insurance status (no insurance, private insurance, or Medicaid).

Infection status. A detailed description of procedures for blood collection and analysis can be found in the earlier report by Rosenberg and colleagues (3). Four infection-status variables were created from the results of blood assays. The first three variables were the positive or negative status of HIV infection or AIDS, hepatitis B infection, and hepatitis C infection, separately. A fourth variable— "any of the three infections"—was created to compare persons who tested positive for at least one of the three infections with persons who tested negative for each infection. Because the rural North Carolina site did not collect information on hepatitis, study participants from that site were deemed to be positive on the variable "any of the three infections" solely on the basis of their HIV status.

Clinical characteristics. A description of measures of clinical characteristics can be found in the accompanying article by Rosenberg and colleagues (22). Diagnostic comparisons were between persons with the psychiatric diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, and other diagnoses. Comparisons were also made between participants who did and those who did not have an alcohol use disorder, a substance use disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

AIDS Risk Inventory. The AIDS Risk Inventory, a semistructured interview measuring HIV risk behaviors associated with drug use and sexual activity (23), is described in the accompanying article by Rosenberg and colleagues (22).

Results

Univariate relationships between predictive variables and serologic results by site were examined for any clear patterns and to reduce the size of the set of predictor variables. Next, to examine the consistency of these relationships across sites, we conducted meta-analyses of the t test and chi square results, again using serologic test results as the outcome variables. We then conducted factor analyses to identify clusters of variables and used these results in regression analyses, the results of which are presented below.

Univariate relationships

Univariate relationships among 38 demographic, psychiatric, psychosocial, and behavioral predictors and four infection-status outcome variables (presence of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or any one of the three infections) were examined separately for each of the five sites by using chi square and t tests. Some relationships emerged as significant in each of the five sites (for example, total overall risk behavior was significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections" in Connecticut (t=−2.28, df=147, p=.024), Maryland (t=−3.36, df=130, p=.001), the public site in North Carolina (t=−2.92, df=175, p=.004), the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) site in North Carolina (t=−6.16, df=182, p<.001), and New Hampshire (t=−3.62, df=281, p<.001). However, other relationships were significant at some sites but not others. For example, having a current substance use diagnosis was significantly related to HIV infection among study participants in Connecticut (χ2= 4.71, df=1, p=.030), Maryland (χ2= 8.13, df=1, p=.004), and the public site in North Carolina (χ2=4.61, df=1, p=.032) but not the VA site in North Carolina or in New Hampshire.

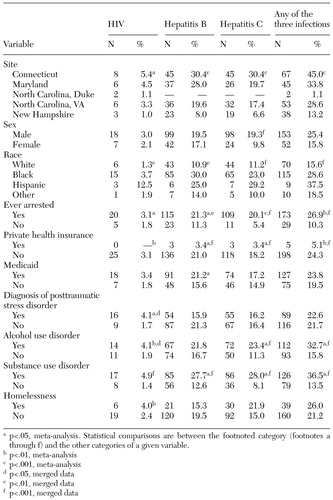

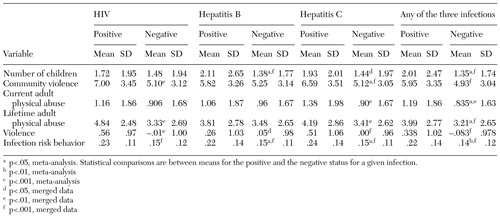

Because no clear pattern emerged across or between sites for most variables, we conducted meta-analyses of the t test and chi square results to look for stable relationships across sites. The results of these meta-analyses are presented in Tables 1 and 2, along with the results when all sites were merged and analyzed as a single sample, for comparison purposes. The categorical variables by infection status are shown in Table 1, and the continuous variables are shown in Table 2. (Possible scores on the community violence scale range from 0 to 14; on the current and lifetime adult physical abuse scales range from 0 to 9; on the violence scale (Violence Factor Score) range from 0 to 1; and on the infection risk behavior scale range from 0 to 1.)

As can be seen in Table 1, of the demographic variables, race, gender, and number of children showed some relationship to infection outcomes. Hispanic persons were most likely to test positive for at least one infection. However, race was not significantly related to any single infection. Persons who tested positive for hepatitis B and for at least one of the infections had significantly more children than those who tested negative (p=.025). The relationship between number of children and infection status approached significance (p=.070) for hepatitis C and was not significant for HIV. Finally, in terms of demographic variables, the relationship between HIV and gender approached significance (p=.053), with men more likely than women to be positive for HIV.

Across sites, participants who were HIV-positive were significantly more likely to have been homeless in the previous six months. However, homelessness was not significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections." Study participants who tested positive for at least one of the three infections were significantly less likely to have private health insurance (p=.008). This relationship was similarly significant for each of the infections separately (HIV, p= .008; hepatitis B, p=.036; hepatitis C, p=.045). Furthermore, persons who tested positive for hepatitis B (p=.035) but not for HIV or hepatitis C were more likely to have Medicaid insurance.

Persons who tested positive for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or at least one infection were more likely to have a substance use disorder (p=.039, p=.048, and p=.028, respectively). Persons with HIV, hepatitis C, or any of the infections were more likely to have an alcohol use disorder (p=.003, p=.020, and p=.041, respectively). This finding was observed across sites, except for Connecticut, where persons who tested negative for HIV were more likely to have an alcohol use disorder. Having a diagnosis of PTSD was significantly related to only one of the infection outcome measures—HIV (p=.043). Persons who were HIV-positive were more likely to have PTSD than those who were not.

Study participants who tested positive for at least one of the three infections reported more severe trauma exposure as adults, both currently (p=.048) and across their adult lifetime (p=.027). Trauma exposure was not a significant predictor of each of the three infections separately, although, for lifetime severity of trauma exposure, the relationship approached significance among persons with hepatitis C (p=.058) and HIV (p=.090). For lifetime community violence, persons who tested positive for hepatitis C reported more violence than those who tested negative (p=.048). Similarly, those who were positive for at least one of the infections, or for HIV, hepatitis B, or hepatitis C, separately, were significantly more likely to have been arrested at least once (p=.004, p=.023, p=.035, and p=.001, respectively).

Finally, as would be expected, engaging in risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases was significantly related to the variable "any of the three infections" (p=.005), hepatitis B (p=.012), and hepatitis C (p=.020)—persons who were positive for infection reported more risk behaviors. In terms of the relationship between infection risk behaviors and HIV status, site-specific differences were observed. In Maryland and in the public mental health system in North Carolina, this relationship was significant (p<.001), whereas it was not significant in Connecticut, the VA system in North Carolina, or New Hampshire.

In an attempt to reduce the number of variables used in subsequent analyses, a factor analysis was performed on lifetime community violence, current adult physical abuse, lifetime adult physical abuse, and history of arrest. One factor emerged (eignenvalue=2.209), and all four of the variables loaded onto this factor. These factor scores were then used to create a new "violence" variable, which succinctly summarized the original four variables.

Multivariate predictors across sites

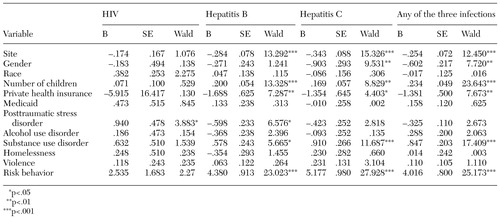

On the basis of the results of these meta-analyses, only variables that were significantly related to at least one of the three infections were used in subsequent multivariate analyses that pooled data across sites. Multiple logistic regressions were used to examine how infection status was related to gender, race, number of children, private health insurance, Medicaid insurance, homelessness, alcohol abuse diagnosis, substance abuse diagnosis, PTSD diagnosis, violence, and behavioral risk for sexually transmitted diseases.

Site was also used as a predictor to capture site-specific differences. The significant predictors of having at least one of the three infections were site, gender, number of children, private health insurance, substance use disorder, and risk behaviors for sexually transmitted diseases. As can be seen in Table 3, these variables were also significant predictors of hepatitis B and hepatitis C, except that gender was not a significant predictor of hepatitis B infection. PTSD emerged as a significant predictor of hepatitis B and the only significant predictor of HIV.

To examine the importance of predictors, we ran multiple versions of sequential regressions predicting serologic test results. The variables were entered in five steps: first, site; second, gender and race; third, number of children, risk total, PTSD, and violence; fourth, private health insurance, Medicaid, and employment; and fifth, alcohol abuse diagnosis, drug abuse diagnosis, and homelessness. The strategy for selecting the order of entry was to rank clusters of variables—with the exception of site—from the least modifiable by means of treatment interventions to the most modifiable. These regressions were then run again with site entered last rather than first. Regardless of when site was entered into the model, it was one of the strongest predictors.

Generally, few differences were found between the standard and sequential regressions, and these differences highlighted the same variables found to be important in the meta-analysis. The one difference between the two analyses was that the marginally significant relationship between race and the variable "any of the three infections" found in the meta-analysis was not significant in the regression analysis. This result suggests that the race variable was confounded with one or more of the stronger predictors, such as site. When race was examined in the regression analyses, it accounted for no significant unique effect.

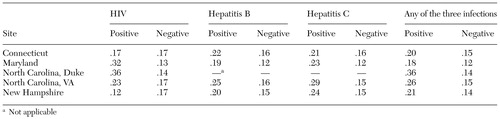

In contrast with identifying variables that could be used to predict behaviors that put an individual at greater risk of hepatitis C infection as opposed to the other infections, these analyses indicated that the sole robust predictor was the total risk variable. Greater total risk predicted a greater chance of infection with any one of the three infections, with hepatitis C alone, and with hepatitis B alone. For HIV, no significant predictors were identified, perhaps because of the low number of positive cases entered into the analyses. The relationship between the most robust predictor of infection—infection-risk behaviors—is shown by site in Table 4. (Data for hepatitis B and C from the public mental health system in North Carolina are absent from the table because information on hepatitis was not collected at that site.)

Discussion and conclusions

The rates of infection with HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C varied widely across the study sites, yet the patterns of predictors of infection were largely consistent across sites. Namely, the greater the number of risk behaviors, the greater the likelihood of infection. This observation held regardless of whether a person lived in lower-prevalence, more rural locations (from where the samples in New Hampshire and the public mental health system in North Carolina were drawn) or in higher-prevalence, urban locations (Connecticut and Maryland). The take-home lesson for persons with severe mental disorders—and the clinicians working with them—is that engaging in certain behaviors increases one's risk of infection regardless of local infection rates. Although we did not find evidence that certain behaviors put a person at a greater risk of one infection while other behaviors put the person at a greater risk of a different infection, it is conceivable that some significant differences among the risks—whether clinically important or not—may be found with more powerful research designs. Nevertheless, the message from our analysis is straightforward and uncomplicated: The likelihood of being seropositive for any one of the infections increased with a greater number of risk behaviors.

As noted in the earlier report by Rosenberg and colleagues (3), persons with severe mental illnesses have an elevated risk of each of the infections examined in this study. The results reported here extend previous findings by identifying factors that are most predictive of serologic status among these same individuals. Such risk factors for these sexually transmitted diseases include geographic location, gender, and substance abuse in addition to behavioral risk factors, such as having multiple sexual partners and sharing needles. Additional studies reported in this issue of Psychiatric Services elaborate on the interrelationships among some of these risk factors and serological status. The core finding is that clinicians should be attentive to these risk factors so as to encourage appropriate testing, counseling, and treatment.

Dr. Essock is affiliated with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Box 1230, One Gustave L. Levy Place, New York, New York 10029-6574 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Dowden is affiliated with Harvard Medical School and McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. Dr. Constantine is with the department of pathology at the University of Maryland in Baltimore. Dr. Katz is with the department of psychology of the University of Connecticut in Storrs and with Haskins Laboratories in New Haven, Connecticut. Dr. Swartz is with the department of psychiatry and behavioral science at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Osher is with the center for behavioral health, justice, and public policy at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Rosenberg is with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center of Dartmouth Medical School in Lebanon, New Hampshire. This article is part of a special section on blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness.

|

Table 1. Categorical variables in the Five-Site Health and Risk Study, by infection status

|

Table 2. Continuous variables in the Five-Site Health and Risk Study, by infection status

|

Table 3. Multivariate predictors of infection status in the Five-Site Health and Risk Study

|

Table 4. Level of risk behaviors associated with infection status by study site

1. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:259-269, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Steele FR: A moving target: CDC still trying to estimate HIV-1 prevalence. Journal of NIH Research 6:25-26, 1994Google Scholar

3. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31-37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Carmen E, Brady SM: AIDS risk and prevention for the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:652-657, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

5. Steiner J, Lussier R, Rosenblatt W: Knowledge about and risk factors for AIDS in a day hospital population. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:734-735, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

6. Stewart DL, Zuckerman CJ, Ingle JM: HIV seroprevalence in a chronically mentally ill population. Journal of the National Medical Association 86:519-523, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cates JA, Graham LL: HIV and serious mental illness: reducing the risk. Community Mental Health Journal 29:35-47, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Kelly JA, Murphy DA, Sikkema KJ, et al: Predictors of high and low levels of HIV risk behavior among adults with chronic mental illness. Psychiatric Services 46:813-818, 1995Link, Google Scholar

9. Rector NA, Seeman MV: Schizophrenia and AIDS. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:181-182, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

10. Grassi L, Pavanati M, Cardelli R, et al: HIV-risk behavior and knowledge about HIV/ AIDS among patients with schizophrenia. Psychological Medicine 29:171-179, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, et al: Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:221-227, 1994Link, Google Scholar

12. Carey MP, Carey KB, Weinhardt LS, et al: Behavioral risk for HIV infection among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness: patterns and psychological antecedents. Community Mental Health Journal 33:133-142, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Sacks M, Dermatis H, Looser-Ott S, et al: Seroprevalence of HIV and risk factors for AIDS in psychiatric inpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:736-737, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

14. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1995Google Scholar

15. Zafrani M, McLaughlin DG: Knowledge about AIDS. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 41:1261, 1990Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Carey MP, Carey KB, Kalichman SC: Risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clinical Psychology Review 17:271-291, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. McKinnon K, Cournos F, Sugden R, et al: The relative contributions of psychiatric symptoms and AIDS knowledge to HIV risk behaviors among people with severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57:506-513, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Silberstein C, Galanter M, Marmon M, et al: HIV-1 among inner city dually diagnosed inpatients. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 20:101-113, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Carey KB: Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk among the seriously mentally ill. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 3:130-143, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

20. McDermott BE, Sautter FJ, Winstead DK, et al: Diagnosis, health beliefs, and risk of HIV infection in psychiatric patients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:580-585, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

21. Miller LJ, Finnerty M: Sexuality, pregnancy, and childrearing among women with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders. Psychiatric Services 47:502-506, 1996Link, Google Scholar

22. Rosenberg SD, Swanson JW, Wolford GL, et al: The Five-Site Health and Risk Study of Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 54:827-835, 2003Link, Google Scholar

23. Chawarski MC, Plakes J, Schottenfeld RS: Assessment of HIV risk. Journal of Addiction Disorders 17:49-59, 1998Google Scholar