Blood-Borne Infections and Persons With Mental Illness: The Five-Site Health and Risk Study of Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness

Abstract

This article outlines the history and rationale of a multisite study of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness reported in this special section of Psychiatric Services. The general problem of blood-borne diseases in the United States is reviewed, particularly as it affects people with severe mental illness and those with comorbid substance use disorders. The epidemiology and natural history of three of the most important infections are reviewed: the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the hepatitis B virus, and the hepatitis C virus. Current knowledge about blood-borne diseases among people with severe mental illness as well as information on current treatment advances for hepatitis C are summarized. A heuristic model, based on the pragmatic, empirical, and conceptual issues that influenced the final study design, is presented. The specific rationale of the five-site collaborative design is discussed, as well as the sampling frames, measures, and procedures used at the participating sites. Alternative strategies for analyzing data deriving from multisite studies that use nonrandomized designs are described and compared. Finally, each of the articles in this special section is briefly outlined, with reference to the overall hypotheses of the studies.

The problem of blood-borne and sexually transmitted diseases, particularly the worldwide AIDS pandemic, has become a focus of increased public health concern over the past two decades. More than 40 million people, most of them living in the developing world, are now infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (1). AIDS was first identified in the United States in 1981 and was initially thought to be an immune deficiency disorder affecting gay men. The underlying pathogenic agent, HIV, was not identified until 1984 as a human retrovirus. In the United States, an estimated 420,000 people have died from AIDS, and an estimated 900,000 people are currently infected with HIV (2).

Far less public attention has been focused on the problem of infectious hepatitis, even though approximately 1.25 million Americans are now infected with the hepatitis B virus and 3.9 million (almost 300 million people worldwide) with hepatitis C (3,4). Eight to ten thousand deaths in the United States are anticipated this year as a result of liver disease related to chronic hepatitis C infection, and that number is expected to triple in the next two decades (4,5). The costs in terms of medical treatments, including liver transplants, are likely to be staggering.

One reason for the relative lack of attention to hepatitis C is that the virus was identified only as recently as 1988 (6). Moreover, hepatitis C is a silent disease, with symptoms developing an average of 20 years after infection in approximately 20 percent of chronically infected persons. Unfortunately, by the time symptoms of infection appear, liver damage has already occurred.

The first published report that people with severe mental illness have an elevated risk of HIV infection appeared in 1989, and this finding has since been replicated in numerous studies (7,8,9,10,11,12,13). In addition, people who have both a psychotic disorder and HIV infection are more likely to delay treatment and to engage in behavior that worsens the course of the infection, leading to a 50 percent increase in mortality. People with severe mental illness appear to have a higher risk of HIV for a variety of reasons, including elevated rates of injection drug use; multiple, high-risk sexual partners; infrequent use of condoms; a tendency to trade sex for material gain; and engagement in sexual activity while using psychoactive substances (14,15,16,17). These behaviors also suggest elevated risk of hepatitis B and C, of which the estimated prevalence in the U.S. population is 4.9 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively. Elevated rates of infectious hepatitis among psychiatric patients in other countries have been reported (18,19), but there is a dearth of published information on the problem of hepatitis B or C among people with severe mental illness in the United States.

Background

Findings from the Five-Site Health and Risk Study confirm that the risk of HIV infection is markedly elevated among persons with severe mental illness (11). The HIV prevalence of 3.1 percent was approximately nine times the overall rate for the United States, although far below the mean estimate of approximately 8 percent derived from earlier studies of this population (9). The most surprising finding was that the prevalence of hepatitis C was 19.6 percent, or approximately 11 times the overall population rate. The prevalence of hepatitis C infection in metropolitan areas was 25.4 percent and in nonmetropolitan areas 10.6 percent. Approximately 30 percent of the 931 clients assessed had hepatitis, HIV, or both, and approximately half of those with a dual diagnosis (severe mental illness plus a substance use disorder) were seropositive.

Among clients who acknowledged injecting drugs even once during their lifetimes, close to two-thirds tested positive for hepatitis C. Although people who are chronically infected with the hepatitis C virus are typically asymptomatic, they continue to be infectious to others through various—primarily blood-borne—routes of contact. Newer drugs, such as pegylated interferon, have become available for treatment of hepatitis C and appear to be effective in eradicating the virus. It is important to test for infection early so that antiviral treatment can be administered, if indicated, before significant liver damage occurs and so that other important medical and behavioral interventions can be implemented.

The Five-Site Health and Risk Study of Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness

The larger study that provided data for this study was designed and conducted by the Five-Site Health and Risk Study Research Committee: Susan M. Essock, Ph.D., Jerilynn Lamb-Pagone, M.S.N., A.P.R.N. (Connecticut); Marvin Swartz, M.D., Jeffrey Swanson, Ph.D., Barbara J. Burns, Ph.D. (North Carolina, Duke); Marian I. Butterfield, M.D., M.P.H., Keith G. Meador, M.D., M.P.H., Hayden B. Bosworth, Ph.D., Mary E. Becker, Richard Frothingham, M.D., Ronnie D. Horner, Ph.D., Lauren M. McIntyre, Ph.D., Patricia M. Spivey, Karen M. Stechuchak, M.S. (North Carolina, Durham); Fred C. Osher, M.D., Lisa A. Goodman, Ph.D., Lisa J. Miller, Jean S. Gearon, Ph.D., Richard W. Goldberg, Ph.D., John D. Herron, L.C.S.W.-C., Raymond S. Hoffman, M.D., Corina L. Riismandel, B.A. (Maryland); Stanley D. Rosenberg, Ph.D., George L. Wolford, Ph.D., Patricia C. Carty, M.S., Robert E. Drake, M.D., Ph.D., Kim Mueser, Ph.D., Mark C. Iber, B.A., Ravindra Luckoor, M.D., Gemma R. Skillman, Ph.D., Rosemarie S. Wolfe, M.S., Robert M. Vidaver, M.D., Michelle P. Salyers, Ph.D. (New Hampshire).

Epidemiology, natural history, and routes of transmission

HIV

Despite significant recent advances in treatment, HIV infection and AIDS constitute an incurable disease that is a major cause of death in the United States.

Worldwide, the predominant route of transmission of HIV has been and remains heterosexual sex. In the United States, however, the initial epidemic was primarily among men having sex with men. Intravenous and intranasal drug use now represent the predominant route of HIV transmission in many areas of the United States and the leading route of transmission to women. Finally, the proportion of newly diagnosed cases among women compared with men is steadily growing, as is the proportion of new cases among persons from racial and ethnic minorities.

The natural history of HIV is inexorable destruction of the immune system and eventual death from AIDS, but the rate of progression of HIV is highly variable.

Hepatitis B

Between 5 percent and 20 percent of the U.S. population have been infected with the hepatitis B virus. Following exposure, most people clear the virus. However, an estimated .4 percent of the population are chronically infected. A majority of infected infants—but less than 10 percent of infected adults—develop chronic disease. Two major complications of chronic hepatitis B infection are cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, but only a minority of patients develop these complications. Hepatitis B is readily transmitted through blood and other body fluids. In contrast with HIV and hepatitis C, hepatitis B can persist on environmental surfaces for prolonged periods, which can lead to infection through some forms of casual contact, and is now a vaccine-preventable disease. Thus all at-risk individuals should receive the hepatitis B vaccine.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C is the most common chronic blood-borne infection in the United States, with an estimated national prevalence of 1.8 percent. Hepatitis C is transmitted through the same routes as is HIV, but the relative efficiency of transmission differs. Transmission through contaminated blood, either through blood products or drug paraphernalia, is the most efficient route of transmission—even more efficient than for HIV. This efficiency of transmission results in a prevalence of hepatitis C infection of 79 percent among intravenous and intranasal drug users and accounts for approximately 60 percent of all cases of hepatitis C infection in the United States.

Sexual transmission of hepatitis C is far less efficient than that of HIV, and the estimated risk of vertical transmission (mother to infant) is 5 percent. The natural history of hepatitis C is highly variable. Approximately 85 percent of persons infected with hepatitis C develop lifelong chronic infection. Approximately 20 percent of chronically infected persons will develop cirrhosis, and approximately 3 percent will develop hepatocellular carcinoma. The risk of progression to an end-stage complication of hepatitis C infection is affected by characteristics of both the virus and the host, including alcohol use and concomitant immunosuppression, including that associated with AIDS.

Treatment of hepatitis C infection includes several modalities (3). Important behavioral interventions include the elimination of alcohol use; the avoidance of other hepatotoxins, including certain foods and medications; and modification of behaviors associated with a risk of transmission. All nonimmune persons should receive immunization against both hepatitis B and hepatitis A. Clients should be evaluated for concomitant liver disease and for the extent of current liver disease. Finally, the option of specific antiviral therapy should be considered (20).

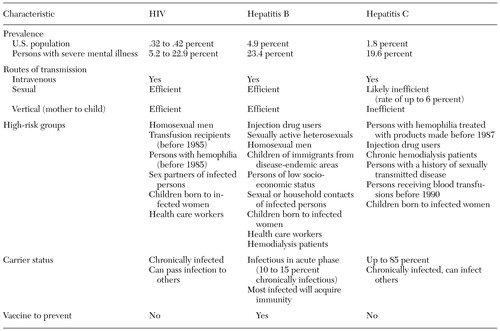

Some of the salient features of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C are summarized in Table 1.

The five-site study

Context and rationale

More than a dozen peer-reviewed research articles have reported an elevated prevalence of HIV infection among persons with severe mental illness—5.2 to 22.9 percent compared with an estimated prevalence of .32 percent to .42 percent in the U.S. adult population (21,22) and .6 percent worldwide. In response to this problem, the Center for Mental Health Research on AIDS of the National Institute of Mental Health convened a national conference of experts in May 1996 to review the extant research and to design a research agenda for understanding and reducing the impact of the AIDS epidemic on this population. Recommendations stemming from the conference (23) included rapid initiation of large, multisite study designs, using common measures and diverse samples (for example, urban, suburban, and rural sites); greater attention to basic measurement concerns, including reliability and validity of self-reported risk behavior among persons with severe mental illness; investigation of the links between specific aspects of severe mental illness and risk behavior; and assessment of the contextual determinants of risk level, including gender issues, history, risk of sexual victimization, living conditions, and social supports.

In response to these recommendations, in 1997 we began a multisite study to gather information on the epidemiology of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and other blood-borne infections in relatively large, representative samples of patients with severe mental illness in Connecticut, Maryland, New Hampshire, and North Carolina. These samples were ethnically and racially diverse and included patients from large and small urban centers as well as rural areas. Estimated population rates of HIV and other blood-borne infections varied widely among the four participating states, from some of the highest to some of the lowest in the United States. Study goals included assessing the prevalence of blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness; identifying risk factors, including psychiatric, substance use, and other comorbid disorders as well as gender and specific HIV risk behaviors; determining the mental health and medical services implications of infection; and examining contextual or environmental factors hypothesized to bear on this complex set of health problems.

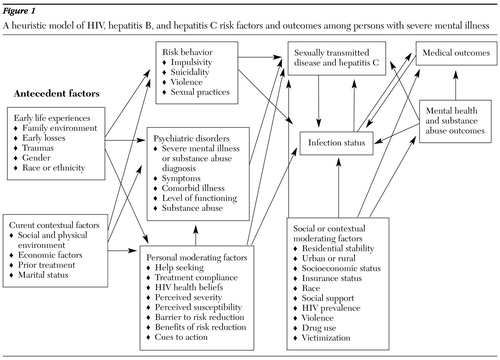

A heuristic model of relevant factors was developed and guided our selection of study variables and hypotheses. This model is presented in Figure 1. Main details of the seroprevalence aspect of the study have been reported previously (11), but below we briefly summarize information on sampling and data-gathering procedures.

Study participants

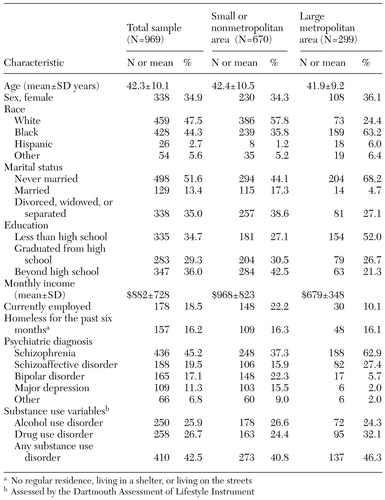

A total of 969 patients entered the study between June 1997 and December 1998. The patients were between the ages of 18 and 60 years, were fluent in English, and met common criteria for severe mental illness, including diagnosis of a major mental disorder, duration of illness of at least one year, and disability in at least two life domains—for example, work and social relationships. Approximately 87 percent of the patients we approached consented to participate in the assessments. More than 93 percent had diagnoses of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder, or major depression, and more than 42 percent had a concurrent substance use disorder.

All participants were recipients of inpatient (N=326) or outpatient (N= 643) treatment through the public mental health systems of Connecticut, Maryland, New Hampshire, or North Carolina or the Durham, North Carolina, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VA). The inpatients were consenting patients who were consecutively admitted during the study period to the New Hampshire Hospital or the Durham VA inpatient psychiatric unit. Outpatients were chosen in one of two ways: selected randomly from the rolls of three community mental health centers serving as study sites in New Hampshire and in Baltimore (N=293) or selected through participation in ongoing studies of mental health treatment in community settings. The latter group had previously been selected to participate in studies of dual diagnosis treatment in Bridgeport and Hartford, Connecticut (N=158) or outpatient commitment after discharge from involuntary hospitalization in North Carolina (N=192). The clients from Baltimore all met DSM-IV criteria for a schizophrenia-spectrum disorder.

The Connecticut and Maryland samples were drawn from large metropolitan areas known to have high prevalence rates of HIV infection or AIDS and hepatitis C infection. The New Hampshire and North Carolina samples, drawn from rural and small metropolitan areas, had much lower estimated population rates of these infections. In North Carolina, the study participants were residents of the Piedmont area, where the population is primarily African American. The New Hampshire sample was more than 95 percent Caucasian, which is consistent with the racial composition of that state.

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics for the total sample are summarized in Table 2. The sample is representative of patients being treated by public-sector psychiatric care providers in these four states but overrepresents African Americans and males and underrepresents Hispanic persons. Other characteristics—for example, psychiatric diagnoses, prevalence of substance use disorders, age, socioeconomic status, and marital status—are typical of samples with severe mental illness.

The analyses reported by Essock and colleagues (24) in this special section used data from all 969 participants in the five-site study. However, as previously described (11), 192 of the study participants (primarily the North Carolina outpatient sample) were not assessed for hepatitis B and hepatitis C serostatus. Accordingly, the articles by Butterfield and associates (25) and Swartz and associates (26), which focus on the factors related to hepatitis C infection, relate to only a subset of 777 clients for whom hepatitis C serostatus could be reliably determined. Characteristics of this subsample are reported in those articles. The study by Osher and colleagues (27) began by examining the same group of 777 participants but, for purposes of primary statistical analyses, eliminated an additional 105 persons who were hepatitis C-negative but who tested positive for either HIV or hepatitis B.

Procedures

Assessments were conducted by experienced interviewers, who received additional conjoint training on legal, ethical, and clinical issues related to blood testing and pre- and posttest counseling. The participants provided informed consent and then responded to standardized interviews to ascertain sociodemographic characteristics; substance use; risk behavior for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C; history of infectious diseases; health care; and other illness-related variables. The participants also received pretest counseling for HIV infection or AIDS and provided blood specimens either through venipuncture (N=754) or finger stick (N=177). Details of laboratory blood analyses have been published previously (11). All participants were paid a participation fee of $35 and were provided with test results and posttest counseling. All patients with positive serology screens were referred for follow-up testing and treatment with appropriate providers. These procedures, along with the informed consent forms, were approved by the participating institutions' institutional review boards.

Measures

Background characteristics assessed included sex, age, race, marital status, poverty level, employment status, recent homelessness, and diagnosis. We defined homelessness as having no regular residence or living in a shelter or on the streets at some point during the previous six months. Poverty status was determined on the basis of the 1999 poverty guidelines of the Department of Health and Human Services (28).

Most psychiatric diagnoses (782, or 80.7 percent) were obtained from chart review and available clinical data, and 187 (19.3 percent) were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (29). Four of the sites assessed the validity of chart diagnoses by administering the Structured Clinical Interview and found high concordance rates. Current alcohol and drug use disorders were identified with the Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (30), an 18-item screening tool for substance abuse or dependence specifically developed and validated for patients with severe mental illness. The scale has high classification accuracy for current abuse of alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine in this patient population.

To assess risk behaviors associated with HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C, we used the AIDS Risk Inventory, a structured interview for assessing risk behaviors associated with acquiring and transmitting these infections (31,32). This scale measures risky sexual practices; risky drug practices, such as needle sharing; and knowledge and attitudes about HIV. The scale was modified for this study to be easily understood by respondents with severe mental illness.

Clinical, health, and service use variables were assessed in several ways. The Short Form-12 Health Survey (SF-12) (33,34) was used to assess two components of health-related quality of life: the mental component summary score and the physical component summary score. The SF-12 is reliable and valid among persons with severe mental illness (35).

Other health and service use variables were obtained from the Piedmont Health Survey used in the Epidemiological Catchment Area study as adapted for this study (36). Clinical and physical health indexes included recent psychiatric and medical hospitalizations; age of first psychiatric hospitalization; chronic health problems; treatment for physical health problems; and number of days hospitalized for physical health problems. Participants were asked whether they had ever had a diagnosis of asthma, diabetes, heart trouble, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, lung disease, ulcer, stroke, epilepsy, head injury, or infectious disease—for example, chlamydia.

Childhood assault. We used the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire (37,38) to assess sexual assault before the age of 16 years. This scale has been shown to have good test-retest reliability among persons with severe mental illness (39).

To assess child physical assault, we combined several items from the violence subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scales (40,41), which is a widely used measure of domestic violence (42). We defined child physical assault as any form of beating, choking, kicking, burning, or use of a weapon by a parent or another caregiver before the participant had reached the age of 16 years.

Adult and recent assault. Assault during adulthood and over the previous year were assessed with the physical assault and sexual assault subscales of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (43). Adult physical assault included acts ranging from grabbing, pushing, or shoving to use of a knife or a gun. We defined adult sexual assault as forced or threatened oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was assessed with the PTSD Checklist (44), a self-report screening measure that includes 17 questions, one for each DSM-IV PTSD symptom. Respondents rate the severity of each symptom over the previous month on a 5-point Likert scale. This scale has strong test-retest reliability and internal consistency among persons with severe mental illness (35,45), and scale scores are moderately to strongly related to PTSD diagnoses based on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (45,46,47).

Reliability of measures

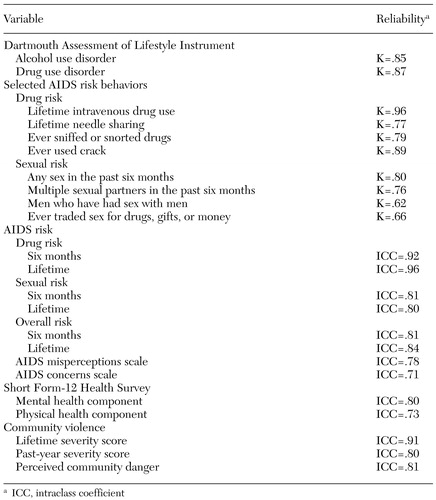

The length of the overall assessment made it clinically and ethically unacceptable to undertake test-retest reliability procedures for the entire interview. We thus chose selected scales, with particular emphasis on proximal risk and health variables, for study-specific psychometric evaluation. Seventy-seven patients were retested, approximately one week later, on substance use disorder, HIV risk behavior and knowledge, health status and exposure to violent victimization, and perceived dangerousness of the environment. Intraclass correlations for all scales were in the good-to-excellent range, as can be seen from Table 3.

We also assessed interrater reliability for these same scales, with interviewers from all participating sites independently rating videotaped interviews from each site. Interclass correlations were excellent, ranging from .90 (severity of community violence) to 1 (HIV risk).

Statistical analyses in multisite studies

Multisite epidemiologic studies offer a number of advantages, including the size and diversity of the sample, greater generalizability of findings, and replication of findings in various environments. Greater statistical power, in turn, allows more precise and robust estimation of incidence, prevalence, multivariate risk associations, etiological pathways, and contextual, subgroup, and interaction effects. At the same time, multisite studies create complexities in the analysis and interpretation of data. If large average differences are found between the sites in sociodemographic and environmental characteristics, base rates of disease, risk exposures, and risk-effect sizes, it may be difficult to pool data or draw meaningful comparisons.

Site differences can lead to two problems: erroneous conclusions about relationships between variables and misleading point estimates about prevalence. An example of the former might be the relationship between gender and infection. If study sites have different base rates of infection and low-prevalence sites have a higher proportion of women participants, the association of gender with infection rate could be confounded by site. Statisticians have referred to this statistical artifact as Simpson's paradox (48). An example of the second problem (distorted point estimates) is illustrated by the overrepresentation of rural areas and underrepresentation of urban areas in the five-site sample compared with current U.S. census data. A point estimate of prevalence based on the collapsed data set that paid no attention to the problem would yield an inaccurate value for the population as a whole.

A number of specific techniques have been developed to address the problems encountered in comparing, combining, and synthesizing evidence from different studies or cluster-sampled studies with common designs (49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58). These methods include pooling samples after weighting cases to known population distributions, using robust variance estimation to adjust for sample clustering and weighting, and using staged regression analyses with site proxies and site-by-covariate interactions.

In the studies reported in this special section, we incorporated several techniques for addressing these issues, depending on the particular research questions that each analysis addressed, the methodologic issues that each had to confront, and the distribution of relevant variables. As a general strategy, we first examined distributions and relationships within the individual sites, then made comparisons across sites—noting consistencies and differences—and, finally, pooled the site data with appropriate adjustments to develop common estimates and models whenever possible.

Three basic approaches were used to analyze combined site data. First, Essock and colleagues (24) and Osher and colleagues (27) controlled for site-specific effects directly by entering dummy variables for site in staged multivariate regression models. A second approach to combining site data was used by Swartz and colleagues (26), who developed sample weights to adjust for site differences on key variables associated with hepatitis C risk status. Each of the samples was weighted to match distributions on age and substance abuse comorbidity that were derived from a nationally representative probability sample of the U.S. population of treated persons with severe mental illness. To control for design effects (sample weighting and variance clustering by site), logistic regression models were estimated by using robust variance adjustments. The third approach, used by Butterfield and colleagues (25), examined odds ratios in unweighted data within a site, tested for homogeneity of odds ratios across sites, and, where appropriate, combined odds ratios across sites to test overall hypotheses. These researchers also fit an overall model by using multilevel generalized estimating equations, treating site as a random effect (25,59).

The sequence of articles in this special section follows the logic of the heuristic model depicted in Figure 1 and reflects the important policy and treatment issues that emerge from study findings. The article by Essock and colleagues (24), "Risk Factors for HIV, Hepatitis B, and Hepatitis C Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness," provides a general test of the model and identifies the most salient risk factors for infection in the population with severe mental illness. "Substance Abuse and the Transmission of Hepatitis C Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness," by Osher and colleagues (27), focuses more explicitly on patterns of substance abuse in this population and examines the relationships between specific drug-related behaviors and hepatitis C infection.

Butterfield and colleagues (25) look at gender differences in hepatitis C and risks among persons with severe mental illness and examine both prevalence issues related to gender and differences in actual risk behaviors among men and women with severe mental illness. Proceeding from these epidemiologic findings, Swartz and colleagues (26) examined the issue of regular sources of medical care among persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis infection and found that many infected persons had no regular source of medical care—much less access to the level of monitoring and care necessitated by their disease. In the final article, "Responding to Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness," Brunette and colleagues (20) summarize the findings of the five-site collaborative study, consider best-practice recommendations for hepatitis C, and discuss recommendations for developing effective service strategies in public mental health settings.

Conclusions

The field of mental health needs to recognize and respond to the growing problem of blood-borne diseases among persons with severe mental illness. The articles in this special section examine this problem from a number of clinically relevant perspectives and can contribute to future inquiry and immediate clinical response. Although our sampling strategy raises questions about the generalizability of study results, the data presented do represent a broad cross-section of clients with severe mental illness who are receiving treatment in a variety of public mental health settings. Thus it is likely that the findings reported here are more representative of that population than most previously published data on blood-borne diseases among persons with severe mental illness. The use of standardized measures and procedures and the gathering of multiple types of data—objective, self-reported, laboratory, background, illness-related, and behavioral—also represent strengths of this study. We hope that this special section will prove useful in helping the field begin to gain knowledge about some key problems identified at the National Working Conference on HIV and AIDS Among the Severely Mentally Ill.

Acknowledgments

The multisite study on which the articles in this special section are based was supported by grants R01-MH-50094-03S2, P50-MH-43703, R01-MH-48103-05, P50-MH-51410-02, R24-MH-54446-05, and R01-MH-52872 from the National Institute of Mental Health and grant EPP97-022 from the Department of Veterans Affairs Epidemiologic Information and Research Center. The authors thank Ellen L. Stover, Ph.D., Director of the National Institute of Mental Health's division of mental disorders, behavioral research, and AIDS, for her help in the planning and conceptualization of this study and in the writing of this article.

Dr. Rosenberg and Dr. Wolford are affiliated with the New Hampshire-Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center of Dartmouth Medical School, 2 Whipple Place, Suite 202, Lebanon, New Hampshire 03768 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Swanson, Dr. Swartz, and Dr. Butterfield are with the services effectiveness research program in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. Dr. Butterfield is also with the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Durham. Dr. Osher is with the Center for Behavioral Health, Justice, and Public Policy at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Essock is with the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City. Dr. Marsh is with the section of infectious disease of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. This article is part of a special section on blood-borne infections among persons with severe mental illness.

Figure 1. A heuristic model of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C risk factors and outcomes among persons with severe mental illness

|

Table 1. Salient features of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C

|

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants in the Five-Site Health and Risk Study

|

Table 3. Test-retest reliability for the Five-Site Health and Risk Study (N=77)

1. Satcher D: The global HIV/AIDS epidemic. JAMA 281:1479, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Surveillance Report. Atlanta, Ga, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1999Google Scholar

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Recommendations for prevention and control of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV-related chronic disease. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 47(RR19):1-39, 1998Google Scholar

4. Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, et al: The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. New England Journal of Medicine 341:556-562, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. El-Serag HB, Mason AC: Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 340:745-750, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, et al: Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science 244:359-362, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Cournos F, Empfield M, Horwath E, et al: The management of HIV infection in state psychiatric hospitals. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:53-57, 1989Google Scholar

8. Carey MP, Weinhardt LS, Carey KB: Prevalence of infection with HIV among the seriously mentally ill: review of the research and implications for practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 26:262-268, 1995Crossref, Google Scholar

9. Cournos F, McKinnon K: HIV seroprevalence among people with severe mental illness in the United States: a critical review. Clinical Psychology Review 17:159-169, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Kalichman SC, Carey MP, Johnson BT: Prevention of sexually transmitted HIV infection: a meta-analytic review of the behavioral outcome literature. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 18:6-15, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, et al: Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 91:31-37, 2001Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Silberstein C, Galanter M, Marmon M, et al: HIV-1 among inner city dually diagnosed inpatients. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 20:101-113, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Susser E, Valencia E, Conover S: Prevalence of HIV infection among psychiatric patients in a New York City men's shelter. American Journal of Public Health 83:568-570, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Boschert S: Psychosis and HIV are a lethal combination: depression, anxiety don't affect survival. Clinical Psychiatry News, Feb 1998, p 21Google Scholar

15. Carey MP, Carey KB, Kalichman SC: Risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among persons with severe mental illnesses. Clinical Psychology Review 17:271-291, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, et al: Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 151:221-227, 1994Link, Google Scholar

17. McKinnon K: Sexual and drug risk behavior, in AIDS and People With Severe Mental Illness: A Handbook for Mental Health Professionals. Edited by Cournos F, Balakar N. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1996Google Scholar

18. Chang TT, Lin H, Yen YS, et al: Hepatitis B and hepatitis C among institutionalized psychiatric patients in Taiwan. Journal of Medical Virology 40:170-173, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Di Nardo V, Petrosillo N, Ippolito G, et al: Prevalence and incidence of hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and human immunodeficiency virus among personnel and patients of a psychiatric hospital. European Journal of Epidemiology 11:239-242, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Brunette MF, Drake RE, Marsh BJ, et al: Responding to Blood-Borne Infections Among Persons With Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatric Services 54:860-865, 2003Link, Google Scholar

21. McKinnon K, Cournos F: HIV infection linked to substance use among hospitalized patients with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 49:1269, 1998Link, Google Scholar

22. McQuillan GM, Khare M, Karon JM, et al: Update on the seroepidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus in the United States household population: NHANES III, 1988-1994. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Human Retrovirology 14:355-360, 1997Crossref, Google Scholar

23. McKinnon K, Carey MP, Cournos F: Research on HIV, AIDS, and severe mental illness: recommendations from the NIMH National Conference. Clinical Psychology Review l17:327-331, 1997Google Scholar

24. Essock SM, Dowden, S, Constantine NT, et al: Risk factors for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:836-841, 2003Link, Google Scholar

25. Butterfield MI, Bosworth HB, Meador KG, et al: Gender differences in hepatitis C infection and risks among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:848-853, 2003Link, Google Scholar

26. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ, et al: Regular sources of medical care among persons with severe mental illness at risk of hepatitis C infection. Psychiatric Services 54:854-859, 2003Link, Google Scholar

27. Osher FW, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, et al: Substance abuse and the transmission of hepatitis C among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services 54:842-847, 2003Link, Google Scholar

28. US Department of Health and Human Services: Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. Federal Register 64:13428-13430, 1999Google Scholar

29. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I and II DSM-IV Disorders: Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department, 1996Google Scholar

30. Rosenberg SD, Drake, RE, Wolford GL, et al: The Dartmouth Assessment of Lifestyle Instrument (DALI): a substance use disorder screen for people with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:232-238, 1998Abstract, Google Scholar

31. Chawarski MC, Baird JC: Comparison of two instruments for assessing HIV risk in drug abusers, in Social and Behavioural Science: Proceedings of the 12th World AIDS Conference, 1998, Jun 28-Jul 10, Geneva, 1998Google Scholar

32. Chawarski MC, Pakes J, Schottenfeld RS: Assessment of HIV risk. Journal of Addictive Diseases 17:49-59, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220-233, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Ware JE, Kemp JP, Buchner DA, et al: The responsiveness of disease-specific and generic health measures to changes in the severity of asthma among adults. Quality of Life Research 7:235-244, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

35. Salyers MP, Bosworth HB, Swanson JW, et al: Reliability and validity of the SF-12 Health Survey among people with severe mental illness. Medical Care 38:1141-1150, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al: Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. JAMA 264:2511-2518, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Rodriguez N, Ryan SW, Vande Kemp H, et al: Posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse: a comparison study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:53-59, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Ryan SW: Psychometric analysis of the Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire. Dissertation Abstracts International 1991:2268, 1992Google Scholar

39. Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, et al: Reliability of reports of violent victimization and PTSD among men and women with SMI. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:587-599, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Straus MA: The Conflict Tactics Scales and its critics: an evaluation and new data on validity and reliability, in Physical Violence in American Families. Edited by Straus MA, Gelles RJ. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction, 1990Google Scholar

41. Straus MA: Injury and frequency of assault in the "representative sample fallacy" in measuring wife beating and child abuse, in Physical Violence in American Families. Edited by Straus MA, Gelles RJ. New Brunswick, NJ, Transaction, 1990Google Scholar

42. Straus MA: Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict (CT) Scales, in Physical Violence in American Families, ibidGoogle Scholar

43. Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, et al: The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues 17:283-316, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

44. Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, et al: The PTSD Checklist: reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, October 24 to 27, 1993Google Scholar

45. Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Rosenberg SD, et al: Psychometric evaluation of trauma and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder assessments in persons with severe mental illness. Psychological Assessment 3:110-117, 2001Crossref, Google Scholar

46. Blanchard EP, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, et al: Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist. Behavior Therapy 34:669-673, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

47. Goodman LA, Thompson KM, Weinfurt K, et al: Reliability of reports of violent victimization and PTSD among men and women with SMI. Journal of Traumatic Stress 12:587-599, 1999Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

48. Kraemer HC: Pitfalls of multisite randomized clinical trials of efficacy and effectiveness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 26:533-541, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

49. Fillmore K, Johnstone B, Leino E, et al: A cross-study contextual analysis of effects from individual-level drinking and group-level drinking factors: a meta-analysis of multiple longitudinal studies from the Collaborative Alcohol-Related Longitudinal Project. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 54:37-47, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

50. Gentry M, Kalsbeek W, Hogelin G, et al: The behavioral risk factor surveys: II. design, methods, and estimates from combined state data. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 1:9-14, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

51. Hasselblad V, McCrory DC: Meta-analytic tools for medical decision making: a practical guide. Medical Decision Making 15:81-96, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

52. Ioannidis J, Cappelleri J, Lau J: Issues in comparisons between meta-analyses and large trials. JAMA 279:1089-1093, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

53. Korn E, Graubard B: Epidemiologic studies utilizing surveys: accounting for the sampling design. American Journal of Public Health 81:1166-73, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

54. Leaf P, Myers J, McEvoy L: Procedures used in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study, in Psychiatric Disorders in America: The Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study. Edited by Robins LN, Regier DA. New York, Free Press, 1991Google Scholar

55. Simpson J, Donner A: Accounting for cluster randomization: a review of primary prevention trials, 1990 through 1993. American Journal of Public Health 85:1378-1383, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

56. Streiner D: Using meta-analysis in psychiatric research. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 36:357-362, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

57. Swanson JW: Mental disorder, substance abuse, and community violence: an epidemiological approach, in Violence and Mental Disorder: Developments in Risk Assessment. Edited by Monahan J, Steadman H. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994Google Scholar

58. Swanson, JW, Estroff SE, Swartz MS, et al: Violence and severe mental disorder in clinical and community populations: the effects of psychotic symptoms, comorbidity, and lack of treatment. Psychiatry 60:1-22, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

59. Erez A, Bloom M, Wells M: Using random rather than fixed-effects models in meta-analysis: implications for situational specificity and validity generalization. Personnel Psychology 49:275-306, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar