Consumer-Run Service Participation, Recovery of Social Functioning, and the Mediating Role of Psychological Factors

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the relationship between participation in consumer-run services and recovery of social functioning among persons diagnosed as having serious mental illness. It also assessed the role of psychological factors in mediating this relationship. METHODS: Research questions investigated were whether involvement in consumer-run services is positively associated with recovery when premorbid and demographic factors are controlled for, whether psychological factors are positively associated with recovery irrespective of involvement in consumer-run services, and whether the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and recovery is mediated by the psychological factors. The factors examined were self-efficacy, hopefulness, and active coping strategies. Sixty participants with a past or present diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder and at least one past psychiatric hospitalization were recruited from a community mental health center and two consumer-run programs. Data were collected on hopefulness, self-efficacy, coping strategies, social functioning, and premorbid and demographic characteristics. RESULTS: Findings indicated that participants involved in consumer-run services had better social functioning than those involved only in traditional mental health services, that psychological variables were significantly associated with social functioning, and that the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and social functioning was partly mediated by the use of more problem-centered coping strategies. Premorbid and demographic factors did not account for the relationship between psychosocial variables and social functioning, although education was a significant predictor of social functioning. CONCLUSIONS: The findings support the view that psychosocial factors may play a role in facilitating good community adjustment for individuals diagnosed as having serious mental illness.

Since the late 1980s, several authors have discussed the concept of recovery from serious mental illness, stressing that recovery is an idea with important implications for mental health services and policy (1,2,3). Nevertheless, very few data exist on why some individuals diagnosed as having serious mental illness achieve favorable outcomes while others do not. Despite the absence of hard data, exploratory studies of the process of recovery and autobiographical accounts by individuals who have recovered have consistently underscored the importance of certain factors, providing leads for further investigation.

A potential recovery-facilitating factor that is consistently highlighted in autobiographical accounts (4,5,6,7,8) is involvement in self-help services and other types of consumer-delivered mental health services. By providing opportunities for interaction with recovering peers, services such as self-help organizations are believed to have an impact on several psychological factors, including empowerment, a concept related to self-efficacy (9,10); hopefulness; and the informal learning of adaptive coping strategies (7). Uncontrolled studies of self-help organizations and drop-in centers have yielded consistently positive findings (11,12,13,14,15,16), and two controlled studies found that involvement in self-help services was related to lower hospitalization rates (17,18).

The general importance of psychological characteristics believed to be acquired through involvement in consumer-run services has also been suggested by qualitative studies (19,20,21) and autobiographical accounts (4,5,6,7,8) indicating that hopefulness, self-efficacy, and the use of active coping strategies can facilitate recovery. Studies exploring the use of coping strategies among persons with serious mental illness have also noted an association between active coping and good community adjustment (22,23,24,25), although the causal direction of this relationship was not assessed.

We designed this investigation to improve understanding of the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and recovery from serious mental illness. We drew our sample from individuals receiving consumer-run services or traditional mental health services only. We assessed the psychological factors of hopefulness, self-efficacy, and the use of active coping strategies as possible mediators of the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and recovery. Because our design was cross-sectional, we controlled for premorbid and demographic factors that have consistently been found to predict favorable outcomes (26,27)—including age at first hospitalization, education, and premorbid marital status—and that may be related to both the acquisition of psychological factors and successful recovery.

Hypotheses were based on the view that psychological factors believed to be stimulated by involvement in self-help services play a real and important role in the process of recovery. We also considered biological and genetic factors to be important; however, we did not expect them to wholly account for the impact of variables related to personal agency.

We hypothesized that involvement in consumer-run services would be associated with better community adjustment when the analysis controlled for premorbid variables. We also hypothesized that the psychological variables studied would be generally associated with better community adjustment when the analysis controlled for premorbid variables. Finally, we hypothesized that the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and community adjustment would be partially mediated by the psychological variables studied.

Although there is as yet no consensus on how to define recovery, for the purposes of this investigation recovery was operationally defined as good community adjustment rather than as the absence of psychiatric symptoms (28). This definition is consistent with the definition of recovery that has been offered by Anthony (1) and with the disability rights perspective (29).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two sources: a community mental health center (CMHC) located in the Hudson Valley region of New York State and two consumer-run programs in the same region. Participants were also recruited from a consumer-led self-help group for persons with bipolar disorder. The two consumer-run programs are staffed and operated completely by self-described mental health consumers. They provide services such as self-help, activity groups, and drop-in groups. The majority of individuals receiving services from these agencies also receive professional mental health services.

Only English-speaking individuals between the ages of 21 and 67 with a past or present diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or bipolar disorder and at least one past psychiatric hospitalization were eligible for the study. The criterion of allowing for a past but not necessarily a present diagnosis was based on evidence suggesting that diagnoses often change over the life span (30). We included these individuals because it is possible that some people who recover from serious mental illness are told that they were originally misdiagnosed as a result of clinical prejudices related to the belief that it is not possible for a person diagnosed as having schizophrenia to achieve high social functioning (8).

CMHC records that provided demographic data as well as detailed information on diagnostic history and hospitalizations were used to draw a random sample of all persons who met inclusion criteria. Individuals in the sample were from a continuing treatment program, an outpatient program, and a special services program. Of 69 eligible individuals randomly selected from CMHC records, ten (14 percent) were not approached because the treating clinician did not give permission. In most of these cases, the clinician believed that the person was not psychiatrically stable and might be upset by the interview.

Of the 59 remaining individuals, four were not contacted because no telephone number or accurate address was available. Of the 55 individuals approached, 20 (36 percent) refused to participate. Thus 35 individuals from the sample (64 percent of those contacted and 51 percent of those eligible) were interviewed for the study. Two of the participants recruited from the CMHC reported that they currently attended mental health self-help groups or consumer-run services.

Because the consumer-run programs did not keep records on participants, different recruitment methods were used for this sample. Flyers were posted and announcements were made at meetings. Persons who contacted us about participating underwent a brief screening that assessed past diagnosis and hospitalization history to determine eligibility. Of the 26 individuals meeting eligibility criteria who contacted us, only one refused to participate in the study after the screening. Thus this study group had 25 participants.

A total of 60 individuals were interviewed between October 1997 and May 1998. Twenty-seven (45 percent) reported current participation in consumer-run services. The overall sample was evenly divided by gender—30 were men and 30 were women. A total of 44 participants (73 percent) identified themselves as European American, seven (11.7 percent) as African American, and nine (15.3 percent) as members of other ethnic groups.

Assessments

Participants were asked about their age, ethnicity, years of education, age at first psychiatric hospitalization, years of education at first hospitalization, number of past hospitalizations, and marital status at first hospitalization. Participants were also asked about their parents' occupations during the participant's childhood for an assessment of parental socioeconomic status; parents' occupational titles were coded on a 5-point scale based on a standard occupational status classification system (31). Current diagnosis was based on available clinic records for all participants currently receiving services from the CMHC, a group that included nine persons who attended self-help services. If records on diagnosis were not available, participants were asked to report their current diagnosis to the best of their knowledge.

For each participant, the Herth Hope Index (32,33), the Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale (34), and the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (35) were administered, with the interviewer reading the items out loud. The Herth Hope Index is a brief, 12-item self-report measure that has been found to have good internal consistency (alpha=.97) and convergent and divergent validity (for example, r= -.73 with the Beck Hopelessness Scale); the Herth Hope Index has been used with a sample of individuals diagnosed as having serious mental illnesses (33). Items assess positive expectations, inner sense of temporality, and interconnectedness with self and others (for example, "I believe that each day has potential").

The Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale, a 10-item self-report measure, has been found to have good internal consistency (alpha between 75 and .90) and criterion-related validity. Items assess beliefs about personal effectiveness in dealing with challenges and problems (for example, "I am confident that I could deal efficiently with unexpected events").

The SFS is a relatively brief, objectively scored self-report measure that addresses multiple facets of community adjustment, including social engagement and withdrawal, interpersonal behavior, prosocial activities, recreation, independence, and employment or occupation. It has been normed on samples of individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia and individuals with no diagnosis living in the general population. It has been found to have good internal consistency (alphas for subscales range from .69 to .85) and criterion-related validity. Raw scores for each subscale are converted to a standard score; overall social functioning is based on the mean standard score.

Coping was assessed with a strategy described in previous research involving persons with serious mental illness (24,25): participants were asked whether they experienced certain common symptoms—questions were drawn from the work of Cohen and Berk (22) and Carr (36). They were then asked about the types of strategies they used to cope with these symptoms. Coping interviews were transcribed and content-coded by the interviewer and an independent rater on two dimensions: a problem-centered-non-problem-centered dimension and a cognitive-behavioral-emotional dimension. This system has been described by Wiedl and Schöttner (25). Ratings by the experimenter and the independent rater (a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology with research experience) were identical for 81 percent of the cases. For cases in which the two raters disagreed, a third rater (also a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology with research experience) acted as an arbiter. As recommended in the literature (24,37,38), a ratio of problem-centered behavioral and cognitive coping strategies divided by the total number of coping strategies was computed for each participant to create an index of problem-centered coping (problem-centered coping ratio).

For exploratory purposes, participants were asked what factors they perceived to be most important in any progress they had made since their first hospitalization. Responses were recorded and later content-coded by the investigator.

Analysis plan

Means, modal percentages, standard deviations, and ranges were computed for all variables to describe the study sample. To better describe the social functioning of the sample, data from the SFS were used to separate participants into outcome categories. Cutoffs were based on ranges identified in the study in which the SFS was normed (35). Scores of 55 to 105 indicated moderately impaired functioning, according to the finding in the original study that the lowest functioning 56.6 percent of the schizophrenia sample and only 7 percent of the general community sample scored within this range. Scores of 106 to 115 indicated mildly impaired functioning. Scores of 116 to 135 indicated minimally impaired functioning, according to the finding in the original study that 74 percent of the general population sample fell within this range.

Chi square and t tests were conducted to assess differences in the associations of psychological, demographic, and premorbid variables with self-help attendance. To account for multiple statistical tests, a conservative p value of .01 was used.

Bivariate intercorrelations were computed for all variables. Multivariate linear regression analyses were then conducted to examine the relationship between predictor variables and SFS score; the SFS was found to meet assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, and linearity. The first regression analysis assessed whether the proportional use of problem-centered coping strategies and self-efficacy accounted for variation in social functioning when the analysis controlled for premorbid factors. The second set of analyses assessed the relationship between self-help attendance and social functioning and tested the hypothesis that the proportional use of behavioral and cognitive problem-centered coping strategies partly mediated the relationship between self-help attendance and social functioning.

Results

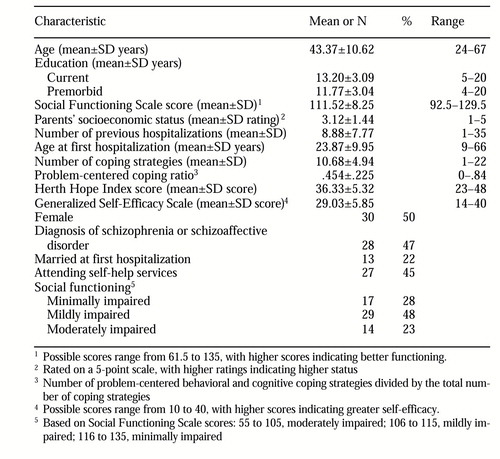

Table 1 presents means, frequencies, standard deviations, and ranges for all variables. Typical participants had a current diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, had graduated from high school, had experienced multiple psychiatric hospitalizations, and had been first hospitalized in their early twenties. Nearly half the sample had mildly impaired social functioning.

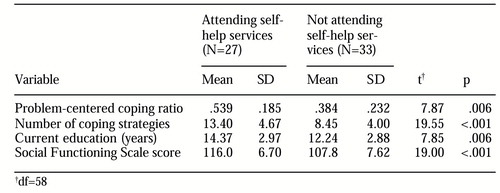

Table 2 presents all significant differences between those who attended self-help services and those who did not. No significant differences were found for age, hopefulness, number of past hospitalizations, age at first hospitalization, gender, diagnosis, premorbid education, parents' socioeconomic status, or premorbid marital status. Self-help attenders and nonattenders differed significantly in the proportion of problem-centered coping responses reported, the total number of coping strategies used, current education, and social functioning; self-help attenders had higher scores, indicating better status on all variables. Involvement in self-help services was clearly associated with better community adjustment, with the use of more coping strategies, and with a greater proportion of problem-centered coping. Education may have operated as a selection variable for self-help attendance.

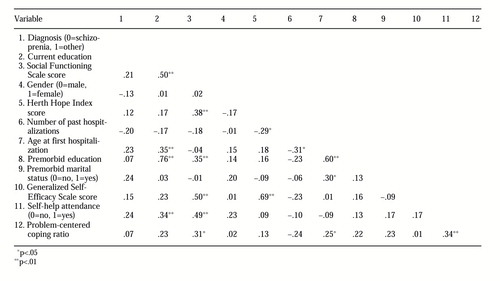

Bivariate correlations are reported in Table 3. All the psychosocial variables were significantly correlated with SFS score. (Psychosocial variables included the psychological variables plus the self-help variable.) However, the only premorbid and demographic variables associated with SFS score were current and premorbid education. Problem-centered coping and self-help involvement were significantly correlated, although neither was significantly correlated with self-efficacy or hopefulness. Age at first hospitalization was significantly correlated with problem-centered coping. Self-efficacy and hopefulness were highly correlated, suggesting that collinearity might be a problem in interpreting the coefficients if these variables were entered in the same regression equation. Current and premorbid education were also highly correlated, indicating that they measured the same construct.

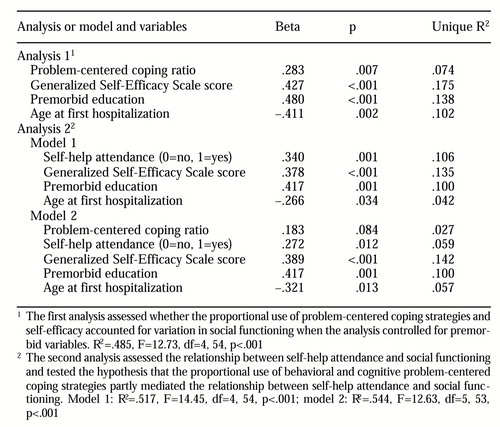

A series of regression analyses were conducted to address whether self-help attendance and the psychological variables significantly predicted social functioning when the analyses controlled for premorbid and demographic factors. Findings from these analyses are summarized in Table 4.

Premorbid and demographic variables that were significantly correlated with social functioning or with one of the psychological variables—premorbid education and age at first hospitalization—were included as control variables for statistical power considerations and because preliminary analyses indicated that including all control variables did not significantly alter the findings. Current education was not included because it may partly reflect actions taken after the onset of psychiatric illness, and it was highly correlated with premorbid education.

As shown in Table 4, the first analysis found the proportional use of problem-centered coping strategies and self-efficacy to be significant predictors of social functioning even when the analysis controlled for the premorbid variables. Problem-centered coping strategies and self-efficacy uniquely explained about 7.5 percent and 17 percent, respectively, of the variance in SFS score. This finding suggested that a substantial proportion of the effect of the psychological factors was not explained by premorbid variables. Hopefulness was not included in this analysis because of its collinearity with self-efficacy; however, a separate analysis found that hopefulness also contributed a statistically significant unique variance when the analysis controlled for premorbid variables.

The second set of analyses shown in Table 4 explored whether self-help attendance significantly predicted social functioning, and if so, whether its effect was mediated by the use of problem-centered coping strategies. Criteria needed to demonstrate mediation were taken from the literature (39). The four criteria are evidence of a significant relationship between the predictor and the mediator, evidence of a significant relationship between the predictor and the dependent variable, evidence of a significant relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable, and evidence that the effect of the predictor is markedly reduced when the mediator is controlled for. The first and third criteria were supported by findings of a significant correlation between self-help attendance and problem-centered coping and a significant relationship between problem-centered coping and social functioning (Table 3). The first analysis shown in Table 4 indicated that self-help attendance was a statistically significant predictor of social functioning when the analysis accounted for the control variables. This finding supported the second criterion, evidence of a significant relationship between the predictor and the dependent variable. Finally, the second model shown in the second analysis in Table 4 indicated that when self-help and coping were both entered into the equation, the unique variance in social functioning explained by self-help attendance was reduced from roughly 10.5 percent to about 6 percent. This finding supported the fourth criterion, indicating that problem-centered coping partly mediated the effect of self-help attendance on social functioning.

Discussion and conclusions

The first and second hypotheses of this study were that involvement in consumer-run services would be associated with better community adjustment when analyses controlled for premorbid variables and that the psychological variables would also be generally associated with better community adjustment when analyses controlled for premorbid variables. The two hypotheses were supported by the finding that the psychological variables and involvement in consumer-run services were significantly associated with social functioning even when the analyses controlled for the effect of premorbid and demographic variables. Only partial support was found for the third hypothesis, which was that the relationship between involvement in consumer-run services and community adjustment would be partly mediated by the psychological variables. Although we found clear evidence that the use of problem-centered coping strategies partly mediated the relationship between self-help attendance and social functioning, no evidence was found that either hopefulness or self-efficacy accounted for the relationship between self-help attendance and social functioning.

These findings suggest that self-efficacy and hopefulness and the active use of coping strategies had an independent relationship with social functioning. One possible explanation is that the measure of generalized self-efficacy we used was not specifically related to coping with psychiatric symptoms. A measure developed to address a person's expectations of having the ability to handle such symptoms in a more specific way would provide a truer test of the association between coping and self-efficacy in the context addressed in this study.

Another possible explanation is that the discrepancy reflects the existence of two different paths to recovery. One path may be taken by individuals who have a high sense of self-efficacy and who feel more confident because their symptoms are more effectively managed by medication and who therefore have less of a need to cope in an active manner. The other path may be taken by individuals who cope more actively while experiencing more symptoms; such individuals may feel less confident about their ability to manage symptoms but may nevertheless work more actively to deal with them.

Although our analyses indicated that the use of problem-centered coping strategies partly mediated the relationship between self-help attendance and social functioning, coping did not wholly explain this relationship. This finding suggests that there may be processes related to self-help involvement that affect community adjustment that were not studied in this investigation. One variable discussed in the self-help literature (6,40) that was not studied here is social support. Future research should measure social support to assess the degree to which it accounts for the association between social functioning and involvement in self-help services.

The only premorbid or demographic predictors that were associated with outcome in this study were current and premorbid education. Although the statistical relationship between the psychosocial variables and social functioning was not wholly explained by current and premorbid education, premorbid education did emerge as an important predictor. Although differences in premorbid education might be suspected to be the result of differences in socioeconomic status, no differences were found in parent's socioeconomic status between any of the groups with different outcomes.

It is possible that differences in premorbid education reflect differences in the type of onset of illness—that is, gradual or acute. Participants in the moderately impaired group were more likely not to have completed high school than those in the mildly impaired and minimally impaired groups. This finding may indicate that the moderately impaired participants had been in the early stages of a psychiatric disorder with a gradual onset when they left school. Gradual onset of a psychiatric disorder has been found to be an important predictor of poor outcome (26), but it was not directly studied in this investigation. Future investigations should incorporate appropriate measures to assess the relationship between type of onset and psychological variables.

The relationship between the psychosocial variables and community adjustment was evident even when the analysis controlled for premorbid characteristics. This finding provides tentative support for the view that psychosocial factors may facilitate good community adjustment for individuals with serious mental illness.

The quantitative findings in this study were complemented by information obtained from the exploratory question at the end of the interview, which asked participants to identify factors related to their improvement. Eight, or 47 percent, of the participants who may be considered to have recovered—that is, who are in the minimally impaired range of social functioning—identified a psychological factor as the most important factor in their overall improvement. In contrast, only one, or 7 percent, of those functioning in the moderately impaired category identified a psychological factor. Psychological factors discussed included the importance of using coping strategies to deal with symptoms and personal realizations that fueled subsequent efforts to deal with disability. One recovered participant's statements are particularly illuminating: "I think the one thing that has helped my recovery above anything else is the philosophy that I have to take responsibility for my own recovery, that I have to take the reins. I have to take 95 percent of the responsibility."

Our findings support the view that mental health services that aim to help people learn how to cope effectively with symptoms, become more hopeful, and gain a greater sense of self-efficacy may increase an individual's chances of obtaining a positive outcome. There is a growing body of evidence from controlled studies demonstrating that psychotherapeutic treatments that pursue these or related aims lead to significant gains in social functioning (41,42). However, these treatments have yet to become widely adopted in mental health practice (43). Similarly, although the number of consumer-run services has grown rapidly in recent years (44), considerable skepticism still exists among many in the mental health field about whether such services should continue to be publicly funded.

This study represents only a first step in the difficult task of examining the connection between involvement in consumer-run services and recovery from serious mental illness. The study had several limitations. First, its sample size was relatively small, limiting generalizability and restricting the statistical power of the analyses. This type of study needs to be replicated with a larger and more representative sample. Furthermore, the inconsistent manner in which participants were selected from the two sample sources is problematic—one group was chosen randomly and the other drawn from volunteers. Although demographic data indicated that the samples did not differ significantly, it is possible that the samples differed in other, unmeasured ways. Symptom severity, insight, and neurocognitive functioning (45) are important variables that may affect social functioning, and they were not directly assessed in this study.

Future research should seek to measure additional factors that may be related to self-selection, and the investigators should enter into cooperative relationships with consumer-run agencies so that participants can be selected randomly. Finally, it should be reiterated that attempts to draw causal inferences from cross-sectional designs such as that used in this study are tentative at best and that prospective designs are required to address these issues.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Mental Health Empowerment Project. The authors thank Jamie Walkup, Ph.D., Allan Horwitz, Ph.D., and David Mechanic, Ph.D., for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper; and Benjamin Hayden, Ph.D., Bill Iaccino, Ph.D., Chris Kaeppner, Ph.D., and Victoria Frye, M.P.H., for their assistance in planning and implementing the study.

Dr. Yanos is affiliated with the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University, 30 College Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901 (e-mail, [email protected]). When this work was done Dr. Primavera was professor of psychology at St. John's University in Jamaica, New York. He is now with the Derner Institute at Adelphi University in Garden City, New York. Dr. Knight is director of the Mental Health Empowerment Project in Albany, New York. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the annual meeting of the American Public Health Association held November 15-18, 1998, in Washington, D.C.

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a sample of 60 persons with severe mental illness drawn for a study of participation in consumer-run services

|

Table 2. Significant differences between study participants by whether or not they were attending self-help services

|

Table 3. Correlation matrix of all variables associated with social functioning among study participants

|

Table 4. Two linear regression analyses of relationship between the characteristics of study participants and scores on the Social Functioning Scale

1. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16(4):11- 23, 1993Google Scholar

2. Harding CM, Zubin J, Strauss JS: Chronicity in schizophrenia: fact, partial fact, or artifact? Hospital and Community Psychiatry 38:477-485, 1987Google Scholar

3. Strauss JS: Subjective experiences of schizophrenia: toward a new dynamic psychiatry. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:179-187, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Anonymous: How I've managed chronic mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:635-640, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Deegan PE: Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11(4):11-19, 1988Google Scholar

6. Chamberlain J: On Our Own: Patient-Controlled Alternatives to the Mental Health System. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1978Google Scholar

7. Fisher DB: A new vision of healing as constructed by people with psychiatric disabilities working as mental health providers. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 17(3):67-81, 1994Google Scholar

8. Lovejoy M: Recovery from schizophrenia: a personal odyssey. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 35:809-812, 1984Abstract, Google Scholar

9. Segal SP, Silverman C, Temkin T: Measuring empowerment in client-run self-help agencies. Community Mental Health Journal 31:215-227, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Rosenfield S: Factors contributing to the subjective quality of life of the chronically mentally ill. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 33:299-315, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Galanter M: Zealous self-help groups as adjuncts to psychiatric treatment: a study of Recovery, Inc. American Journal of Psychiatry 145:1248-1253, 1988Link, Google Scholar

12. Kurtz LF: Mutual aid for affective disorders: the Manic-Depressive and Depressive Association. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 58:152-155, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Raiff NR: Some health-related outcomes of self-help participation: Recovery, Inc, as a case example of a self-help organization in mental health, in The Self-Help Revolution. Edited by Gartner A, Riessman F. New York, Human Sciences, 1984Google Scholar

14. Rappaport J, Seidman E, Toro PA, et al: Collaborative research with a mutual-help organization. Social Policy 15:12-24, 1985Medline, Google Scholar

15. Chamberlain J, Rogers ES, Ellison ML: Self-help programs: a description of their characteristics and their members. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19(3):34-42, 1996Google Scholar

16. Mowbray CT, Tan C: Consumer-operated drop-in centers: evaluation of operations and impact. Journal of Mental Health Administration 20:8-18, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Kennedy M: Psychiatric hospitalizations of GROWers. Presented at the Second Biennial Conference on Community Research and Action, East Lansing, Mich, 1989Google Scholar

18. Edmunson ED, Bedell JR, Archer RP, et al: Integrating skill building and peer support in mental health treatment: the Early Intervention and Community Network Development projects, in Community Mental Health and Behavioral-Ecology: A Handbook of Theory, Research, and Practice. Edited by Jeger AM, Slotnick RS. New York, Plenum, 1982Google Scholar

19. Davidson L, Strauss JS: Sense of self in recovery from severe mental illness. British Journal of Medical Psychology 65:131-145, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Sullivan WP: A long and winding road: the process of recovery from severe mental illness. Innovations and Research 2:19-27, 1994Google Scholar

21. Young SL, Ensing DS: Exploring recovery from the perspective of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 22:219-231, 1999Crossref, Google Scholar

22. Cohen CI, Berk LA: Personal coping styles of schizophrenic outpatients. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 36:407-410, 1985Abstract, Google Scholar

23. Lam D, Wong G: Prodromes, coping strategies, insight, and social functioning in bipolar affective disorders. Psychological Medicine 27:1091-1100, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Pallanti S, Quercioli L, Pazzagli A: Relapse in young paranoid schizophrenic patients: a prospective study of stressful life events, P300 measures, and coping. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:792-798, 1997Link, Google Scholar

25. Wiedl KH, Schöttner B: Coping with symptoms related to schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 17:525-538, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Pfeiffer SI, O'Malley DS, Shott S: Factors associated with outcome of adults treated in psychiatric hospitals: a synthesis of findings. Psychiatric Services 47:263-269, 1996Link, Google Scholar

27. Wieselgren IM, Lindström LH: A prospective 1-5 year outcome study in first-admitted and readmitted schizophrenic patients: relationship to heredity, premorbid adjustment, durations of disease, and education level at index admission and neuroleptic treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:9-19, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Harding CM: Speculations on the measurement of recovery from severe psychiatric disorder and the human condition. Psychiatric Journal of the University of Ottawa 11:199-204, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

29. Deegan PE: The independent living movement and people with psychiatric disabilities: taking back control of our own lives. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 15(3):3-19, 1992Google Scholar

30. Chen YR, Swann AC, Johnson BA: Stability of diagnosis in bipolar disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:17-23, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Nam CB, Powers MG: The Socioeconomic Approach to Status Measurement. Houston, Cap & Gown, 1983Google Scholar

32. Herth K: Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 17:1251-1259, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Littrell KH, Herth KA, Hinte LE: The experience of hope in adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:61-65, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

34. Schwarzer R: Measurement of Perceived Self-Efficacy: Psychometric Scales for Cross-Cultural Research. Berlin, Forschung and der Freien Universitat Berlin, 1993Google Scholar

35. Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, et al: The Social Functioning Scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programs with schizophrenic patients. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:853-859, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Carr V: Patients' techniques for coping with schizophrenia: an exploratory study. British Journal of Medical Psychology 61:339-352, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Mueser KT, Valentiner DP, Agresta J: Coping with negative symptoms of schizophrenia: patient and family perspectives. Schizophrenia Bulletin 23:329-339, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Vitaliano PP, Maiuro RD, Russo J, et al: Raw versus relative scores in the assessment of coping strategies. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 10:1-18, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

39. Holmbeck GN: Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 65:599-610, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

40. Kaufmann CL, Freund PD, Wilson J: Self-help in the mental health system: a model for consumer-provider collaboration. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 13(1):5- 21, 1989Google Scholar

41. Hogarty GE, Greenwald D, Ulrich RF, et al: Three-year trials of personal therapy among schizophrenic patients with or independent of family: II. effects on adjustment of patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:1514-1524, 1997Link, Google Scholar

42. Barton R: Psychosocial rehabilitation services in community support systems: a review of outcomes and policy recommendations. Psychiatric Services 50:525-534, 1999Link, Google Scholar

43. Lehman AF: The role of mental health service research in promoting effective treatment for adults with schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics 1:199-204, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

44. Carling PJ: Return to Community: Building Support Systems for People With Psychiatric Disabilities. New York, Guilford, 1995Google Scholar

45. Green MF: What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? American Journal of Psychiatry 153:321-330, 1996Google Scholar