A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of a Modified Recovery Workbook Program: Preliminary Findings

Recovery has gained international prominence as a guiding framework for mental health service delivery. The term "recovery" was derived from first-person narratives and was coined by Patricia Deegan, Ph.D., who defined it as the ways in which people with mental illness develop new meaning and purpose in life beyond the challenges posed by the illness ( 1 ).

Recovery is thus conceptualized as both a process and an outcome. As a process, recovery is characterized as a life-long journey, grounded in values such as hope, empowerment, and quality of life ( 2 , 3 , 4 ). Outcomes consistent with recovery include evidence that the individual is learning about the illness and engaging in efforts to manage and control the illness. Ultimately this can lead to a reduction in psychiatric symptoms, a decrease in hospitalizations, and improvements in global functioning ( 5 , 6 , 7 ). Recovery outcomes also include evidence of a hopeful attitude and engagement in activities that hold personal and social meaning. In this way, recovery is closely linked to the values of full social participation and inclusion.

Research has been undertaken to understand the dimensions of recovery. For example, Noordsy and colleagues ( 8 ) described a framework for recovery structured into three core components that can be operationalized and measured—namely, having a hopeful attitude, taking personal responsibility, and getting on with life beyond the challenges posed by illness ( 8 ). The components of this definition are consistent with the definitions of recovery in both research and consumer literature ( 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ). The definition specifically emphasizes the intrapersonal dimensions of progress toward recovery that are highlighted in the literature as essential for describing the recovery process ( 9 ).

The recovery process is thought to be influenced by both internal and external conditions. Internal conditions include the attitudes, experiences, and processes of change of individuals who are recovering, and external conditions are the circumstances, events, policies, and practices that may facilitate recovery ( 9 ). External conditions, such as access to recovery-oriented services, can foster and enhance a person's internal attributes to enable forward movement in the recovery process.

Recovery is described as a nonlinear process, unique for each individual, and one that takes place even when symptoms recur ( 13 ). The past decade has witnessed the development of service interventions focused directly on enabling the recovery process. These interventions are designed to lead to changes in areas considered to be important aspects of the recovery process. They use empirically supported methods, such as psychoeducational and cognitive-behavioral approaches, to enable the change process. Examples of recovery-oriented interventions include the Recovery Workbook ( 14 ), the Wellness Recovery Action Plan ( 15 ), the Leadership Education Program ( 16 ), and the recently developed illness management and recovery program ( 17 ). These interventions integrate services provided by professionals and consumers, and each intervention is designed to empower and enable persons with serious mental illness to take responsibility for decisions about their lives. Each intervention is focused on strengths and may be offered in a group. The objectives of the interventions include increasing knowledge about mental illness and recovery and engaging consumers in goal planning to increase their sense of potential. The interventions differ, however, in the level of engagement that each requires from the consumer and in the amount of structure provided to guide the group process. In addition, they also differ in the therapeutic techniques that guide the group process.

Surprisingly, few studies have been conducted to test the efficacy of these intervention programs. There are two notable exceptions. First, a small randomized controlled trial examined the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program ( 18 ). The study found that the program is effective in increasing participants' knowledge of their mental illness and helping them make progress toward personal goals. The study provided evidence that this intervention can enable changes consistent with those described in the literature as very important to recovery ( 7 , 19 , 20 , 21 ). Another recent study measured the extent to which symptoms and psychosocial outcomes, including hope, empowerment, and self-advocacy, improved after participation in an eight-week peer-led, mental illness self-management intervention called the Wellness Recovery Action Plan ( 22 ). The study found that participants' scores on several outcomes improved significantly; however, the study did not have a control group and therefore the results should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, both studies demonstrate that conducting research in this area is feasible and that there are several psychometrically sound outcome measures that can capture the recovery concept.

Further research using a randomized controlled trial design to fill the gap in scientific knowledge about the efficacy of recovery interventions is clearly needed. The study reported here was undertaken in response to the call for greater attention to the development of recovery-consistent services supported by empirical research ( 20 , 23 , 24 , 25 ).

We studied the effectiveness of a modified version of Spaniol and colleagues' Recovery Workbook group intervention ( 14 ). The Recovery Workbook is a well-known intervention and widely disseminated in the mental health field. Our hypothesis, which is consistent with important dimensions of recovery, was that participation in the modified version of the Recovery Workbook program would result in improvements in participants' perceived sense of hope, empowerment, recovery, and quality of life.

Methods

This study used a multicenter, prospective, single-blind, randomized controlled trial design and was conducted at two outpatient mental health sites in a small city center. Both sites met the Ontario standards for assertive community treatment (ACT) as designated by the Ontario Ministry of Health. Managers from two ACT teams screened 140 clients between August 2006 and October 2006 for study eligibility. Clients were eligible if they used ACT services for more than six consecutive months, were between the ages of 18 and 60, and met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, delusional disorder, or bipolar disorder. Clients were ineligible if they were not fluent in English, had a premorbid IQ of <65, had substance abuse or an organic disorder as the major cause of psychotic symptoms, or were considered not competent to give informed consent. The study was approved by the Queen's University Health Science Research Ethics Board and the Providence Care Research Ethics Board.

Eighty-one recipients of ACT services met the inclusion criteria. After being informed about the study, 34 chose to participate and provide informed consent. One person withdrew before randomization. Participants were compensated for their travel and childcare costs to complete the pre- and postintervention assessments. Transportation costs were paid for participants who were randomly assigned to the intervention group. However, no other incentives were offered to participate in the study.

Intervention

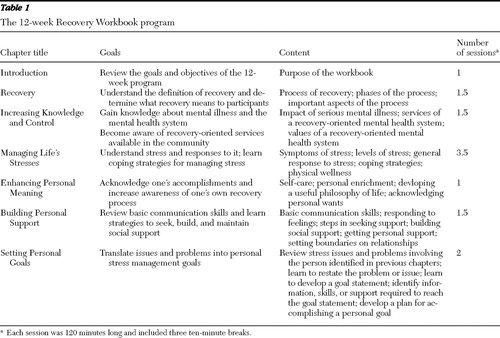

The Recovery Workbook uses an educational process to increase awareness of recovery, increase knowledge and control of the illness, increase awareness of the importance and nature of stress, enhance personal meaning, build personal support, and develop goals and plans of action ( 14 ). The intervention period of 30 weekly sessions recommended by Spaniol and colleagues ( 14 ) was shortened to 12 weekly sessions to accommodate for clinical and participant commitment. No workbook content was excluded, and all practice exercises were covered. Compared with the 30-week recommended program, the 12-week program offered less time for discussion and practice during the group; however, each participant was encouraged to review the material and practice between sessions. Each session included a combination of teaching, group discussion, and practice exercises as outlined by Spaniol and colleagues ( 14 ). An overview of the modified program is provided in Table 1 .

|

The training included 12 weekly two-hour group sessions with seven to nine participants. Each session was conducted by the first author, who is an occupational therapist who provided services to another ACT team that did not participate in the study, and by a peer support worker, who was a paid member of an ACT team in the study.

Procedure

After the list of eligible participants was identified and informed consent was obtained, the participants were grouped on the basis of which team they received ACT services from. Next, participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. Participants in the control group continued to receive their usual treatment as determined by the ACT team, and the experimental group received the Recovery Workbook training in addition to usual care from the ACT team.

Sociodemographic and clinical information for each participant was collected in an interview before completion of the baseline assessments. Diagnosis, age, age at first hospitalization, and number of hospitalizations were verified in the medical charts by the assertive community treatment team manager. Study assessments were conducted one week before randomization and within three days of completion of the intervention. Three assessors, who were blind to the treatment condition, conducted assessments of all study groups. Assessors received a one-hour training session about the purpose, reliability, and validity of each tool before the study began.

Measures

Hope. The Herth Hope Index ( 26 ) was used to gather information about participants' level of hopefulness. The 12-item scale is easily administered and has been used with persons with serious mental illness ( 27 , 28 , 29 ). It is a self-report tool, and respondents answer on a 4-point agreement scale. The scale has been shown to have an alpha coefficient of .97 and a test-retest reliability of .91 within two weeks ( 30 ). Criterion-related validity has also been supported by high correlations (.81–.92) with instruments measuring the same construct ( 26 , 30 ).

Empowerment. The Empowerment Scale ( 31 ) contains 28 statements about empowerment to which participants respond on a 4-point agreement scale. Studies have demonstrated the scale's high internal consistency (Cronbach's α =.85–.90) and good reliability ( α >.60) and validity ( 28 , 31 , 32 ).

Recovery. The Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) has 41-items measuring coping ability, sense of empowerment, and quality of life. The scale uses a 5-point agreement scale, and a total score is used. Factor analysis of this scale resulted in five factors: personal confidence and hope, willingness to ask for help, ability to rely on others, not dominated by symptoms, and goal and success orientation ( 33 ). The RAS has good test-retest reliability ( α =.88) and excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α =.93) ( 20 , 28 ). McNaught and colleagues ( 34 ) determined that the RAS produced five factors that were replicated by using confirmatory techniques; each factor has satisfactory internal reliability (Cronbach's α =.73–.91). In terms of face validity, the scale reflects many of the key concepts of recovery, such as hope, empowerment, social support, and skills for coping with illness ( 34 , 35 , 36 ).

Quality of life. The Quality of Life Index, General Version ( 37 ), is a 33-item self-report scale measuring satisfaction with and importance of aspects of life. It includes four subscales: health and functioning, socioeconomic status, psychological status, and significant others. Satisfaction and importance are measured on a 6-point agreement scale. Importance ratings are used to weight satisfaction responses so that scores reflect satisfaction with aspects of life that are valued by the individual ( 37 ). For internal consistency and reliability, Cronbach's alpha is .92 for the entire tool and .88, .75, .80, and .68, respectively, for the subscales ( 37 ).

Analyses

All statistical analyses were intent-to-treat analyses. Data were analyzed with SPSS, version 14.0, for Windows. Demographic differences between the teams and between the intervention and control groups were analyzed by using t tests and chi square tests. Normally distributed numeric data were analyzed with t tests and are reported as means and standard deviations. Dichotomous data were analyzed by chi square tests and are reported as counts with percentages. Variables measured at two points were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance, with time as a factor. Statistical significance was assessed at .05. In an additional sensitivity analysis, missing values for the primary outcome measures were replaced by the median of the sample. Before analysis, the data were screened for violations of assumptions required for univariate and multivariate analyses as recommended by Tabachnik and Fidell ( 38 ). Data were plotted, and univariate outliers with z >3.0 were excluded. Multivariate outliers were identified by use of Mahalanobis distance (p<.001 criterion). Effect size ranges were determined by using Cohen's suggested ranges ( 39 ), which state that the larger the effect size, the greater the impact of the intervention (small=.1–.3, medium=.3–.5, large >5).

The overall effects of Recovery Workbook training on perceived level of hope, empowerment, recovery, and quality of life were analyzed by using repeated-measures analysis of variance, with time of testing as the repeated-measure factor and with treatment team and group (intervention or control) as the between-subjects factors. Initial models tested a variety of other factors, such as gender, diagnosis, number of years with a psychiatric disability, and number of hospitalizations, to compare the intervention and control groups. However, these models were excluded from reported analyses because they did not change the results significantly.

Results

Of the 81 participants who met inclusion criteria, 33 participated; 17 were assigned to the control group and 16 to the intervention group. None of the participants had previously received Recovery Workbook training. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of participants. No differences were found between the intervention and control groups in demographic characteristics, with the exception of the self-reported number of years with a psychiatric disability. The intervention group had significantly more years of living with a disability (F=4.47, df=1 and 32, p=.04). At baseline no significant demographic differences were noted between the two assertive community treatment teams.

|

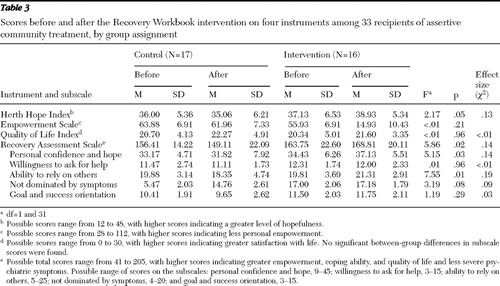

Statistically significant interactions between group and time were found for hope (F=2.17, df=1 and 32, p=.05, η2 =.13), empowerment (F=14.93, df=1 and 32, p<.001, η2 =.21), and recovery (F=5.86, df=1 and 32, p=.02, η2 =.14), in addition to significant changes in scores on the RAS subscale categories of personal confidence and hope (F=5.15, df=1 and 32, p=.03, η2 =.13) and goal and success orientation (F=7.51, df=1 and 32, p=.01, η2 =.19). No interaction between group and time was found for the total Quality of Life Index measure or any of its subscales. The means and standard deviations in Table 3 indicate the source of these interactions. Statistical interactions between group and time were found, indicating that changes over time in scale measures were dependent on group. Hope, empowerment, and recovery scores improved significantly more for participants in the intervention group than for those who received treatment as usual. In particular, participants appeared to have an increased sense of empowerment as a consequence of the intervention ( η2 =.21).

|

Separate analysis for the two sites showed no interaction between team and time for any of the four measures. Thus the results reflect a main effect for the treatment group and not the service delivery team.

Discussion

Proponents of the recovery framework have suggested that measuring relapse, recidivism, and hospitalization rates do not provide a complete measure of recovery ( 12 , 40 ). Such measures miss important indicators, such as perceived hope, empowerment, and quality of life that more fully capture the importance of fulfilling the potential to live a meaningful life beyond one's illness. This study specifically selected these outcomes in order to more fully capture the dimensions associated with the recovery process.

This study found that at least in the short term, the modified Recovery Workbook program was an effective group intervention for facilitating recovery of persons with serious mental illness. The findings suggest that the modified Recovery Workbook is an effective tool to specifically facilitate change in personal confidence and hope, empowerment, goal and success orientation, and recovery in this population. These results are independent of the passage of time and of the treatment team. The study findings suggest that 12 weeks of the modified intervention provides enough time for participants to demonstrate positive change. This is an important finding given that demands on service delivery time may determine whether a particular intervention is implemented. It is important to know that recovery initiatives that are less intense and demanding can still provide positive recovery-related results.

This study did not find differences between the control and intervention groups in quality of life. The concept of quality of life was conceptualized and measured from the perspective of both subjective experience and objective life conditions. Although the Recovery Workbook is designed to engage participants in processes involved in goal setting and action planning, it may not move them along to the point at which they can experience measurable and significant life changes, such as improved socioeconomic status, health and functioning, and relationships with significant others. The original 30-week intervention may provide the time necessary to see these types of changes; however, further research is required to test this hypothesis.

This study found no significant differences between the control and intervention groups in demographic characteristics, except for the number of years with a psychiatric disability. Compared with the control group, the intervention group had on average 6.5 more self-reported years with a disability and almost twice the reported number of admissions to a psychiatric hospital. These findings may be important because they suggest that the positive changes are partly attributable to the number of years with a psychiatric disability and the number of psychiatric admissions. However, these baseline differences provide further support for the intervention, because even though the experimental group had experienced more years of disability, they showed significant improvement in these measures of recovery.

A common question among mental health care professionals is "How do I practice recovery?" This study has shown that the Recovery Workbook intervention can be implemented in a community-based mental health setting within evidence-based services such as ACT. The workbook provides clear directions that can be implemented by mental health practitioners. In addition, the intervention is relatively inexpensive and does not require specialized training for facilitators. There has been some controversy about the potential of ACT to offer services that are truly recovery oriented ( 41 , 42 ). The Recovery Workbook is a group intervention that can be easily integrated into ACT. In this study, the Recovery Workbook program was positively received by both teams and may be a tool that can be used by such teams to focus recovery efforts.

Demonstrating the use of recovery principles in mental health practice is important. In a mental health system in which recovery is the primary goal and organizing framework, recovery-based interventions such as the Recovery Workbook should be carefully considered as treatment options. Consistent with the findings of a study by Hasson-Ohayon and colleagues ( 18 ) that examined the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program, the results of this study point to another treatment option to promote recovery. However, in order to deem these interventions evidence-based standards of care, larger longitudinal studies with various subpopulations of persons with serious mental illness are needed.

The study had several limitations. It examined a modified version of the Recovery Workbook ( 14 ) that gave participants less time to discuss topics and practice activities. A second limitation was the lack of postintervention follow-up. Also, the study was conducted in a small city center in Canada, and the social and racial-ethnic characteristics of the sample do not reflect those of the North American population. In addition, clients with comorbid substance abuse were not included in the study, and because the incidence of co-occurring disorders is so high in many North American locales, a potentially important group of persons who use mental health services may have been excluded ( 43 ). Another limitation is that all study participants were receiving assertive community treatment services. Recipients of these services are typically individuals with serious mental illness who are high service users. Caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings across all mental health services. Finally, the participation rates for the study were moderately low, and no information about nonparticipants was collected. Therefore, the sample may have been prone to selection bias.

Conclusions

This study showed that a modified version of the Recovery Workbook group program was effective in increasing individuals' perceived sense of personal confidence and hope, empowerment, goal and success orientation, and recovery. However, participation in the program did not lead to significant gains in quality of life. The study further demonstrated that the modified Recovery Workbook has the potential to be easily implemented in assertive community treatment and community mental health services. In an era in which recovery is the primary goal around which reformed service delivery is organized, recovery-based interventions such as the Recovery Workbook should be carefully considered as treatment options for persons who use mental health services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors thank Michela David, Ph.D., Heather Stuart, Ph.D., Margaret Jamieson, Ph.D., David Barbic, M.D., Carol Mieras, M.Sc.O.T., and Nicole Zwiep, M.Sc.O.T., for their assistance with this project. They also thank the staff and clients of Providence Care Mental Health Services and Frontenac Mental Health Services in Kingston, Ontario, for their efforts in making the study possible.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Deegan PE: Recovery: the lived experience of rehabilitation. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 11:11–19, 1988Google Scholar

2. Ochocka J, Nelson J, Janzen, R: Moving forward: negotiating self and external circumstances in recovery. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 28:315–322, 2005Google Scholar

3. Onken SJ, Dumont JM, Ridgeway P, et al: Mental Health Recovery: What Helps and What Hinders. A National Research Project for the Development of Recovery Facilitating System Performance Indicators. Alexandria, Va, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2002Google Scholar

4. Anthony WA: A recovery-orientated service system: setting some system level standards. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:159–168, 2000Google Scholar

5. Corrigan PW: Impact of consumer-operated services on empowerment and recovery of persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 57:1493–1496, 2006Google Scholar

6. Whitehorn D, Lazier L, Kopala L: Psychosocial rehabilitation early after the onset of psychosis. Psychiatric Services 49:1135–1137, 1998Google Scholar

7. Harding CM, Brooks GW, Asolaga TSJS, et al: The Vermont Longitudinal Study of persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 144:718–726, 1987Google Scholar

8. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser, K, et al: Recovery from severe mental illness: an intrapersonal and functional outcome definition. International Review of Psychiatry 14:318–326, 2002Google Scholar

9. Jacobson N, Greenley D: What is recovery? A conceptual model and explication. Psychiatric Services 54:482–485, 2001Google Scholar

10. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mead S, et al: Recovery-oriented psychopharmacology: redefining the goals of antipsychotic treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 61:22–29, 2000Google Scholar

11. TorreyWC, WyzikP: The recovery vision as a service improvement guide for community mental health center providers. Community Mental Health Journal 36:209–216, 2000Google Scholar

12. Mead S, Copeland ME: What recovery means to us: consumers' perspectives. Community Mental Health Journal 36:315–328, 2000Google Scholar

13. Anthony WA: Recovery from mental illness: the guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990's. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:11–23, 1993Google Scholar

14. Spaniol L, Koehler M, Hutchinson D: Recovery Workbook: Practical Coping and Empowerment Strategies for People With Psychiatric Disability. Boston, Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University, 1994Google Scholar

15. Copeland ME: Wellness Recovery Action Plan. Brattleboro, Vt, Peach Press, 1997Google Scholar

16. Bullock WA, Ensing DS, Alloy V, et al: Consumer leadership education: evaluation of a program to promote recovery in persons with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:3–12, 2000Google Scholar

17. Mueser KT, Meyer PS, Penn DL, et al: The Illness Management and Recovery Program: rationale, development, and preliminary findings. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32(suppl 1):S32–S43, 2006Google Scholar

18. Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S: A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatric Services 58:1461–1466, 2007Google Scholar

19. Ridgeway P: Restorying psychiatric disability: learning from first person narratives. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 24:335–343, 2001Google Scholar

20. Ralph RO: Review of the recovery literature: a synthesis of a sample of recovery literature. Alexandria, Va, National Association for State Mental Health Program Directors, National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, 2000Google Scholar

21. Davidson L, Strauss J: Beyond the biopsychosocial model: integrating disorder, health and recovery. Psychiatry 38:44–55, 1995Google Scholar

22. Cook JA, Copeland ME, Hamilton MM, et al: Initial outcomes of a mental illness self-management program based on Wellness Recovery Action Planning. Psychiatric Services 60:246–249, 2009Google Scholar

23. Resnick SG, Fontana A, Lehman AF, et al: An empirical conceptualization of the recovery orientation. Schizophrenia Research 75:119–128, 2005Google Scholar

24. Young A, Chinman M, Forquer S, et al: Use of a consumer-led intervention to improve provider competencies. Psychiatric Services 56:967–975, 2005Google Scholar

25. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, US Public Health Service, 1999Google Scholar

26. Herth K: Development and refinement of an instrument to measure hope. Scholarly Inquiry for Nursing Practice 5:39–51, 1991Google Scholar

27. Yanos PT, Primavera LH, Knight EL: Consumer-run service participation, recovery of social functioning, and the mediating role of psychological factors. Psychiatric Services 52:493–500, 2001Google Scholar

28. Corrigan PW, Giffort D, Rashid F, et al: Recovery as a psychological construct. Community Mental Health Journal 35:231–239, 1999Google Scholar

29. Littrell KH, Herth KA, Hinte LE: The experience of hope in adults with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 19:61–65, 1996Google Scholar

30. Herth K: Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 17:1251–1259, 1992Google Scholar

31. Rogers ES, Chamberlain J, Ellison ML, et al: A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatric Services 48: 1042–1047, 1997Google Scholar

32. Wowra SA, McCarter M: Validation of the Empowerment Scale with an outpatient mental health population. Psychiatric Services 50:959–961, 1999Google Scholar

33. Corrigan PW, Salyer M, Ralph RO, et al: Examining the factor structure of the Recovery Assessment Scale. Schizophrenia Bulletin 30:1035–1041, 2004Google Scholar

34. McNaught M, Caputi P, Oades LG, et al: Testing the validity of the RAS using an Australian sample. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 41:450–457, 2007Google Scholar

35. Anderson J, Ferrans, C: The quality of life of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 186:356–367, 2006Google Scholar

36. Gordon S, Ellis P, Haggerty C, et al: Preliminary Work Towards the Development of a Self-Assessed Measure of Consumer Outcome. Auckland, New Zealand, Health Research Council of New Zealand, 2004Google Scholar

37. Ferrans CE, Powers MJ: Quality of Life Index: development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science 8:15–24, 1985Google Scholar

38. Tabachnik BG, Fidell LS: Using Multivariate Statistics, 4th ed. Needham Heights, Mass, Allyn and Bacon, 2001Google Scholar

39. Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum, 1998Google Scholar

40. Ralph RO, Kidder K, Phillips D (eds): Can We Measure Recovery? A Compendium of Recovery and Recovery-Related Instruments. Cambridge, Mass, Evaluation Center at Human Services Research Institute, 2000Google Scholar

41. Bellack A: The scientific and consumer models of recovery in schizophrenia: concordance, contrasts and implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32:432–442, 2006Google Scholar

42. Krupa T, Eastabrook S, Hern L, et al: How do people who receive assertive community treatment experience this service? Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal 29:18–24, 2005Google Scholar

43. Results From the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2007Google Scholar