Client-Case Manager Racial Matching in a Program for Homeless Persons With Serious Mental Illness

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study evaluated the relationship between client-case manager racial matching and both service use and clinical outcomes in a case management program for homeless persons with serious mental illness. METHODS: The study focused on 1,785 clients from the first cohorts that entered the Center for Mental Health Services' Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program, a five-year demonstration program for homeless persons with mental illness established at 18 sites between 1994 and 1996. A series of two-way analyses of variance was used to assess the effect of client and case manager race and their interaction on changes in outcomes and service use over a 12-month period. RESULTS: Although African Americans had more severe problems on several measures and higher levels of service use at baseline, no differences in service use at 12 months or in the changes in client outcomes as measured by nine variables were associated with the different pairings of African-American and white clients and case managers. White clients had a greater reduction in psychotic symptoms than did African-American clients, regardless of client- case manager racial pairing. No differences were found between white and African-American clients on the amount of services received over time. CONCLUSIONS: This study found virtually no evidence of a relationship between client race, case manager race, or client-case manager racial matching on either outcomes or service use.

Previous studies have documented disparities in use of general medical services between whites and minority groups, especially African Americans. For example, compared with whites, African Americans have been reported to receive less adequate cancer-related pain relief (1), inferior care for prostate cancer (2), and less sophisticated services for cardiovascular health problems (3,4,5,6).

Some empirical studies have shown that ethnic minority groups do not receive the same types or amounts of mental health services as whites. Concerns have been raised that this discrepancy may reflect poorer treatment and result in poorer outcomes (7). For example, studies of large groups of insured, nonpoor individuals have shown that African Americans have lower probabilities of using services and lower amounts of service use than whites (8,9,10).

A large study of poor clients at a Washington State mental health clinic found that, compared with white clients, African-American clients were more often assigned to inpatient than to outpatient care, had a higher dropout rate (that is, failed to return after one session), had a lower mean number of outpatient sessions, and were less likely to see a fully trained professional (11). However, a follow-up study found that the mean numbers of outpatient sessions for African-American and white clients were equivalent. After adjustment for baseline functioning, there were no differences in rates of premature termination after the development of specialized clinic services, although some other differences remained (12). Evidence from the Los Angeles County mental health system has suggested that African Americans drop out of treatment more frequently than members of other racial groups, use fewer sessions, and have worse outcomes (7).

Several related studies have used outcomes monitoring data from the Department of Veterans Affairs to examine outcomes across racial groups. A study of more than 5,000 veterans in outpatient treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) found that white veterans had more outpatient sessions, more regular attendance, and greater commitment to treatment than African-American veterans (13). In contrast, little evidence of differences has been found in program participation or outcomes between African-American and white clients in programs for homeless veterans with mental illness or addictive disorders (14,15,16). In addition, Rosenheck and Fontana (17) found no differences in outcome or service use between racial groups in an intensive multisite outcome study involving more than 500 outpatients with PTSD.

Two studies have assessed the effects of clinician-client racial pairings on service use and outcomes (7,13). In both studies, researchers hypothesized that homogeneous client-provider matching on racial or ethnocultural characteristics would lead to improved participation and outcomes because matched clinicians have a superior understanding of clients' experiences and cultural backgrounds. Ethnically similar clinicians, it has been suggested, would be better able to assess clients' needs and would be less likely to endorse ethnic stereotypes that would hinder therapy (18). Although racial matching does not guarantee similarity in all aspects of cultural style, this approach is presumed to better address the issue of cross-racial interpersonal understanding (19).

The first study assessed clients in the Los Angeles County mental health system and found that concordant racial matching reduced rates of early termination for Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and whites, but not for African Americans (7). Although client-clinician racial matching predicted more sessions for all racial groups, it predicted improved outcomes—based on Global Assessment Scale (GAS) scores—only for Mexican Americans. The second study assessed veterans in a national outpatient PTSD treatment program and found that African-American clients who were treated by white clinicians were more likely to drop out after one session and before three months than white clients treated by white clinicians (13).

The assessment of the effects on outcomes of different clinician-client racial pairings in these two studies represents a methodological advance. However, the studies are still limited by their reliance on clinicians' reports (13) or the use of a single GAS score (7) as the only outcome measure.

Although several studies have compared outcomes across racial groups of homeless veterans, we are not aware of any studies of client-clinician ethnic matching in case management programs for homeless persons or in any other intensively studied long-term mental health program. Outreach and case management services have been empirically linked to improved outcomes for this population (20,21,22), but the impact of clinician-client racial matching in such an intensive treatment context has not been examined.

The goal of the study reported here was to assess the relationship between clinician-client racial matching for African Americans and whites and the utilization and outcomes of clinical case management services delivered through the Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) program of the Center for Mental Health Services. Although this study built on methods developed by Rosenheck and others (13) and Sue and associates (7), it was the first study of this program to have access to a rich array of outcome measures in a large client group. Using data collected from clients participating in the first two years of ACCESS, we compared both process and outcome variables among African-American and white clients who were treated by both African-American and white case managers.

Methods

The ACCESS program

The ACCESS program was initiated in 1994 by the Center for Mental Health Services to evaluate methods of increasing service systems integration and to assess the effects of these methods on clinical outcomes and quality of life of homeless people with serious mental illness (23). ACCESS is a five-year demonstration program that provides outreach and intensive case management to about 100 homeless people with severe mental illnesses each year at each of 18 sites in 15 U.S. cities.

Aspects of ACCESS case management services, which closely resemble assertive community treatment services, include assertive engagement, high intensity of service, small caseloads, expanded hours of operation, a multidisciplinary team approach, and close collaboration with social support networks, all provided within the community. Rosenheck and associates (24) evaluated the 18 sites' fidelity to the assertive community model by using a 27-item rating scale developed by Teague and colleagues (25). The mean±SD score for the 18 sites was 3.30±.24 on a scale from 1, low, to 5, high, which suggests a high level of fidelity to the model. The scores had limited variation across the 18 sites.

Data sources and eligibility criteria

The study was approved by the human investigations committee at each site. Participants provided written informed consent after ACCESS staff fully explained the details of the study to all eligible clients. Eligibility criteria for ACCESS case management services addressed homelessness, the presence of severe mental illness, and involvement in ongoing community treatment.

Homeless clients were those who had spent at least seven of the past 14 nights in a shelter, outdoors, or in a public or abandoned building at the time of first contact with ACCESS staff. A screening algorithm developed for a previous outreach demonstration project for homeless people with severe mental illness (26) was used to determine the presence of severe mental illness. Self-report scales were used to assess symptoms of depression, psychosis, and mania as well as functional status, and a series of structured interviewer observations was used to assess overtly psychotic behaviors such as delusions, agitation, and incoherence (27). The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (28) was used as a standard for validating this algorithm, which correctly identified 91 percent of persons with axis I non-substance-use psychiatric disorders (25). Eligible clients who agreed to participate in the ACCESS demonstration and gave informed consent completed a comprehensive baseline interview.

The structured baseline interview documented sociodemographic characteristics, housing status, substance use, length of time homeless, physical health status, levels of social support, employment, income, criminal involvement, quality of life, and recent victimization experiences. At three and 12 months after baseline, clients completed follow-up forms that repeated these measures. Trained interviewers who were not involved in the delivery of clinical services administered both the eligibility screening and baseline interviews.

Measures

Dependent variables. We evaluated several aspects of clinical, social, and occupational functioning. Depression was measured by the sum of five dichotomous items based on the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) (29) that indicated the presence of depression in the past month (Cronbach's alpha=.87). Client-reported symptoms of psychosis were measured by the sum of ten items indicating the presence of psychotic symptoms in the past month (Cronbach's alpha=.85). General psychological problems were evaluated with a composite measure consisting of 11 items from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (30) (Cronbach's alpha=.82). Alcohol problems were evaluated with a composite measure made up of six items from the ASI (Cronbach's alpha=.79). Drug problems were evaluated with a composite measure made up of 11 items from the ASI (Cronbach's alpha=.71). Overall quality of life was measured with a one-item rating from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted (31).

Homelessness was measured by the number of days in the past 60 the subject was literally homeless (intraclass correlation=.76). Level of social support was measured by the number of types of people the client could count on for a loan, a ride to an appointment, or help with an emotional crisis (32). The number of days of paid employment within the past 30 was determined. The reliability and validity of the DIS, the ASI, and the measures of quality of life and social support have been previously established (29,30,31,32). The measures of homelessness and employment have been used successfully in other studies (15,16).

We also assessed several types of service utilization within the past 60 days (15,24), including use of psychiatric outpatient services, measured as the number of days that clients reported receiving assistance for a psychological problem from a counselor, a case manager, any other type of outpatient personnel, or personnel at a day hospital or day treatment center; medical-surgical outpatient services, measured as the number of days that clients reported receiving care from a doctor, nurse, mobile van, shelter, dentist, or any other outpatient medical staff; substance abuse outpatient services, measured as the number of days that clients reported receiving care from a doctor, nurse, addictions counselor, case manager, or any other type of outpatient staff for an alcohol or other drug problem; employment services, measured as the number of days that clients reported receiving job training or assistance with a job search; and emergency services, measured as the number of days that clients reported receiving acute psychiatric care.

Independent variables. The two primary independent variables were the race of the ACCESS client (white or African American) and the race of the case manager (white or African American). Racial identification was based on self-reports. Data for clients who were neither white nor African American and who were treated by case managers who were neither white nor African American were excluded from these analyses.

Analyses

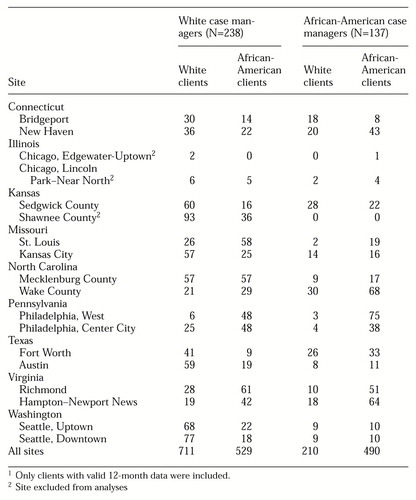

This study used data from the 15 sites that had at least ten clients served by an African-American case manager and at least ten African-American clients. All 18 sites had adequate numbers of African-American clients. Three sites were excluded because both white and African-American case managers served very small numbers of clients or because no clients were served by African-American case managers. Table 1 shows the numbers of white and African-American clients who were served by white and African-American case managers at the 18 ACCESS sites during the first two cohorts of the study and who had valid data.

Chi square analyses were used to assess the likelihood that white and African-American clients at each of the 15 sites in the study were assigned to same-race clinicians. The results showed that clients were significantly more likely to be assigned to same-race clinicians at four sites; chi square results ranged from 8.64 to 16.44 (df=1) and p values ranged from <.001 to .003. However, discussions with site coordinators and staff indicated that although race was sometimes a factor in case assignments, most assignments were made on the basis of current openings in a case manager's caseload, previous contact between a case manager and a client during the initial outreach phase, or a match between a case manager's expertise and a client's specific problems.

The analysis proceeded in several stages. First we identified baseline characteristics that differed across racial groups of clients and case managers. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to evaluate the relationship of case manager race (white or African American), client race (white or African American), and their interaction to the baseline measures of sociodemographic characteristics, clinical status, and service use. Variables for which significant differences in main effects or interactions were observed were then included as covariates in subsequent analyses of change over time.

Change was measured for all outcomes by subtracting baseline values from 12-month-outcome values. We then assessed the effect of client and case manager race on changes in outcomes and service use with another series of two-way ANOVAs that used the same main effect and interaction terms. Variables for which significant differences were observed in the baseline ANOVAs were used as covariates in each analysis along with the baseline value of the dependent variable. All effects were evaluated at the Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of .004 (.05/14 dependent variables). In addition, 14 dichotomous variables that represented the 15 sites (N [number of sites]-1=14) were included to adjust for differences in results across sites. SPSS for Windows, version 9.0, statistical software was used for all analyses.

Results

Program entry and follow-up

During the first two cohorts of the program at the 15 sites included in the study (May 1994 to July 1996), 2,398 clients gave informed consent to participate and completed baseline assessments. A total of 1,791 clients (74.7 percent) met inclusion criteria—that is, both clients and case managers were either African American or white—and completed the final interview at 12 months, between May 1995 and July 1997. Two factors significantly predicted inclusion and successful follow-up at 12 months: being African American (Wald χ2= 60.84, df=1, p<.001) and having more social support at baseline (Wald χ2= 10.62, df=1, p<.001).

Study group characteristics

The mean±SD age of the 1,791 clients in the study group was 38.4±9.4 years, and 63.7 percent (N=1,141) were male. A total of 53.1 percent (N=951) were African American, and 46.9 percent (N=840) were white. The African-American clients were younger than the white clients (mean±SD ages of 37.80±12.76 and 39.34±8.75 years; t=3.56, df=1,744, p<.001) but were no more likely to be male or female.

The mean±SD age of the 375 case managers who treated the clients in the study group was 37±10.3 years old; 40.6 percent (N=152) were male. A total of 36.4 percent (N=137) were African American, and 63.6 percent (N=238) were white. The African-American case managers were older than the white case managers (mean±SD ages of 38.67±12.76 and 35.60±8.75 years) but were no more likely to be male or female. Caseload sizes ranged from three to 86, with a mean±SD caseload of 12.9±14.1.

At 12 months, clients stated that they had a mean±SD of 4.79±8.09 contacts with their case managers in the past 60 days. This number of contacts was more than four times that with other treatment providers on the ACCESS team, including psychiatrists (1.22±1.97 contacts) and therapists, defined as "someone other than the case manager or psychiatrist" (1.02±4.25 contacts).

All clients received a diagnosis of at least one axis I disorder. The frequencies of the nonmutually exclusive diagnoses were major depression (50 percent, N=896), schizophrenia (35 percent, N=627), other psychoses (33 percent, N=591), personality disorder (23 percent, N= 412), anxiety disorder (20 percent, N=358), and bipolar disorder (20 percent, N=377). Sixty-six percent of the clients (N=1,182) received a clinical diagnosis of at least one psychotic disorder—schizophrenia, other psychoses, or bipolar disorder. The clients' mean±SD score on the depression measure was 3.3±1.9 of a possible 5, the mean±SD psychosis score was 11.9±9.4 of a possible 40, and the mean±SD level of psychosis observed by the interviewer was 11± 8.7 of a possible 52. For all measures, higher scores indicated more severe symptoms.

In addition to psychiatric difficulties, alcohol abuse disorders were diagnosed for 44 percent of the clients (N=788) and drug abuse disorders for 38 percent (N=681). Clients had been intoxicated a mean±SD of 2.2±6 days per month and had used illegal drugs 3.6±10.4 days per month.

The mean±SD level of social support (the number of types of people who would help the client with a loan, ride, or emotional crisis) was low, 2.1±4.8 of a possible 18. At baseline, clients had been literally homeless a mean±SD of 39.8±20.8 days in the past 60 days, worked a mean of 1.9±5.1 days of the past 30 days, and reported a mean monthly income of $308.20±$330.75.

Client outcome results

ANOVAs yielded several significant effects at baseline. Compared with white clients, African-American clients reported more psychological problems (mean±SD=.54±.25 versus .52±.24 problems), alcohol problems (.17±.23 versus .14±.21), drug problems (.09±.13 versus .05±.10), and symptoms of psychosis (13.08±9.35 versus 9.18±8.60 symptoms). However African-American clients reported a paradoxically higher quality of life (mean±SD score=1.98±7.10 versus 1.81±7.07). These significant variables were included as covariates in the subsequent analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs). No differences were associated with case manager race.

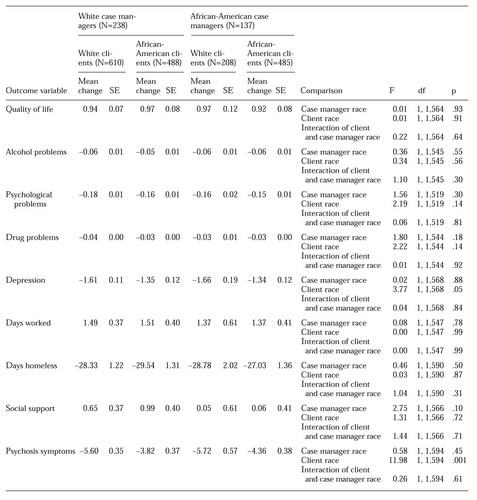

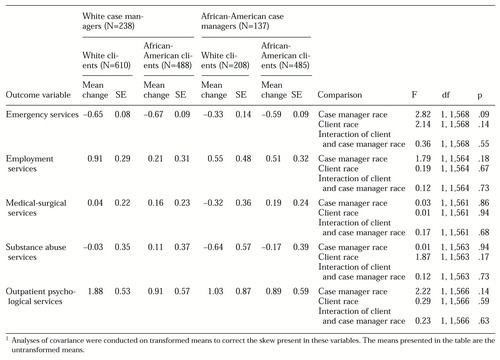

The series of ANCOVAs addressing change in client outcome variables and service use between baseline and 12-month follow-up yielded only one significant effect, a significant difference between client racial groups in change in symptoms of psychosis (F=11.98, df=1, 1,594, p=.001). This result remained significant even after the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was made (.05/14= .004). Regardless of case manager race, white clients had a greater reduction in psychotic symptoms over the 12-month period (mean±SE change=-5.66±.34) than did African-American clients (-4.09± .27). No significant main effects or interaction effects were found for changes in the service use variables (see Table 2 and Table 3 for mean change scores). Thus there were no significant relationships between client and case manager racial matching and any outcome variable.

Discussion

This study is the first of which we are aware to have assessed the effects of different racial pairings of case managers and clients in an intensive case management program. The advantages of this study included the large study group and the availability of long-term outcome data on multiple, objective measures of clients' outcomes.

At baseline, African-American clients had more severe problems on several measures as well as higher levels of service use. However, the amount of clinical improvement and service use did not differ among the different pairings of African-American and white clients and case managers, nor were there any differences related to the race of the case manager. The one difference in outcomes between African-American and white clients, regardless of the race of the case manager, was that whites had a greater reduction in psychotic symptoms during the 12-month period than did African Americans. White and African-American clients did not differ in the amount of services received. Clients in each group improved on all outcome variables to virtually same degree over the 12-month period.

The lack of significant differences in the 14 analyses examining the interaction of client and case manager race (even without the Bonferroni adjustment) suggests that case managers can treat homeless mentally ill clients of a different race as effectively as they can treat clients of their own race. It is possible that mental health personnel who choose to work with homeless mentally ill clients—a predominately minority population—are less likely than other professionals to harbor negative racial biases toward their clients. It is also possible that work on an integrated treatment team such as the typical ACCESS team, in which each client may work with several case managers, attenuates the effect of racial pairing.

Another possibility is that for this population, culturally relevant services can be provided by a member of a different racial or ethnic group and that what makes the services culturally relevant goes beyond a simple racial pairing of client and case manager. Homeless mentally ill clients may be more concerned with receiving practical assistance—for example, obtaining stable housing, food, entitlements, and mental health services—than with the race of their case manager. Therefore, simple access to case management services may be a more important factor in client improvement for this population than the race of the case manager.

Our negative findings are consistent with those of many previous studies (12,14,15,16,17) but differ from research that has documented the differential impact of racial factors on participation and client outcomes (7,11,13). Differences in methods across studies—for example, use of a single outcome measure and clinician reports versus multiple long-term, objective measures of outcome and participation—may account for the discrepancy. Weighing the empirical evidence from many studies over time will help in reaching more definitive conclusions about the importance of racial factors in the treatment of people with serious mental illness, and more specifically those who are homeless.

Certain limitations of this study deserve comment. First, the ACCESS project was not specifically designed to assess the effects of different racial pairings between case managers and homeless mentally ill clients. Although race did not affect outcomes, other factors that were not measured in this study but that reflect subtler aspects of racial identity, such as level of acculturation, cultural knowledge, and beliefs in racial stereotypes, may have affected outcomes. Sue (19) reported a high correlation between cultural attitudes and ethnicity, but the study reported here did not ensure a match on all aspects of culture. Therefore, additional research is needed to determine the degree to which the interaction of the various cultural factors of both clinicians and clients affects outcomes and service use.

Second, although a large client group participated in the study, the study design was quasi-experimental. Thus unmeasured client characteristics could have biased the results. The variables with significant differences across racial groups at baseline were included as covariates in the subsequent analyses and were unlikely to have affected our results. Nevertheless, future studies should use random assignment to determine the differential effects of clinician and client race on outcomes and level of service use. Third, although no differences in outcomes between African Americans and whites were found, regardless of case manager race, the study did not address other racial and ethnic groups, whose experiences should be studied as well.

Conclusions

In this large-scale, long-term outcome study of the effects of client-clinician racial pairing in an intensive community-based mental health program, we found virtually no evidence of any relationship between racial factors, including client-case manager racial matching and either program participation or client outcomes.

Dr. Chinman is director of program evaluation services at the Consultation Center and assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, where Dr. Rosenheck is clinical professor of psychiatry and public health. Dr. Rosenheck is also director of the Department of Veterans Affairs Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC) in New Haven. The late Dr. Lam was associate research scientist in psychiatry at Yale University School of Medicine and associate director of NEPEC. Address correspondence to Dr. Chinman at the Consultation Center, 389 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Number of white and African-American clients served by white and African-American case managers during the first two cohorts of the ACCESS program at 18 sites, May 1994 to 19961

1 Only clients with valid 12-month data were included

|

Table 2. Least-square mean change scores for outcome variables at 12-month follow-up among white and African-American clients served by white and African-American case managers during the first two cohorts of the ACCESS program at 15 sites, May 1994 to July 1996

|

Table 3. Least-square mean change scores for service use at 12-month follow-up among white and African-American clients served by white and African-American case managers during the first two cohorts of the ACCESS program at 15 sites, May 1994 to July 19961

1 Analyses of covariance were conducted on transformed means to correct the skew present in these variablesThe means presented in the table are the untransformed means.

1. Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Baez L, et al: Pain and treatment of pain in minority patients with cancer: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Minority Outpatient Pain Study. Annals of Internal Medicine 127:813-816, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Alexander GA, Brawley OW: Prostate cancer treatment outcome in blacks and whites: a summary of the literature. Seminars in Urologic Oncology 16:232-234, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

3. Ayanian JZ, Udvarhelyi S, Gatsonis CA, et al: Racial differences in the use of revascularization procedures after coronary angiography. JAMA 269:2642-2646, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Goldberg KC, Hartz AJ, Jacobsen SJ, et al: Racial and community factors influencing coronary artery bypass graft surgery rates for all 1986 Medicare patients. JAMA 267:1473-1477, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Harris DR, Andrews R, Elixhauser A: Racial and gender differences in use of procedures for black and white hospitalized adults. Ethnicity and Disease 7:91-105, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

6. Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, et al: Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiac procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs medical system. New England Journal of Medicine 329:621-627, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Sue S, Fujino DC, Hu LT, et al: Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: a test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59:533-540, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Horgan C: The demand for ambulatory mental health services from specialty providers. Health Services Research 21:291-319, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

9. Watts CA, Scheffler RM, Jewell NP: Demand for outpatient mental health services in a heavily insured population: the case of the Blue Cross and Blue Shield Association's Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Health Services Research 21:267-289, 1986Medline, Google Scholar

10. Padgett DK, Patrick C, Burns BJ, et al: Ethnicity and the use of outpatient mental health services in a national insured population. American Journal of Public Health 84:222-226, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Sue S: Community mental health services to minority groups: some optimism, some pessimism. American Psychologist 32:616-624, 1977Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. O'Sullivan MJ, Peterson PD, Cox GB, et al: Ethnic populations: community mental health services ten years later. American Journal of Community Psychology 17:17-30, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Rosenheck R, Fontana A, Cottrol C: Effect of clinician-veteran racial pairing in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 152:555-563, 1995Link, Google Scholar

14. Leda C, Rosenheck R: Race in the treatment of homeless mentally ill veterans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 183:529-537, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Rosenheck R, Leda C, Frisman L, et al: Homeless mentally ill veterans: race, service use, and treatment outcomes. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 67:632-638, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Rosenheck R, Seibyl L: Participation and outcome in a residential treatment and work therapy program for addictive disorders: the effect of race. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1029-1034, 1998Link, Google Scholar

17. Rosenheck R, Fontana AF: Race and outcome of treatment for veterans suffering from PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress 9:343-351, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

18. Comas-Diaz L, Griffith EE: Clinical Guidelines in Cross-Cultural Mental Health. New York, Wiley, 1988Google Scholar

19. Sue S: Psychotherapeutic services for ethnic minorities: two decades of research findings. American Psychologist 43:301-308, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Blankertz, LE, Cnaan RA, White, K, et al: Outreach efforts with dually diagnosed homeless persons. Families in Society 71:387-396, 1990Crossref, Google Scholar

21. Morse G: A Review of Case Management for People Who Are Homeless: Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research. Washington, DC, National Symposium on Homelessness Research, 1998Google Scholar

22. Rog D: Engaging Homeless Persons With Mental Illness Into Treatment. Alexandria, Va, National Mental Health Association, 1988Google Scholar

23. Randolph F, Blasinsky M, Legenski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

24. Rosenheck R, Morrissey J, Lam J, et al: Service system integration, access to services, and housing outcomes in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 88:1610-1615, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Teague GB, Bond GR, Drake RE: Program fidelity in assertive community treatment: development and use of a measure. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 68:216-232, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Shern DL, Lovell AM, Tsembris S, et al: The New York City Outreach Project: serving a hard-to-reach population, in Making a Difference: Interim Status Report of the McKinney Demonstration Program for Homeless Adults With Serious Mental Illness. Rockville, Md, Center for Mental Health Services, 1994Google Scholar

27. Rosenheck R, Lam J: Homeless mentally ill clients' and providers' perceptions of service needs and clients' use of services. Psychiatric Services 48:381-386, 1997Link, Google Scholar

28. Spitzer RL, Williams JBW: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 1985Google Scholar

29. Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, et al: The National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of General Psychiatry 38:381-389, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. McClellan T, Luborsky L, Woody G, et al: An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 168:26-33, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

31. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

32. Vaux A, Athanassopulou M: Social support appraisals and network resources. Journal of Community Psychology 15:537-556, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar