Racial Differences in the Prevalence of Dementia Among Patients Admitted to Nursing Homes

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence of dementia among black and white residents on admission to nursing homes and to determine whether demographic and health characteristics known to be associated with dementia were correlated with dementia in this population. METHODS: Data from medical records and structured interviews with family members, nursing staff, and nursing home residents were gathered for 2,285 persons newly admitted to nursing homes in Maryland from 1992 to 1995. A stratified sample of 59 nursing homes was used. An expert panel of five physicians classified each resident as demented, nondemented, or indeterminate. Associations between dementia status, race, and selected characteristics were examined. RESULTS: Black residents (77 percent) were significantly more likely than white residents (57 percent) to be classified as demented. Older age was associated with dementia in both races. Less education, male gender, and a history of a cerebrovascular accident were associated with an increased prevalence of dementia among white residents only. After demographic and health characteristics associated with dementia were controlled for, black race remained independently associated with a diagnosis of dementia. CONCLUSIONS: The rate of dementia on admission to nursing homes was higher among black residents than among white residents, a finding that has implications for the delivery of care. The higher rate may be due to psychosocial factors operating differently in blacks and whites that influence the timing of admission to a nursing home.

Estimates of the prevalence of dementia in the community among people age 65 and older range from 5 to 10 percent (1,2,3). There is some evidence that blacks may have higher rates than whites, particularly for dementias other than Alzheimer's disease (1,4).

Few standardized research studies on the prevalence of dementia in nursing homes have been conducted. Until the mid-1980s, most studies of mental disorders in nursing home residents did not use standardized diagnostic criteria, so it was not possible to differentiate dementia from other forms of mental illness (5). Studies using such criteria have estimated the prevalence of dementia in nursing homes to be 42 to 78 percent (6,7,8), with estimates for new admissions as high as 67 percent (9). Of all residents with dementia in nursing homes, it is thought that 50 to 60 percent have Alzheimer's disease and 25 to 30 percent have vascular dementia (8). Up to 25 percent of cognitively impaired persons in nursing homes may have reversible conditions (8), and blacks may be overrepresented among this group (10).

In a cross-sectional study of nursing home residents, Class and colleagues (11) found that 60 percent of black residents in their sample of 103 residents had dementia. The study did not assess prevalence among whites. Stegbauer and coworkers (12) found that after they controlled for education, blacks were more likely than whites to be cognitively impaired on admission to nursing homes according to their score on the Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (13). However, blacks were no more likely than whites to be diagnosed as having dementia on the basis of chart diagnoses. Limitations of this study were the use of only one nursing home, the small number of study participants (N=134), and the lack of a reliable and valid method for diagnosing dementia.

Psychosocial factors also may affect the prevalence of dementia among blacks and whites on admission to nursing homes. It has been suggested that physically or cognitively impaired blacks are more likely to remain in the community than whites because of limited financial resources and greater psychosocial support (14,15,16,17). This trend may be even more pronounced among the oldest old, those age 85 and over (16).

Reported demographic and medical characteristics associated with the development of dementia in the general population include older age; a family history of Alzheimer's disease (16,18,19,20); vascular disease; a history of a cerebrovascular accident (19,21,22,23); diabetes (24); less education (19,25,26,27); female gender, for Alzheimer's disease (16,19); male gender, for vascular dementia (19); and possibly alcoholism (28), although alcoholism as a risk factor is controversial (18,19). Blacks may have higher rates of dementia than whites (3), particularly the types of dementia associated with alcohol use, vascular disease, and head trauma (4).

The aims of this prospective study were to examine racial differences in the prevalence of dementia among persons being admitted to nursing homes and to examine the race-specific association between dementia status and demographic and health characteristics identified in previous studies as being associated with dementia (19,24,28). To our knowledge this is the first study to use an expert panel to diagnose dementia in a large sample of new nursing home admissions that is representative of nursing home residents nationally (29).

This information is important because newly admitted black and white nursing home residents may have different requirements for nursing care and psychiatric treatment, and mismatches between mental health needs and resources may occur (8). With more than 1.4 million people over age 65 currently in nursing homes (30), a population that is expected to triple by the year 2020 (8), additional epidemiological information is needed to ensure that residents of nursing homes receive appropriate care and psychiatric treatment.

Methods

Sample

A sample of 2,285 persons newly admitted to Maryland nursing homes was identified and recruited between 1992 and 1995. Subjects were recruited from a stratified representative sample of 59 nursing homes in Maryland; stratification was by geographic region, including urban and rural areas, and by bed capacity—fewer than 50 beds, 50 to 150 beds, and more than 150 beds. All residents age 65 years and older who had not resided in a nursing home during the previous year were eligible. The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the School of Medicine of the University of Maryland in Baltimore. Written informed consent was obtained from either the subjects themselves or their family members or friends.

Of the original sample of 2,285 residents, 347 were black and 1,788 were white, for a total sample of 2,135. Of these, 1,022 (48 percent) received a diagnosis of dementia from the expert panel, 673 (32 percent) were classified as nondemented, and 440 cases (21 percent) were classified as indeterminate. For the purposes of these analyses, we included only residents in the first two groups. The indeterminate diagnosis was used when the available data were inadequate or equivocal for rendering a decision on dementia status; it was used for residents who died before a baseline assessment could be made, for those who had medical comorbidity that interfered with diagnosis, and for those with whom an interview could not be conducted or rating scales completed. For instance, in 72 percent of the indeterminate cases, an interview with the resident was not conducted, compared with 30 percent of the dementia cases and 24 percent of those who were not demented. Of the 347 black residents, 67 (19 percent) were classified as indeterminate cases, compared with 373 of the 1,788 white residents (21 percent), a difference that was not statistically different.

Of the original sample of 2,135, a group of 1,695—1,415 white residents and 280 black residents—met our criteria and served as the sample for this study.

Measures

The diagnosis of dementia was made in accordance with DSM-III-R criteria (31) by an expert panel of clinicians that included two psychiatrists, two neurologists, and a geriatrician. The panel reviewed data gathered by lay interviewers from nursing home residents' medical records, from interviews with family members or significant others, from nursing staff at the nursing home, and from direct assessment of residents. Nonphysician interviewers received one week (40 hours) of training in the administration of study measures. Cognitive, affective, and functional statuses were ascertained through the use of multiple rating scales, including the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (32), the Geriatric Depression Scale (33), the modified Blessed Dementia Scale (34), the Cornell Depression Scale (35), and the Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scale (36).

After reviewing the information, two panelists (a psychiatrist and a neurologist) independently classified each resident as having or not having dementia or as being an indeterminate case. If the two panelists disagreed on the diagnostic classification, the full panel was convened to render a diagnosis. Agreement between the panel and a geriatrician who was not on the panel and who directly assessed 100 of the residents was 76 percent (kappa=.59, SE=.06). Interrater reliability for the two panelists was 81 percent (kappa=.66, SE=.07) (30).

A diagnosis of dementia did not imply that the resident had new-onset dementia. The panel made a cross-sectional assessment and did not attempt to determine time of onset. The available data also did not allow the type or types of dementia to be specified. The methods of this study have been described in more detail elsewhere (29).

Information on age, gender, educational level, and any history of a cerebrovascular accident or alcoholism was obtained from an interview with a family member or significant other. Information on any history of hypertension and diabetes was obtained from the Minimum Data Set, which is a federally mandated functional assessment instrument that nursing homes must complete for all residents (37).

Statistical analyses

The chi square test with Yates' correction was used to test for differences between groups on categorical variables. Student's t test was used to test for differences between groups on continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to compute odds ratios to compare demented with nondemented residents within each race group. Logistic regression was also used to examine the interaction of race and the chosen variables.

Results

Entire sample

A total of 1,022 (60 percent) of the 1,695 residents assessed were diagnosed as having dementia. The mean±SD age of the 1,695 residents was 81.5±7.5 years. The mean±SD number of years of education was 10.8±3.9. Seventy-two percent (N= 1,223) were female, and 83 percent (N=1,415) were white. A total of 455 residents had a history of a cerebrovascular accident. A total of 572 (41 percent) had hypertension, 278 (20 percent) had diabetes, and 142 (9 percent) had a history of alcoholism. (The percentages are not based on 1,695 because of missing data.)

Demographic and medical characteristics

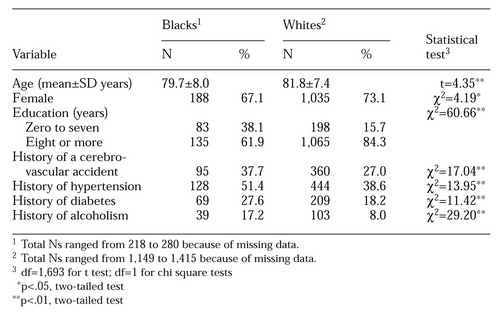

As Table 1 shows, blacks and whites in this study varied on some characteristics that have been associated with dementia in previous studies. Blacks on average were significantly younger, less educated, and more likely to be male, to have had a cerebrovascular accident, to be hypertensive, to have diabetes, and to have a history of alcoholism. On admission to the nursing homes, blacks were less likely than whites to be married; of the 280 black residents admitted, 49 (18 percent) were married, compared with 355 of the 1,415 whites (25 percent) (χ2=6.86, df=1, p<.01). Blacks were significantly more likely to have lived with someone before admission (154 blacks, or 55 percent compared with 495 whites, or 35 percent; χ2=17.1, df=1, p<.01).

Prevalence of dementia

The prevalence of dementia among blacks was 77 percent, or 215 of the 280 residents; among whites it was 57 percent, or 807 of the 1,415 residents (χ2=37.28, df=1, p<.01). Consistent with this finding, the mean±SD MMSE score of blacks was significantly lower than that of whites (14.0± 7.5 compared with 18.5±8.5; t=7.04, df=1,098, p<.01). Possible scores on the MMSE range from 0 to 30.

Blacks with and without dementia

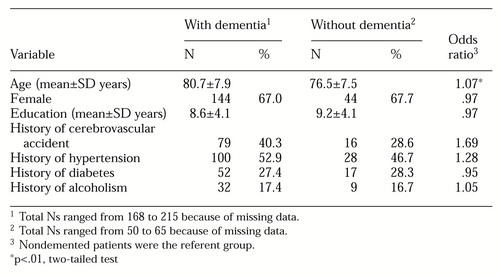

As Table 2 shows, among black residents, those with dementia were significantly older than those without dementia. The diagnosis of dementia among black residents was not significantly associated with gender or educational level or a history of a cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, diabetes, or alcoholism.

Whites with and without dementia

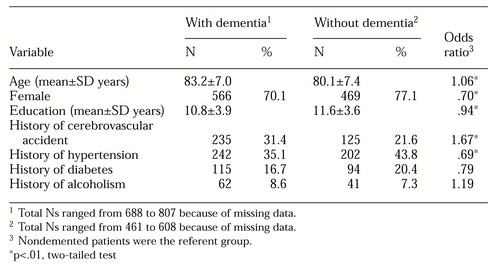

As Table 3 shows, among white residents, those with dementia were older and more likely to be male, had a lower level of education, were more likely to have had a history of a cerebrovascular accident, and were less likely to have hypertension than those without dementia. A history of diabetes or alcoholism was not associated with a diagnosis of dementia.

Interaction of variables

Using logistic regression, we did not find a significant interaction between race and any of the demographic and health variables in relation to dementia status. Lower educational level, male gender, older age, and a history of a cerebrovascular accident, diabetes, or alcoholism were not more likely to be associated with dementia among black residents than among white residents. Some indications of an association between a history of hypertension and a diagnosis of dementia that was different in direction and magnitude for the two races was noted: white residents with dementia were less likely to have hypertension, but the association was not statistically significant.

Discussion

Our study had several limitations. Clinicians did not assess the nursing home residents directly, although the use of an expert panel to diagnose dementia has been shown to have good reliability compared with direct clinical assessment (29). Also, the lower educational level of black residents overall may have resulted in lower mean MMSE scores irrespective of cognitive impairment, possibly leading to an overdiagnosis of dementia among black residents by the expert panel.

It is also important to note that the amount of data available for each patient varied. Allowing for indeterminate cases likely affected the prevalence of dementia found in both groups, but there was no significant difference between whites and blacks in the percentage of cases classified as indeterminate. Finally, the relatively small sample size of blacks may have led to a diminished power to detect significant differences in this group between those with and without dementia.

We found that among persons newly admitted to nursing homes, blacks were significantly more likely than whites to have dementia, a finding that has not been reported previously. Examining demographic and health variables that have been associated with dementia in the literature, we found that on admission to nursing homes blacks were less educated than whites, younger, more likely to be male, and more likely to have a history of a cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, diabetes, or alcoholism.

Searching for an association between these variables and dementia status in black and white residents, we found that only increasing age was significantly correlated with a diagnosis of dementia in both races. In addition, a lower education level, male gender, and a history of a cerebrovascular accident were correlated with dementia in whites only. We did not find that diabetes or alcoholism was associated with an increased prevalence of dementia in either group. Examining the interaction of race and these variables, we found that none of the interactions were associated with an increased prevalence of dementia.

Nesselroade (38) has pointed out that studying chronic care populations is difficult because of a selection effect in entry to the population, and our findings likely reflect a selection bias by race in the decision of whether to enter a nursing home. Possibly because of limited financial resources and greater psychosocial support (14,15,16,17,39), blacks may be more likely than whites to remain in the community with mild to moderate degrees of cognitive impairment, or whites may be more likely to enter nursing facilities for reasons other than cognitive impairment. Some studies have shown that elderly people who live alone are more likely to enter a nursing home (40,41). Elderly whites are more likely than elderly blacks to live with a spouse but are less likely overall to live with someone. Blacks are more likely than whites to live with children or extended family (42,43).

Results of our study support these findings. Blacks were less likely to be married on admission to nursing homes than whites but were significantly more likely to have lived with someone before admission. These findings may help explain why blacks are able to remain in the community with a greater degree of cognitive impairment than whites and why blacks on average are more likely to be cognitively impaired than whites on admission to nursing homes.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study to find racial differences in the prevalence of dementia among persons admitted to nursing homes. Features unique to this study are the large sample size, the stratified sampling of nursing homes, and the use of an expert panel to diagnose dementia.

Our findings point out the need to consider race when planning the delivery of nursing home care and when assessing nursing home residents. The higher prevalence of dementia among black residents on admission to nursing homes suggests that they are more likely to require services to address the cognitive, psychiatric, and functional impairment that accompanies dementia.

A different study is needed to determine whether blacks in the general population are more likely to have dementia than whites. If not, future studies should examine factors leading to nursing home admission in order to determine possible racial differences in admission patterns that may help explain the increased prevalence of dementia among black residents in this population.

Acknowledgments

Grant R01-AG-08211 from the National Institute on Aging provided funding for this study. Support was also received from the Baltimore Veterans Affairs Department and the Maryland Long-Term-Care Project. The authors acknowledge the contributions of other members of the epidemiology of dementia in nursing homes research group: Paul Fishman, M.D., Frank Hooper, Sc.D., Bruce Kaup, M.D., Steven Kittner, M.D., M.P.H., David Loreck, M.D., Conrad May, M.D., Joana Rosario, M.D., M.P.H., and George Taler, M.D., of the University of Maryland, Baltimore; Lynda Burton, Sc.D., of Johns Hopkins University; and Dana Hilt, M.D., of Guilford Pharmaceutical.

Dr. Weintraub is affiliated with the Norton Psychiatric Center in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Louisville School of Medicine, 200 East Chestnut Street, Louisville, Kentucky 40202 (e-mail, [email protected]). Dr. Raskin and Dr. Ruskin are with the department of psychiatry at the Baltimore Veterans Administration Medical Center and with the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Gruber-Baldini,Dr. Hebel, and Dr. Magaziner are with the department of epidemiology and preventive medicine in the division of gerontology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. Dr. Zimmerman is affiliated with the School of Social Work and the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. German is with the department of health policy and management in the School of Public Health at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

|

Table 1. Comparison of black and white persons newly admitted to rursing homes on variables associated with dementia

|

Table 2. Comparison of newly admitted black nursing home residents with and without dementia on variables associated with dementia

|

Table 3. Comparison of newly admitted white nursing home residents with and wihtout dementia on variables associated with dementia

1. Folstein M, Anthony JC, Parhad I, et al: The meaning of cognitive impairment in the elderly. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 33:228-235, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Evans DA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, et al: Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease in a community population of older persons. JAMA 262:2551-2556, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Folstein MF, Bassett SS, Anthony JC, et al: Dementia: case ascertainment in a community survey. Journal of Gerontology 46:132-138, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Baker FM: Dementing illness in African American populations: evaluation and management for the primary physician. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 24:73-91, 1991Google Scholar

5. Borson S, Liptzin B, Nininger J, et al: Nursing homes and the mentally ill elderly, in A Report of the Task Force on Nursing Homes and the Mentally Ill Elderly. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1989Google Scholar

6. Rovner BW, Kafonek S, Filipp L, et al: Prevalence of mental illness in a community nursing home. American Journal of Psychiatry 143:1446-1449, 1986Link, Google Scholar

7. Chandler JD, Chandler JE: The prevalence of neuropsychiatric disorders in a nursing home population. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 1:71-76, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Streim JE, Oslin D, Katz IR, et al: Lessons from geriatric psychiatry in the long-term care setting. Psychiatric Quarterly 68:281-307, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. German PS, Rovner BW, Burton LC, et al: The role of mental morbidity in the nursing home experience. Gerontologist 32:152-158, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Baker FM, Velli SA, Friedman J, et al: Screening tests for depression in older black and white patients. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 3:43-51, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Class CA, Unverzagt FW, Gao S, et al: Psychiatric disorders in African American nursing home residents. American Journal of Psychiatry 153:677-681, 1996Link, Google Scholar

12. Stegbauer CC, Engle VF, Graney MJ: Admission health status differences of black and white indigent nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 43:1103-1106, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Pfeiffer E: Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 23:433-441, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Larson EB, Imai Y: An overview of dementia and ethnicity with special emphasis on the epidemiology of dementia, in Ethnicity and the Dementias. Edited by Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Washington, DC, Taylor & Francis, 1996Google Scholar

15. Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D, Lieberman M: Variations in dementia characteristics by ethnic category, ibidGoogle Scholar

16. Harper MS, Alexander CD: Profile of the black elderly, in Minority Aging. Pub HRS-P-DV 90-4. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1990Google Scholar

17. Silverstein M, Waite LJ: Are blacks more likely than whites to receive and provide social support in middle and old age? Yes, no, and maybe so. Journal of Gerontology 48:S212-S222, 1993Google Scholar

18. Baker FM: Issues in assessing dementia in African American elders, in Ethnicity and the Dementias. Edited by Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Washington, DC, Taylor & Francis, 1996Google Scholar

19. Van Duijn CM: Epidemiology of the dementias: recent developments and new approaches. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 60:478-488, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

20. Van Duijn CM, Stijnen T, Hofman A: Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: overview of the EURODEM collaborative reanalysis of case-control studies. International Journal of Epidemiology 20:S4-S11, 1991Google Scholar

21. Hebert R, Brayne C: Epidemiology of vascular dementia. Neuroepidemiology 14:240-257, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

22. Tatemichi TK, Paik M, Bagiella E, et al: Risk of dementia after stroke in a hospitalized cohort: results of a longitudinal study. Neurology 44:1885-1891, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Tatemichi TK, Desmond DW, Paik M, et al: Clinical determinants of dementia related to stroke. Annals of Neurology 33:568-575, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

24. Leibson CL, Rocca WA, Hanson VA, et al: Risk of dementia among persons with diabetes mellitus: a population-based cohort study. American Journal of Epidemiology 145:301-306, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

25. Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, et al: Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer's disease. JAMA 271:1004-1010, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

26. Prencipe M, Casini AR, Ferretti C, et al: Prevalence of dementia in an elderly rural population: effects of age, sex, and education. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 60:628-633, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

27. Ott A, Breteler MM, van Harskamp F, et al: Prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia: association with education. British Medical Journal 310:970-973, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

28. Carlen PL, McAndrews MP, Weiss RT, et al: Alcohol-related dementia in the institutionalized elderly. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 18:1330-1334, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

29. Magaziner J, Zimmerman SI, German PS, et al: Ascertaining dementia by expert panel in epidemiological studies of nursing home residents. Annals of Epidemiology 6:431-437, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

30. Dey AN: Characteristics of Elderly Nursing Home Residents: Data From the 1995 National Nursing Home Survey. Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics, no 289. Hyattsville, Md, National Center for Health Statistics, 1997Google Scholar

31. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1987Google Scholar

32. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR: "Mini-Mental State": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12:189-198, 1975Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

33. Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al: Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. Journal of Psychiatric Research 17:37-49, 1983Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

34. Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, Roth M: The association between quantitative measures of dementia and of senile change in cerebral gray matter. British Journal of Psychiatry 48:314-318, 1987Google Scholar

35. Alexopolous GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al: Cornell scale for depression in dementia. Biological Psychiatry 23:271-284, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

36. Wilkinson IM, Graham-White J: Psychogeriatric Dependency Rating Scales (PGDRS). British Journal of Psychiatry 137:558-565, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

37. Hawes CH, Mor V, Phillips CD: The OBRA-87 nursing home regulations and implementation of the Resident Assessment Instrument: effects on process quality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 45:977-985, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

38. Nesselroade JR: Longitudinal research with chronic care populations: some commentary. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 8:S299-S301, 1994Google Scholar

39. Manuel RC: The demography of older blacks in the United States, in The Black American Elderly: Research on Physical and Psychosocial Health. Edited by Jackson JS. New York, Springer, 1988Google Scholar

40. Wolinsky FD, Callahan CM, Fitzgerald JF, et al: The risk of nursing home placement and subsequent death among older adults. Journal of Gerontology 47:S173-S182, 1992Google Scholar

41. Steinbach U: Social networks, institutionalization, and mortality among elderly people in the United States. Journal of Gerontology 47:S183-S190, 1992Google Scholar

42. Coward RT, Lee GR, Netzer JK, et al: Racial differences in the household composition of elders by age, gender, and area of residence. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 42:205-227, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

43. Mui AC, Choi NG, Monk A: Long-Term Care and Ethnicity. Westport, Conn, Auburn House, 1998Google Scholar