Characteristics and Service Use Patterns of Nonelderly Medicare Beneficiaries With Schizophrenia

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The authors sought to describe the characteristics of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia and to assess the impact of Medicare financing on service quality by comparing service use among individuals who were enrolled only in Medicare and those who were enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. The authors hypothesized that persons who received only Medicare benefits would use proportionally fewer psychosocial services and less antipsychotic medication than individuals who were dually enrolled. METHODS: Data were drawn from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS). The study sample consisted of 257 individuals younger than age 65 who were included in the 1995 MCBS sample and who had one inpatient or two outpatient claims for schizophrenia between 1992 and 1996. The variables examined were demographic characteristics, comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, activities of daily living, instrumental activities of daily living, self-reported use of prescribed antipsychotic medication, and claims for psychosocial services. A multivariate analysis was also conducted to predict the use of antipsychotic medication from demographic and health status variables. RESULTS: Dually enrolled beneficiaries were significantly more likely to be receiving antipsychotic medication than Medicare-only beneficiaries, even when the analysis controlled for demographic characteristics, health status, and comorbidity. No significant differences were found in the use of psychosocial services. CONCLUSIONS: The findings were consistent with the hypothesis that Medicare financing, which restricts access to many mental health services, is not conducive to good community care for persons with schizophrenia.

Medicare is the second largest public payment system for mental health services in the United States (1). About 10 percent of Medicare enrollees are younger than age 65, becoming eligible for Medicare coverage through enrollment in the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program. About 25 percent of the individuals in this group qualify for SSDI because of a psychiatric disability (1,2,3), and of these, a small but significant proportion—about 1 percent—have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (4). Individuals in this subgroup are typically heavy and persistent users of services; however, little is known about the demographic characteristics or service use patterns of this population.

Interest has grown in recent years in the impact of Medicare reimbursement on the unique service needs of persons with severe mental illness (4,5,6). In a discussion of the effect of Medicare regulations on mental health services, Ettner (5) speculated that Medicare's requirement of a 50 percent copayment for outpatient psychotherapy and the lack of a medication benefit might lead to diminished use of both of these services among persons with mental illness. Similarly, Lehman (4) expressed concern about the poor fit between the acute-care services model supported by Medicare and the need for long-term community care and rehabilitation services of persons with schizophrenia.

Preliminary support for these concerns was provided in a study that compared the use of family interventions in a national sample of individuals with schizophrenia who were receiving Medicare benefits and a state sample of individuals with schizophrenia who were enrolled in a Medicaid program (6). Medicare beneficiaries were found to be significantly less likely to have received a family intervention than Medicaid beneficiaries, suggesting that Medicare's limited reimbursement plans affected service provision.

Although the study provided nationally representative data on the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the characteristics of nonelderly persons were not specifically discussed. Furthermore, the existence of an important subgroup of Medicare beneficiaries—those who are also enrolled in Medicaid—was not addressed. Finally, the use of antipsychotic medication, which is an essential component of the treatment of schizophrenia, was not examined.

In the study reported here, data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) were analyzed to assess the characteristics and service use patterns of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. The MCBS is an ongoing panel survey of about 12,000 Medicare beneficiaries that is conducted by the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) (7). The survey sample is drawn from HCFA's national Medicare enrollment file and, with the use of weights, is statistically representative of the national Medicare population.

The survey provides information about demographic and other characteristics of the individuals in the sample and, through links with Medicare claims files, allows for an analysis of their service use patterns (8).

We also examined adherence to two treatment recommendations delineated by the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (9): persons with schizophrenia who reside in the community should receive antipsychotic medication for maintenance treatment, and they should receive psychosocial services—individual or group psychotherapy and family interventions—for support and stabilization.

We also focused on an area that has not been previously investigated, namely, the differences between nonelderly persons with schizophrenia who are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid— "dually eligible" or, more accurately, "dually enrolled" individuals—and those who are enrolled only in Medicare. By comparing the service use patterns of these two groups, we hoped to gain insight into the effect of Medicare reimbursements on the provision of services to this understudied population.

Because Medicaid offers more comprehensive mental health coverage, we hypothesized that dually enrolled persons would use proportionally more psychosocial services and would be more likely to receive antipsychotic medication than individuals who were enrolled in Medicare only. As a corollary to this hypothesis, we expected to find that persons who were enrolled in Medicare and who also had supplemental private insurance—presumably offering some prescription benefit—would use more services than individuals who were enrolled in Medicare but who did not have such insurance. We also expected to find that differences in demographic characteristics, health status, and comorbidity between dually enrolled and Medicare-only individuals would not explain differences in degree of adherence to the PORT recommendations. Such a finding would support the view that current Medicare reimbursement patterns discourage the use of appropriate treatment for persons with schizophrenia.

Methods

The MCBS employs a stratified area probability design, so that each year's sample includes individuals who are continuing in the study from previous years and individuals who are added to the survey. Respondents are interviewed at four-month intervals, producing three rounds of data a year. Response rates generally exceed 85 percent.

Sample

Our sample consisted of all individuals younger than age 65 in the 1995 sample of the MCBS cost and use survey who were identified as having a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis (ICD-9-CM code 295.XX) in at least one inpatient or two outpatient Medicare claims between 1992 and 1996. Claims data were not available for eight potential study subjects who were participating in HMO-contracted Medicare, and they were not included in our sample. This identification system was derived from previous research on Medicaid claims that found good agreement between schizophrenia diagnoses identified in this way and independent diagnoses by clinicians (10). Analyses indicated that by restricting the sample to persons with two outpatient claims, 29 individuals with only one outpatient schizophrenia claim were excluded from the study.

Although we analyzed data from only the 1995 survey, we allowed for individuals who were included in that year to have received a diagnosis in another year, because schizophrenia tends to be a persistent condition. We used this approach to increase the sample size and to minimize the problem of underidentification (10,11).

Measures

Most of the information about the study participants was drawn from the 1995 cost and use survey and 1995 Medicare claims. The variables studied included gender, marital status, race, education, age, income, living situation, psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity, original reason for enrollment in Medicare, private supplemental insurance, and self-reported difficulties in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. Activities of daily living are basic self-care activities such as bathing, dressing, and eating; instrumental activities of daily living include, for example, preparing meals, doing housework, and shopping.

Information about the participants' original reason for enrollment in Medicare was drawn from the 1996 access to care survey, because these data were not available from the 1995 survey; however, data are reported only for participants from the 1995 sample who were carried over to the 1996 sample. Information about psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity was drawn from 1995 Medicare claims: participants who had a claim for alcohol or substance dependence or abuse (ICD-9-CM codes 303, 304, and 305) were listed as having comorbid substance abuse, and participants who had a claim for a major affective disorder (ICD-9-CM code 296) or neurotic disorder (ICD-9-CM code 300) were listed as having a comorbid psychiatric disorder. Previous research with Medicaid data has found claims files to be a reliable source for identifying secondary psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses (12).

Information about the use of antipsychotic medications during 1995 was drawn from self-report data in the 1995 cost and use survey. Our analyses were restricted to community residents, because data were available only for these individuals. Antipsychotic medications were identified by either chemical or commercial name from all the antipsychotic medications listed in a current handbook of psychiatric drugs (13).

The use of psychosocial services was assessed through an analysis of Medicare claims for all community residents during 1995. The fourth edition of the Physician's Current Procedure Terminology (14) was used to identify billing codes for the psychotherapeutic services studied, which included individual psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, and family interventions.

Analyses

Data were analyzed with SUDAAN to account for the stratification design of the MCBS. Weights provided by HCFA were used to compute estimates for the total Medicare population. Service use data were available only for community residents; therefore, comparisons between individuals who were enrolled in Medicare and those who were dually enrolled were conducted for this sample only. Chi square tests were used to compare the groups' demographic characteristics, psychiatric comorbidity, health status, and service use. A multivariate logistic regression analysis, controlling for demographic characteristics, comorbidity, and health status, was then conducted to predict the use of antipsychotic medication by type of enrollment.

Results

Sample characteristics

The final sample consisted of 257 individuals, of whom 82 (35 percent) were enrolled in Medicare only and 175 (65 percent) were dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. (A stratified sample and the use of weights in data analyses account for the disparity in the percentages.) A total of 180 individuals lived in the community, and 77 resided in long-term-care institutions. Of the individuals in the community sample, 71 (39 percent) were enrolled in Medicare only and 109 (61 percent) were dually enrolled. Using weights, we estimated that about 433,500 Medicare beneficiaries in the United States in 1995 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and that about 150,000 of these individuals were not dually enrolled. Not surprisingly—given the limits on Medicare payment for long-term care—most of the individuals who were living in institutions (N=66, or 87 percent) were dually enrolled.

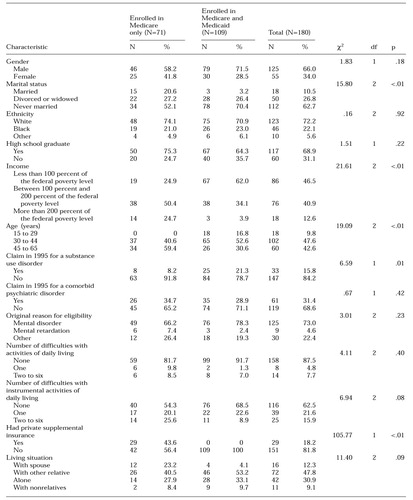

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and health status characteristics of the community sample, by type of enrollment. Using weights, we estimated that about 320,300 Medicare beneficiaries with a diagnosis of schizophrenia resided in the community in 1995 and that about 133,000 of these individuals were not dually enrolled. The demographic characteristics of the community sample in our study were similar to those of the outpatient Schizophrenia PORT sample (15), which included Medicaid, Medicare, and private insurance beneficiaries: the majority of individuals were white, had a high school education, and were unmarried.

As can be seen in Table 1, individuals who were enrolled only in Medicare differed in a number of characteristics from those who were dually enrolled. Medicare-only beneficiaries were significantly more likely to be married, to have an income above the federal poverty level, to be older, to have private supplemental insurance, and not to have filed a claim for substance abuse in 1995. Our findings were similar to those reported for the overall MCBS sample (16) in that the Medicare-only beneficiaries in our sample tended to be better educated than the dually enrolled group and more likely to be living with their spouses, although these differences were not statistically significant. However, our findings were dissimilar to the overall MCBS findings in that the dually enrolled individuals in our sample did not show significantly more impairment than the Medicare-only beneficiaries in activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living.

Service use

The use of antipsychotic medication was low for both groups of beneficiaries, especially when compared with national estimates of adherence to the PORT recommendations (4): only 55 percent of the individuals in the community sample reported receiving any antipsychotic medications during the study year, compared with 92 percent reported for the PORT study. As we predicted, individuals in the Medicare-only group were significantly less likely to be receiving antipsychotic medication than those in the dually enrolled group: 44 percent versus 63 percent (χ2=7.82, df=1, p<.01). The reported use of atypical antipsychotic medications was low for both groups: 16 percent total. Other psychotropic medications were also less commonly used—for example, 8 percent of the total sample used mood stabilizers and 25 percent used antidepressants—and their use did not differ significantly by type of enrollment.

To address the relationship between having supplemental private insurance and the use of antipsychotic medication, the Medicare-only group was subdivided into two groups. A total of 15 (34 percent) who did not have supplemental insurance were using antipsychotic medication compared with 20 (57 percent) of those who had insurance (χ2=10.55, df=2, p=.01). This finding indicates that Medicare-only beneficiaries who had only out-of-pocket means of paying for medications were the least likely to be receiving them, which is consistent with our hypothesis.

A majority of the 257 individuals in the total sample (68 percent) had Medicare claims for psychosocial services. This rate is higher than that found in the PORT sample (45 percent) (4) but is similar to the rate reported in a previous study of Medicare beneficiaries (6). The most common claim was for individual psychotherapy. Dually enrolled individuals were somewhat but not significantly more likely to have claims for group therapy, although the proportion of the sample with claims for these services was small (13 percent). Overall claims for family intervention services were rare (3 percent).

Predictors of antipsychotic medication use

Multivariate logistic regression was used to investigate the hypothesis that type of enrollment would remain a significant predictor of antipsychotic medication use even when the analysis controlled for relevant demographic, comorbidity, and health status variables. The variables included in the equation were race, gender, education, age, marital status, income, original reason for enrollment, Medicaid status, substance abuse, psychiatric comorbidity, and difficulties with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living. Because preliminary analyses indicated that small cell sizes led to wide confidence intervals, categories for many of the variables were collapsed to maximize statistical power.

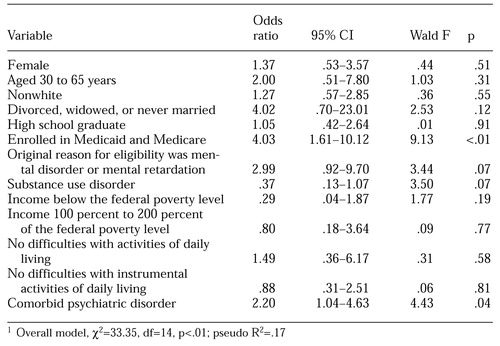

The results of the analysis are summarized in Table 2. Dual enrollment and psychiatric comorbidity were found to be significantly associated with a greater likelihood of using antipsychotic medication. The original reason for enrollment in Medicare—mental disorder or mental retardation—showed a trend toward statistical significance, as did substance abuse comorbidity, which was associated with a lower likelihood of using antipsychotic medication.

The finding of a large and significant relationship between type of enrollment and the use of antipsychotic medication even when the other variables were controlled for is consistent with the hypothesis that the use of antipsychotic medication is not explained by other predictors.

Discussion and conclusions

In our sample, nonelderly persons with schizophrenia who were covered only by Medicare were more likely than their dually enrolled counterparts to be married, to have incomes above the poverty level, and to have no indication of a comorbid substance use disorder. However, they were no less likely than their counterparts to be functionally impaired. This finding contradicts the view that Medicare beneficiaries who have schizophrenia enroll in Medicaid because they are more severely disabled; rather, it suggests that low income and lack of family resources may be more likely reasons for enrolling in Medicaid.

Findings from our analyses are generally consistent with the hypothesis that Medicare financing regulations negatively affect the delivery of services for persons with schizophrenia. As hypothesized, the use of antipsychotic medication was significantly greater among dually enrolled individuals than among those who were enrolled in Medicare only—particularly Medicare beneficiaries who had no supplemental insurance.

Multivariate analyses indicated that differences in demographic characteristics and health status did not explain the significantly greater use of antipsychotic medication among dually enrolled beneficiaries. Among individuals with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders, those who were dually enrolled were significantly less likely to use antipsychotic medication. Substance abuse was more common among dually enrolled beneficiaries, but it was associated with a lower likelihood of medication use.

Contrary to expectations, we found no significant differences between the dually enrolled group and the Medicare-only group in the use of psychosocial services. The majority of psychosocial services claims were for individual psychotherapy. Claims for other services—group psychotherapy and family interventions—tended to be more common among dually enrolled beneficiaries, but they were rare overall. Additional analyses indicated that the providers of psychosocial services for the total sample were primarily psychiatrists and that psychotherapy services were primarily provided in conjunction with medication management. This finding may reflect the impact of Medicare's differential reimbursement system for medication management, which requires a 20 percent copayment, and for psychotherapy, which requires a 50 percent copayment. The higher copayment may discourage Medicare beneficiaries from seeking services from nonpsychiatrists and may limit the range of potential services available to Medicare beneficiaries.

An alternative interpretation of our findings is that self-report data are a flawed source of information about medication use. However, the MCBS used a thorough method for ascertaining medication use, which was to ask respondents to bring the containers for all their prescribed medications to their interview. Furthermore, although this argument might explain the relatively low rate of antipsychotic medication use overall, it would not explain the large difference in use between the Medicare-only group and the dually enrolled group.

Another alternative explanation is that the use of Medicare claims to identify persons who have a diagnosis of schizophrenia leads to a large number of false positives and results in an overestimation of the number of persons who actually require services such as antipsychotic medication. However, the accumulated evidence indicates that claims data are more likely to produce false negatives than false positives (10,11). Again, this argument would not explain the large difference in use between the Medicare-only group and the dually enrolled group.

Finally, our findings could be explained if the observed relationship between the use of medication and being enrolled in Medicaid or having supplemental insurance is reciprocal, that is, individuals who feel that they need antipsychotic medication are more likely to choose to enroll in Medicaid or to have supplemental private insurance. Although this argument cannot be ruled out, if it were true one would expect that the demographic and clinical characteristics that are typically related to medication noncompliance—for example, substance abuse—would systematically predict both the use of antipsychotic medication and enrollment only in Medicare. We did not find this to be the case. This argument also ignores the complex array of external factors, such as income restrictions for Medicaid, the ability to pay for supplemental insurance, or finding employment that provides an insurance benefit, that make it implausible to regard the acquisition of additional insurance as primarily the result of personal choice or preference.

To investigate whether individuals in our sample had failed to use medication because of lack of contact with the mental health service system, additional analyses were conducted to determine the proportion of the sample that had a claim for a psychiatric visit in 1995. These analyses indicated that 78 percent of the individuals in the community sample had visited a psychiatrist in 1995 and that there was no significant difference in the number of visits between the Medicare-only and the dually enrolled groups. This finding suggests that the nonuse of antipsychotic medications was not due to lack of contact with the mental health system. A more plausible explanation is that Medicare-only beneficiaries failed to get their prescriptions filled because of the high out-of-pocket cost.

The finding that persons in the dually enrolled group reported relatively low use of antipsychotic medications—compared with an adherence rate of 92 percent reported in the PORT findings—is more difficult to interpret. It may be that enrollment in Medicare is associated with the use of fewer services even when an individual is simultaneously enrolled in Medicaid. Background characteristics that may be associated with initial enrollment in Medicare because of a disability—for example, work history or better premorbid functioning—may account in part for the use of fewer services among these beneficiaries. Research comparing the characteristics and service patterns of nonelderly Medicare beneficiaries with those of Medicaid beneficiaries is needed to address this hypothesis.

Our data indicated that a significant proportion of the Medicare-only beneficiaries who were diagnosed as having schizophrenia had incomes near or below the poverty level and did not have supplemental private insurance. These individuals were likely to be at greatest risk of not using antipsychotic medication and other services that are essential in the treatment of schizophrenia. Many met income criteria for Medicaid eligibility—Medicare beneficiaries with incomes that are 120 percent or less of the federal poverty level are automatically eligible for Medicaid (17)—or were eligible for Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which leads to automatic enrollment in Medicaid in most states. These individuals may not have been aware that they were eligible for more comprehensive coverage, or they may not have actively pursued benefits because of stigma or other factors. As Estroff and colleagues (18,19) have noted in papers based on their investigation of the "pathways" to SSDI and SSI enrollment, factors such as the advocacy of family members and mental health service providers may play a more important role than symptom severity in the process of applying for such benefits.

Because of the cross-sectional nature of our investigation, we are cautious in concluding that our findings support the view that the limited mental health benefits available under Medicare are causally related to inadequate treatment for schizophrenia. However, this interpretation is consistent with findings that have emerged from better-controlled studies among Medicaid beneficiaries (20), which have demonstrated that financing incentives can have a strong impact on service use. We suggest that future investigations use prospective designs to assess the long-term impact of Medicare financing for mental health services on both treatment and patient functioning.

Acknowledgment

This study was made possible in part by a grant from the Center for Research on the Organization and Financing of Services for the Severely Mentally Ill at Rutgers University.

Dr. Yanos is an instructor in the department of psychiatry of the New Jersey Medical School's University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Newark. He and the other authors are affiliated with the Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research at Rutgers University, 30 College Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Characteristics of a community sample of nonelderly persons with schizophrenia, by enrollment in Medicare and Medicaid

|

Table 2. Results of logistic regression analysis predicting the use of antipsychotic medication among 180 nonelderly persons with schizophrenia living in the community who were enrolled in Medicare only or in Medicare and Medicaid1

1 Overall model χ2=3335, df=14, p<.01; pseudo R2=.17

1. Lave JR, Goldman HH: Medicare financing for mental health care. Health Affairs 9(1):19-30, 1990Google Scholar

2. Chirikos TN: Medicare and the Social Security Disability Insurance program. Health Affairs 14(4):244-252, 1995Google Scholar

3. Feron DT: Diagnostic trends of disabled Social Security beneficiaries, 1986-1993. Social Security Bulletin 58:15-31, 1995Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lehman AF: Quality of care in mental health: the case of schizophrenia. Health Affairs 18(5):52-65, 1999Google Scholar

5. Ettner SL: Mental health services under Medicare: the influence of economic incentives. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 4:283-286, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, et al: Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: from treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services 50:233-238, 1999Link, Google Scholar

7. Adler GS: A profile of the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey. Health Care Financing Review 15:153-163, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

8. Eppig FJ, Chulis GS: Matching MCBS and Medicare data: the best of both worlds. Health Care Financing Review 18:211-229, 1997Medline, Google Scholar

9. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Lurie N, Popkin M, Dysken M, et al: Accuracy of diagnoses of schizophrenia in Medicaid claims. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:69-71, 1992Abstract, Google Scholar

11. Larson MJ, Farrely MC, Hodgkin D, et al: Payments and use of services for mental health, alcohol, and other drug abuse disorders: estimates from Medicare, Medicaid, and private health plans, in Mental Health, United States, 1998. Edited by Manderscheid RW, Henderson MJ. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998Google Scholar

12. Walkup JT, Boyer CA, Kellerman SL: Reliability of Medicaid claims files for use in psychiatric diagnoses and service delivery. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 27:129-139, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

13. Hall DP: Handbook of Psychiatric Drugs. Laguna Hills, Calif, Current Clinical Strategies Publishing, 1997Google Scholar

14. Physician's Current Procedure Terminology, 4th ed. Chicago, American Medical Association, 1997Google Scholar

15. Rosenheck RA, Desai R, Steinwachs D, et al: Benchmarking treatment of schizophrenia: a comparison of service delivery by the national government and by state and local providers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 188:209-216, 2000Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Murray LA, Shatto AE: Dually eligible Medicare beneficiaries. Health Care Financing Review 20:131-140, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

17. Clark WD, Hulbert MM: Research issues: dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries: challenges and opportunities. Health Care Financing Review 20:1-10, 1998Medline, Google Scholar

18. Estroff SE, Patrick DL, Zimmer CR, et al: Pathways to disability income among persons with severe, persistent psychiatric disorders. Milbank Quarterly 75:495-532, 1997Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Estroff SE, Zimmer CR, Lachiotte WS, et al: "No other way to go": pathways to disability income application among persons with severe persistent mental illness, in Mental Disorder, Work Disability, and the Law. Edited by Bonnie RJ, Monahan J. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1997Google Scholar

20. Soumerai SB, McLaughlin TJ, Ross-Degnan D, et al: Effects of limiting Medicaid drug-reimbursement benefits on the use of psychotropic agents and acute mental health services by patients with schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine 331:650-655, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar