Services to Families of Adults With Schizophrenia: From Treatment Recommendations to Dissemination

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: Data from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team project were examined to determine the extent to which families of adults with schizophrenia receive services and whether training staff in the provision of family services increases service availability. METHODS: For patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, paid claims for family therapy were identified in 1991 in a nationally representative sample of Medicare data and one state's Medicaid data. In a field study in two states, 530 patients were asked about services received by their families. A quasiexperimental dissemination of a family intervention was done at nine agencies; staff at four agencies received a standard didactic presentation, and staff at five received that standard presentation paired with intensive training. RESULTS: In the representative national Medicare sample of 15,425 persons with schizophrenia, .7 percent (N=108) had an outpatient claim for family therapy. This figure was 7.1 percent in the Medicaid sample of 5,393 persons with schizophrenia in one state. Of the 530 patients in the field study who reported having contact with their families, 159 (30 percent) reported that their families had received information, advice, or support about their illness, and 40 (8 percent) responded that their families had attended an educational or support program. At the four agencies where staff received only didactic training, no changes in family services were found after one year. Three of the five agencies where staff participated in intensive training enhanced their family services. CONCLUSIONS: A minority of families of persons with schizophrenia receive information about the illness from providers. Implementation of model family interventions is possible with considerable technical assistance. A gap exists between best practices and standard practices for families of persons with schizophrenia.

The importance of families in the lives of adults with schizophrenia is well documented. Persons with schizophrenia frequently live with their families of origin or have significant family contact (1). Families of persons with schizophrenia cite their own need for education and support to cope with their family member's illness (2).

Furthermore, numerous studies support the benefits of interventions designed to meet the needs of family members. Well-designed and rigorous clinical psychoeducation programs for families reduce patient relapse rates and enhance compliance better than individual therapy alone (3). Other family education programs enhance family knowledge and well-being (4,5).

The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) has developed treatment recommendations for the care of persons with schizophrenia (6). These recommendations were derived from an extensive review of the treatment literature that emphasized methodologically rigorous studies. Recommendations cover both psychosocial and psychopharmacologic treatments, with three recommendations specifically addressing family psychosocial interventions.

The first recommendation is that patients who have ongoing contact with their families should be offered a family psychosocial intervention that spans at least nine months and that provides a combination of education about the illness, family support, crisis intervention, and training in problem-solving skills. Second, family interventions should not be restricted to patients whose families are identified as having high levels of "expressed emotion." Third, family therapies that are based on the premise that family dysfunction is the etiology of the patient's schizophrenic disorder should not be used.

These recommendations do not prescribe one specific family intervention. Rather, the first recommendation details the necessary components of an effective family psychosocial intervention. Nor do the recommendations assert that all families must participate in a family psychosocial intervention to optimize care. Families should be offered these services, but the recommendations allow for the fact that families may or may not choose to participate. Notably, other efforts to define standards for best practices, such as the American Psychiatric Association's practice guideline (7) and the expert consensus guideline series (8), recommend that families receive education and support. The factors influencing whether families would choose to participate in a particular intervention are unclear.

Little is known about the extent to which families actually receive education and support services in routine care. Previous studies have tended to focus on selected cohorts of family members, such as members of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI) and families receiving services at one or a few institutions in a single geographic area (2,3,9,10), that may yield results not generalizable to the population at large. No large-scale studies have examined penetration of family services to families in usual community settings.

This paper presents information collected by different components of the Schizophrenia PORT project on the extent to which families of persons with schizophrenia received services and on challenges to changing current practice. The combined data from different components of the PORT project permits an assessment of services to families that is more representative of persons in treatment for schizophrenia than studies previously conducted.

Methods

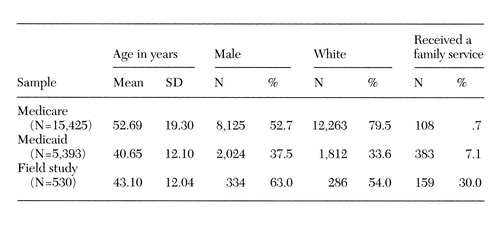

The PORT study was designed to examine patterns of treatment for persons with schizophrenia in usual care and the implications of variations in care in light of current scientific knowledge of treatment efficacy (6,11). The Schizophrenia PORT project had three interrelated components. One component examined practice variations in the public sector using administrative data collected from national insurance systems—Medicare and a state Medicaid program—which have large databases. In another component, a field study, primary data on patient outcomes and service variations in two states were collected by interviewing patients and reviewing their charts. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of subjects in the Medicare and Medicaid samples and in the field study. A final component of the PORT project attempted to disseminate treatment recommendations.

Administrative claims data

Medicare. Medicare covers disabled persons under age 65 with previous work experience and almost all Americans age 65 and over. Calendar year 1991 was the index year for selecting the study population of all persons with at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295) in any setting of care. A total of 331,617 persons met the eligibility criteria of residing in the 50 states, having a diagnosis of schizophrenia during a hospitalization or at a doctor's visit in 1991, having continuous Medicare parts A and B coverage, and surviving for all of 1991. A 5 percent random sample of the total study population was drawn, resulting in a group of 16,480 persons for analysis (6,12).

Data examined in the study reported here are from 1991 only. To allow direct comparison of whites and African Americans, our final sample included 15,425 persons; data for persons of races other than black or white were omitted from the analyses. For this study, we determined the proportion and demographic characteristics of people with a paid claim for family therapy as well as the per-person annual payment for family therapy for those who had a paid claim for family therapy.

Medicaid. Medicaid data in 1991 from a Southern state were provided by the Health Care Financing Administration. The same sample selection criterion used for Medicare was used—all persons with at least one diagnosis of schizophrenia (ICD-9-CM 295) in any setting of care. Only persons who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid for the full year were included; persons who were dually eligible for Medicare were excluded because their claims would be incomplete (12).

The final sample included 5,393 persons with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who were listed as white or African American. As in the Medicare sample, we assessed the proportion and demographic characteristics of people with a paid claim for family therapy as well as the per-person annual payment for those who had a paid claim for family therapy.

Field study

The PORT project surveyed a stratified random sample of 719 persons diagnosed as having schizophrenia in two states, one in the South and the other in the Midwest. The sampling frame provided for a random, although not necessarily epidemiologically representative, sample of persons receiving community care in public and private settings, including settings in the Veterans Affairs system. The sampling approach has been described in detail elsewhere (13).

Interviews with the subjects were conducted from December 1994 through March 1996. All subjects provided written informed consent and received $10 for their time. The interview took about 90 minutes, and subjects were asked about services to their families, the extent of their family contact, and their satisfaction with family relationships as measured by the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (14).

Dissemination

A final PORT component was community dissemination of the recommendations. The family treatment recommendations were disseminated for two reasons. First, the research on which the family psychosocial treatment recommendations were based was especially strong. Second, the results of the PORT components already described suggested that there was little implementation of family interventions in the samples examined. Consequently, we studied the relative effectiveness of two approaches to disseminating the recommendation of offering a supportive and educational family program.

The multiple-family group (15) was selected as a model of services to families, which, if offered, would be in compliance with the treatment recommendation. This model was chosen because it was found to be effective in rigorously designed research studies and had been implemented in a variety of communities in public-sector settings. Furthermore, the creators of the model had extensive experience in training and agreed to participate in this phase of our research.

Using a quasiexperimental design, we evaluated whether our dissemination approaches changed service delivery at the agency level and enhanced family participation in treatment observable at the patient level. Agency data, rather than patient or family data, are presented here. We also aimed at identifying agency factors or attitudes that impeded or facilitated successful implementation of the model.

The quasiexperimental design compared a standard educational didactic presentation with that standard presentation paired with intensive site-level training. Both interventions were presented to agency staff who work with families. The standard nonintensive intervention consisted of a lecture explaining the treatment recommendations, presenting the supporting data on the efficacy of family psychoeducation, and describing how the model intervention works. The lecture was followed by a discussion in which providers, family members, and consumers participated. The lecture and discussion were part of a full-day seminar that included other findings of the PORT projects and treatment recommendations and that was conducted in the spring of 1996 at two locations near the agencies.

The intensive site-level training consisted of a two-day program conducted in June 1996 by the originators of the standard educational presentation. In the intensive training, the trainers used books, a manual, and a video, as well as role play. The two-day program was followed by ongoing technical assistance by telephone and two subsequent on-site visits by the trainers over a one-year period.

Agency staff members at five agencies in the geographic region defined as the experimental area received the didactic presentation combined with the intensive training. Staff members at four agencies in the geographic region defined as the control area received the didactic presentation only.

Assessments to determine whether the agencies changed the services delivered to families included interviews with key informants at each agency before the intervention and one year after the intervention. A PORT investigator conducted the interview with agency staff involved with the implementation of the intervention. The 34 staff who participated in the intensive training were given pre- and posttraining tests of their knowledge and at the time of the intensive training completed a survey intended to assess their attitudes toward implementation of the family model and any obstacles encountered.

Results

Medicare

A total of .7 percent (N=108) of the nationally representative Medicare sample of 15,425 persons with schizophrenia had a paid outpatient claim for family therapy. Gender and race were not associated with the likelihood of having a paid claim for family therapy. However, most persons with such a claim were under age 65. A total of .9 percent of persons under age 65 in the sample had a paid claim for family therapy. Logistic regression analyses revealed that the older patients with schizophrenia were less likely to have a paid claim for family therapy (beta=-.03, odds ratio=.971, p<.001).

For those who had a family therapy claim, the mean±SD per-person expenditure for family therapy for the year was $153±$235. In the same Medicare sample of 15,425 persons with schizophrenia, 52 percent (N= 8,003) had a claim for individual therapy, 7.5 percent (N=1,151) had a claim for group therapy, and 23 percent (N=3,505) had a claim for psychiatric somatotherapy. A total of 65 percent of the sample (N=9,947) had at least one claim for an outpatient ambulatory service for schizophrenia.

Medicaid

A total of 7.1 percent (N=383) of the Medicaid sample of 5,393 persons with schizophrenia had a paid outpatient claim for family therapy. The probability of having a paid claim for family therapy did not differ between persons who were over 65 or under 65. When age was examined as a continuous variable, older people were less likely to receive family therapy (beta=-.02, OR=.98, p<.001). Logistic regression analysis revealed that two groups were more likely to receive family therapy—men (beta= .32, OR=1.37, p<.001) and whites (beta=.37, OR=1.45, p<.001).

For those who had a family therapy claim, the mean±SD per-person annual expenditure for family therapy was $125±$158. In the same Medicaid sample of 5,393 persons with schizophrenia, 67 percent (N=3,620) had a claim for individual therapy, 15 percent (N=789) had a claim for group therapy, and 13 percent (N= 683) had a claim for case management. A total of 4,120 persons in the sample (76 percent) had at least one claim for an outpatient ambulatory service for schizophrenia.

Field study

In assessing the extent of services received by families of patients in the PORT field study in two states, we considered only clients who were white or African American (N=650) who reported having social contacts with family members (N=530, or 82 percent). The field study provided a number of options in assessing receipt of services by families (11). The most directly relevant survey question was "Did anyone in your family receive information about your illness or your treatment or advice or support for families about how to be helpful to you?" Of the 530 patients interviewed who reported having contact with their families, 159 (30 percent) reported that their families had received such help. Forty patients (8 percent) responded affirmatively to the question "Did your family member attend any kind of educational or support program about schizophrenia and treatment?" All of the persons who responded affirmatively to the latter question responded affirmatively to the former.

In the field study sample, logistic regression analysis revealed that age was inversely related to the likelihood of receiving family education (beta= -.017, OR=.983, p<.05). Those most likely to receive a family service were whites (beta=.46, OR=1.59, p<.05) and persons with more family contact (beta=.34, OR=1.41, p<.01). Receipt of a family service was not related to type of insurance (private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid, and no insurance).

Dissemination

At the four control agencies, where staff received only the didactic training, no changes in the types and categories of services to families were found at one year postintervention. The four agencies—two hospitals, a health maintenance organization, and a community mental health center—reported that their services to families both before and after the intervention consisted of ad hoc family contact with referral to community groups.

In contrast, three of the five sites where staff members participated in the intensive training enhanced their family services. One state hospital added a component on specific problem-solving techniques to ongoing family groups. One of the three community mental health centers fully implemented the multiple-family group model. Another had partially implemented the model by the time of the one-year follow-up.

At the five intensive-training sites, the trainees at the two sites where family services did not change perceived different preintervention obstacles and attitudes than the trainees at the three sites where change occurred. Staff at sites where change was implemented rated the multiple-family group intervention as more consistent with their philosophy and mission. They also rated the methods and techniques of the model as more consistent with the general mode of providing services at their agency.

Furthermore, compared with the agencies where no change occurred, the agencies that changed their family services rated several factors as less significant obstacles to implementing the family model. These factors were lack of competent staff to carry out the intervention, low priority given to persons with severe mental illness in the agency, lack of guidance and leadership to implement the model intervention, skepticism of staff about assumptions of the model, inability to provide services to families during evenings and weekends, and confidentiality.

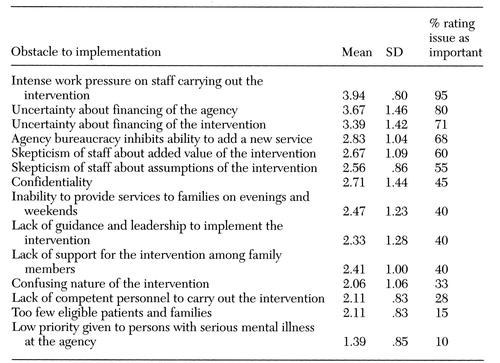

Table 2 shows the relative importance attached to each of the potential obstacles by participants in the intensive training. Issues related to lack of resources were perceived as the most important obstacle.

Discussion

Although data from each of the PORT components have significant limitations, several overall conclusions can be drawn when the different PORT components are considered together. First, even though families report they need education and support from mental health providers, only a minority of families of adults with schizophrenia receive family education from mental health providers. Medicare and Medicaid claims data for patients with this diagnosis revealed very few paid claims for family therapy, although a large proportion had paid claims for other ambulatory services for schizophrenia. Less than a third of patients interviewed in the field study who reported family contact also reported that their families received education, support, or advice.

Although the overall percentages of paid claims for family therapy for both Medicare and Medicaid were extremely low—.7 and 7.1 percent, respectively—there is an order-of-magnitude difference between them. The difference is striking and unexplained. The almost negligible percentage of Medicare claims for family therapy may reflect that program's strong orientation toward acute care and medical care, compared with Medicaid, which has typically paid for elements of psychosocial rehabilitation for patients with chronic illnesses such as schizophrenia (16,17).

Claims data are limited by billing practices and do not indicate the specific type of family therapy service for which the claim is submitted. In addition, some informal services may be delivered to families for which no claim is submitted. Unless a claim for family therapy is submitted, claims data provide no way of ascertaining whether a patient has any available family members and provide no data on family contact. It is interesting that if the percentage of patients who had family contact in the Medicaid sample was similar to that reported by patients in the field study—80 percent—the proportion of Medicaid patients with family contact who received a family therapy service would rise only from 7.1 percent to 8.9 percent. Allowing for the possibility that 20 percent of the Medicaid patients do not have family contact does not substantively increase the estimated rate of receipt of family therapy.

Interview data from the field study were limited by the patient's knowledge about the services their families received. None of the samples provide information on the possibility that families were offered services and refused them. Nevertheless, even if these limitations resulted in some underestimate of the true extent of services delivered to families, the magnitude of unmet need appears considerable.

Another consistent theme in these data is the influence of demographic factors on the receipt of family services. In the Medicaid and field study samples, whites were up to one and one half times more likely than African Americans to receive a family service. In the field study, analyses were able to control for the extent of family contact. Many possible reasons can be offered for more whites receiving a family service, including differential willingness of providers to offer this service and differential desire for a family service by race. Previous literature suggests that black families experience less subjective burden due to mental illness (17,18). The fact that this difference in receipt of family therapy by race was observed in both the Medicaid and the field study samples demands further study.

In the Medicare, Medicaid, and field study samples, families of younger people were more likely to receive a service, which may be appropriate and may reflect greater involvement of families of younger individuals with schizophrenia. However, it may also indicate that families receive less attention from professionals as persons with schizophrenia age.

Findings from the dissemination component of the study suggest that although it is difficult to change practice at an agency, doing so is possible with sufficient training and technical assistance. Traditional continuing education interventions do not produce changes in providers' behavior. An important factor in effecting change was staff members' agreement with the principles and philosophy of the model intervention. Why do innovative interventions flourish in some organizations and not in others? Current conceptualizations of the process of successful implementation of innovation have begun to emphasize organization members' perceptions of the "fit" of the innovation with their values and the organization's climate for the implementation of an innovation (19). On the preintervention survey in our study, the agencies that implemented the model had several indicators of better fit and a more favorable climate for the model. This finding suggests that future technology transfer efforts should attend to and attempt to influence organizational culture and attitudes.

Staff ratings of perceived obstacles to implementing family psychoeducation programs highlight the importance of availability of resources. Although research suggests that family psychoeducation may be cost-effective in the long run (14,20), cost savings may be realized only downstream.

The low overall rate of delivery of services to families, coupled with the difficulty of changing practice, has important implications. With the anticipated large-scale movement of Medicaid, and eventually Medicare, into managed care, oversight of services provided to people with schizophrenia must specifically include measures of family interventions. A concern with managed care is undertreatment or increased barriers to access; given the demonstrated low levels of adherence to the treatment recommendation for family services, moving from fee-for-service arrangements to managed care may exacerbate this situation to the detriment of patients.

Our analyses address only family services provided through professional medical channels. Some of the unmet needs suggested by our analyses may be met by informal sources of family services and family self-help provided by organizations such as NAMI (5). Greenberg and associates (2) suggest the importance of informal sources of help from the medical community, other family members and friends, clergy, support groups, and the media. The role of such services and the opportunities they represent must be examined so that all appropriate existing resources can be used to meet the great need for services among families of persons with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

The research reported here was conducted by the PORT investigators at the University of Maryland, Johns Hopkins University, and the Rand Corporation.

Dr. Dixon, Dr. Scott, Dr. Lehman, Dr. Postrado, and Dr. Goldman are affiliated with the Center for Mental Health Services in the department of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. Dr. Lyles is with the Health Services Research and Development Center in the department of health policy and management of Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health in Baltimore. Dr. McGlynn is with the Rand Corporation in Santa Monica, California. Send correspondence to Dr. Dixon at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, 701 West Pratt Street, Room 476, Baltimore, Maryland 21201 (e-mail, [email protected]).

|

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of thhe three samples used in the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team project and the percentage of the patients whose family received a service

|

Table 2. Ratings by field study participants in the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team project of the importance of obstacles to implementing the model intervention, a multiple-family group, at their agency1

1The number of respondents varied from 25 to 29. Ratings were made on a 5-point scale: 1, not at all important; 2, almost not at all important; 3, moderately important; 4, very important; and 5, critically important.

1. Solomon P: Families' views of service delivery: an empirical assessment, in Helping Families Cope With Mental Illness. Edited by Lefley HP, Wasow M. Newark, NJ, Harwood, 1994Google Scholar

2. Greenberg JS, Greenley JR, Kim HW: The provision of health services to families of persons with serious mental illness. Research in Community and Mental Health 8:181-204, 1995Google Scholar

3. Dixon L, Lehman AF: Family interventions for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 21:631-643, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Lam DH: Psychosocial family interventions in schizophrenia: a review of empirical studies. Psychological Medicine 21:423-441, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Pickett SA, Cook JA, Laris A: The Journey of Hope: Final Evaluation Report 1997. Chicago, University of Illinois at Chicago, National Research and Training Center on Psychiatric Disability, 1997Google Scholar

6. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: At issue: translating research into practice: the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:1-10, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Schizophrenia. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1997Google Scholar

8. Treatment of Schizophrenia Steering Committee: The Expert Consensus Guideline Series. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 57(suppl 12B):3-58, 1996Medline, Google Scholar

9. Solomon P, Marcenko M: Families of adults with severe mental illness: their satisfaction with inpatient and outpatient treatment. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal 16:121-134, 1992Crossref, Google Scholar

10. Hatfield AB, Coursey RD, Slaughter J: Family responses to behavior manifestations of mental illness. Innovations and Research 3:41-49, 1995Google Scholar

11. Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM: Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin 24:11-20, 1998Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

12. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team: Phase I-B, Secondary Data Analysis. Prepared for the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, contract 282-92-0054. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1997Google Scholar

13. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team: Phase II, Primary Data Analysis. Prepared for the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, contract 282-92-0054. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1997Google Scholar

14. Lehman AF: A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Evaluation and Program Planning 11:51-62, 1988Crossref, Google Scholar

15. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple family group and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679-687, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

16. Lave J, Goldman H: Medicare financing for mental health care. Health Affairs 9(1):19-30, 1990Google Scholar

17. Taube C, Goldman H, Salkever D: Medicaid coverage for mental illness: balancing access and costs. Health Affairs 9(1):5-18, 1990Google Scholar

18. Horwitz AV, Reinhard SC: Ethnic differences in caregiving duties and burden among parents and siblings of persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:138-150, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

19. Stueve A, Struening EL, Vine P: Psychological distress and perceived burden among caregivers of adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, in pressGoogle Scholar

20. Klein KF, Sorra JS: The challenge of innovation implementation. Academy of Management Review 21:1055-1088, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar