A Survey of Sexual Trauma Treatment Provided by VA Medical Centers

Abstract

In 1992 Congress mandated the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide treatment to veterans traumatized by sexual assault experienced during active military duty. A 1995 survey of how VA medical centers had responded to this mandate indicated that 51 percent of 136 centers had established a sexual trauma treatment team. Teams treated a mean±SD of 5.5±10 patients a week, and newly referred veterans waited a mean of 3.3±4 days for evaluation. Teams varied in the discipline mix of providers, training, organizational structure, services offered, and caseload. Medical centers without dedicated treatment teams offered nonspecialized services to sexually traumatized veterans or offered community referrals for sexual trauma treatment services.

In response to a growing awareness of sexual assault in the military, Congress included in the Veterans Health Care Act of 1992 (P.L. 102-585) the authority and priority for providing counseling and treatment for sexual trauma. Specifically, the law states that the secretary of the Department of Veterans Affairs should provide sexual trauma treatment to "overcome psychological trauma, which in the judgment of a mental health professional employed by the Department, resulted from a physical assault of a sexual nature, battery of a sexual nature, or sexual harassment which occurred while the veteran was serving on active duty."

As a result of this law, and its amendment by the Veterans Health Programs Extension Act of 1994 (P.L. 103-452), VA has funded four sexual trauma treatment centers and eight comprehensive women's health programs. In addition, VA medical centers have organized interventions ranging from establishment of treatment teams dedicated specifically to treating sexually traumatized veterans to referral of veterans to community agencies with payment for their treatment. Because the law does not outline specific guidelines for clinical protocols, team make-up, administration, or treatment procedures, implementation of the law may vary between sites.

These treatment programs are important because of the widespread occurrence of sexual assault among both civilian and military women and the profound medical and psychiatric consequences. In studies of civilian populations, up to 54 percent of women have reported sexual victimization (1,2,3), and a survey of women who served in the Persian Gulf War indicated that they were ten times more likely to be sexually assaulted than their civilian counterparts (4). The consequences of sexual assault include long-term medical and psychological problems (5,6,7,8). Providing appropriate treatment to victims of sexual trauma is essential to reducing their medical and psychiatric morbidity.

In this paper we report the results of a survey of VA's sexual trauma treatment teams, including source of referrals, team composition and training, and services offered.

Methods

Women veteran coordinators of all 162 VA medical centers were identified through the regional VA offices and were mailed a survey about available services for women veterans, including treatment for sexual trauma. Women veteran coordinators are responsible for coordinating health services for women veterans and thus were considered the most qualified persons to respond to the survey.

The survey, which was developed by the investigators and by the National Advisory Board for Treatment of Sexual Trauma in Veterans, requested information about services provided during the previous 12 months. The survey was mailed in September 1995, and data were collected by telephone by a research assistant through January 1996. To optimize the response rate, we sent an additional mailing to nonrespondents and made up to six phone calls to each nonresponding medical center. All data collection calls and follow-ups were made by the same research assistant to ensure consistency in data collection.

Key characteristics of treatment teams and medical center services were quantified through descriptive analyses. The data are reported in raw numbers, percentages, and means and standard deviations.

Results

One hundred thirty-six of the 162 women veteran coordinators answered the survey, a response rate of 84 percent. Reasons for nonparticipation were no response, eight centers; inability to contact the coordinator, eight centers; refusal, five centers; administrative difficulties, three centers; and a vacancy in the position of coordinator, two centers.

Sixty-nine of the 136 VA medical centers (51 percent) indicated that they had organized sexual trauma treatment teams. Women reporting sexual trauma while in the military were referred to the teams for treatment from a variety of VA and non-VA sources, including inpatient and outpatient medical and psychiatry services, substance abuse treatment services, and self-referral. The mean± SD number of women treated by treatment teams per week was 5.5±10, with a range of none to 58. Newly referred veterans waited a mean of 3.3±4 days (range, 0 to 30 days) for their first appointment.

A wide range of provider mix and training across treatment teams was found. Teams had a mean±SD of 5.68±3.48 members. Seventy percent of the teams had at least one psychologist, 58 percent had at least one psychiatric social worker, and 57 percent had at least one psychiatrist. Other team members were psychiatric nurses, on 41 percent of the teams; Vet Center counselors, on 33 percent; primary care physicians, on 22 percent; nonpsychiatric nurses, on 22 percent; and physician assistants, on six percent.

Sixty-eight of the teams (50 percent) had at least one member who was trained through one of two national training programs in sexual trauma treatment sponsored by VA. Many team members also received non-VA training in sexual trauma treatment. Psychologists were the discipline with the most specialized training: 83 percent had received VA training, and 63 percent had received other specialized training.

Although all treatment teams held staff team meetings, the purpose of the meetings varied widely. Many teams met for the primary purposes of administration and interdisciplinary case management; other primary functions were staffing of new patients, peer supervision, team support, and education. Teams met an average of 21.3 times a year. Teams at several facilities reported having regular meetings with staff of women's health care clinics (39 percent of the facilities), primary care practitioners (22 percent), psychiatric treatment providers (19 percent), and gynecology service staff (16 percent).

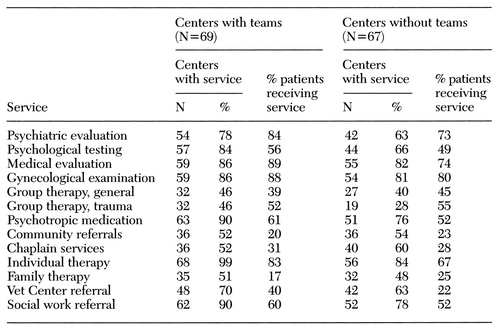

Types of mental health and medical services for victims of sexual trauma also ranged widely across VA. Table 1 lists the services available at VA medical centers with and without sexual trauma treatment teams and the mean percentages of sexually traumatized patients who used these services during the study period. For example, 54 (78 percent) of the medical centers with trauma treatment teams offered psychiatric evaluation, and a mean of 84 percent of their sexually traumatized patients used this service. Forty-two (63 percent) of the centers without teams offered psychiatric evaluation, and 73 percent of the sexually traumatized patients used this service. Only 43 of these teams (62 percent) reported using the assigned VA services code for documenting sexual trauma treatment and tracking work effort.

Discussion and conclusions

Beginning in 1992, Congress mandated treatment for all veterans reporting sexual trauma as a result of assault while on active duty. Although all VA medical centers have responded to this mandate, their approaches vary. At the time of this survey in 1995, half the centers had formed sexual trauma treatment teams, and the remaining centers either offered community referral for services or provided nonspecialized services. The teams saw an average of 5.5 patients a week, but the range was from no patients to 58. Similar wide variation was found in discipline mix on the teams, providers' training, frequency and type of team meetings, waiting time for the initial evaluation, and types of services offered. The data on services provided were not reflected in the usual VA reports, as only 62 percent of the teams used the assigned VA service code to document sexual trauma treatment.

Some caution is necessary when interpreting survey results. All the information was provided by self-report and was not verified through other sources; thus it is subject to the biases inherent in self-reported data.

The survey results suggest that future research should focus on health outcome studies, perhaps investigating the influence of various team characteristics on treatment outcome or comparing the outcomes of women veterans who received treatment from the teams with those who received community treatment. Also, because treatment by VA is mandated but specific approaches are not outlined, VA medical centers provide an ideal environment for addressing the effectiveness of different treatment approaches for sexual assault. The most efficacious and cost-effective treatments could then be exported to the civilian sector.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported in part by a developmental project award from the VA Health Services Research and Development Service through the Oklahoma City VA Medical Center (DEV 92-013) and through grant 5-R24-MH53799 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

The authors are affiliated with the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (116A), 4500 South Lancaster Road, Dallas, Texas 75216, and with the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

|

Table 1. Services available and mean percent of services received by sexually traumatized women over 12 months at 136 VA medical centers with and without sexual trauma treatment teams

1. Green BL: Psychosocial research in traumatic stress: an update. Journal of Traumatic Stress 7:341-362, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS: PTSD associated with exposure to criminal victimization in clinical and community populations, in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: DSM-IV and Beyond. Edited by Davidson JRT, Foa EB. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1993Google Scholar

3. Koss MP, Gidyez CA, Wisniewski N: The scope of rape: incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 55:162-170, 1987Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Wolfe J, Young BL, Brown PJ: Self-reported sexual assault in female Gulf War veterans. Presented at the annual meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Nov 1992Google Scholar

5. Koss MP, Goodman LA, Browne A, et al: No Safe Haven: Male Violence Against Women at Home, at Work, and in the Community. Washington, DC, American Psychological Association, 1994Google Scholar

6. Schwartz IL: Sexual violence against women: prevalence, consequences, societal, factors, and prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 7:363-373, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Resick PA: The psychological impact of rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 8:223-255, 1993Crossref, Google Scholar

8. Ellis E, Atkeson B, Calhoun K: An assessment of long term reactions to rape. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 90:263-266, 1981Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar