Improved Diagnostic Assessment of Major Depression in Psychiatric Outpatient Care in Finland

Abstract

The accuracy of diagnosis of major depression by psychiatrists, psychiatric residents, and other physicians in outpatient psychiatric care settings in Finland was examined. A total of 232 patients who visited four mental health centers in the hospital district of Satakunta during three years (1989, 1992, and 1995) were retrospectively given a diagnosis of first-episode major depression by researchers, based on chart reviews. These diagnoses were compared with those made by the evaluating clinicians. Accurate diagnosis was associated with the specialty of the physician and the location of the mental health center. Recognition of major depression significantly improved over the time period, which could be attributed to educational efforts, increasing familiarity with DSM-III-R criteria, and use of new antidepressants.

Most people with major depression are never diagnosed. The failure to recognize depressive disorders has been well established in primary care and medical settings. However, we still lack information on the ability of psychiatric practitioners to diagnose major depression (1). Psychiatrists have been shown to be either insensitive or too sensitive in diagnosing this disorder (2,3). Misconceptions about diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode have been reported (4). Little is known about the possible causes behind the failure to recognize major depression.

This study investigated how accurately major depression was assessed and diagnosed according to DSM-III-R criteria in psychiatric outpatient settings in Finland and looked for trends in the recognition of depression.

Methods

In Finland, which has an ethnically homogeneous population of 5.1 million, mental health law requires that each of the 22 hospital districts organize specialized mental health services, which are supplied free to every citizen. The hospital district provides both inpatient and outpatient psychiatric care, with mental health centers as the basic units. Mental health care is provided by a psychiatrist-managed group, consisting of psychologists, specialized nurses, and social workers.

Approximately 3 to 4 percent of the population use these services yearly, while about 70 percent have contact with primary care. The private sector plays a minor role and is concentrated only in the few larger cities.

Sample

The study was carried out in the hospital district of Satakunta on the west coast of Finland, which has a total population of more than 240,000. Satakunta was chosen because of the average sociodemographic profile of the population and because it provides average mental health services compared with some other hospital districts.

The study is based on all the patients who sought treatment for any reason at four mental health centers in the years 1989, 1992, and 1995 in Satakunta and who met DSM-III-R criteria for major depression in a retrospective evaluation. DSM-III-R was in official use in Finland from 1987 to 1995. Patients included in the study had no previously documented episodes of major depression or contact with psychiatric care and were between 18 and 64 years old. They had to have visited the mental health center at least twice during the depressive episode. A total of 232 of 1,919 patients (12.1 percent) fulfilled the study criteria.

Diagnostic evaluation

The retrospective diagnosis for the study, which was made by the first author, was based on review of clinical records and all the other documents that had been available in the actual diagnostic and therapeutic process. The documents for 1,919 patients were checked at least four times. Detailed data were collected for the 232 patients fulfilling the criteria.

Information was gathered on sociodemographic and clinical variables, target symptoms, and diagnoses made by the mental health center practitioners. A checklist of symptoms of depression from DSM-III-R was used to record whether or not the patient experienced the symptoms. The proposed diagnoses were compared with the retrospective diagnosis. Information was recorded for up to three months after the patient's first contact with the mental health center.

In addition to the diagnosis made by the first author, two experienced psychiatrists (the third and fourth authors) independently re-evaluated the documents and made diagnoses according to DSM-III-R criteria. The reliability achieved for major depression was good (kappa=.96 for the third author and kappa=.94 for the fourth).

Analysis

The data were analyzed using version 6.10 of the SAS software package. Standard statistical tests, including chi square tests and nonparametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis), and one-way analysis of variance were used. The significance level was set at .05.

Results

The 95 male patients (41 percent) and 137 female patients (59 percent) had a mean±SD age of 40.9±11.5 years at intake. Of these patients, 130 (56 percent) were married. A total of 181 patients (78 percent) were living with at least one other person. Fifty-three patients (23 percent) had completed high school, and 102 (44 percent) were manual workers. Eighty-one (35 percent) were evaluated at intake by psychiatrists, 58 (25 percent) by psychiatric residents, and 93 (40 percent) by other physicians.

The average time from the patient's first contact with the mental health center to assignment of the diagnosis was 5.9 days (median, 0; quartile range, five days). The average time from first contact to the appointment with a physician was eight days (median, 0; quartile range, eight days). Eighty-five patients (37 percent) dropped out before three months had passed, yielding a total mean follow-up time of 74.6 ±27.8 days.

Patients differed by study year on some variables, including level of education, socioeconomic status, and type of practitioner making the diagnosis. However, the variables were not significantly associated with improved diagnostic assessment during the study years.

Diagnostic assessment

The number of target symptoms documented in patients' charts significantly increased during the study (6.19 symptoms in 1989, 6.15 in 1992, and 7.19 in 1995; χ2=42.9, df=2, p<.001). In addition, the number of documented positive target symptoms required for diagnosis increased (5.50 in 1989, 5.56 in 1992, and 6.13 in 1995; χ2=21.5, df=2, p<.001).

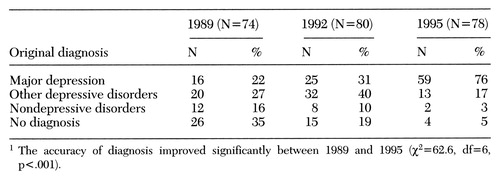

The diagnoses made by the practitioners for the 232 patients retrospectively diagnosed as having major depression are presented in Table 1. Accurate diagnosis was associated with the specialty of the physician (χ2= 18.7, df=8, p=.016). The psychiatrists had correctly recognized major depression in 53 percent (N=40) of the 75 patients they evaluated who were retrospectively diagnosed as having this disorder. The psychiatric residents had recognized it in 46 percent (N=25) of the 54 patients they evaluated who had major depression, and other physicians had recognized it in 37 percent (N=32) of their 87 patients with the disorder. Also, accurate diagnosis was independently associated with the location of the mental health center (χ2=29.8, df=12, p=.003). The other sociodemographic and treatment variables had no statistically significant association with accurate diagnosis.

Discussion and conclusions

First, the study suffered the limitations common to the retrospective method in general (5). Second, selection of patients from mental health settings probably caused some bias. Patients in such settings have been reported to have more severe symptoms than those in primary care (6). Third, we may not have recognized some cases of major depression because of limitations of documented information in the charts. Fourth, some confounding factors between the study years may not have been taken into account. However, between 1989 and 1995, DSM-III-R was in official use, and no major structural, organizational, or specific educational changes occurred in the Satakunta hospital district.

The records we evaluated did not generally reflect a systematic and comprehensive approach to diagnostic assessment. The recognition of major depression was associated with the specialty of the physician and the location of the mental health center. The few previous studies on this topic both support and do not support this association (7,8). However, comparison is difficult because of methodological differences.

Another major finding was a clear improvement in the recognition of major depression over the study period. Also, target symptoms were asked about and documented more often during the course of the study. The positive change seemed to occur between 1992 and 1995. How do we interpret this change?

First, in Finland as elsewhere, major educational efforts have been carried out to improve recognition and management of depression. These efforts were highlighted in 1994 by a national consensus panel, which gave clear guidelines for diagnosing and treating major depression. The positive effect of clinical guidelines and special education has been reported (9).

Second, during the study years, the DSM-III-R classification scheme, which has increased the reliability of diagnoses, was in official use in Finland. Our results may also reflect the time required for practitioners to fully internalize DSM-III-R concepts and use the diagnostic criteria.

Third, the rapidly increasing use of new antidepressants may also have lowered the threshold for diagnosis (10). To test this hypothesis, we will further investigate how the patients with major depression in this study were treated and with what consequences.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the Finnish Cultural Fund.

|

Table 1. Original diagnoses made by practitioners in 1989, 1992, and 1995 for 232 patients in psychiatric outpatient care in Finland who were later retrospectively diagnosed as having major depression1

1. Brugha TS: Depression undertreatment: lost cohorts, lost opportunities. Psychological Medicine 25:3-6, 1995Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

2. Spitzer RL, Skodol AE, Williams JB, et al: Supervising intake diagnosis. Archives of General Psychiatry 39:1299-1305, 1982Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

3. Schulberg HC, Saul M, McClelland M, et al: Assessing depression in primary medical and psychiatric practices. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1164-1170, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Rubinson E, Asnis GA, Harkavy JM, et al: Knowledge of the diagnostic criteria for major depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 176:480-484, 1988Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. Brugha TS, Lindsay F: Quality of mental health service care: the forgotten pathway from process to outcome. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 31:89-98, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Salokangas RKR, Poutanen O, StengÅrd E, et al: Prevalence of depression among patients seen in community health centers and community mental health centers. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 93:427-433, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

7. Andersen SM, Harthorn BM: The recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of mental disorders by primary care physicians. Medical Care 27:869-886, 1989Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Langwieler G, Linden M: Therapist individuality in the diagnosis and treatment of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 27:1-12, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Rutz W, von Knorring L, WÅlinder J: Long-term effects of an educational program for general practitioners by the Swedish Committee for the Prevention and Treatment of Depression. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 85:83-88, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

10. Sorvaniemi M, Joukamaa M, Helenius H, et al: Recognition and management of major depression in psychiatric outpatient care: a questionnaire survey. Journal of Affective Disorders 41:223-227, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar