Treatment of Major Depression Before and After Implementation of a Behavioral Health Carve-Out Plan

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: The study examined utilization, payments, and quality indicators for treatment of major depressive disorder before and after the 1993 implementation of a behavioral health care carve-out plan for Massachusetts state employees who received medical coverage through indemnity plans or preferred provider organizations. METHODS: The sample of 2,259 enrollees with claims for treatment of major depressive disorder was drawn from the group of 39,541 persons continuously enrolled in preferred provider organizations or indemnity plans for fiscal years 1992 to 1995. A subsample of 243 users of inpatient services accounted for 352 admissions. Bivariate tests were used to compare utilization and quality indicators before and after implementation of the carve-out plan. Simple comparisons of current-year dollars were used. RESULTS: The proportion of enrollees with claims for treatment of major depressive disorder increased significantly under the carve-out plan. Inpatient utilization decreased substantially, mostly due to a significantly lower average length of stay (16 days before implementation of the carve-out plan and nine days after). Net inpatient payments fell 71 percent overall, 65 percent per admission, and 40 percent per day. The unadjusted proportion of discharged patients treated for major depressive disorder who were readmitted within 15 and 30 days did not change significantly. The unadjusted proportion of cases receiving follow-up within those time frames increased significantly. CONCLUSIONS: Implementation of a behavioral health carve-out plan may be accompanied by substantial reductions in inpatient utilization and payments for treatment of major depressive disorder. Descriptive findings suggest that such reductions may not have a detrimental impact on readmission and follow-up treatment rates within 30 days. However, this analysis did not control for patient characteristics, used short follow-up periods, and did not include some relevant outcome measures.

One approach to managing mental health and substance abuse care is the behavioral health care carve-out plan, which separates benefits for such care from general medical benefits. Carve-outs generally have separate budgets, provider networks, and incentive arrangements (1). Covered services, utilization management techniques, financial risk, and other features vary depending on the particular carve-out contract.

Carve-outs have become increasingly popular in both the private and the public sector. In 1996 an estimated 56 million persons were enrolled in network-based specialty behavioral health programs (as opposed to those involving employee assistance programs or utilization review only) (2). However, not enough is known about the effects of carve-outs. The available evidence suggests that these plans tend to cut costs considerably, but their effects on utilization and quality of care are not as clear (3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, Huskamp H, unpublished manuscript, 1997). Evidence of the effects on enrollees with specific psychiatric disorders—especially within employed populations—is sparse.

Many studies of carve-outs are based on single cases, often with no control or comparison group. This approach has well-known limitations, especially its inability to determine causality. However, experimental designs are often impossible given the real-world constraints that surround major changes in health care delivery. Rather than forgo attempts to evaluate particular health system changes, including the use of carve-outs, it is preferable to use available data and contextual information to learn whatever is possible. This is especially true given that the research on carve-outs is still in an early stage.

This study focuses on utilization, payments, and quality indicators for treatment of major depressive disorder before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out plan for Massachusetts state employees. The analysis is based primarily on data about inpatient treatment. Use of disorder-specific quality indicators was not feasible given data limitations. The indicators used were readmission within 15 and 30 days and postdischarge follow-up within the same time periods. Major depressive disorder was chosen as the diagnosis of interest because it is serious, fairly common, and highly treatable.

Carve-out characteristics

The Group Insurance Commission is the agency responsible for arranging health insurance and other benefits for Massachusetts state employees and certain other public employees, retirees, and their spouses and dependents. In July 1993 the Group Insurance Commission implemented a behavioral health carve-out plan. The carve-out covered enrollees in a managed indemnity plan that continued to be offered and in a preferred-provider-organization plan initiated at the same time as the carve-out. Enrollees in health maintenance organizations were not included in the carve-out plan.

The vendor that was selected to operate the carve-out was Options Mental Health. The contract involved a modest degree of vendor risk-sharing in which the administrative fee was partly contingent on meeting a claims target (3). If actual costs were higher than the claims target, 20 percent of the excess would be subtracted from the fee. However, this risk was limited to a maximum of 20 percent of the fee. Options Mental Health also had to meet various performance targets, which did not include readmission or follow-up measures, to receive the full fee. Every failure to meet a performance goal would result in a penalty equal to 2 percent of the administrative fee. The total maximum penalty for failure to meet claims and performance goals was 23 percent of the fee. There was no contractual reward for achieving costs lower than the target or for exceeding the performance goals. Individual providers and hospitals continued to be paid on a negotiated fee-for-service and per diem basis, respectively.

The carve-out plan featured a specialty network with differential cost-sharing, limits, and utilization review procedures for in-network versus out-of-network care. For maximum coverage for all services except out-of-network outpatient care, enrollees were required to obtain precertification via a toll-free phone number. The managed indemnity plan that had previously covered mental health care required precertification only for hospitalization.

In-network carve-out benefits were more extensive than those provided by the indemnity plan, which had itself been relatively generous. The indemnity plan covered 100 percent of the cost of inpatient mental health care in general hospitals for 120 days annually, then 96 percent of the cost, or 100 percent of the cost of inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals for 60 days, then 80 percent of the cost for up to 301 days. A $150 deductible applied to care in both settings. The carve-out covered in-network inpatient mental health care at 100 percent for any hospital, with no specified day limit.

The indemnity plan covered 50 percent of the cost of outpatient care, up to $1,500 annually. In-network carve-out benefits covered 100 percent of the first four outpatient visits in a year, with a $20 copay for the fifth through the 25th visits, and a $40 copay subsequently. The carve-out covered intermediate care such as residential care and day treatment when deemed necessary, while the indemnity plan did not. Lifetime limits for both plans were $1 million, including general medical payments.

The carve-out plan covered out-of-network benefits at a lower level. Inpatient coverage was 80 percent of allowed charges in general hospitals and 80 percent of allowed charges up to 60 days annually in psychiatric hospitals. Outpatient coverage was 50 percent up to 15 visits per year. Intermediate care was covered at 80 percent. Lifetime limits were $100,000.

Methods

A sample of 2,259 enrollees with claims for treatment of major depressive disorder was drawn from 39,541 persons who were continuously enrolled in the indemnity or preferred-provider-organization general medical plans from July 1, 1991, to June 30, 1995 (fiscal years 1992 to 1995) and were under 65 years of age. For most analyses, the subsample consisted of claimants with one or more hospitalizations for which the primary diagnosis was major depressive disorder (N=243). Frequently, the unit of analysis was hospital admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder (N=352).

Data sources were eligibility files and behavioral health claims during fiscal years 1992 to 1995. These sources provided two full years of claims data before implementation of the behavioral health carve-out plan. Claims for the final quarter of fiscal year 1995 were excluded because they were clearly incomplete. To maximize the number of claimants and admissions included in the analysis, utilization and payment totals for the period after implementation of the carve-out were estimated based on 21 months of experience (using nine-month data in the last fiscal year for the yearly total). For the analyses of readmissions and follow-up treatment, in which the proportion of admissions rather than the total number is key, actual figures from the period after implementation of the carve-out were used. Both in-network and out-of-network claims under the carve-out plan were included, although they could not be differentiated for this analysis.

Behavioral health claims were defined as those that list a mental health or substance abuse disorder as the primary diagnosis. A primary diagnosis of major depressive disorder was identified based on ICD-9-CM codes 296.2 (single episode) and 296.3 (recurrent episode). For inpatient cases of major depressive disorder, the primary diagnosis was assigned by MEDSTAT software for the entire admission based on submitted claims. Admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder that occurred before and after implementation of the carve-out were identified by the admission date.

Only two admissions began during the period before implementation and continued into the postimplementation period; these two admissions were included in the preimplementation group. Any readmission to a different hospital within one day was considered a transfer, and the claims from both admissions were merged for the analysis.

Readmission and follow-up treatment rates were measured within 15 and 30 days after discharge from an admission for treatment of major depressive disorder. Readmission was defined as hospitalization for any behavioral health diagnosis. Follow-up service was defined as any eligible outpatient, alternative, partial care, or residential service (except emergency room care) that occurred after discharge and before readmission for treatment of any behavioral health diagnosis. Eligible services were defined as those for which the primary diagnosis was a mental health or substance abuse disorder, the provider type was a behavioral health or primary care provider, the place of service was not a hospital inpatient setting, and the service type and procedure codes were either psychiatric or generic medical.

Most medical specialty procedures, surgery, and laboratory tests and other tests were excluded. Emergency room care, as indicated by procedure or place codes, was also excluded as the goal of the analysis was to measure follow-up services that might reflect effective treatment planning. Missing codes on the variables listed above did not exclude an otherwise eligible visit from being counted.

Bivariate tests (chi square for nominal variables and t test for continuous variables) were used to compare utilization measures and quality indicators before and after implementation of the behavioral health carve-out plan. For payments, we used simple comparisons of actual, current-year dollars.

Results

There were 141 enrollees with any inpatient admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder during the period before implementation of the carve-out, and 102 such users during the shorter period after implementation. The two groups were similar in most sociodemographic characteristics. Mean age at initial eligibility was about 42 years for both groups.

About half of both groups were primary insured persons, approximately another third were spouses, and the rest were children or other dependents. For about three-quarters of both groups of claimants, the primary insured person was an active employee rather than a retired worker, deferred retiree, employee who was involuntarily laid off, COBRA recipient, orphan, or survivor. Two-thirds of the claimants before implementation of the carve-out and almost three-quarters of those after implementation had family coverage. The only significant difference was that women accounted for 74.5 percent of the claimants before implementation of the carve-out and 59.8 percent of those after implementation (χ2 =5.88, df=1, p<.05).

Selected utilization measures for the periods before and after implementation of the carve-out were compared. The proportion of enrollees with any claims for treatment of major depressive disorder increased 34.6 percent from .026 before the implementation to .035 after, a significant difference (χ2 =47.02, df=1, p<.001). (The proportion for the period after implementation is an estimate for the full period.) Among all enrollees with a claim for treatment of major depressive disorder, the proportion with any inpatient admissions decreased significantly from .133 before implementation of the carve-out to an estimated .085 after, a change of 36.1 percent (χ2 = 13.96, df=1, p<.001).

The average number of admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder per 1,000 enrollees per year was 2.59 before implementation of the carve-out and 2.12 after, a nonsignificant difference. The mean length of stay for treatment of major depressive disorder decreased 40.6 percent, from 15.84±12.38 days before implementation of the carve-out to 9.41±7.54 after, a significant difference (t=6.04, df=342, p<.001). The median length of admission before the carve-out was 13 days, compared with eight days after the carve-out. The mean annual number of inpatient days for treatment of major depressive disorder per 1,000 enrollees was 41.07 before implementation of the carve-out and 19.99 after, a significant decrease of 51.3 percent (t= 3.82, df=39,540, p<.001).

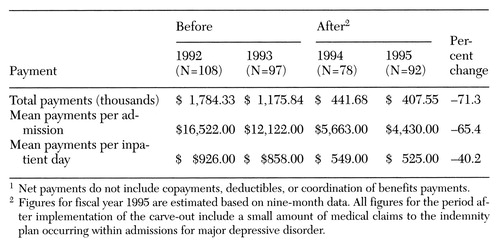

Table 1 presents yearly net payments for inpatient services for treatment of major depressive disorder. The percentage change is based on the difference between the average of the annual totals for the period before implementation of the carve-out and the average of the estimated annual totals for the period after implementation. Net payments are those made by the plan and do not include copayments, deductibles, or coordination of benefit payments.

The figures shown for the period after implementation of the carve-out include a small amount attributable to claims to the managed indemnity plan that occurred during admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder. Generally the claims were for medical (nonpsychiatric) services that were rendered during these admissions. Because such claims are included in the totals for the period before implementation of the carve-out, when the indemnity plan paid for both behavioral and general medical services, the comparison reported here is probably the fairest from the payer perspective. In any case, the claims to the indemnity plan accounted for approximately 4 percent of total net payments.

Total net payments for all admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder went down 71.3 percent after implementation of the carve-out, from $2.96 million to $849,200. Although a reduction was already taking place during the period before the carve-out, the magnitude of the drop that occurred during the first year after implementation of the carve-out was much greater.

Because part of the decrease in total expenditures was due to the smaller number of admissions after the carve-out, we also examined mean payments per admission. Net payments per admission went from an average of $14,440 before implementation of the carve-out to $4,995 after, a 65.4 percent reduction. Again, while a major reduction did occur during the period before the carve-out, a proportionately much greater decrease occurred immediately after the carve-out.

Because changes in average length of stay affect costs per admission, it is also important to look at the mean net payments per inpatient day. This amount includes all service payments for inpatient care, not only the hospital per diem rate, but hospital payments constitute the largest proportion. This figure went down 40.2 percent, from an average of $898 per day before the carve-out was implemented to $537 per day after implementation. Once again, it seems that a discrete change—a decrease—occurred after implementation of the carve-out. For all payment measures, reductions that occurred during fiscal year 1994 accounted for most of the decreases between the two periods. Further reductions during fiscal year 1995 were modest.

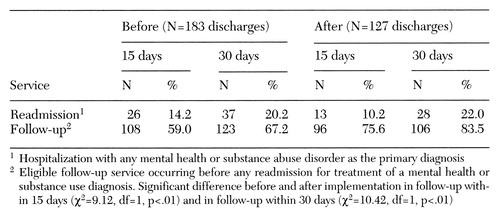

Table 2 compares readmission and follow-up rates within 15 and 30 days after discharge from treatment for major depressive disorder. During the period before the carve-out, 14.2 percent of the discharges were followed by readmission within 15 days, compared with 10.2 percent of the discharges after the carve-out, not a significant difference. Readmissions within 30 days occurred for 20.2 percent of discharges before the carve-out and for 22 percent of the discharges after, which was not a significant difference.

The proportion of cases receiving follow-up within 15 days went up significantly, from 59 percent before the carve-out to 75.6 percent after (χ2 = 9.12, df=1, p<.01). Similarly, follow-up within 30 days was more likely after the carve-out (67.2 percent before the carve-out, compared with 83.5 percent after; χ2 =10.42, df=1, p<.01).

Discussion

The findings indicate that the proportion of enrollees with claims for treatment of major depressive disorder increased significantly under the carve-out. This change might reflect an increase in access to care for persons with major depressive disorder as a primary diagnosis. On the other hand, it is possible that providers assigned more serious diagnoses when faced with tighter utilization management. This possibility could be investigated in future work by looking at patterns for coding diagnoses across all diagnostic categories.

Meanwhile, the reliance on inpatient hospital care for treatment of major depressive disorder appeared to decrease, in that the proportion of all persons with claims for such treatment who had any inpatient use decreased. The degree to which this pattern reflects a shift to outpatient care depends partly on whether "upcoding" occurred, that is, providers' assigning more serious diagnoses. At the same time, there was an overall reduction in the use of inpatient care for treatment of major depressive disorder. Admission rates did go down somewhat, though the change was not statistically significant.

The much lower level of inpatient utilization after implementation of the carve-out was largely due to the nearly 41 percent reduction in average length of inpatient stays. An examination of average length of stay by year revealed decreases from about 18 days in fiscal year 1992 to 14 days in 1993, ten days in 1994, and eight days in 1995. Thus a decrease was already occurring during the period before the carve-out, and the reduction between the periods before and after the carve-out cannot clearly be attributed to the carve-out. Still, during the period after the carve-out, average length of stay continued to fall substantially, and from a much lower base. It seems reasonable to suspect that such reductions from a lower base would be more difficult to attain.

Total payments for all admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder decreased dramatically. In most payment categories, sharper decreases occurred after implementation of the carve-out than before. The somewhat lower admission rate after the carve-out accounts for a portion of overall savings. The main factors, however, are reduced average length of stay and lower payments per day.

Because most of the inpatient service payments were to hospitals, the per-day payment results indicate that hospitals experienced a severe cut in payments. Obtaining price concessions from providers is one of the hallmarks of managed behavioral health care, so this finding is not surprising. However, the magnitude of the reduction suggests that this source of savings cannot be indefinitely tapped. At some point, hospitals will be unable to reduce costs further without detrimental effects on quality, or they will exhaust any remaining cost-shifting possibilities that postpone such deterioration. We do not know how hospitals have dealt with these cuts in terms of service provision. In this study, the lack of major reductions during the second year after implementation of the carve-out suggests that perhaps a floor had already been reached.

In the context of greatly reduced average length of stay and a more than 70 percent reduction in total net payments for inpatient care for major depressive disorder, it is interesting to note that readmission rates within 15 and 30 days did not change significantly. Increases in rapid readmission rates are sometimes feared as a potential consequence of shorter lengths of stay and, when found, tend to generate concern. The proportion of discharges receiving follow-up services within 15 and 30 days improved significantly after the carve-out. Because timely postdischarge follow-up is widely believed to be important, these findings are positive.

The findings must be viewed in the context of a number of limitations. The analysis did not control for patient characteristics. Although use of a continuously enrolled sample addressed many of the selection problems involved in comparison of the periods before and after implementation of the carve-out, differences between patients who used services during the two periods are entirely possible. In addition, the time frames for readmission and follow-up treatment are short. Future work will report on multivariate analyses of quality indicators observed over a longer time period.

Also, the case study design does not allow us to determine whether factors other than the carve-out—for instance, improvements in antidepressant medications or tighter management across all types of insurance plans—contributed to the observed changes. No comparison with managed care approaches that did not involve a carve-out arrangement was done, and similar changes could be associated with non-carve-out managed care. Lack of a comprehensive analysis of outpatient claims means that a full picture of care patterns for major depressive disorder is not available. Finally, many relevant outcome measures were not included in this study. Depression-specific clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction, and family burden are among the measures that future research might incorporate.

Conclusions

The study results suggest that implementation of a behavioral health care carve-out may be accompanied by substantial reductions in inpatient utilization and payments for treatment of major depression. Many previous studies have not examined how persons with specific diagnoses fare under carve-outs, thus leaving open the question of how particular subgroups are affected. In this case, major changes in care patterns occurred for a seriously ill group.

The readmission and follow-up results suggest that even major cuts in inpatient utilization and spending do not necessarily have a detrimental impact on those indicators. In fact, follow-up rates rose under the carve-out. These results are only descriptive, however, and need further investigation. The magnitude of changes in utilization patterns underlines the ongoing need for comprehensive and clinically informed research on how behavioral health carve-outs affect quality of care. A better understanding of the effects of carve-outs will, among other things, assist institutional purchasers of health care in making decisions about behavioral health benefits.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health predoctoral training program and by cooperative agreement 1 P50 DA10233-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The author thanks Didem Bernard for programming assistance and Tom McGuire, Ph.D., Jim Callahan, Ph.D., Bill Crown, Ph.D., Barbara Dickey, Ph.D., and Haiden Huskamp, Ph.D., for helpful comments.

Dr. Merrick is a research associate with the Institute for Health Policy in the Heller Graduate School of Brandeis University. Address correspondence to her at Heller Graduate School, MS 035, Brandeis University, P.O. Box 9110, Waltham, Massachusetts 02454 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

|

Table 1. Net payments by health benefit plans for inpatient admissions for treatment of major depressive disorder in fiscal years before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out1

|

Table 2. Cumulative percentage of discharges with readmissions and follow-up services within 15 and 30 days of discharge after inpatient treatment for major depressive disorder before and after implementation of a behavioral health carve-out

1. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

2. Oss ME, Stair T: Managed Behavioral Health Market Share in the United States, 1996-1997. Gettysburg, Pa, Open Minds, 1996Google Scholar

3. Ma CA, McGuire TG: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

4. Frank RG, McGuire TG: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

5. Coulam RF, Smith JCH, Thompson JW, et al: Evaluation of the CPA-Norfolk Demonstration: Final Report. Cambridge, Mass, Abt, 1990Google Scholar

6. Callahan JJ, Shepard DS, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173-184, 1995Google Scholar

7. Dickey B, Norton EC, Normand S-L, et al: Massachusetts Medicaid managed health care reform: treatment for the psychiatrically disabled, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research, vol 15. Edited by Scheffler RM, Rossiter LF. Greenwich, Conn, JAI, 1995Google Scholar

8. Grazier KL, Scheffler RM, Bender-Kitz S, et al: The effect of managed mental health care on use of outpatient mental health services in an employed population, in Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research, vol 14. Edited by Scheffler RM, Rossiter LF. Greenwich, Conn, JAI, 1993Google Scholar

9. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17 (2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar

10. Stoner T, Manning W, Christianson J, et al: Expenditures for mental health services in the Utah prepaid mental health plan. Health Care Financing Review 18(3):73-93, 1997Google Scholar