Overcoming Service Barriers for Homeless Persons With Serious Psychiatric Disorders

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To help homeless persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders gain access to community services, in 1993 the Center for Mental Health Services implemented the five-year Access to Community Care and Effective Services, or ACCESS program, in 15 cities. One aim of the program is to encourage collaboration between agencies serving the multiple needs of this population. This study examined the extent of linkages between agencies in the 15 demonstration cities. METHODS: One respondent from each of the 1,060 community-based programs in the 15 cities rated the extent to which his or her agency was linked with each of the other agencies in the local community in 1994 and again in 1996. Overall, there were 20,801 potential pairwise linkages. Linkages were classified into four types: a mutual tie, in which both agencies send and receive clients; a unidirectional tie, in which one agency sends and the other receives; an attempted tie, in which one agency sends but the other agency does not confirm receiving; and an unattempted tie. RESULTS: In 1994 and 1996, of the 20,801 pairs of potential service linkages, about a third were in place, while the remaining two-thirds were absent. Overall, linkages showed a slight but significant increase between 1994 and 1996. More than half of the linkages changed in type, indicating fluid service systems. CONCLUSIONS: Linkages between community agencies serving homeless persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders are not extensive. However, they increased slightly under the first two years of the ACCESS program, and there are good reasons to anticipate greater improvements in the future.

Providers of treatment to persons with substance use and psychiatric disorders often voice frustration over revolving-door clients—those who are treated and who then relapse, only to return to treatment. This problem is perceived to be growing at the same time that a fundamental shift is occurring in the type of clients that community-based providers serve in outpatient settings. This client base now includes many homeless persons with multiple disorders such as serious psychiatric illness, substance abuse, and chronic health problems like HIV-AIDS (1).

When caring for these individuals, providers describe a range of service and organizational barriers, commonly cited in the literature (2). This clientele has multiple service needs and confronts barriers at both the front door—in getting access to service—and at the back door, with a lack of continuity planning and follow-up. Single service providers are unable to offer a continuum of care, relying instead on linkages to other community agencies.

Because this population is very costly to serve (3), a continuum of care is thought to be essential to reduce duplication of services and help balance strained budgets among public-sector, community-based providers of clinical and supportive services. Management of community-based services for the multiply diagnosed homeless population is critical in this regard. One national study has shown that the prevalence of co-occurring psychiatric disorders among persons entering treatment for substance abuse is 60 percent (4), with higher rates of comorbidity of psychiatric and substance use disorders among persons presenting at hospital emergency rooms.

Evidence also shows that this population is at increased risk for a litany of negative outcomes such as relapse (5,6), rehospitalization (7,8,9), increased psychotic symptoms (10,11), depression and suicidality (12), violence (13), incarceration (14), financial problems (15), inadequate housing and homelessness (11,16), treatment noncompliance (11), HIV infection (17), family burden (18), and increased service utilization in general (8). It was reported to Congress that it is costing $33 billion yearly to incarcerate drug offenders, a major portion of whom also have serious psychiatric disorders (19).

It is now shared wisdom that to manage chronic health disorders, treatment should be provided concurrently with supportive social services (1,20,21,22). However, major unresolved problems are the availability, accessibility, and integration of supportive services in local communities. Bachrach (23) noted that despite recent advances in disease management technologies, such as pharmacology, psychotherapy, and psychosocial rehabilitation, system-endemic barriers such as organizational arrangements and coordination are still obstacles to care. Not surprisingly, because few communitywide attempts have been made to coordinate services in local areas, historically efforts to achieve system-level integration have moved slowly.

Several studies have documented major problems in gaining access to local community-based services for homeless people with multiple disorders, but most of the studies are limited in scope. They involve only a few sites and program providers, plus they usually cover only a single period of time. In contrast, the study presented here provides data on service linkages among many types of service programs. Linkage data were gathered in 15 of the largest U.S. cities at two time points. These data allow for a more comprehensive assessment of the widely held perception of the lack of coordinated treatment in community-based settings for this population. In addition, the data allowed for quantifying reported service linkages among pairs of providers as well as determining how these linkages changed over time.

Methods

The data are from a national evaluation of the demonstration project sponsored by the Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS) entitled Access to Community Care and Effective Services, or the ACCESS program (24,25,26). This five-year demonstration project, which began in 1993, provides direct service dollars for outreach and case management to 100 homeless clients with serious psychiatric and substance use disorders at 18 urban sites for each year of the project (27). Although 15 cities are participating in ACCESS, three have two distinct demonstration sites, for a total of 18 sites.

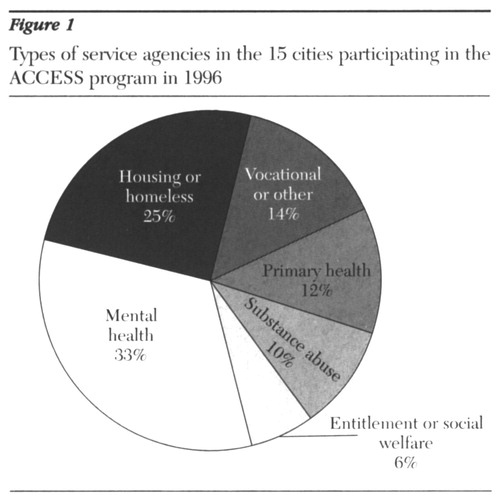

Figure 1 presents a profile of the types of organizations identified as serving the target population in the ACCESS service systems.

In addition, CMHS funds a national evaluation of the ACCESS demonstration that focuses on program implementation, system integration, and client outcomes. The system integration evaluation collects a broad range of service linkage data from service providers at each site who serve homeless persons with serious psychiatric and substance use disorders. Four waves of service linkage data will be gathered at these sites over the 1994-1999 period. This report relies on the first two waves of data (24) gathered in 1994 (wave I) and 1996 (wave II).

Service agencies in each city representing major components of the local community support system were selected for the study with the help of local ACCESS staff and key informants. Figure 1 shows that across the 15 cities, approximately 33 percent of the 1,060 participating agencies were identified as mental health programs, 25 percent as homeless or housing programs, 10 percent as substance abuse programs, 12 percent as programs that provided primary care or dental care or testing for sexually transmitted diseases, 6 percent as entitlement and social welfare programs, and the remaining 14 percent as other supportive services like vocational or advocacy programs.

Data collection

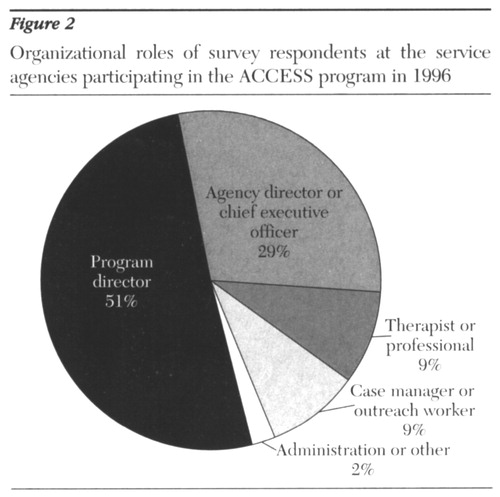

The primary data collection process is described in detail elsewhere (24). The two waves of data used in the study reported here were collected on site and in person by local teams comprising up to six interviewers and one site coordinator. One respondent per agency was interviewed. Respondents were identified as particularly knowledgeable about their program's service linkages. Refusal rates were approximately 3 percent in 1994 and 1996. Figure 2 describes the respondents in terms of their organizational roles. Of the 923 respondents for whom job titles were available, 29 percent were agency directors or chief executive officers, 51 percent were program directors, 9 percent were therapists or professionals, 9 percent were case managers or outreach workers, and 2 percent were administrators or in the category "other."

The variable of interest—service linkages for homeless persons with comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders—was measured through reported client referrals between the identified providers at each ACCESS site. The client referral linkages were measured by the question "To what extent does your organization send clients to or receive clients from this other agency specifically related to homeless persons with a severe mental illness?" The response categories ranged from 0, none, to 4, a lot. Data on both sending clients to other agencies and receiving clients from other agencies were collected at each time period.

The data were placed in two matrices, one for sending and one for receiving, in which the first row contains the first organization's response to all the other organizations, through to the last row, which contains the last organization's response to the other agencies. The data are dichotomized so that any relationship greater than 0 is counted as present, and all others are counted not present. Dichotomization overcomes a methodological concern that respondents might have different interpretations of the scale's anchors, which ranged from "not at all" to "a lot."

The unique pair ties between all agencies in a site were classified into one of four mutually exclusive categories: a mutual tie, in which both providers acknowledge a mutual sending and receiving relationship; a unidirectional tie, in which one provider sends clients and the other reports receiving clients; an attempted tie, in which a provider reports a sending relationship but the other agency does not confirm the relationship; and an absence of ties, in which no sending or receiving is attempted by either program.

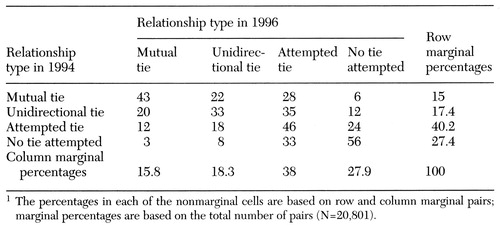

In the matrices, the four types of linkages are arrayed in order of increasing connectivity with no tie attempted the lowest and mutual ties the highest. By cross-classifying the linkage types for 1994 and 1996, both the existence of relationships between agencies and their changes between the two time points can be shown (see Table 1). The stability of each relationship type is indexed by values along the main diagonal of the first four columns in Table 1 (if drawn, the diagonal would connect the first value in column 1—43 percent—with the last value in column four—56 percent). All cells above the main diagonal of the table indicate deterioration in connectivity, whereas all cells below the main diagonal of the table indicate growth in connectivity. For ease of presentation, percentages rather than the actual number of linkages are displayed.

The significance of changes from 1994 to 1996 were assessed by McNemar's matched pairs test (28) computed on a 2 x 2 version of this table, in which the actual number of mutual and unidirectional ties were collapsed into one category and the actual number of attempted ties and no ties were collapsed into another. The test is distributed as a chi square with 1 degree of freedom.

Results

Table 1 aggregates the data across the 15 cities to answer two distinct questions. The first question is to what extent do client referral relationships exist for this population, and the second is in what ways do these linkages change over time?

The first question is answered by examining the row marginal percentages (column 5) in Table 1. Of the 20,801 pairs, 15 percent in 1994 were mutual relationships, and 17 percent were unidirectional. Thus established relationships existed for about a third of the possible ties. Two-thirds of the possible ties fell in the categories of attempted ties and no ties. This finding confirms that interagency relationships did exist for homeless mentally ill clients, but it underscores the sparseness of working service relationships among agencies in the local community that have daily contact with this population.

The second question is answered by comparing the 1994 distribution, shown in the last column of Table 1, with the 1996 distribution shown in the bottom row of Table 1. This comparison reveals a slight 2 percent increase in the mutual and unidirectional ties and a corresponding decrease in the categories of attempted ties and no ties. Otherwise, the two time periods are remarkably similar.

In contrast to the stability shown in the marginal percentages, the inner cells of Table 1 demonstrate that these service systems are very fluid, with many interagency ties forming, improving, or deteriorating between 1994 and 1996. Only 43 percent of the mutual ties remained stable, while 57 percent of the mutual ties deteriorated, with a shift either to unidirectional ties (23 percent), to attempted ties (28 percent), or to no ties attempted (6 percent). Similarly, only 33 percent of the unidirectional ties remained stable. Twenty percent of unidirectional ties improved by becoming mutual ties, while 47 percent deteriorated by becoming either attempted ties (35 percent) or no ties (12 percent).

Forty-six percent of the attempted ties remained stable between 1994 and 1996, while 30 percent improved as unidirectional ties (18 percent) or mutual ties (12 percent). However, this increased connectivity was offset by a 24 percent shift to the category of no ties attempted. Finally, 56 percent of ties not attempted in 1994 remained stable in 1996, while 44 percent improved as either attempted ties (33 percent), unidirectional ties (8 percent), or mutual ties (3 percent). Ties not attempted were the least likely to change over time.

The net effect of these relationship changes was an increase of 349 better-connected relationships, or approximately 19 ties per site. Although this effect is modest, the ratio of strengthened to weakened ties is statistically significant (χ2 =20.97, df=1, p<.001). Thus the evidence shows a tendency for client referral relationships among agencies serving homeless persons with serious mental illness to improve over time.

Discussion and conclusions

The findings corroborate anecdotal reports of community-based providers about service barriers for homeless persons with comorbid disorders. They also support claims that services for this population are often fragmented and inaccessible even when they exist. The extent of service linkages was found to be low across the 15 cities studied, but linkages increased slightly between 1994 and 1996. It is not known exactly what the acceptable percentage of ties should be to make a system of care "ideal." The figure will be something less than 100 percent because it is assumed that not all ties in a system should be realized. However, the data indicated that only one in three potential linkages was realized, which seems too few. The positive news is that one in five of the possible linkages were reciprocal and mutual—the type relationship thought to be necessary for a population that is mobile and harder to serve, and this linkage type increased slightly over time.

The improvements in interagency connectivity also speak to the impact of the ACCESS demonstration. The ACCESS program was initiated in 1993 as part of a national agenda to end homelessness among persons with a serious mental illness (26). The thinking that guided this effort was that system integration among mental health, substance abuse, primary health care, income maintenance, and housing agencies would improve outcomes for persons who were homeless and mentally ill. Outcomes were measured primarily in terms of quality of life and independent housing placements. Expectations at the beginning of the demonstration were that by the time the wave II data were collected, integration would be increased at the nine sites that received funding to implement system change strategies.

The system improvements reported in this study, however, are more modest than expected. It became increasingly apparent to the national evaluation team, based on extensive yearly site visits, semiannual reports from the program directors, and semiannual conferences (29), that the expectation of rapid system change was premature. Two basic reasons were noted. First, evidence was found of considerable confusion among local project staff about which proposed strategies could actually be implemented and how to initiate them, which resulted in hardly any system-level activity during the first two years. Second, little program money (if any) was actually spent on integration of systems and programs, with almost all expenditures going for direct services. Such integration was seen as harder to initiate than originally envisioned, and integration took a back seat to outreach and case management activities.

This realization prompted CMHS to sponsor an intensive four-day strategic planning conference for accomplishing system and service integration, with continued technical assistance to the sites. This assistance occurred after the wave II service linkage data were reported, which are the data reported here. Thus, the system-level interventions planned for ACCESS had hardly been applied when these data were collected. So the modest improvements reported in this paper are not surprising in this context.

The fluidity of interagency linkages, the deterioration of some links over time, and the large number of links that were never attempted at all speak to the growing challenges to publicly supported mental health and substance abuse services resulting from more conservative fiscal management strategies under managed behavioral health care, welfare reform, and program consolidations. These phenomena represent very real sociopolitical forces with real consequences. As managed care enters a service system, linkages tend to be constrained toward specified provider networks and the overall system may become more fragmented (30,31,32). Despite the growing economic prosperity of the United States, there are signs that the social safety net is fraying for homeless persons who are mentally ill.

To date, the ACCESS evaluation is clearly showing the difficulty of implementing systems integration quickly. The major reason for a lack of community service linkages has been acknowledged for some time and may explain why linkages never develop at all. The fact is that human services have never been organized into coherent systems; rather, mental health, substance abuse, social welfare, and so forth are each organized as systems unto themselves with different funding and accountability structures (33,34). Developing integrated service linkages across these sectors is fraught with difficult problems (35).

Aggregate analyses of the type presented here may also mask developments at the level of the individual site. Significant changes are expected between wave II and wave III, when the results from extensive technical assistance should be realized. Evidence of local efforts to implement integration has been noted in anecdotal reports gleaned from site visits conducted in spring 1997, and CMHS is continuing to provide technical assistance. This evidence suggests that the ACCESS staff have accelerated their system integration interventions and that the levels of system integration in the host communities are seen by many participants as improving. Now that system change efforts are under way, the national evaluation team is collecting information about the integration strategies that seem to be more realistic and easier to implement (29) and which of these strategies actually lead to improvements in system integration.

A sensitive test of the effectiveness of the ACCESS program requires a site-by-site analysis, which will be provided in a future report. The data reported here represent only the first two years of the five-year ACCESS intervention. Thus it is too early for a final assessment of the ultimate impact of this program on improving system integration. Again, the focus at most ACCESS sites during the first two years was on the development of clinical services rather than on systems integration.

Given the fact that integration efforts are under way, great attention will be focused in the two remaining years on gathering evaluation data about the success of ACCESS in achieving its ambitious goals for system integration. Two additional waves of interagency linkage data will be collected in early 1998 and late 1999. These data will afford an opportunity to assess whether systems integration improves during the remaining years of the ACCESS program and, ultimately, whether this improvement enhances client outcomes (27).

The authors are associated with the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research, CB 7590, 725 Airport Road, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7590 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

Figure 1. Types service agencies in the 15 cities participating in the ACCESS program in 1996

Figure 2. Organizational roles of survey respondents at the service agencies participating in the ACCESS program in 1996

|

Table 1. Percentage of four types of linkages between service agencies in 15 ACCESS demonstration cities and changes in linkage types between 1994 and 19961

1. Outcasts on Main Street: Report of the Federal Task Force on Homelessness and Severe Mental Illness. Washington, DC, US Department of Health and Human Services and the Interagency Council on the Homeless, 1992Google Scholar

2. Calloway MO, Ullman M, Morrissey JP: Service barriers faced by persons who are homeless with serious mental illness: perceptions of service providers in 15 US cities. Paper presented at a conference on Improving the Condition of People With Mental Illness: The Role of Services Research. Washington, DC, National Institute of Mental Health, Sept 4-5, 1997Google Scholar

3. Dickey B, Normand ST, Norton EC, et al: Managing the care of schizophrenia: lessons from a four-year Massachusetts Medicaid study. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:945-952, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

4. Flynn PM, Craddock SG, Luckey JW, et al: Comorbidity of antisocial personality and mood disorders among psychoactive substance-dependent treatment clients. Journal of Personality Disorders 10:56-67, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar

5. Woody GE, McLellan AT, Luborsky L, et al: Sociopathy and psychotherapy outcome. Archives of General Psychiatry 42:1081-1086, 1985Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

6. Rounsaville B J, Dolinsky ZS, Barbor TF, et al: Prognostic significance of psychopathology in treated opiate addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 43:739-745, 1987Crossref, Google Scholar

7. Seibel JP, Satel SL, Anthony D, et al: Effects of cocaine on hospital course in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:31-37, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

8. Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, et al: Substance abuse in schizophrenia: service utilization and costs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 181:227-232, 1993Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

9. Caton CLM, Wyatt RJ, Felix A, et al: Follow-up of chronically homeless mentally ill men. American Journal of Psychiatry 150:1639-1642, 1993Link, Google Scholar

10. Carey MP, Carey KB, Meisler AW: Psychiatric symptoms in mentally ill chemical abusers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 179:136-138, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Osher FC, Drake RL, Noordsy DL, et al: Correlates and outcomes of alcohol use disorder among rural outpatients with schizophrenia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 55:109-113, 1994Medline, Google Scholar

12. Bartels SJ, Drake RE, McHugo GJ: Alcohol abuse, depression, and suicidal behavior in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 149:394-395, 1992Link, Google Scholar

13. Cuffel BJ, Shumway M, Chouljian TL: A longitudinal study of substance use and community violence in schizophrenia. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 182:342-348, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

14. Abram KM, Teplin LA: Co-occurring disorders among mentally ill jail detainees. American Psychologist 46:1036-1045, 1991Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

15. Drake RE, Wallach MA: Substance abuse among the chronically mentally ill. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40:1041-1046, 1989Abstract, Google Scholar

16. Caton CLM, Shrout PE, Eagle PF, et al: Risk factors for homelessness among schizophrenic men: a case-control study. American Journal of Public Health 84:265-270, 1994Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

17. Hanson M, Cancel J, Rolon A: Reducing AIDS risks among dually disordered adults. Research on Social Work Practice 4(1):14-27, 1994Google Scholar

18. Clark RE: Family costs associated with severe mental illness and substance abuse: a comparison of families with and without dual disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:808-813, 1994Abstract, Google Scholar

19. The cost for incarcerating drug offenders. Substance Abuse Funding, Dec 22, 1997, p 5Google Scholar

20. Hubbard RL, Marsden ME, Rachal JV, et al: Drug Abuse Treatment: A National Study of Effectiveness. Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1989Google Scholar

21. Moos RH, King MJ, Patterson MA: Outcomes of residential treatment of substance abuse in hospital- and community-based programs. Psychiatric Services 47:68-72, 1996Link, Google Scholar

22. Weisner C: The alcohol-seeking process from a problems perspective: response to events. British Journal of Addictions 85:561-569, 1990Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

23. Bachrach LL: Breaking down the barriers: commentary on a conference theme. Psychiatric Services 48:281-294, 1997Link, Google Scholar

24. Morrissey JP, Calloway MO, Johnsen M, et al: Service system performance and integration: a baseline profile of the ACCESS demonstration sites. Psychiatric Services 48:374-380, 1997Link, Google Scholar

25. Randolph F, Blasinsky M, Leginski W, et al: Creating integrated service systems for homeless persons with mental illness: the ACCESS program. Psychiatric Services 48:369-373, 1997Link, Google Scholar

26. Randolph F: Improving service systems through systems integration: the ACCESS program. American Rehabilitation 21:36-38, 1995Google Scholar

27. Rosenheck R, Lam JA: Client and site characteristics as barriers to service use by homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services 48:387-392, 1997Link, Google Scholar

28. Stokes ME, Davis CS, Koch GG: Categorical Data Analysis: Using the SAS System. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1995Google Scholar

29. Cocozza J, Steadman H, Dennis DL: Implementing System Integration Strategies: Lessons From the ACCESS Program. Delmar, NY, Policy Research Associates, 1997Google Scholar

30. Johnsen M, Morrissey J, Landow W, et al: The impact of managed care on service systems for persons who are homeless and mentally ill, in Research in Community Mental Health: Social Networks and Mental Illness. Edited by Morrissey J. Stamford, Conn, JAI, 1998Google Scholar

31. Heflinger C, Northrup D: Measuring changes in mental health services coordination in managed mental health care for children and youth, ibidGoogle Scholar

32. Provan K, Milward B: Network evolution to a system of managed care for adults with severe mental illness: the Tucson experiment, ibidGoogle Scholar

33. Ridgely MS, Dixon L: Policy and financing issues, in Double Jeopardy: Chronic Mental Illness and Substance Abuse Disorders. Edited by Lehman AF, Dixon L. Chur, Switzerland, Harwood, 1995Google Scholar

34. Roemer R, Kramer C, Frink JE: Planning Urban Health Services: From Jungle to System. New York, Springer, 1975Google Scholar

35. Rowe M, Hoge MA, Fisk D: Critical issues in serving people who are homeless and mentally ill. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 23:555-565, 1996Crossref, Google Scholar