How a Managed Behavioral Health Care Carve-Out Plan Affected Spending for Episodes of Treatment

Abstract

OBJECTIVE: This study examined the impact on spending for episodes of mental health and substance abuse treatment of a managed behavioral health care carve-out program implemented by the Massachusetts Group Insurance Commission in July 1993. METHODS: Episodes of mental health and substance abuse treatment were defined using claims and enrollment data from before and after the carve-out implementation. Regression models were used to compare spending per episode for different types of episodes of mental health and substance abuse care: those involving care provided only in an inpatient facility (that is, inpatient care or partial hospitalization), those involving both inpatient-facility and outpatient care, and those involving only outpatient care. RESULTS: Adoption of the carve-out plan was associated with a large decrease in spending per episode across all three episode types, particularly for episodes involving inpatient-facility care. The decrease was 54 percent for inpatient-facility-only episodes, 46 percent for combined inpatient facility and outpatient episodes, and 21 percent for outpatient-only episodes. The decrease in spending per episode was larger for episodes involving a diagnosis of either unipolar depression or substance dependence. CONCLUSIONS: The findings suggest that spending per episode of mental health and substance abuse treatment may drop substantially after a carve-out is implemented. Individuals with a diagnosis of either unipolar depression or substance dependence seem to be disproportionately affected. It appears that even weak financial incentives placed on the managed behavioral health care vendor can result in dramatic changes in spending patterns for episodes of mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Over the past several years, a large number of private employers and state governments have carved out the mental health and substance abuse benefit from the health insurance plans they sponsor and contracted with a specialty managed care vendor to manage this benefit for all their enrollees. As of January 1997, approximately 71 million individuals, including employees of private firms, state government employees, Medicaid enrollees, and Medicare enrollees, were covered under managed behavioral health care carve-outs that place the vendor at financial risk for claims costs (1,2).

Managed behavioral health care vendors use care management techniques, including utilization management and exclusive provider networks, as mechanisms for controlling claims costs (3,4). Proponents of managed care assert that application of care management techniques to the provision of mental health and substance abuse services will result in a more appropriate match between service use and clinical need. They argue that by reducing unnecessary utilization, care management will allow vendors to channel more resources to those with severe conditions. Critics of managed care are concerned that the use of care management techniques by vendors who face financial incentives to control costs will result in undertreatment or poor quality of care.

Several studies of individual managed behavioral health care carve-outs have documented large savings in aggregate costs for mental health and substance abuse services in the first year after a carve-out is implemented (5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13; Huskamp H, unpublished manuscript, 1997). To begin to understand how carve-outs affect treatment that enrollees receive for mental health and substance abuse problems, one needs to know not just how aggregate spending for these services may have changed but also how expenditures for treatment episodes are affected. This study examined spending for episodes of treatment by enrollees of a carve-out plan implemented in Massachusetts.

The carve-out

The Massachusetts Group Insurance Commission has the statutory responsibility for providing health insurance coverage to Massachusetts state employees, retirees, and their survivors and dependents. In the early 1990s, the commission became concerned by two trends. First, mental health and substance abuse costs, which were high relative to such costs for other employed populations, were rising. Second, individuals who were more likely to use services seemed to be enrolling disproportionately in the indemnity plan, resulting in increasing premium costs (14). To address these issues, the commission signed a managed behavioral health care carve-out contract for its indemnity and preferred-provider-organization plans with Options Mental Health on July 1, 1993. (Enrollees in health maintenance organizations were excluded.)

The contract brought about several changes in the management and design of the mental health and substance abuse benefit. Under the old indemnity plan, the insurer was paid a fee to manage the benefit but did not assume financial risk for claims costs. Under the carve-out, the vendor and the state share financial risk: a portion of the vendor's fee is at risk on the basis of claims experience.

In the first year of the contract, the vendor received a fee of $3.43 per primary insured person per month if claims fell below a monthly claims target of $20.72 per primary insured person, an amount comparable to prior expenditure levels. (A primary insured person includes all family members covered under the same insurance contract.) If claims exceeded the target, the vendor's fee would drop by 20 percent of the amount by which they exceeded the target, up to a maximum loss of 20 percent of the fee. For the second year, the fee was lowered to $3.17, and the claims target was reduced to $15.39.

The vendor was also at financial risk for meeting five performance standards, including standards governing speed in answering the clinical referral line and in processing claims. Options Mental Health could lose 2 percent of its fee for each standard it failed to meet, subject to a maximum loss of 23 percent of its fee for both claims and performance outcomes.

In addition, a provider network was developed, and discounted fees were negotiated. The mental health and substance abuse benefit was expanded, particularly for outpatient care, and coverage of partial hospitalization was added. Finally, a utilization review program was added for outpatient care. Under this program, an enrollee calls a toll-free number to obtain a referral. After completing each set of ten outpatient visits, the enrollee undergoes utilization review to obtain coverage for additional visits.

By placing the vendor at risk for the level of claims, the contract created a direct incentive to control expenditures. However, this incentive was fairly weak relative to a more high-powered contract like pure capitation. Options Mental Health lost only 20 cents on the dollar for all claims costs over the target, and those losses were limited so that the vendor could never earn less than 80 percent of its fee regardless of how high claims costs were. The vendor also had an indirect incentive to perform well because the contract with the Massachusetts General Insurance Commission was one of its first large contracts and the firm hoped to build a strong reputation in the market (12).

Editor's Note The first five articles in this issue constitute the second of two special sections of papers on mental health services research by new investigators, researchers whose work has not been published extensively in the professional literature. The first group of papers was published in the August issue. Both special sections were developed by Psychiatric Services editorial board members Howard H. Goldman, M.D., with assistance from Richard G. Frank, Ph.D., of the department of health care policy at Harvard University.

Methods

I linked enrollment data with data from facility and outpatient mental health and substance abuse claims for the period beginning October 1, 1991, and ending March 30, 1995. Claims data for pharmaceuticals prescribed for mental health and substance abuse conditions, which were not included under the carve-out, were not available. In the claims data, "facility care" is a category used to describe all services provided by inpatient facilities. Facility care thus includes traditional inpatient services and partial hospitalization services provided by inpatient facilities.

To examine how the carve-out influenced mental health and substance abuse treatment, I defined treatment episodes using the approach of Kessler and associates (15). If more than eight weeks pass between two mental health or substance abuse treatment encounters of any kind, the second encounter is considered the start of a new episode. Using this definition, there were 33,407 episodes during the study period.

Episodes were divided into three groups: facility-only episodes (involving inpatient or partial hospitalization services provided by inpatient facilities), outpatient-only episodes (involving only outpatient services, including partial hospitalization provided by outpatient facilities), and facility-outpatient episodes (involving both types). Episodes are referred to as pre-carve-out if the episode began and ended before the carve-out was implemented, and post-carve-out if the episode began after implementation. The pre-post marker was the day the carve-out was implemented—July 1, 1993. Episodes that began before implementation but ended afterward are called overlap episodes. Because these episodes were subject to the new program for only part of their duration, they were excluded from the analyses of the carve-out's impact and were examined separately to see how their exclusion might affect the results.

I used regression models to examine the effect of the carve-out on total mental health and substance abuse spending per episode and on outpatient mental health and substance abuse spending per episode for each of the three episode types. A logarithmic transformation of the dependent variables was used to address skewness in the distribution of these variables.

The models controlled for age, gender, status of the insured (employee, spouse, or dependent), and whether the enrollee had a previous mental health and substance abuse episode during the study period. I also included dummy variables that indicated whether the enrollee had a diagnosis of one of four severe conditions: unipolar depression (ICD-9 four-digit codes 296_, 2962, and 2963), schizophrenia or bipolar depression (ICD-9 three-digit code 295 and four-digit codes 2960, 2961, and 2964 to 2968), or substance dependence (ICD-9 three- digit codes 303 and 304).

The key independent variable is a dummy variable that indicates whether the episode began after the carve-out was implemented or whether the episode began and ended before implementation. Interaction variables were used in some specifications of the model to indicate whether the carve-out may have disproportionately affected treatment expenditures for enrollees with certain severe conditions.

Results

Spending per episode

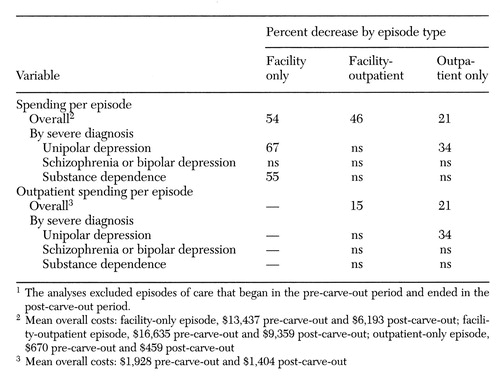

After the carve-out was implemented, mental health and substance abuse spending per episode for all three episode types decreased, although the decreases were larger for episodes involving facility care. (Overlap episodes were not included in these analyses.) As Table 1 shows, after the carve-out was implemented, total expenditures per episode were 54 percent lower for facility-only episodes, 46 percent lower for facility-outpatient episodes, and 21 percent lower for outpatient-only episodes. The smaller decrease for outpatient-only episodes may be due in part to the expansion of the outpatient benefit.

The impact of the carve-out on total expenditures per episode seemed to disproportionately affect individuals with a diagnosis of unipolar depression or substance dependence. Expenditures for facility-only episodes involving one of these diagnoses decreased at a greater rate than expenditures for facility-only episodes that did not involve these conditions—a 67 percent decrease for unipolar depression and a 55 percent decrease for substance dependence, compared with a 31 percent decrease for other conditions.

For enrollees who used both facility and outpatient services and had one of the severe conditions, no significant difference was found between the percentage decrease in total spending per episode for those with one of the severe conditions and for all other users of mental health and substance abuse services. However, for enrollees who used only outpatient services and who had a diagnosis of unipolar depression, the carve-out was associated with a 34 percent decrease in spending per episode, compared with a 19 percent decrease for enrollees who used only outpatient services and who did not have one of the severe conditions.

Overlap episodes

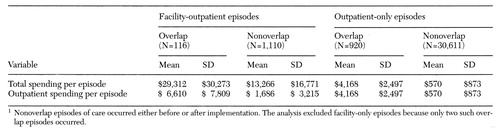

Table 2 shows data for episodes that began before the carve-out was implemented and ended after implementation. Much higher mean costs per episode were found for overlap episodes than for pre-carve-out or post-carve-out episodes. This finding suggests that the analyses of spending per episode described above may have disproportionately excluded individuals who had more severe conditions or who may have been predisposed to use a high level of services. As a result, the effect of the carve-out on spending per episode for individuals with severe conditions may not have been fully captured.

Discussion and conclusions

Three major conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, less money was spent per episode of mental health and substance abuse treatment after the Massachusetts General Insurance Commission implemented a managed behavioral health care carve-out plan. Decreases in spending per episode were particularly dramatic for episodes involving facility care (inpatient care and partial hospitalization provided in an inpatient facility). This result is consistent with the typical vendor strategies of reducing inpatient expenditures and substituting less expensive partial hospitalization and outpatient services for inpatient care.

The second conclusion is that individuals with a diagnosis of either unipolar depression or substance dependence seemed to be disproportionately affected by the carve-out plan. A previous study of the Massachusetts carve-out plan found that it resulted in a shift in the site of treatment away from facility care and toward the use of outpatient care, particularly for individuals with a diagnosis of unipolar depression (Huskamp HA, unpublished manuscript, 1997). As a result of this shift, some individuals who had been considered "sick" enough to receive facility services in the past would now receive only outpatient services.

Under these circumstances, one might expect to see increases in spending per episode for outpatient-only episodes of individuals with serious conditions. I did not find such increases in spending and instead found decreases in some cases. The finding suggesting a disproportionate effect on enrollees with certain severe illnesses appears to conflict with the argument that managed care will result in more resources being devoted to those with severe conditions.

The third conclusion to be drawn from this study is that it appears that the incentives faced by the vendor resulted in dramatic changes in the spending patterns for episodes of treatment. The finding suggests two possibilities. First, vendors may be very sensitive to even weak financial incentives to control costs like those found in the Massachusetts contract. Second, the reputation effect, whereby the vendor tailors performance on a current contract to impress potential clients, may have been an important determinant of spending.

This study examined the experience of one carve-out only, and because pharmacy data were not available, I was unable to examine how the use of pharmacological interventions may have changed after the carve-out was implemented. For example, if the vendor shifted patients away from psychotherapy and onto medications (for which the vendor was not at risk), this change would appear as a decrease in spending per episode. Also, the study did not determine the extent to which the lower levels of spending per episode were a result of the provision of fewer services per episode or the result of cuts in providers' fees. Finally, given that the analyses seemed to exclude some of the individuals with the most severe conditions, the findings may not adequately capture the impact of a carve-out on individuals with severe mental health and substance abuse conditions.

More research is needed to understand how a carve-out affects treatment patterns. Nevertheless, these findings suggest that spending per episode of mental health and substance abuse treatment may drop substantially after a carve-out is implemented, even when the contract contains relatively weak financial incentives. The results also imply that enrollees with certain severe conditions may be disproportionately affected when a carve-out is adopted.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges financial support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (cooperative agreement P50 DA10233), the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. The author thanks the Group Insurance Commission for providing access to data.

Dr. Huskamp is assistant professor of health economics in the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115 (e-mail, [email protected]). This paper is one of several in this issue on mental health services research conducted by new investigators.

|

Table 1. Significant decreases in spending per episode of mental health and substance abuse care after implementation of a managed behavioral health care carve-out in Massachusetts, by type of episode1

|

Table 2. Spending per episode of mental health and substance abuse care for episodes that overlapped and did not overlap the implementation period of a managed behavioral health care carve-out in Massachusetts1

1. Oss M, Drissel A, Clary J: Managed Behavioral Health Market Share in the United States, 1997-1998. Gettysburg, Pa, Open Minds, 1997Google Scholar

2. Huskamp H: State Requirements for Managed Behavioral Health Care Carve-Outs and What They Mean for People With Severe Mental Illness. Arlington, Va, National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, Nov 1996Google Scholar

3. Frank RG, McGuire TG, Newhouse JP: Risk contracts in managed mental health care. Health Affairs 14(3):50-64, 1995Google Scholar

4. Frank RH, Huskamp T, McGuire TG, et al: Some economics of mental health "carve-outs." Archives of General Psychiatry 53:933-937, 1996Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

5. McDonnell Douglas Corporation: Employee Assistance Program Financial Offset Study, 1985-1988. Washington, DC, Alexander Consulting Group, 1989Google Scholar

6. Burton W, Hoy D, Bonin R, et al: Quality and cost-effective management of mental health care. Journal of Occupational Medicine 31:363-367, 1989Medline, Google Scholar

7. Callahan JJ, Shepard DJ, Beinecke RH, et al: Mental health/substance abuse treatment in managed care: the Massachusetts Medicaid experience. Health Affairs 14(3):173-184, 1995Google Scholar

8. Frank R, McGuire T: Savings from a Medicaid carve-out for mental health and substance abuse services in Massachusetts. Psychiatric Services 48:1147-1152, 1997Link, Google Scholar

9. Goldman W, McCulloch J, Sturm R: Costs and use of mental health services before and after managed care. Health Affairs 17(2):40-52, 1998Google Scholar

10. Hodgkin D: The impact of private utilization management on psychiatric care: a review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health Administration 19:143-157, 1992Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar

11. Integrated carve-out plan reduces behavioral health costs. Open Minds 9(10):10, 1993Google Scholar

12. Ma CA, McGuire T: Costs and incentives in a behavioral health carve-out. Health Affairs 17(2):53-69, 1998Google Scholar

13. Rodriguez A, Maher J: Psychiatric case management offers cost, quality control. Business and Health, Mar 1986, pp 14-17Google Scholar

14. Request for Proposal for Integrated Employee Assistance and Mental Health and Substance Abuse Program. Boston, Group Insurance Commission, Oct 16, 1992Google Scholar

15. Kessler L, Steinwachs D, Hankin J: Episodes of psychiatric utilization. Medical Care 18:1219-1227, 1980Crossref, Medline, Google Scholar