Preferences for Psychiatric Advance Directives Among Latinos: Views on Advance Care Planning for Mental Health

Psychiatric advance directives allow persons with mental illness to declare preferences for treatment through an advance instruction, a health care agent, or both. Evaluations of clinical and facilitation-completion outcomes are promising ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). However, the role of these directives in the cross-cultural context of mental health services is unexamined. These legal mechanisms may play an important role for Latino individuals in U.S. mental health care settings.

Psychiatric advance directives may help to align culturally appropriate services with treatment needs in Latino populations. This study assessed demand for, interest in, and attitudes toward psychiatric advance directives for Latino clients and their families and clinicians.

Methods

This study included data from 85 Latino adults with mental illness, 25 family members, and 30 clinicians. Data were collected between December 2007 and June 2008. Inclusion criteria for clients were Latino ethnicity, age 18 or older, diagnosis of schizophrenia or mood disorder, and at least one psychiatric hospitalization. Clients were randomly selected from management information system data from one of South Florida's largest treatment providers. Eighty-five of 100 clients who met study criteria consented to participate. Consenters and refusers did not differ by sex, age, or diagnosis.

Family members were eligible if they had a relative who met the above criteria. Twenty of the 25 family members (80%) were related to a client in the study. Eligible clinicians had treated ten or more individuals with severe mental illness in the past year and had a caseload of which at least 50% were Latinos.

Graduate-level research assistants administered a structured interview using instruments from a recent study ( 2 ). The interview assessed indirectly the association between culture and interest in psychiatric advance directives. Participants were told that culture represented unique or special factors—such as language, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors—common to members of one ethnic group or another ( 5 ). Interviewers provided three examples: use of the term ataque de nervios to describe mental health problems, reluctance to disclose personal information for fear of shaming family, and use of culturally specific treatments— curanderismo or remedios —for mental health problems.

All measures were translated to Spanish and back to English. Most interviews (90%) were done in Spanish. Participants were paid $25. The protocol was approved by Florida International University's institutional review board.

Results

The clients' mean±SD age was 53.40±13.01, and 56 (66%) were women. Sixty-eight clients (80%) were from Cuba; nine (11%) were from Puerto Rico; and the rest were from Colombia (N=4, 5%), Nicaragua (N=2, 2%), or the Dominican Republic (N=2, 2%). Twenty-eight clients (33%) had a chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, and the remaining had major depression (N=30, 35%) or bipolar disorder (N=27, 32%). Clients felt they did not speak English well (4.26±1.33) and were not comfortable speaking English (4.23±1.35). Both of these factors ranged from 1 to 5, with 5 indicating more negativity.

The mean age of family members was 56.40±16.73, and 17 (68%) were women. Fifteen (60%) were parents, five (20%) were adult children, four (16%) were spouses, and one (4%) was a sibling. The mean age for clinicians was 41.19±10.64 years, 22 (73%) were women, and 20 (67%) were Latino. Twenty clinicians (67%) held a master's degree, five had an M.D., and five a bachelor's degree.

Nine clients (11%) had previously expressed future treatment preferences. Five told a family member, whereas the others told a friend. Seventy-one clients (84%) wanted to complete a psychiatric advance directive. Among those, 45 (63%) wanted both an advance instruction and a health care agent, 20 (28%) wanted only a health care agent, and six (8%) wanted only an advance instruction.

Although only three family members had prior knowledge of psychiatric advance directives, 24 family members (96%) endorsed them. Similarly, 28 clinicians (93%) endorsed psychiatric advance directives, yet only three clinicians (10%) had a client who had one.

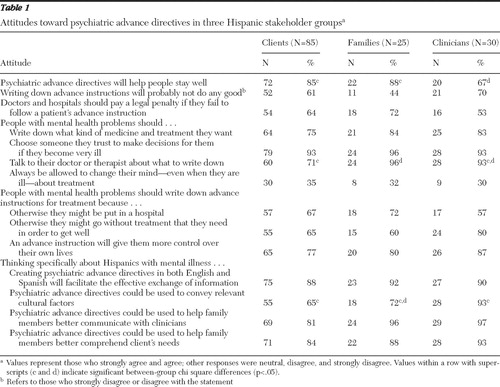

Table 1 presents data from between-group comparisons. Clinicians were less likely than clients or families to believe that psychiatric advance directives would help people stay well. Clients were less likely than others to think they should consult their clinician about what to write in the psychiatric advance directive. Finally, clinicians were more likely than clients or their families to think that psychiatric advance directives could be used to convey culturally specific information.

|

Clients ranked seven factors for importance (range 1–8, with 8 indicating most important). Doctor-recommended treatment (prescriptive function) was most important (7.84±2.34). This was followed by having a family member or friend provide support when completing a directive (7.53±2.47), surrogate decision making (7.34±2.72), avoiding unwanted treatment (proscriptive function) (6.09±3.09), changing one's mind when ill (irrevocability) (6.09±3.09), not letting family or friends know about treatment (confidentiality) (3.56±2.81), and involving one's religious leader (3.23±2.92).

Fourteen (16%) clients did not want to complete a psychiatric advance directive. The principal reason cited by 12 (86%) of those clients was not knowing what to include. The documents were viewed as too cumbersome by 11 (79%) clients. Thinking advance instructions would not make a difference in treatment was a concern for ten (71%) clients. Nine (64%) clients cited not liking to sign legal documents. Seven (50%) clients reported not understanding psychiatric advance directives; six (43%) indicated not having anyone to trust, including three clients (21%) who reported not having a doctor to trust.

Discussion

Empirical information has been lacking about whether psychiatric advance directives, despite their promise and potential importance to consumer-driven care, are acceptable and desired by Latinos with mental health problems. These new data show strong support for psychiatric advance directives in Latino mental health stakeholder groups. Psychiatric advance directives may complement Latino culture by reinforcing the centrality of families by allowing for client-family collaboration in completing these documents or allowing for surrogate decision making during crises. In prior research, 180 of 1,001 (18%) participants in a mainly African-American and white sample wanted to complete only an advance instruction ( 6 ), which can limit the role of surrogates. The data presented here showed that six of 71 clients (8%) preferred a stand-alone advance instruction; however, 65 clients (92%) wanted either a health care agent or an agent plus an advance instruction.

Preferences for psychiatric advance directives have also been examined ( 7 ). The strongest preference in both this study and the prior study was for the prescriptive function of these documents. In this research there was more emphasis on surrogate decision making and less on proscriptive decisions. Participants in both studies viewed irrevocability of decisions as relatively unimportant. The remaining factors were unique to this study and thus cannot be placed in the context of prior research.

Psychiatric advance directives may also address treatment barriers for Latinos. Across the three stakeholder groups in this study, 125 participants (89%) thought that bilingual documents would improve communication between families and clinicians. Clinicians also endorsed psychiatric advance directives at a rate higher than has been found in prior research ( 8 ). In addition, 28 (93%) clinicians thought that psychiatric advance directives could convey cultural preferences.

Social anthropologists have defined culture broadly as a group's shared patterns of thinking, feeling, believing, relating, and communicating, plus the symbols and actions that link these elements into "webs of significance" ( 9 ). From this perspective, systems of meaning may collide and break down when Spanish-speaking individuals from Latin America seek mental health care and encounter English-speaking clinicians in conventional care settings in the United States. In such cases, psychiatric advance directives may play a role in "translating"—symbolically and literally—the Latino patient's past experiences, current understandings, and future preferences for treatment.

Although psychiatric advance directives may play a role in cross-cultural mental health care, culture also plays a role in the directives. First, these documents are vehicles for communication, which is intrinsic to culture. Second, subjective information conveyed in the directives is suspended in cultural beliefs about mental illness, its causes, and what should be done about it. Third, authorization of surrogate decision makers is intertwined with social and familial relationships that are part of the web of culture. Fourth, the directive itself may acquire symbolic meaning to the individual in ways that are shaped by culture and by the felt need for empowerment for persons who are culturally marginalized.

This being the first study to examine these issues with Latinos, there are limitations. Samples were small, which limited multivariable analyses. Most participants were Cuban. More research should be conducted with other Latino groups to better understand intraethnic differences. The clients in this study were in treatment. Latinos not in treatment may have viewed psychiatric advance directives more negatively.

Rather than directly assessing participants' cultural views of psychiatric advance directives, we gave examples of culturally specific concepts and views of mental health and treatment and assessed whether they were associated with desire for psychiatric advance directives. Future research should further explore cultural characteristics that may affect Latinos' actual use of these legal mechanisms.

Conclusions

There has been little research into how people from ethnic minority groups view psychiatric advance directives. This study showed high interest and demand for psychiatric advance directives among Latino mental health stakeholder groups. Their interest related strongly to their desire to involve surrogate decision makers in mental health care decisions. Latinos may also wish to use psychiatric advance directives to express culturally specific understandings and treatment preferences.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The work was supported by the Florida International University Foundation.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Elbogen EB, Swanson JW, Appelbaum P, et al: Competency to complete psychiatric advance directives: effects of facilitated decision making. Law and Human Behavior 31:275–289, 2007Google Scholar

2. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Facilitated psychiatric advance directives: a randomized trial of an intervention to foster advance treatment planning among persons with severe mental illness. American Journal of Psychiatry 163:1943–1951, 2006Google Scholar

3. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Elbogen EB, et al: Psychiatric advance directives and reduction of coercive crisis interventions. Journal of Mental Health 17:255–267, 2008Google Scholar

4. Van Dorn RA, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al: Reducing barriers to completing psychiatric advance directives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 35:440–448, 2008Google Scholar

5. Alegría M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, et al: Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 13:208–220, 2004Google Scholar

6. Swanson JW, Swartz MS, Ferron J, et al: Psychiatric advance directives among public mental health consumers in five US cities: prevalence, demand, and correlates. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law 34:43–57, 2006Google Scholar

7. Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Van Dorn RA, et al: Preferences for psychiatric advance directives: results from a randomized trial of facilitation of psychiatric advance directives. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health 5:67–81, 2006Google Scholar

8. Elbogen EB, Swartz MS, Van Dorn RA, et al: Clinician decision-making and attitudes on implementing psychiatric advance directives. Psychiatric Services 57:350–355, 2006Google Scholar

9. Geertz C: The Interpretation of Cultures. New York, Basic Books, 1973Google Scholar