Inconsistencies in Diagnosis and Symptoms Among Bilingual and English-Speaking Latinos and Euro-Americans

Affective disorders are a primary contributor to the global burden of disease, and persons of Latino origin residing in the United States have higher rates of seeking treatment for depression than Euro-Americans ( 1 , 2 ). Previous studies have reported disproportionate rates of clinical diagnoses of major depression among Latinos ( 1 ). Little is known about the accuracy of diagnosing affective disorders among Latino patients, despite the direct impact on clinical care. Accurate diagnosis is linked to effective treatment, and clinical diagnostic error may have serious consequences ( 3 ).

The possible influences of culture and language used (for example, English, Spanish, or both languages) on Latinos' symptom presentation are understudied yet are considered threats to diagnostic accuracy. Because wide variations in English and Spanish language fluency exist among both patients and clinicians, misunderstandings in communication leading to misinterpretations of clinical signs and symptoms can occur. Culture may also influence the presentation of Latino patients' symptoms in frequency of occurrence or omission and in idiosyncratic expressions. Greater severity of psychopathology has been linked to psychosis among Latinos ( 4 ). These symptoms include hearing voices or noises that others cannot hear and feeling touched when there is no one else present ( 5 ). A tendency of Latinos to report putative psychotic symptoms has been reported in primary care and specialty mental health treatment settings and in psychiatric epidemiologic field studies ( 1 , 6 ).

Patient and clinician language use and comprehension have been closely scrutinized as potential sources of error in the diagnostic process. Two studies reported that disclosure of psychotic symptoms and more severe symptom ratings were more likely to occur in Spanish- than in English-language evaluations of Latino patients ( 7 , 8 ). Yet another study found that English-language interviews of patients with schizophrenia resulted in disclosure of more total pathology than Spanish speakers ( 9 ). In the largest study available, Latinos with schizophrenia who responded bilingually (that is, in both English and Spanish) during a diagnostic interview had the most severe symptom ratings, followed by those who spoke only Spanish and then by those who spoke only English ( 10 ). Latino clinicians rated symptoms more severely than did Anglo clinicians ( 10 ). A more recent study reported that English-speaking clinicians reported higher confidence in their assessments of Latino patients when interpreters (Spanish to English) were used ( 11 ). Without interpreters, English-speaking clinicians reported that patient diagnoses and functioning would have been assessed as less severe or the same. Notwithstanding a tendency toward less severe symptom reports when English-speaking clinicians diagnose Spanish-speaking patients, the evidence remains inconclusive. Noncomparability of designs, inconsistent use of research diagnostic interviewing, and the very small samples used in some of the cited studies undermine firm conclusions. An implication from previous research is that many diagnostic issues remain unresolved because findings are contradictory regarding language effects on the diagnostic process.

This study compared independent research diagnostic assessments of Latinos and Euro-Americans that were conducted by research interviewers who had good interrater reliability. The analyses focused on bilingual Latinos, Latinos who spoke only English, and non-Latino Euro-Americans. The study addressed two central research questions: Are previous findings of disproportionate rates of clinical diagnoses of major depression among Latinos replicated when structured diagnoses are applied? Are diagnostic patterns consistent with symptomatology, functioning, and other information among the same patients?

Methods

Participants were Latino and non-Latino Euro-American patients aged 18 to 45 years presenting for clinical services between January 2006 and May 2008 at three sites as part of a national study to identify the role of ethnicity in the diagnoses of affective disorders. The three sites were the University Behavioral Health Care of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey; the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio; and the University of California, Los Angeles.

Study protocols were approved by each site's institutional review board. Patients with a history of depression or psychotic symptoms were recruited. Participants provided written informed consent and gave permission for audiotaping their interviews and the release of their medical records. Initial assessment included the structured Diagnostic Interview for Genetic Studies (DIGS). Interviewers were trained to follow up on answers to questions in order to establish the presence or absence of specific psychiatric symptoms (either current or past) with a high degree of interviewer consistency and interrater reliability. The DIGS is also designed to elicit course of illness information (such as duration of illness) and to clarify temporal relationships among different diagnoses and symptoms (for example, psychosis or mood disorders). The interview covered three key diagnostic categories: affective disorders, schizophrenia, and substance use disorders. A complete medical history was taken. Diagnostic criteria can then be applied to this information in order to render diagnoses using a wide variety of criteria sets. DSM-IV diagnostic criteria were used in this study. As part of the DIGS we obtained a Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF) for each participant.

Additional symptom measures included the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). The ratings of trained diagnostic interviewers were calibrated for accuracy within acceptable ranges on each diagnostic module. All raters were trained to similar levels of competency using group ratings in national meetings.

Using all information from the interview and medical record, the interviewer provided a best estimate of diagnoses applicable to the patient and rated the patient with respect to severity of depression (MADRS), mania (YMRS), and four psychotic symptoms (delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder, and bizarre behavior, as measured by SAPS).

Results

We enrolled 259 participants from the three sites. There were 73 from the New Jersey site, 91 from the California site, and 95 from the Texas site; 119 (46%) were non-Latino Euro-Americans (40 persons, or 55%, at the New Jersey site; 38 persons, or 42%, at the California site; and 41 persons, or 43%, at the Texas site), and 140 (54%) were Latino. Within the Latino sample, 45 (32%) were bilingual and 95 (68%) spoke only English. Women constituted the majority of the sample (N=154, 59%).

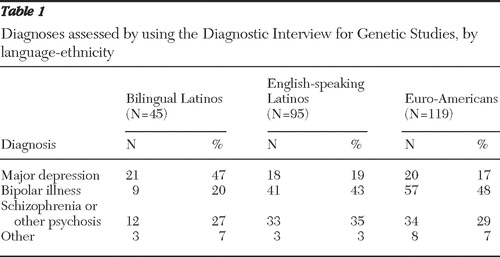

Table 1 presents the profile of DIGS-based diagnoses for each of the three main study groups (Euro-Americans, monolingual English-speaking Latinos, and bilingual Latino). There was a significant relationship between diagnosis and ethnic group (Fisher's exact test, p=.002). Disproportionate rates of major depression were found for the three study groups, with bilingual Latinos more likely than the other two groups to have a diagnosis of major depression.

|

In order to examine these observed associations of ethnicity and language with rates of major depression in the context of other independent variables, logistic regression (not shown) was performed for a single dependent binary variable: presence or absence of clinical diagnosis of major depression. Independent variables in these logistic regressions consisted of sex, age, site, income, and the three ethnicity-language study groups (bilingual Latino, monolingual English-speaking Latino, and non-Latino Euro-American). In this logistic model, main effects were significant for age ( χ2 =6.2, df=2, p<.05), site ( χ2 = 10.1, df=2, p<.007), and ethnicity-language ( χ2 =11.4, df=2, p<.003). Main effects were not significant for sex.

Bilingual Latinos were four times more likely than Euro-Americans to have a diagnosis of major depression (odds ratio [OR]=4.09, 95% confidence interval [CI]=1.81–9.23, p<.003). However, the odds of having a diagnosis of major depression did not differ significantly between monolingual English-speaking Latinos with Euro-Americans (OR=1.74, CI=.81–3.74). The odds ratios associated with other significant main effects obtained in this sample indicated that diagnoses of major depression decreased with age and were more prevalent at the New Jersey site than at the other two sites, although this finding was not significant. Key interaction terms (including site by ethnicity-language and age by ethnicity-language) were also tested in an expanded logit model, but these interactions were not significant.

In a regression analysis that controlled for age, site, sex, and income, the effect of the ethnicity-language factor on functioning was not significant. Overall, the mean level of functioning for bilingual Latinos (least-squares mean=53.6, CI=49.4–57.9) as measured by scores on the GAF was slightly higher but comparable to that for English-speaking Latinos and for Euro-Americans. (Possible scores on GAF range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing better functioning.)

Least-squares means and CIs for all the symptom scales were also estimated by study group (results not shown). In these regression analyses conducted for symptom variables, the only significant ethnicity-language effect (again after the analysis controlled for sex, site, income, and age group) was observed for the total score on the YMRS (F=3.71, df=2 and 250, p=.026). Bilingual Latinos had significantly lower scores on the YMRS compared with the other two groups, indicating that bilingual Latinos had lower levels of mania.

Discussion

This study was designed to address two central research questions: Are previous findings reporting disproportionate rates of clinical diagnoses of major depression among Latinos replicated when structured diagnoses are applied? Are these diagnostic patterns consistent with phenomenology, functioning, and other information measured from the same patients?

The answer to the first question is a qualified yes. Compared with Euro-Americans, bilingual Latinos, but not monolingual English-speaking Latinos, were disproportionately diagnosed as having major depression when structured diagnoses (DIGS) were used. In fact, the diagnostic pattern ( Table 1 ) for monolingual English-speaking Latinos was similar to that obtained for Euro-Americans. This finding suggests a possible association between English as a second language and cultural influences on the diagnostic process. All interviews were conducted in English, so interviewer language effects were controlled for but not fully examined.

Are the diagnostic patterns in this study consistent with other information measured from the same patients? Levels of mania, as measured by YMRS, were significantly lower among bilingual Latinos, compared with Euro-Americans. The lower levels of mania for bilingual participants are consistent with lower rates of bipolar illness reported in this group. This suggests the possibility that mania symptoms are less likely to be probed, detected, or disclosed among bilingual Latino patients, and it remains unclear whether this is due to idiosyncrasies in patient symptom presentations or results from faulty patient-clinician communication.

There was no significant difference in level of functioning between the three study groups, and there were no significant differences between the groups in bizarre behavior, delusions, hallucinations, thought disorder, or severity of depression (as measured by MADRS). These findings suggest that patients in the study groups have similar symptoms, yet the systematic differences in diagnostic patterns suggest either variation in symptom detection or in attributing importance to these symptoms. This raises questions about the influences of the interaction between the interviewee and interviewer.

Several other studies support our findings regarding possible underdetection of bipolar disorder among bilingual Latinos and suggest the possibility of atypical patient presentations. A study using administrative data suggested that there is an influence of language spoken, because Spanish speakers were diagnosed with less mania and more depression ( 12 ). Another study evaluated a group of Latino adolescents treated in an inpatient unit who were diagnosed as having major depressive disorder and were subsequently evaluated by a psychiatrist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV ( 13 ). Seventeen (52%) of the girls and ten (63%) of the boys met the DSM-IV criteria for bipolar disorder. Of those diagnosed as having bipolar disorder, 44% had bipolar II disorder and 57% had bipolar I disorder, 74% had mixed states, and 41% were psychotic (not mutually exclusive categories). Euphoric mania was virtually absent in this population. Concurrent aggressiveness and depression should alert clinicians to evaluate bipolarity, especially mixed states. Such activated-hostile depressive (or manic) mixed states may in part underlie some social deviance among these patients ( 13 ). Other studies suggesting atypical presentations of bipolar disorders have not considered the effect of ethnicity ( 14 ).

Different cognitive process models have been suggested to explain diagnostic discrepancies affecting ethnic minority groups. Important insights may accrue using structured clinical interviews to assess how and when the decision-making process may be flawed or where cognitive shifts are made by clinicians in considering one diagnosis over another. Although clinical experience and routine training in structured clinical interviews may mitigate cognitive biases associated with clinician judgment, they do not address cultural biases in the diagnostic system overall, because clinicians of different ethnic backgrounds or clinical training may tend to interpret the same patient information differently ( 15 ). Another factor is that very few cultural referents are available in the diagnostic instruments for affective and personality disorders.

There are limitations to our study design. The raters were not blinded to the ethnicity of the respondents. A higher likelihood of somatic presentations of depression among bilingual Latinos may have prompted them to seek treatment. The mean level of functioning for bilingual Latinos, as measured by the GAF, was slightly higher but comparable to the other two groups. It is possible that Latinos with more severe psychiatric and disabling disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are not seeking clinical help for reasons not explored in this study. This also suggests that an association of race, ethnicity, and symptom reporting should be clarified within ethnic Latino samples that are typically composed of a multirace ethnic population.

Our sample encompassed only English-speaking and bilingual study groups. Because of the small sample, analyses by nationality could not be performed. The sample had medium to high levels of acculturation, assuming that ability to speak English is a sign of acculturation. This limits the generalizability of findings reported here. Future studies need to recruit a group of Spanish-speaking Latinos with greater variance in acculturation. Without this comparison it is difficult to fully understand how language and culture independently influence the diagnostic process. We also did not assess language fluency but relied upon participant report regarding language skill.

Conclusions

This study used structured interviews and confirms disparate rates of diagnoses among bilingual Latino patients, compared with Euro-American patients, when both groups were interviewed in English. Compared with Euro-Americans, bilingual Latinos had significantly lower scores on the YMRS (indicating lower levels of mania) and were more likely to be diagnosed as having major depression. Monolingual English-speaking Latinos did not show this difference, suggesting a role of language in the diagnostic assessment. Moreover, this finding contrasts with several U.S. population (epidemiologic) studies that consistently show that Latinos whose predominant language is English have higher rates of mood disorders than Euro-Americans. The higher rates of major depressive diagnosis and lower levels of mania that we found among bilingual Latinos are similar to the findings of other studies and support the importance of language as a factor influencing processes of psychiatric diagnosis and the need to consider variant bipolar presentations among Latinos.

In summary, language of the interviewee and interviewer appears to have a major influence on symptom reporting. This potentially adverse influence on diagnosis and subsequent treatment requires further research.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The study was supported by grant R01-MH068801 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors thank all the mental health professionals and administrators who facilitated our study in the participating sites. The authors also thank William Lawson, M.D., and Quinton Moss, M.D., for their contributions to the study. Dr. Diaz was an active researcher on this project at UMDNJ-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School before returning to Yale University in the later stages of data collection.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Minsky S, Vega W, Miskimen T, et al: Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:637–644, 2003Google Scholar

2. Murray CJ, Lopez AD: The Global Burden of Disease. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1996Google Scholar

3. Vega WA, Karno M, Alegría M, et al: Research issues for improving treatment of US Hispanics with persistent mental disorders. Psychiatric Services 58:385–394, 2007Google Scholar

4. Vega WA, Sribney WM, Miskimen TM, et al: Putative psychotic symptoms in the Mexican American population: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 194:471–477, 2006Google Scholar

5. Pasternak MA, Zimmerman M: Elevated rates of psychosis among treatment-seeking Hispanic patients with major depression. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 193:66–69, 2005Google Scholar

6. Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, et al: Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:771–778, 1998Google Scholar

7. Del Castillo JC: The influence of language upon symptomatology in foreign-born patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 127:160, 1970Google Scholar

8. Price C, Cuellar I: Effect of language and related variables on the expression of psychopathology in Mexican American psychiatric patients. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 3:145–160, 1981Google Scholar

9. Marcos LR, Alpert M, Urcuyo L, et al: The effect of interview language on the evaluation of psychopathology in Spanish-American schizophrenic patients. American Journal of Psychiatry 130:549–553, 1973Google Scholar

10. Malgady RG, Costantino G: Symptom severity in bilingual Hispanics as a function of clinician ethnicity and language of interview. Psychological Assessment 2:120–127, 1998Google Scholar

11. Zayas LH, Cabassa LJ, Perez M, et al: Using interpreters in diagnostic research and practice: pilot results and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 68:924–928, 2007Google Scholar

12. Folsom DP, Gilmer T, Barrio C, et al: A longitudinal study of the use of mental health services by persons with serious mental illness: do Spanish-speaking Latinos differ from English-speaking Latinos and Caucasians? American Journal of Psychiatry 164:1173–1180, 2007Google Scholar

13. Dilsaver SC, Akiskal HS: High rate of unrecognized bipolar mixed states among destitute Hispanic adolescents referred for "major depressive disorder." Journal of Affective Disorders 84:179–186, 2005Google Scholar

14. Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al: Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 64:543–552, 2007Google Scholar

15. Whaley AL, Geller PA: Toward a cognitive process model of ethnic/racial biases in clinical judgment. Review of General Psychology 11:75–96, 2007Google Scholar