Service Use and Outcomes Among Elderly Persons With Low Incomes Being Treated for Depression

Elderly persons with low incomes are exposed to several risk factors for depression, such as living in deteriorated neighborhoods and having unstable housing, increased exposure to crime and victimization, poor nutrition, and poor physical health ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ). The rate of major depression is as high as 9% among elderly persons with low incomes, and they have more depressive symptoms than older adults who are not poor ( 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ).

Unfortunately, elders with low income are less likely to use mental health services than those with higher incomes ( 9 ). They face a number of practical barriers, including cost and transportation, in addition to other common barriers of stigma and lack of knowledge. In addition, two recent studies suggest that low-income elders do not respond as well to cognitive-behavioral therapy or antidepressant medication when treatment is offered alone ( 10 ) as they do when treatment is provided in the context of care management ( 11 ).

Collaborative care for depression in the primary care setting has been found to improve depression treatment utilization ( 12 ) and outcomes ( 13 ) for older adults. By providing treatment in primary care, this type of intervention may enhance use of services among older adults with low incomes. It also may enhance treatment outcomes for this population, providing a flexible approach tailored to an individual's needs and enabling collaboration with the primary care physician and other team members, who could address a variety of factors contributing to the individual's mood. Alternatively, low-income elders may find it difficult to attend appointments in the primary care setting and may require other types of interventions to reduce their unique stressors, such as linkage to transportation, meal services, and housing.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether collaborative care can improve use of depression treatment and its effectiveness among older adults with low incomes as well as among higher-income elders. We hypothesized that collaborative care would result in greater use of antidepressants or counseling, greater satisfaction, and better clinical outcomes (depressive symptoms and functional impairment) than usual care among low-income participants but that the effects would not be as strong as those for higher-income participants. We also examined pretreatment service utilization by income level, predicting less use by low-income participants.

Methods

The data for this study came from IMPACT (Improving Mood-Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment), in which 1,801 older primary care patients with depression (major depressive disorder or dysthymia) were randomly assigned to receive collaborative care or usual care in 18 primary care clinics across the United States. The study methods and primary intervention outcomes have previously been described ( 13 ) and will be presented briefly here. All procedures were approved by each organization's institutional review board, and all participants gave informed consent.

Sample

Participants were recruited from 18 primary care clinics belonging to eight health care organizations across five states. They were at least 60 years old, spoke English, and met criteria for major depression or dysthymia according to the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) ( 14 ).

Treatment conditions

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions, collaborative care or usual care. In collaborative care, depression treatment was managed by a team of providers, including the patient's primary care physician, a consulting psychiatrist, and a depression care specialist—a nurse or a psychologist working in the patient's regular primary care clinic who was available to patients assigned to collaborative care for up to one year. The depression care specialist assessed patients' depression, provided education about depression and treatment options, coordinated treatment, and coordinated services with the rest of the primary care team.

Participants in collaborative care were encouraged to choose between antidepressant medication and problem-solving therapy for primary care (up to eight 30-minute sessions of a structured behavioral intervention), which was delivered by the care specialist in primary care. The depression care specialist followed a stepped-care approach, regularly evaluating outcomes of treatment and facilitating changes in treatment according to a stepped-care protocol and in consultation with the primary care physician and consulting psychiatrist. In usual care, the primary care physician was informed of the individual's depression status and the individual was provided care as usual; no services were withheld in usual care, and patients could self-refer or be referred to specialty mental health treatments by their primary care providers.

Survey procedures

Data included in the current analyses were from baseline and three-, six-, and 12-month follow-up surveys. Before randomization, trained interviewers collected baseline data using a computer-assisted personal interview. A telephone survey research group then conducted blind follow-up interviews at three, six, and 12 months. Participants were recruited from July 1999 through August 2001.

Baseline and outcome assessment

At the baseline assessment, we collected information on sociodemographic characteristics and DSM-IV diagnoses of major depression or dysthymia by use of the SCID ( 14 ). Depression severity was measured with the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20 ( 15 ) (SCL-20); possible scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating worse depression. The SCL-20 is a self-report scale that has been used in a number of other depression quality improvement studies ( 16 ). Functional impairment was measured by self-rated general health (range 1–5, with lower scores indicating better health) and the 12-item Short Form Health Survey physical functioning scale ( 17 ) (PCS-12) (range 0–100, with higher scores indicating better functioning). We also administered the Cornell Service Use Index ( 18 ) to collect data on depression-related service use in the three months before study entry.

Outcomes of interest for this study were use of any depression treatment, defined as use of antidepressant medications or counseling or psychotherapy (yes or no); satisfaction with depression care, as indicated by the percentage of people who responded excellent or very good (compared with responses of poor, fair, or good); depressive symptoms, as measured by the SCL-20; and health-related functional impairment, as measured by general health self-ratings and the PCS-12.

Income definitions

Initially, we divided the sample into five income categories on the basis of the U.S. Census definitions and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) definitions of financial strain. According to the census criteria, poverty is defined as a household income of less than $12,000, regardless of region. Because some areas of the United States have higher costs of living than others, we decided to further delineate financial strain according to HUD criteria. HUD defines poverty levels on the basis of the median income levels of the region in which a person lives to adjust for area cost of living. According to HUD, persons living at or below 30% of the area median income (AMI) are considered "extremely poor," and those living at or below 50% of AMI are "very poor." For bivariate analyses, we divided the sample into five categories, poverty level (living at or below $12,000 a year); extremely strained (living between $12,000 and 30% of the AMI); very strained (living between 30% AMI and 50% AMI); strained (living between 50% and 75% of the AMI); and not strained (living at or above 75% of the AMI). For the primary analyses, we divided the sample into two groups, poor (living at or below 30% of the AMI) and not poor (living above 30% of the AMI).

Statistical methods

We used bivariate analyses to compare participants on baseline demographic and clinical variables according to their income status. Similar analyses were conducted to compare participants from the intervention and control groups stratified by income. In bivariate analyses, we used chi square tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables.

We used preplanned a priori contrasts to examine the differential intervention effects by income status. We conducted regression and logistic regression analyses through mixed-effects models using three-, six-, and 12-month follow-up data, specifying autoregressive covariance structure within subjects to account for within-subject correlation over time ( 19 ). Outcomes of interest were use of any depression treatment, satisfaction with depression treatment, depressive symptoms, and physical health. The primary predictor was income status: poor or not poor. Time was treated as categorical, and effects of time, treatment, and income and their interactions were examined. Covariates included the baseline measure for the outcome plus age, gender, ethnic minority group, education, marital status, number of comorbid chronic medical disorders, major depression (versus dysthymia), cognitive impairment, two or more prior episodes of depression, overall functional impairment, recruitment method (screening versus referral), and study site.

To test intervention effects within each income group at each time point (months 3, 6, and 12), we conducted pairwise two-sided t tests for comparing the intervention versus usual care by income status from the mixed-effects models. Adjusted group differences for continuously scaled variables and odds ratios for dichotomous variables are presented to illustrate effect sizes. Because of multiple comparisons, we used a conservative p value of <.01 to detect statistically significant differences. All analyses were conducted with SAS software, version 9.

Multiple imputations were used for missing data ( 20 , 21 , 22 ). We imputed five data sets, averaged predictions, and adjusted standard errors for uncertainty resulting from imputation ( 23 ). During the 12-month study, 69 patients died. Their postdeath values were not imputed, although the nesting of participants within treatment groups in the mixed-effects model allowed the inclusion of these patients with effects estimated only for the predeath data points ( 19 ).

Results

Baseline sample description

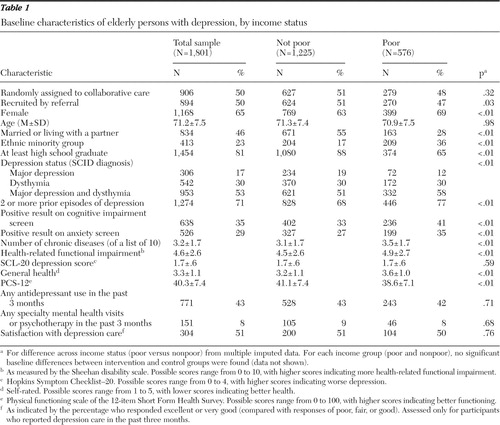

Table 1 presents data on characteristics of the 1,801 patients in the sample by income status (poor and not poor). Poor participants were more likely to be recruited via screening than referral, more likely to be from an ethnic minority group, and more likely to be women, single, and less educated. At baseline, poor participants had worse mental health and overall health, as indicated by their greater likelihood of having both dysthymia and major depressive disorder, two or more prior depression episodes, more psychiatric comorbidity (anxiety and cognitive impairment), more functional impairment, and worse overall health. No differences were found in use of or satisfaction with depression treatment in the three months before the study period. Within each income group, we found no significant differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the intervention and control groups.

|

Process of care

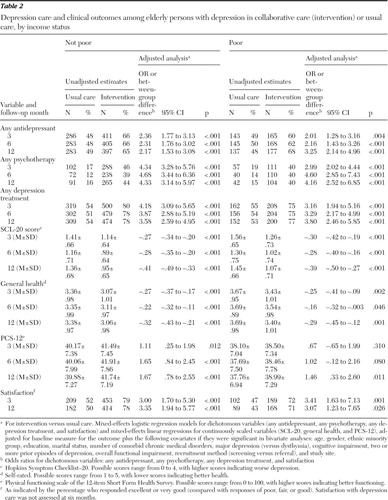

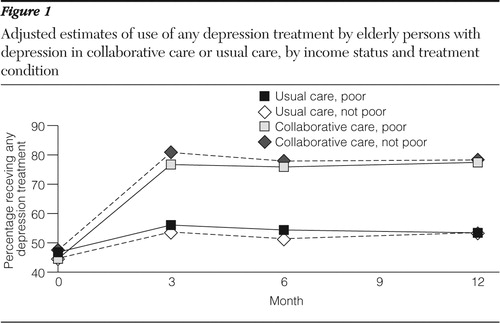

Service utilization. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1 , income status did not predict use of depression treatment (antidepressants or counseling) during the study period, nor did it interact with treatment condition and time to predict service use in mixed-effects models. Both poor and nonpoor participants had much greater service use at three, six, and 12 months in collaborative care than in usual care (p<.001). By 12 months, 200 of the poor participants in collaborative care (77%) had received depression treatment, compared with 152 of poor participants in usual care (53%) (odds ratio [OR]=3.80).

|

Bivariate analyses comparing intervention effects within income groups further supported the multivariate analyses that poor participants received better care in collaborative care than in usual care. Overall, the magnitude of intervention effects on processes of care was similar across the five income groups, and we did not observe a statistically significant interaction between intervention status and income group in mixed-effects models.

Satisfaction. As Table 2 shows, findings for satisfaction followed the same pattern, with no main effect of income status or any interactions involving income status with treatment condition or time in mixed-effects models. Poor participants were much more satisfied in collaborative care than in usual care (p=.001 at three months; p=.026 at 12 months). At three months, 189 poor participants in collaborative care (72%) were satisfied compared with less than half of poor participants in usual care—102 participants (47%) (OR=3.41).

Clinical outcomes

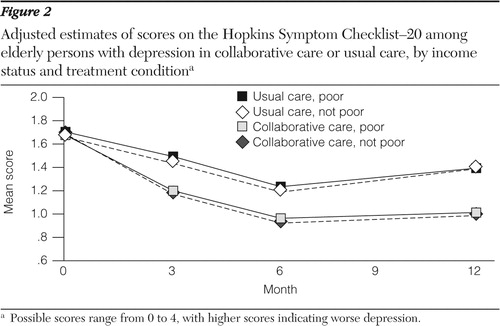

Depressive symptoms. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2 , mixed-effects models of SCL-20 scores showed no difference by income status, nor was there a differential response by treatment condition and income status. Both poor and nonpoor participants improved more with collaborative care than with usual care. As early as three months, poor participants in collaborative care experienced greater depressive symptom relief than poor participants in usual care; these gains were sustained at six and 12 months (p<.001).

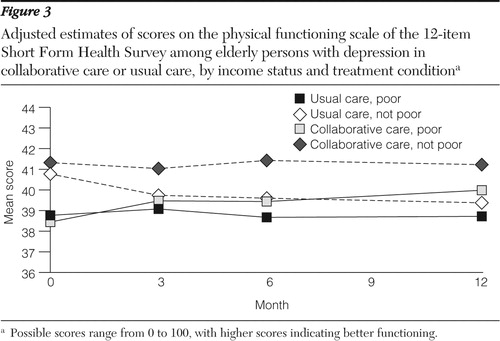

Functioning. Two functioning outcomes were examined: general health and physical functioning as measured by the PCS-12. As shown in Table 2 , in mixed-effects models for both outcomes, no main effect or interaction involving income status was found, with the exception of the PCS-12, for which a main effect was found at six months for income in the collaborative care group (t=–2.26, df=1, p=.025). General health was better for poor participants in collaborative care than for poor participants in usual care at all follow-up time points (p=.002 at three months, p=.046 at six months, and p<.001 at 12 months).

However, in stratified analyses of PCS-12 scores within each income group, results suggested that poor participants did not benefit from collaborative care as early as nonpoor participants. As shown in Table 2 and Figure 3 , for nonpoor participants, treatment differences in PCS-12 scores were evident at three months (p=.012) and sustained at six months (p<.001) and 12 months (p<.001). For poor participants no significant difference was found in PCS-12 scores between collaborative and usual care at three months, with a marginal difference at six months (p=.080), and a significant difference at 12 months (p=.011). The differences in PCS-12 scores between collaborative and usual care were very small for both income groups. For example, at three months, the estimated group difference in PCS-12 scores was 1.11 for nonpoor participants and .67 for poor participants. For this 100-point scale, these differences likely are not clinically significant.

Discussion

Data from this study indicate that older adults with low incomes as well as those with higher incomes can benefit from depression treatment in primary care, provided the right supports for depression management are in place. As was found in a previous study ( 11 ), the combination of an effective treatment with care management appears to significantly augment treatment effectiveness. It also appears to significantly influence low-income older adults' experience with mental health services; not only do they improve considerably, but they are more satisfied with their overall quality of care. Therefore, although use of mental health care and treatment effects are compromised by concomitant financial strain ( 9 , 10 ), when older poor patients are given support to best utilize depression treatment, their depression and disability improve significantly.

One consideration in depression management for poor older adults in primary care is the use of systematic screening. Poor elders in this study were somewhat more likely to be identified through screening than by referral from their primary care physician. This suggests that in the absence of a systematic screening procedure as part of a care management program, depression among older adults with low incomes may be overlooked. Also, although elderly persons with low incomes eventually experienced improvement in physical functioning, this improvement took longer than is typical for middle- and higher-income people, which suggests that low-income older adults need support for their depression management for at least one year in order to experience the full benefit of treatment. This slowed response could be a function of the significantly worse health of elderly persons with low incomes. Thus, although depressive affect may respond readily, physical functioning is compromised by the significantly poorer health of this population.

It is important to note that although the data presented here are compelling with regard to the treatment of elderly persons with low incomes, this study was not primarily designed to determine the effects of collaborative care in this population. Thus the findings should be viewed as preliminary. Participants were not stratified or identified specifically in terms of their degree of financial strain. Although the large sample theoretically ensures an equal distribution across conditions, as was borne out in the preliminary data analysis, the fact that these were volunteer participants may subject the data to some selection bias: those who participate in research may not be as financially strained or as depressed as those who do not. As reported previously ( 13 ), 86% of eligible, screened individuals enrolled in the study and dropout was low (8%), suggesting that collaborative care was successful in engaging the vast majority of depressed, older primary care patients. Nonetheless, 5% of those initially screened were ineligible for logistic reasons, such as lack of transportation or a telephone ( 13 ), so additional efforts likely are needed to engage elders with very low incomes who do not have these basic services.

Whereas this study revealed some important issues with regard to depression and functional outcomes, we were unable to determine whether collaborative care was able to effectively address other aspects of social adversity typically experienced by this population, such as unstable housing, irregular availability of food, and instability in other basic needs, and the degree to which resolution of problems in these areas mediates depression outcomes. Although the care managers who worked with the participants with lower incomes indicated that the work was more similar to case management services (acquiring transportation, stable housing, and referrals to social services), we did not document the differences in care that was provided by care managers of poor patients and care managers of elderly participants with more resources. Thus we were not able to address functional questions with regard to effective collaborative care for poor patients. These are very important questions to address in future research with older, low-income populations.

Also, the nature and clinical significance of the primary outcome measure, the SCL-20, should be considered. It is a self-report measure, although it has good reliability and validity and has been used in several other studies of depression quality improvement ( 16 ). Although SCL-20 scores improved more for participants in collaborative care, rates of response or remission on the SCL-20 were less than 50%. Thus, although low-income elders seemed to respond as well as higher-income elders, research still needs to be done to further improve depression treatment outcomes for all elders.

Conclusions

Despite limitations in the data, this study has important clinical implications regarding the management of depression among older patients with low incomes. First, contrary to the study by Cohen and colleagues ( 10 ), in which older, low-income elderly persons in clinical trials for late-life depression did not experience as much benefit from antidepressant medications, we found that depression treatment was effective and thus should be offered to low-income populations. However, these data further suggest that the combination of ongoing care management for at least a year is warranted to realize physical health benefits.

The data further suggest that integration of depression treatment into primary care significantly improves use of depression care by low-income elders. As was found in the study by Crystal and associates ( 9 ), poor elderly persons are often underrepresented in mental health care. Our study suggests that overcoming this particular access barrier by providing systematic depression screening and treatment in primary care is highly desirable.

Finally, this study has important implications for future research. More work is needed to better understand the processes by which depression treatment works for elderly persons with low incomes. It appears clear from the emerging data that depression treatment alone may not be sufficient to treat depression in low-income populations but that the combination of active treatment and care management in primary care may help overcome barriers faced by the low-income elderly population.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grants from the John A. Hartford Foundation, the California Healthcare Foundation, the Hogg Foundation, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The work was supported in part with patients, resources, and the use of facilities of the South Texas Veterans Health Care System and the Central Texas Veterans Health Care System. The IMPACT Investigators include (in alphabetical order): Patricia Areán, Ph.D. (co-principal investigator), Thomas R. Belin, Ph.D., Noreen Bumby, D.O., Christopher Callahan, M.D. (principal investigator), Paul Ciechanowski, M.D., M.P.H., Ian Cook, M.D., Jeffrey Cordes, M.D., Steven R. Counsell, M.D., Richard Della Penna, M.D. (co-principal investigator), Jeanne Dickens, M.D., Michael Getzell, M.D., Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., Lydia Grypma, M.D. (co-principal investigator), Linda Harpole, M.D., M.P.H. (principal investigator), Mark Hegel, Ph.D., Hugh Hendrie, M.B., Ch.B., D.Sc. (co-principal investigator), Polly Hitchcock Noël, Ph.D. (co-principal investigator), Marc Hoffing, M.D., M.P.H. (principal investigator), Enid M. Hunkeler, M.A. (principal investigator), Wayne Katon, M.D. (principal investigator), Kurt Kroenke M.D., Stuart Levine, M.D., M.H.A. (co-principal investigator), Elizabeth H. B. Lin, M.D., M.P.H. (co-principal investigator), Tonya Marmon, M.S., Eugene Oddone, M.D., M.H.Sc. (co-principal investigator), Sabine Oishi, M.S.P.H., R. Jerome Rauch, M.D., Michael Sands, M.D., Michael Schoenbaum, Ph.D., Rik Smith, M.D., David C. Steffens, M.D., M.H.S., Christopher A. Steinmetz, M.D., Lingqi Tang, Ph.D., Iva Timmerman, M.D., Jürgen Unützer, M.D., M.P.H. (principal investigator), John W. Williams Jr., M.D., M.H.S. (principal investigator), Jason Worchel, M.D., and Mark Zweifach, M.D. The authors also acknowledge the contributions and support of patients, primary care providers, and staff at the study coordinating center and at all participating study sites, which include: Duke University, Durham, North Carolina; South Texas Veterans Health Care System; Central Texas Veterans Health Care System; the San Antonio Preventive and Diagnostic Medicine Clinic; Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis; Health and Hospital Corporation of Marion County, Indiana; Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound in cooperation with the University of Washington, Seattle; Kaiser Permanente of Northern California, Oakland, and Hayward; Kaiser Permanente of Southern California, San Diego; and Desert Medical Group, Palm Springs, California. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the IMPACT study advisory board (Lydia Lewis, Lisa Goodale, A.C.S.W., Richard C. Birkel, Ph.D., Howard H. Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., Thomas Oxman, M.D., Lisa Rubenstein, M.D., M.S.P.H., Cathy Sherbourne, Ph.D., and Kenneth Wells, M.D., M.P.H.). The authors thank Tonya Marmon, M.S., for programming support. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Krause N: Chronic financial strain, social support, and depressive symptoms among older adults. Psychology and Aging 2:185–192, 1987Google Scholar

2. Krause N: Neighborhood deterioration and social isolation in later life. International Journal of Aging and Human Development 36:9–38, 1993Google Scholar

3. Angel RJ, Frisco M, Angel JL, et al: Financial strain and health among elderly Mexican-origin individuals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:536–551, 2003Google Scholar

4. Ostir GV, Eschbach K, Markides KS, et al: Neighbourhood composition and depressive symptoms among older Mexican Americans. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57:987–992, 2003Google Scholar

5. Areán PA, Alvidrez J: The prevalence of psychiatric disorders and subsyndromal mental illness in low-income, medically ill elderly. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 31:9–24, 2001Google Scholar

6. Krause N, Jay G, Liang J: Financial strain and psychological well-being among the American and Japanese elderly. Psychology and Aging 6:170–181, 1991Google Scholar

7. Rothermund K, Brandtstaedter J: Depression in later life: cross-sequential patterns and possible determinants. Psychology and Aging 18:80–90, 2003Google Scholar

8. Pinquart M, Sorensen S: Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging 15:187–224, 2000Google Scholar

9. Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, et al: Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly Medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 51:1718–1728, 2003Google Scholar

10. Cohen A, Houck PR, Szanto K, et al: Social inequalities in response to antidepressant treatment in older adults. Archives of General Psychiatry 63:50–56, 2006Google Scholar

11. Areán PA, Gum A, McCulloch CE, et al: Treatment of depression in low income, elderly primary care patients. Psychology and Aging 20:601–609, 2005Google Scholar

12. Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al: Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. American Journal of Psychiatry 161:1455–1462, 2004Google Scholar

13. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al: Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 288:2836–2845, 2002Google Scholar

14. First MB, Spitzer RL, Miriam G, et al: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research, 2002Google Scholar

15. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 9:13–28, 1973Google Scholar

16. Katon WJ, Robinson P, Von Korff M, et al: A multifaceted intervention to improve treatment of depression in primary care. Archives of General Psychiatry 53:924–932, 1996Google Scholar

17. Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD: A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34:220–233, 1996Google Scholar

18. Sirey JA, Meyers BS, Teresi JA, et al: The Cornell Service Index as a measure of health service use. Psychiatric Services 56:1564–1569, 2005Google Scholar

19. Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, et al: SAS System for Mixed Models. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 1996Google Scholar

20. Lavori PW, Dawson R, Shera D: A multiple imputation strategy for clinical trials with truncation of patient data. Statistics in Medicine 14:1913–1925, 1995Google Scholar

21. Little RJ: Missing data adjustments in large surveys. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 6:287–301, 1988Google Scholar

22. Tang L, Song J, Belin TR, et al: A comparison of imputation methods in a longitudinal randomized clinical trial. Statistics in Medicine 24:2111–2128, 2005Google Scholar

23. Rubin DB: Multiple Imputation for Non-Response in Surveys. New York, Wiley, 1987Google Scholar