Impact of Splitting Risperidone Tablets on Medication Adherence and on Clinical Outcomes for Patients With Schizophrenia

Tablet splitting can reduce the cost of drugs for patients, health care systems, and insurers who pay for prescription medications. Pharmaceutical companies commonly charge similar prices for different strengths of a given medication. As a result, the cost of many medications can be cut by as much as half if patients split tablets and take one-half of a high-dose formulation, rather than taking whole tablets of a low-dose formulation. Some payers, including federally financed health care systems and managed care companies, recognize that tablet splitting can reduce direct medication costs and have begun to recommend or even require that tablet splitting be used for certain medications ( 1 ).

However, few studies have examined the safety and clinical impact of tablet splitting. In 2000, a short report on tablet splitting from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Technology Assessment Program (TAP) concluded that "the published literature is limited with respect to both volume and quality of individual patient-based studies directly addressing the assessment question" and that the "TAP was unable to identify published studies that directly document increased risks or decreased safety associated with splitting drug tablets" ( 2 ). This situation has changed little in the intervening years.

Most studies of tablet splitting thus far have focused on its potential to reduce medication costs. Agents often cited as having considerable potential for cost savings include antidepressant drugs and lipid-lowering agents ( 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ). However, Donoghue ( 9 ) questioned whether tablet splitting would result in cost savings over the long term and predicted changes in the price structure of medication should pill splitting become widespread. Other studies of tablet splitting have assessed the mechanics and accuracy of splitting by measuring variation in tablet weights after splitting by pharmacists, trainees ( 10 , 11 , 12 ), or patients ( 13 , 14 ).

Few studies have measured the impact of tablet splitting on clinical outcomes. As with outcome studies in general, it is easiest to measure outcomes that are readily quantified. Several studies have suggested that splitting lipid-lowering agents has minimal impact on serum lipid levels ( 7 , 15 ). Unfortunately, mental health outcomes are not as easy to quantify as lipid levels, and literature is sparse on the impact of tablet splitting for individuals who are prescribed psychotropic medications. This population presents special concerns, particularly among individuals with severe mental illness and others who have symptoms of cognitive impairment that may interfere with their ability to understand and carry out tablet-splitting instructions. Nonetheless, because of their expense, psychotropic medications have been identified as prime targets for tablet-splitting programs ( 3 , 6 , 16 ).

The New York-New Jersey region of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Pharmacy Benefit Management program, following the lead of many other regions in VHA, recommended tablet splitting for the second-generation antipsychotic risperidone as a cost-savings measure. Risperidone was chosen because tablets are scored and relatively easy to split, and the cost of tablets containing higher-milligram doses is similar to the cost of lower-dose tablets. The study reported here began as a quality assurance study examining the clinical impact, if any, of the risperidone tablet-splitting program. The aims of the study were to determine whether, for patients with schizophrenia or related disorders, the risperidone tablet-splitting program was associated with changes in medication adherence, service utilization, or clinical outcomes. To our knowledge, there are no published studies that examined the clinical implications of tablet splitting for an antipsychotic medication.

Methods

Design

The study was a retrospective analysis of administrative data from the New York-New Jersey region of the VHA, which includes sites in New York City and its metropolitan area. We obtained institutional review board approval from each VA medical center in the New York-New Jersey region (Veterans Integrated Service Network 3).

Study population

We extracted data for all patients who received prescriptions for risperidone during the period January 2001 through March 2003 in the New York-New Jersey region of the VHA. Because we were interested in the impact of tablet splitting for individuals with schizophrenia who, in addition to psychosis, often have cognitive symptoms that could interfere with their ability to carry out splitting instructions, we limited analyses to individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (based on clinical diagnoses in the administrative database). We excluded patients treated at one of the five sites because the site did not implement tablet splitting until the final month of the study period. We restricted the sample to individuals who were prescribed risperidone and were actively engaged in outpatient treatment, defined as having received at least one prescription for risperidone other than at hospital discharge; being active in treatment for at least 90 outpatient days, demonstrated by outpatient service activity or receipt of an outpatient prescription for an antipsychotic medication during the study period; and having attended at least one scheduled mental health appointment during the study period.

We extracted data, including demographic characteristics, outpatient antipsychotic prescriptions, and service utilization for all inpatient stays and for outpatient mental health visits from the relevant local VA administrative databases. Because VA administrative data on race and ethnicity are often missing or incomplete, we do not report them in this study. For prescription data, we used prescriptions "released"—prescriptions that patients actually picked up at the pharmacy or that were mailed to them. We extracted data on 2,436 individuals with schizophrenia (including schizoaffective disorder) who were prescribed risperidone during the study period. A total of 2,130 individuals met minimum treatment criteria (attended at least one scheduled mental health appointment, received at least one prescription for risperidone other than at hospital discharge, and were active in outpatient treatment for at least 90 days). We excluded data from 252 individuals who sought care from the site that did not implement tablet splitting until the final month of the study. The final sample was 1,878 patients.

We categorized patients as "splitters" if they received at least one prescription for risperidone with an instruction to split tablets and had more than seven days' supply for their prescription. Splitting was identified using the "sig" field in the prescription data. Prescriptions for "one-half," "½," or ".5" tablets were flagged as splitting prescriptions. All other patients were considered "nonsplitters."

Measures

Medication adherence. We calculated medication possession ratios (MPRs) to measure medication adherence. The MPR is calculated by dividing the number of days' supply of antipsychotic medication actually dispensed by the number of days the patient is expected to be taking medication. An MPR of 1.0 indicated that, on average, the patient refilled medications on time, an MPR less than 1.0 indicated that the patient refilled medications less frequently than would be necessary to take the medication as frequently as prescribed, and an MPR greater than 1.0 indicated that the patient received extra medication. In the VA setting, where patients receive virtually all medications from the VA pharmacy, the MPR is a good proxy for adherence ( 17 ).

We calculated the numerator for the MPR by totaling the number of days prescribed for each oral antipsychotic medication. When more than one antipsychotic medication was prescribed on a given day (plus or minus two days), the days were counted only once. We calculated the denominator for the MPR (total time expected to be covered by a prescription for antipsychotic medication) by using each patient's date of first antipsychotic prescription until 60 days after his or her last contact (either last outpatient appointment or last filled prescription), excluding VA inpatient and nursing home days. Sixty days was used as the cutoff because we did not want to artificially inflate MPRs by assuming perfect adherence for the 30 days after the last contact (usually a filled prescription), nor did we want to artificially reduce MPRs by assuming that denominators extended to the end of the period for individuals who ceased contact. The 60-day cutoff assumed an MPR of .5 for individuals whose last contact was a prescription. Sensitivity analyses with different cutoffs were conducted, and similar results were obtained.

For splitters, two MPRs were calculated: one for the period before splitting began (presplitting) and the other for the period starting with the first splitting prescription until the end of the denominator described above (postsplitting). The postsplitting period extended to the end of each patient's denominator regardless of whether the patient received subsequent nonsplitting prescriptions because we did not wish to exclude outcomes that may have occurred or persisted after tablet splitting was discontinued but were related to it. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to examine more proximal outcomes.

Outpatient service utilization patterns. We examined service utilization patterns as a measure of clinical stability. We calculated rates of scheduled, kept appointments and of unscheduled (walk-in) appointments per person per month. For each patient, we evaluated both the proportion of scheduled appointments that were kept and the ratio of unscheduled appointments to scheduled, kept appointments. Time in VA inpatient or nursing home care was subtracted from the denominator for these calculations. We used proportion of scheduled, kept appointments as a proxy for good clinical outcome because the measure suggests good adherence to outpatient treatment. A high ratio of unscheduled to scheduled, kept appointments suggests that scheduled appointments were insufficient to meet clinical developments or that intervening factors interfered with patients' ability to maintain scheduled contacts; therefore, this measure was a proxy for poor clinical outcomes.

Inpatient admission rates. We examined admission rates as a proxy measure for clinical outcomes. We calculated the psychiatric admission rate (number of admissions per patient-year) as a proxy for psychiatric relapse and used the nonpsychiatric admission rate (number of admissions per patient-year) as a measure of adverse medical outcomes. Time for admissions before prescription splitting was initiated included time from the first antipsychotic prescription to the first prescription for split tablets; time for admissions during the postsplitting period included time from the first splitting prescription until four months after the last prescription. We extended the denominator for inpatient admissions (as compared to the denominator for the MPR) in the postsplitting period in order to capture admissions that may have resulted from treatment nonadherence subsequent to splitting.

Data analyses

Baseline characteristics. To determine whether individuals with prescriptions for split tablets were a population distinct from those with prescriptions for whole tablets, we compared demographic characteristics (age and sex) for both groups. We examined service characteristics of the whole-tablet group and of the split-tablet group in the presplitting period. Service characteristics included MPR; rate of scheduled, kept appointments; rate of unscheduled appointments and proportion of appointments kept; ratio of unscheduled to scheduled, kept appointments; psychiatric admissions; nonpsychiatric admissions; and risperidone daily dosage. We used two-sample t tests for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon ranked-sum tests for nonparametric data.

Comparison of pre- and postsplitting. To examine whether tablet splitting was associated with changes in antipsychotic medication adherence or changes in service patterns, we compared measures of adherence (MPR) and service utilization (kept appointment rate, unscheduled appointment rate, proportion of appointments kept, ratio of unscheduled to scheduled and kept appointments, and psychiatric and nonpsychiatric admission rates) for the split-tablet group before and after splitting. To facilitate paired comparisons, only individuals with 60 or more outpatient days before initiating splitting and whose first tablet split occurred at least 60 days before the end of the study period were included in the paired analyses. We conducted paired t tests for normally distributed data and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for nonparametric data. We conducted regression analysis to examine the impact of age on outcomes.

Results

The mean±SD age for the study population was 51.6±11.6 years. Of the sample, 1,784 (95%) were male. Nonsplitters and splitters did not differ in age or gender distribution. Table 1 shows service characteristics of the population. The whole-tablet group and the split-tablet group before initiating splitting did not differ significantly in MPR, rate of kept appointments, proportion of kept appointments, psychiatric admission rate, or nonpsychiatric admission rate. The whole-tablet group received prescriptions for significantly higher doses of risperidone than the split-tablet group in the presplitting period (dose 4.11±2.29 mg per day versus 3.30±1.95 mg per day, p< .001). The whole-tablet group also had a higher rate of unscheduled appointments (.19 versus .09 per person per month, p<.001) and a higher ratio of unscheduled to scheduled, kept appointments (.25 versus .10, p<.001).

|

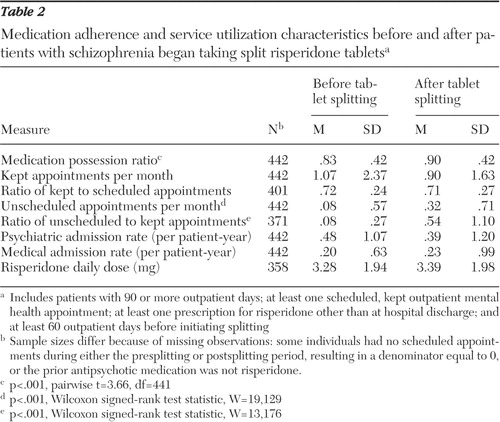

The MPR increased after initiating splitting ( Table 2 ). A comparison of the split-tablet group in the presplitting and postsplitting periods indicated that MPR increased from .83 to .90 (p<.001), monthly unscheduled appointments increased from .08 to .32 (p<.001), and the ratio of unscheduled to scheduled, kept appointments (calculated at the patient level) increased from .08 to .54 (p<.001). Monthly kept appointments and the proportion of scheduled, kept appointments did not change significantly. We detected no significant change in either psychiatric admission rates or general medical admission rates. Age had no significant impact on outcome measures.

|

To examine whether changes in service utilization patterns in the postsplitting period were temporary disruptions or more permanent changes, we examined results for two distinct postsplitting periods: 0 to 60 days and 61 to 120 days postsplitting (excluding patients whose first split-tablet prescription was less than 120 days before the end of the observation period). Both kept appointment rate and unscheduled appointment rate increased during the first 60 days after initiating splitting. During the subsequent 60 days the kept appointment rate returned to baseline, and the unscheduled appointment rate decreased nonsignificantly.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that introducing tablet splitting is followed by a modest increase in outpatient service utilization patterns but has no clear impact on clinical outcomes. Neither the psychiatric admission rate nor the nonpsychiatric admission rate increased among patients who were prescribed risperidone after initiating tablet splitting. The MPR increased after initiating splitting, as did the rate of unscheduled appointments and the ratio of unscheduled to scheduled, kept appointments. Although the MPR typically is taken as a measure of medication adherence, it seems unlikely that patients became significantly more adherent to medication after initiating splitting. What seems more likely is that patients either lost some tablets as a result of crumbling or other mechanical problems with splitting or misunderstood the splitting instructions and took whole tablets rather than half-tablets. Either is consistent with patients who required additional medication to be dispensed (reflected in the increased MPR). Alternatively, if patients had trouble with tablet splitting and became more symptomatic, they may have subsequently increased their dose either on their own or on a physician's instructions.

The increase in unscheduled visits observed after initiating splitting is consistent with individuals' returning to the clinic earlier than scheduled in order to obtain additional medication supplies. We did not detect a significant change in patients' attendance at scheduled mental health appointments after initiating tablet splitting. The changes in service utilization patterns were more pronounced in the first 60 days after initiating splitting than in the subsequent 60 days but did not return fully to baseline during days 61 to 120. The observed pattern suggests that these changes could have been related to initiating tablet splitting—involving either technical difficulties with splitting or problems communicating splitting instructions among the patient, physician, and pharmacy. Longer follow-up could help clarify whether the changes in outpatient service patterns represent a transient adjustment period or persistent difficulties.

The study had a naturalistic design and describes the impact of tablet splitting as it played out in a real-world setting. Our baseline data suggest that individuals who were prescribed split tablets were not substantially different from those prescribed whole tablets; however, the splitters received lower doses of risperidone and were also less likely to make unscheduled visits before initiating tablet splitting. Regardless, we were interested in the impact of splitting on patients who split tablets in actual practice, even if they had been a select population. The population studied was middle-aged, and individuals were in ongoing outpatient treatment. Our results may not be generalizable to a younger patient population, individuals earlier in the course in their illness (who might even perceive of tablet splitting as a step toward medication discontinuation), or those experiencing acute exacerbations of symptoms.

Oral risperidone is a relatively easy medication to split. The pills are scored, and tablets for different doses are different colors. Risperidone's long half-life minimizes the impact of minor dose variations that may occur as a result of inexact splitting. The impact of tablet splitting may be different for other medications with varied physical and pharmacokinetic properties.

Administrative data provide quantitative service utilization and prescription data for large groups of patients in real-world settings. However, a limitation of administrative data is that they do not provide explanatory information regarding individual motivations or interpersonal interactions. Future studies involving primary data collection or individual record review would be needed to establish the precise reasons for the increase in MPR and the increase in unscheduled visits. Likewise, primary data collection would be needed to determine who performed the tablet splitting (patients, family members, or others if pharmacists did not provide split tablets) and about the quality and consistency of education about tablet splitting that patients received from pharmacists.

Limitations of administrative data analysis also stem from the use of proxy measures available in the data set. For example, the MPR is based on prescriptions dispensed but does not necessarily reflect medication swallowed. Individuals may not take medications as prescribed, may take medications stored at home from previous prescriptions, or may take medications prescribed to other individuals. However, in the VA, the MPR has been shown to be a good proxy for adherence. We calculated MPRs based on prescriptions for any antipsychotic medication, assuming that patients with schizophrenia who are treated with antipsychotic medication generally receive ongoing antipsychotic medication treatment. However, this assumption may not be true in every case.

Furthermore, using administrative data, we found it difficult to calculate precise MPRs for individuals who were prescribed multiple antipsychotic medications simultaneously. By totaling days' supply for all antipsychotic medications in the numerator, except for those prescribed within two days of each other, we overestimated the actual MPR for individuals prescribed more than one antipsychotic simultaneously. However, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by restricting the sample to individuals exposed to two or fewer antipsychotic medications during the study period. We obtained similar results (except that the calculated MPRs were slightly lower when fewer drugs were included). We chose to include all activity after the first splitting prescription in the postsplitting denominators even if the individual resumed taking whole tablets or changed antipsychotic medications. We did so because we were interested in the impact of splitting in the course of routine practice, rather than the impact of splitting isolated from routine clinical decision making.

Using the proportion of scheduled, kept appointments as a proxy measure of good clinical outcomes may measure an individual's general adherence behavior and not necessarily be a consequence of splitting risperidone tablets. However, in the paired comparisons, individuals served as their own analytic controls, which should have controlled for their general adherence behavior.

Finally, it was beyond the scope of this study to examine cost data. Future studies are needed to examine whether cost savings achieved from tablet splitting were offset by increased rates of unscheduled appointments in the months after initiation of tablet splitting.

Conclusions

This study provided some assurance that prescribing tablet splitting for patients with schizophrenia who are treated with risperidone does not result in poor outcomes as measured by psychiatric and medical inpatient admissions. However, we observed an increase in the rate of unscheduled outpatient appointments and an increase in the amount medication dispensed compared with the amount that would be expected if patients successfully took half-tablets, particularly during the first 60 days after initiating tablet splitting. Increases in unscheduled appointments may burden service systems if prescriptions for tablet splitting are given to a large number of patients at once, without sufficient education and support. Patients who are prescribed tablet splitting should be instructed carefully about their medication regimen. Future studies should address longer-term clinical outcomes and systemwide costs.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by the Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center of Veterans Integrated Service Network 3 and the Targeted Research Enhancement Program at the Bronx Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

The authors report no competing interests.

1. Marino V: To make a pill more affordable, cut it in half. New York Times, Apr 13, 2004Google Scholar

2. VA Technology Assessment Program Short Report No 3—Tablet Splitting. Boston, Health Services Research and Development Management Decision and Research Center, May 2000Google Scholar

3. Dobscha SK, Anderson TA, Hoffman WF, et al: Strategies to decrease costs of prescribing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors at a VA medical center. Psychiatric Services 54:195-200, 2003Google Scholar

4. Vuchetich JP, Garis RI, Jorgensen AM: Evaluation of cost savings to a state Medicaid program following a sertraline tablet-splitting program. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 43:497-502, 2003Google Scholar

5. Cohen CI, Cohen SI: Potential savings from splitting newer antidepressant medications. CNS Drugs 16:359-360, 2002Google Scholar

6. Stafford RS, Radley DC: The potential of pill splitting to achieve cost savings. American Journal of Managed Care 8:706-712, 2002Google Scholar

7. Gee M, Hasson NK, Hahn T, et al: Effects of a tablet-splitting program in patients taking HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors: analysis of clinical effects, patient satisfaction, compliance, and cost avoidance. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 8:453-458, 2002Google Scholar

8. Bachynsky J, Wiens C, Melnychuk K: The practice of splitting tablets. Pharmacoeconomics 20:339-346, 2002Google Scholar

9. Donoghue J: Splitting antidepressant medications. CNS Drugs 16:359-360, 2002Google Scholar

10. Polli JE, Kim S, Martin BR: Weight uniformity of split tablets required by a Veterans Affairs policy. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy 9:401-407, 2003Google Scholar

11. Rosenberg JM, Nathan JP, Plakogiannis F: Weight variability of pharmacist-dispensed split tablets. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 42:200-205, 2002Google Scholar

12. Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, et al: Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association 42:195-199, 2002Google Scholar

13. Peek BT, Al-Achi A, Coombs SJ: Accuracy of tablet splitting by elderly patients. JAMA 288:451-452, 2002Google Scholar

14. Matuschka PR, Graves JB: Mean dose after splitting sertraline tablets. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62:826, 2001Google Scholar

15. Duncan MC, Castle SS, Streetman DS: Effect of tablet splitting on serum cholesterol concentrations. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 36:205-209, 2002Google Scholar

16. Cohen CI, Cohen SI: Potential cost savings from pill splitting of newer psychotropic medications. Psychiatric Services 51:527-529, 2000Google Scholar

17. Valenstein M, Copeland LA, Blow FC, et al: Pharmacy data identify poorly adherent patients with schizophrenia at increased risk for admission. Medical Care 8:630-639, 2002Google Scholar