Perceived Effectiveness of Medications Among Mental Health Service Users With and Without Alcohol Dependence

Substance use disorders often complicate the treatment of common mental disorders, such as depression and anxiety. Evidence from community-based studies, such as the National Comorbidity Survey ( 1 ) and the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions ( 2 ), suggests that about one of five individuals with a common mental disorder has a comorbid alcohol or drug use disorder.

There is little consensus about the etiology and effective treatment of mental disorders when the patient has a comorbid substance use disorder ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ). This lack of consensus is reflected in a paucity of guidelines specifically addressing the treatment of co-occurring disorders as indicated by a recent search of the National Guideline Clearinghouse ( 11 ). When guidelines for mental disorders address comorbid substance use disorders, the recommendations are brief and nonspecific. In the case of depression and anxiety, one or two paragraphs, or less, in medium-length papers and short monographs is typical ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ).

A key clinical question is whether, or when, to use psychiatric medications to treat the psychiatric symptoms of substance users. Guidelines addressing the use of psychiatric medications ( 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ) often, but not always, recommend a period of abstinence or detoxification before initiation. This uncertainty likely stems from the limited evidence base ( 24 ).

There are several rationales for the conservative nature of medication guidelines. First, psychiatric symptoms may be exacerbated by substance use and withdrawal and may improve with abstinence, even when the underlying psychiatric disorder is not substance induced ( 4 ). Second, although treatment of independent psychiatric disorders may be more easily justified, practical difficulties arise in distinguishing substance-induced from independent disorders in the context of clinical interviews without the ability to observe patients during periods of extended abstinence ( 27 ). Third, medications may be dangerous and hard to manage among active substance users, particularly certain medication classes, such as tricyclic antidepressants ( 27 , 28 ).

At the same time, a growing number of studies have investigated the effect of newer agents, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), for patients with depression or anxiety and co-occurring substance use disorders ( 24 , 29 ). SSRIs have the advantage of being safer in overdose and of having few contraindications. A recent meta-analysis investigated the efficacy of antidepressants for individuals with depression and current comorbid alcohol or other substance dependence, many of whom were actively using alcohol or drugs ( 29 ). This study and literature reviews suggest that antidepressant medications are moderately effective in improving depression symptoms but less effective in reducing substance use and sustaining abstinence ( 24 , 29 ). Other studies suggest that SSRIs can improve posttraumatic stress disorder and reduce anxiety symptoms among patients with co-occurring alcohol dependence ( 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ).

Similarly, no consensus exists regarding the use of benzodiazepines for patients with comorbid depression or anxiety and substance use disorders ( 24 ).

One study that investigated patterns of medication use among alcohol-dependent veterans found that those with alcohol dependence were slightly less likely in multivariate models to receive antidepressants ( 34 ), but little is known outside settings in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Further, little is known about the experiences of patients with co-occurring disorders who receive psychiatric medications outside clinical research settings. These research topics are important, given the discordance between clinical practice guidelines and recent clinical evidence suggesting the safety and moderate effectiveness of these medications for individuals with active substance use disorders.

This study sought to fill the gap in the literature by using a large, nationally representative survey to investigate the use and patient-perceived effectiveness of psychiatric medications among mental health care users with alcohol dependence. Despite growing interest in the use of pharmacotherapy to treat patients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, this paper is the first, to our knowledge, to address these topics from a population-based perspective. Although the effects of antidepressant medications on craving and consumption among alcohol-dependent individuals is an active area of inquiry ( 29 , 35 , 36 ), we focused on changes in psychiatric symptoms among alcohol-dependent individuals who reported using mental health care to treat "mental and emotional problems" and not for the explicit goal of reducing alcohol consumption.

Specifically, we investigated three hypotheses. First, among mental health care users, are patients with alcohol dependence less likely to receive psychiatric medications than those who are not alcohol dependent? Second, among alcohol-dependent mental health care users, is there a difference between medication users and nonusers in the perceived effectiveness of mental health care? Third, among medication users, is there a difference between alcohol-dependent patients and nondependent patients in the perceived effectiveness of mental health care?

Methods

Sample

We pooled data from three annual cross-sections (2001 to 2003) of the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to increase the statistical power to detect true differences across subgroups. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration conducts the NSDUH annually for the primary purpose of estimating the prevalence of illicit drug, alcohol, and tobacco use in the United States ( 37 , 38 ). The average annual response rate is 75 percent ( 38 , 39 ). The pooled sample included respondents aged 12 years and older

After the study was described in detail to the eligible participants, oral informed consent to continue the interview was obtained. Written consent was not obtained because the names of participants were not used in the screening and interview process in order to protect confidentiality. The survey takes roughly one hour to complete. To ensure confidentiality, questions about substance use, mental health problems, and treatment are completed though audio-assisted interview technology in which respondents key their responses directly into a laptop computer. Remaining questions are completed through a computer-assisted in-person interview. The survey is available at www.icpsr.umich.edu/samhda.

In the 2001 through 2003 surveys, the "adult mental health" module was administered to respondents aged 18 years and older. The module consists of screening questions about the presence and severity of mental health problems and questions about mental health care use in the past year. Because of our interest in patterns of mental health care use, we limited our analysis to the 11,872 adults who reported seeing "a doctor or mental health professional for any problem" with "emotions, nerves, or mental health" during the past 12 months. To control for unobserved differences across subgroups with substance use disorders, we sought to increase the homogeneity of our sample by excluding 480 mental health care users who were dependent on substances other than alcohol.

Dependent variables

Use of mental health medications. Respondents were asked, "During the past 12 months, did you take any prescribed medication that was prescribed for you to treat a mental or emotional condition?"

Self-reported effectiveness of mental health treatment. Respondents who had received mental health treatment in the past 12 months were asked, "You mentioned earlier in the interview that you saw a professional or received prescription medications for your emotional problems in the past 12 months. How much did the counseling or medications improve your ability to manage daily activities like those asked about in the previous questions?" The previous questions referred to activities such as taking care of daily responsibilities at work or school, taking care of household responsibilities, and participating in social activities. Responses were on a scale of 1 to 5 (1, none; 2, a little; 3, some; 4, a lot; and 5, a great deal).

Independent variables

Problem alcohol use. We used measures of both 12-month alcohol dependence and heavy drinking in the past 30 days. A respondent was considered to be alcohol dependent if he or she endorsed three or more of the DSM-IV alcohol dependence criteria. Heavy drinking was defined as five or more drinks on five more occasions in the past 30 days.

Mental health status. First, we used a clinically validated screen for serious mental illness in the past year ( 40 , 41 ). The screen is based on a measure of nonspecific psychological distress known as the K6. The K6 was developed for use in the National Health Interview Survey and subsequently included in the NSDUH. The indicator was developed to identify serious mental illness as defined in Public Law 102-321 as having at least one 12-month DSM-IV disorder (excluding substance disorders) along with "serious impairment." As a result, the measure is more inclusive than other measures of serious mental illness that rely on past use of mental health services or a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other forms of psychosis ( 42 , 43 ). Furthermore, because the measure is based on psychological distress, the symptoms most associated with prevalent anxiety and mood disorders, most individuals with serious mental illness on the K6 have depressive or anxiety disorders rather than psychosis.

The K6 includes six questions that measure on a scale of 0 to 4 how frequently respondents experienced symptoms of psychological distress (nervousness, hopelessness, restlessness, feeling depressed, feeling worthless, or feeling that everything is an effort) during the month in the past year when they were feeling their worst emotionally. Respondents with scores of 13 and higher based on a simple count of the endorsed items are considered to have serious mental illness ( 40 , 41 ).

Second, our multivariate analysis included a series of indicator variables to measure whether a respondent reported a symptom of a DSM-IV mental disorder in the 12 months before the interview on the basis of stem and summary symptom measures drawn from a truncated version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form ( 40 , 44 ). The mental health symptoms covered in the survey represent key constructs from the major disorders (major depressive disorder, mania, generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, social phobia, agoraphobia, and posttraumatic stress disorder). The criterion of having a DSM symptom, rather than actually meeting full DSM criteria, is a much broader definition of mental health problems, and thus rates of any DSM symptom are higher than estimated rates of DSM disorders in population surveys ( 2 , 45 ).

Other covariates

In addition to indicators of symptoms of disorders, our multivariate models included a wide range of covariates intended to control for confounding relationships between alcohol dependence and our dependent variables—use of psychiatric medications and self-reported effectiveness of mental health treatment. Covariates included past-month use of marijuana and other illicit drugs, past-year use of substance abuse treatment (both specialty-based treatment and participation in self-help groups), self-reported fair or poor health status, race or ethnicity (black, Hispanic, and other), age, gender, marital status (widowed, divorced or separated, and never married), household income of less than $20,000, graduation from college, insurance status, geographic region of the United States (Northeast, North Central, West, or South), rural residence, and indicators of the survey year.

Analyses

For each hypothesis the relevant analytic sample differed. For our three hypotheses, the samples were: mental health care users, alcohol-dependent mental health care users, and mental health care users who were using prescribed psychiatric medications. Each hypothesis was also tested in the relevant subgroup further limited to serious mental illness, as defined by the K6. For example, the second hypothesis was tested for both alcohol-dependent mental health care users and alcohol-dependent mental health care users with serious mental illness. We took this approach because we could be more confident that individuals with serious mental illness who were in mental health treatment were receiving treatment for their mental health problems and not for the primary purpose of treating their alcohol dependence.

All estimation procedures and statistical tests were implemented using the survey analysis commands in STATA 8.0 and adjusted for survey weights, clustering, and stratification. The p values correspond to two-sided t tests for dichotomous variables and to F statistics corresponding to adjusted Wald tests for multinomial variables.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows differences in psychiatric symptoms, substance use, and other covariates by alcohol dependence for all adult mental health care users and mental health care users with serious mental illness. Compared with mental health users without alcohol dependence, those with alcohol dependence generally had higher rates of psychiatric symptoms and higher rates of substance use, were younger, were less likely to be married and to be female, and more likely to have low household incomes, to be uninsured, and to live in rural areas.

|

a Not adjusted for covariates. Percentages are weighted.

Among respondents who had used mental health care in the past year, no statistically significant differences in the rate of psychiatric medication use were found between those with and without alcohol dependence (data not shown): 76.2 percent of respondents with alcohol dependence and 75.9 percent of those without dependence had used psychiatric medication in the past year. Similarly, among those with serious mental illness who had received mental health treatment, 81.9 percent of those with alcohol dependence and 85.0 percent of those without dependence had taken psychiatric medication in the past year.

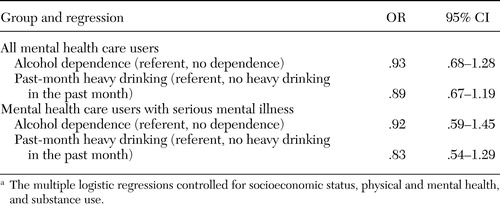

As shown in Table 2 , in multiple logistic regression models for respondents who had used mental health care, no significant differences were found between those with and without alcohol dependence in the odds of psychiatric medication use. Because we were concerned about the collinearity of 12-month alcohol dependence and heavy drinking in the past month, we also examined the joint significance of these two variables and found them to be nonsignificant predictors of psychiatric medication use in the sample of all mental health users and for mental health users with serious mental illness.

|

a The multiple logistic regressions controlled for socioeconomic status, physical and mental health, and substance use.

Perceived effectiveness of mental health treatment

As shown in Table 3 , among alcohol-dependent respondents who had used mental health care and who had taken psychiatric medication in the past year, 20 percent reported that mental health treatment helped a great deal, 34 percent reported that treatment helped a lot, and 25 percent reported treatment helped some. The corresponding figures for those who had not received psychiatric medications were significantly lower, 13 percent, 22 percent, and 29 percent, respectively.

|

a Treatment effectiveness was measured in terms of its ability to improve respondents management of daily activities. The analysis did not adjust for covariates. Percentages are weighted.

A similar pattern was seen among alcohol-dependent patients with serious mental illness ( Table 3 ). Respondents who had received psychiatric medication were more likely than those who had not received medication to report that treatment was effective. These differences were highly significant.

In a multiple logistic regression model of perceived effectiveness of treatment among alcohol-dependent respondents who had received mental health care, those who had received psychiatric medication were significantly more likely than those who had not to report that treatment helped a lot or a great deal (odds ratio [OR]=2.87, 95 percent confidence interval [CI]=1.57 to 5.26; t=3.42, df=510, p<.001). This pattern persisted when the sample was restricted to those with serious mental illness (OR=3.51, CI=1.62 to 7.59; t=3.21, df=447, p=.001).

As shown in Table 4 , among respondents who received psychiatric medication in the past year, 20 percent of those with alcohol dependence reported that mental health treatment helped a great deal, 34 percent reported it helped a lot, and 25 percent reported that it helped some. Among those who received psychiatric medication who were not alcohol dependent, 30 percent reported that mental health treatment helped a great deal, 34 percent reported it helped a lot, and 20 percent reported it helped some. The differences between those with and without dependence were significant. These patterns were similar but not statistically significant when we restricted the analyses to respondents who had serious mental illness, although rates of patient-reported effectiveness were somewhat lower among those with serious mental illness than among those without it.

|

a Treatment effectiveness was measured in terms of its ability to improve respondents management of daily activities. The analysis did not adjust for covariates. Percentages are weighted.

In multiple logistic regression models for individuals who received psychiatric medication, no statistically significant differences in patients' ratings of the effectiveness of mental health treatment were found between alcohol-dependent and nondependent respondents or between respondents who drank heavily in the past month and those who did not. Similarly, no statistically significant differences in perceived effectiveness were found when the analysis was limited to respondents with serious mental illness. Further, in joint tests of significance, alcohol dependence and heavy drinking in the past month were not significantly associated with patients' reports of effectiveness among all individuals in mental health treatment who had received psychiatric medication or among those with serious mental illness who had received treatment and medication.

Discussion

The results of our study offer a highly generalizable picture of medication use and patient-perceived effectiveness of treatment among alcohol-dependent patients that is not available from selected samples drawn from rosters of current patients, admission cohorts, health system enrollees, or research studies. We view the results of our study as an important complement to clinical studies of medication efficacy.

In the NHSDUH survey, a large majority of alcohol-dependent individuals in mental health treatment received some form of psychiatric medication, despite the lack of guideline support in this area. Furthermore, alcohol dependence or heavy drinking did not decrease the likelihood of receipt of psychiatric medication.

Among alcohol-dependent patients who used mental health care, those who received psychiatric medication were significantly more likely than those who did not to report that treatment was effective. The magnitude of the effect in adjusted models was large.

Among individuals who received psychiatric medication, those without alcohol dependence were more likely to report that treatment was helpful than those with alcohol dependence. However, no significant differences were found in adjusted models. Furthermore, among those who received psychiatric medication, a large majority of those with and without alcohol dependence reported that treatment was at least somewhat helpful. Possible reasons for the lower perceived effectiveness among alcohol-dependent patients include greater severity of illness, decreased adherence, or decreased medication efficacy in the context of ongoing alcohol dependence.

A key question is how our results on patient-perceived effectiveness of treatment should be interpreted. A conservative interpretation is that a large majority of individuals with alcohol dependence who receive psychiatric medication find such treatment acceptable and are satisfied with such care. A much more speculative interpretation suggested by the data in Table 4 is that medications for mental disorders are effective for psychiatric symptoms among persons with alcohol dependence, although perhaps not as effective as they are among nondependent individuals.

In this light, it is interesting to compare our results with those of recent reviews that have examined the effectiveness of depression treatment for patients with alcohol or drug use disorders who participated in clinical efficacy studies ( 29 ). (No similar literature exists for the effectiveness of treatment of anxiety disorders among patients with alcohol or drug disorders.) The similarity of findings is striking, given the vastly different methodologies. We found that about half of individuals with alcohol dependence who received a medication reported that mental health treatment helped a great deal or a lot. In a meta-analysis, Nunes and Levin ( 29 ) calculated that among more than 800 individuals with depression and comorbid alcohol or drug dependence, more than half (52 percent) who received antidepressants had a reduction in their depressive symptoms. They concluded that individuals with depression and comorbid substance use disorders have moderate responses to antidepressants—responses that are not as great as those of nondependent individuals. However, although Nunes and Levin found that individuals with substance dependence were somewhat less likely to respond to antidepressant treatment, we found no differences in reports of perceived effectiveness between those who were alcohol dependent and those who were not.

Although it is interesting to compare our estimates of perceived effectiveness to estimates of efficacy in clinical studies, it is important to recognize the limitations of such an approach. First, our study was observational, and patients were not randomly assigned to medication, which could create a selection bias. Unfortunately, it is difficult to definitively state the direction of the bias. Typically, we would expect that respondents with more severe mental health problems would be the most likely to receive psychiatric medications. The question then becomes, Would sicker individuals be more or less likely to report that treatment is effective? If sicker individuals are less likely to report that treatment is effective, then we might actually have underestimated patient-perceived effectiveness of antidepressants among individuals with alcohol dependence.

The NSDUH measures of mental health problems, alcohol dependence, and treatment use lack the rich clinical detail that is the hallmark of highly controlled, patient-based research. On the other hand, the focus of our effectiveness measure on daily functioning—"How much did the counseling or medications improve your ability to manage daily activities like those asked about in the previous questions?"—has a high degree of real-world significance. Thus our measure of effectiveness is an important complement to clinical measures, not a poor substitute.

One consequence of our lack of clinical detail is that we cannot positively say that medication use and alcohol dependence occurred simultaneously. Medication use could have actually taken place after a period of abstinence or before alcohol dependence developed. To guard against this problem, we used 12-month dependence and heavy drinking in the past 30 days in our models. Furthermore, evidence from clinical epidemiological studies suggests that medication use and alcohol dependence were not likely to have occurred separately. For example, in the NSDUH sample, among respondents who reported past-year dependence, 90 percent had drunk in the past 30 days.

The survey data do not allow us to determine which patients were receiving mental health counseling concurrent with medication treatment. However, results from community studies indicate that only a fraction of individuals in mental health treatment receive multiple sessions of counseling, and few receive counseling consistent with evidence-based guidelines ( 46 ). Furthermore, we do not know the exact psychiatric medication that patients received; we know only that the medication was taken for mental or emotional conditions. However, a large majority of psychiatric medications prescribed are SSRIs and other newer antidepressants and, to a lesser, degree benzodiazepines ( 47 ). Also, we cannot determine whether the placebo effect differed between those with and without alcohol dependence.

The possibility that psychiatric medications are effective in reducing psychiatric symptoms among individuals with alcohol dependence presents a puzzle with important implications for clinical management. Are physicians prescribing medications to substance-dependent patients because they are unaware of their substance use disorders ( 48 , 49 ) or because they believe that the medications are effective for patients with co-occurring disorders, despite the lack of a strong evidence base or professional consensus? In other words, are clinicians doing the right thing by doing the wrong thing or is this an example of clinical guidelines lagging behind clinicians in the field? This question can be resolved only through further research on physicians' prescribing decisions.

Despite these limitations, our study represents, to our knowledge, the first attempt to investigate patterns of medication use and patient-perceived effectiveness of psychiatric medications among alcohol-dependent patients. Our results are nationally representative and widely generalizable, because we examined the reported effectiveness of mental health treatment delivered in real-world settings in which no individuals were excluded because of physical or mental health or for other reasons. Furthermore, our sample is 15 times larger than the largest randomized control trial that Nunes and Levin identified ( 29 ).

Conclusions

The NSDUH data suggest that in mental health treatment settings, the presence of alcoholism does not inhibit prescription of psychiatric medication. Furthermore, patients perceive such treatment as effective, although perhaps slightly less so than patients without substance use disorders. These results support the finding of at least modest efficacy from available clinical studies. More research is needed that directly addresses medication efficacy for depression—and for a wider range of disorders, including anxiety disorders—among individuals with substance use disorders. More research is also needed on physicians' knowledge, beliefs, and prescribing behavior, as well on as their level of awareness of patients' substance use problems.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Office of Applied Studies of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and a Research Career Development Award (RCD-03-036) from the Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Services to Dr. Edlund.

1. Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, et al: The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 66:17-31, 1996Google Scholar

2. Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al: Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry 61:807-816, 2004Google Scholar

3. Vaillant GE: The National History of Alcoholism Revisited. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1993Google Scholar

4. Frances RJ: The wrath of grapes versus the self-medication hypothesis. Harvard Review of Psychiatry 4:287-289, 1997Google Scholar

5. Raimo EB, Schuckit MA: Alcohol dependence and mood disorders. Addictive Behaviors 23:933-946, 1998Google Scholar

6. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bergman M, et al: Comparison of induced and independent major depressive disorders in 2,945 alcoholics. American Journal of Psychiatry 154:948-957, 1997Google Scholar

7. Schuckit MA, Tipp JE, Bucholz KK, et al: The life-time rates of three major mood disorders and four major anxiety disorders in alcoholics and controls. Addiction 92:1289-1304, 1997Google Scholar

8. Chilcoat HD, Breslau N: Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:913-917, 1998Google Scholar

9. Strakowski SM, DelBello MP: The co-occurrence of bipolar and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review 20:191-206, 2000Google Scholar

10. Harris KM, Edlund MJ: Self-medication of mental health problems: new evidence from a national survey. Health Services Research 40(1):117-134, 2005Google Scholar

11. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, Md, Agency for Health Care Quality and Research. Available at www.guideline.gov. Accessed Nov 24, 2004Google Scholar

12. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research: Depression Guideline Panel: Depression in Primary Care: Vol. 2. Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1993Google Scholar

13. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for major depressive disorder in adults. American Journal of Psychiatry 150(Apr suppl):1-26, 1993Google Scholar

14. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with substance use disorders: alcohol, cocaine, opioids. American Journal of Psychiatry 152(Nov suppl):1-59, 1995Google Scholar

15. Clinical Guideline for Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), MDD With Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and MDD with Substance Abuse (SA). Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration, 1998Google Scholar

16. American Psychiatric Association Work Group on ASD and PTSD: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 161 (Nov suppl):3-31, 2004Google Scholar

17. Schulberg HC, Katon W, Simon GE, et al: Treating major depression in primary care practice: an update of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Practice Guidelines. Archives of General Psychiatry 55:1121-1127, 1998Google Scholar

18. Snow V, Lascher S, Mottur-Pilson C: Pharmacologic treatment of acute major depression and dysthymia. Annals of Internal Medicine 132:738-742, 2000Google Scholar

19. Whooley MA, Simon GE: Managing depression in medical outpatients. New England Journal of Medicine 343:1942-1950, 2000Google Scholar

20. VHA/DoD Performance Measures for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults, Version 1. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration, Feb 2000Google Scholar

21. VHA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults, Version 2. Washington, DC, Veterans Health Administration, Feb 2000Google Scholar

22. American Psychiatric Association work group on panic disorder. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry 155(May suppl):1-34, 1998Google Scholar

23. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). American Journal of Psychiatry 159 (Apr suppl):1-50, 2002Google Scholar

24. Watkins KE, Hunter SB, Burnam MA, et al: Review of treatment recommendations for persons with a co-occurring affective or anxiety and substance use disorder. Psychiatric Services 56:913-926, 2005Google Scholar

25. Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, et al: Consensus statement on generalized anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 62(suppl 11):53-58, 2001Google Scholar

26. Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, Lecrubier Y, et al: Consensus statement on social anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 59(suppl 17):54-60, 1998Google Scholar

27. Pettinati HM: Antidepressant treatment of co-occurring depression and alcohol dependence. Biological Psychiatry 56:785-792, 2004Google Scholar

28. Mason BJ, Kocsis JH, Ritvo EC, et al: A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of desipramine for primary alcohol dependence stratified on the presence or absence of major depression. JAMA 275:761-767, 1996Google Scholar

29. Nunes EV, Levin FR: Treatment of depression in patients with alcohol or other drug dependence. JAMA 291:1887-1896, 2004Google Scholar

30. Hernandez-Avila CA, Modesto-Lowe V, Feinn R, et al: Nefazodone treatment of comorbid alcohol dependence and major depression. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 28:433-440, 2004Google Scholar

31. Brady KT, Sonne SC, Roberts JM: Sertraline treatment of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 56:502-505, 1995Google Scholar

32. Randall CL, Thomas S, Thevos AK: Concurrent alcoholism and social anxiety disorder: a first step toward developing effective treatments. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 25:210-220, 2001Google Scholar

33. Randall CL, Johnson MR, Thevos AK, et al: Paroxetine for social anxiety and alcohol use in dual-diagnosed patients. Depression and Anxiety 14:255-262, 2001Google Scholar

34. Petrakis IL, Leslie D, Rosenheck R: The use of antidepressants in alcohol-dependent veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 64:865-870, 2003Google Scholar

35. Kranzler HR, Burleson JA, Brown J, et al: Fluoxetine treatment seems to reduce the beneficial effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy in type B alcoholics. Alcoholism Clinical and Experimental Research 20:1534-1541, 1996Google Scholar

36. Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, Luck G, et al: Double-blind clinical trial of sertraline treatment for alcohol dependence. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 21:143-153, 2001Google Scholar

37. Summary of Findings From the 2001 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Vol II. Technical Appendices and Selected Tables. Pub no (SMA)02-3759. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2002Google Scholar

38. Results From the 2002 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Pub no SMA(03-3836). Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2003Google Scholar

39. Results From the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Pub no SMA(04-3964). Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2004Google Scholar

40. Kessler RC, Barker PR, Colpe LJ, et al: Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry 60:184-189, 2003Google Scholar

41. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al: Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine 32:959-976, 2002Google Scholar

42. McAlpine DD, Mechanic D: Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: the roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Services Research 35:277-292, 2000Google Scholar

43. Mechanic D, McAlpine DD: Use of nursing homes in the care of persons with severe mental illness: 1985 to 1995. Psychiatric Services 51:354-358, 2000Google Scholar

44. Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, et al: The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 7:171-185, 1998Google Scholar

45. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:617-627, 2005Google Scholar

46. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al: The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:55-61, 2001Google Scholar

47. Stafford RS, MacDonald EA, Finkelstein SN: National pattern of medication treatment for depression, 1987 to 2001. Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 3:232-235, 2001Google Scholar

48. Cleary PD, Miller M, Bush BT, et al: Prevalence and recognition of alcohol abuse in a primary care population. American Journal of Medicine 85:466-471, 1988Google Scholar

49. Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Poses RM, et al: Physician detection of drinking problems in patients attending a general medicine practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine 7:517-521, 1992Google Scholar