Elimination of Methadone Benefits in the Oregon Health Plan and Its Effects on Patients

Oregon's innovative 1115 waiver, the Oregon Health Plan, (OHP) expanded Medicaid eligibility to all uninsured residents with an income equal to or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level (170 percent for women with children and pregnant women) and determined benefits through a unique ranking based on preventive value, cost-effectiveness, and public willingness to pay. On May 1, 1995, Medicaid recipients began receiving benefits for outpatient substance abuse treatment that included methadone maintenance. The expanded eligibility group included 20 percent of OHP members and accounted for 69 percent of beneficiaries who received alcohol and drug abuse treatment ( 1 , 2 ).

In October 2002 the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services created two levels of benefits: OHP Plus (full coverage for individuals who meet federal eligibility requirements) and OHP Standard (copayments and reduced benefits for individuals who meet the expanded eligibility requirements). The legislature was given authority to modify benefits in order to maintain budget neutrality. It eliminated outpatient mental health, substance abuse, and dental benefits effective March 1, 2003, and as a result, approximately 3,000 of 5,000 patients (60 percent) who were receiving methadone lost coverage for methadone maintenance. Patients were required to pay out of pocket or terminate care. Benefits were stopped after March 1, 2003, and patients who could not pay for further treatment went through detoxification from methadone beginning February 1, 2003, in anticipation of the benefit loss. Some patients went through detoxification at the time of their interview.

Prior investigations suggest that individuals who discontinue methadone maintenance frequently resume use of heroin, increasing medical, legal, family, employment, and psychiatric problems ( 3 , 4 ). Anglin and colleagues ( 3 ) conducted follow-up interviews with 331 individuals two-and-a-half years after closure of a publicly funded methadone treatment program. Individuals currently enrolled in methadone programs in three adjacent counties served as the comparison group (N=263). Patients who did not continue in care were more likely to report daily use of narcotics (men, 74 percent compared with 40 percent; women, 76 percent compared with 44 percent) and dealing drugs (men, 76 percent compared with 42 percent; women, 53 percent compared with 34 percent). Men who were no longer in care were also more likely to report committing property crimes, being incarcerated, and being under legal supervision. The group that continued in care had substantially better outcomes.

A random sample of 65 Miami patients was interviewed one month before and 12 months after closure of a methadone program. Comparison patients from a program in Jacksonville were interviewed at the same points in time (N=69). Estimated costs for health care use, costs of crime, and annual income did not differ between the two groups ( 5 ). However, patients reported receiving addiction treatment services in the 12 months after program closure, which may have attenuated potential negative impacts. The small sample and large variance in cost data suggest that the study may have been underpowered to detect differences.

Previous studies collected data post hoc or studied methadone clinic closures with clients in treatment at other agencies as their comparison groups. The study presented here differs from these previous investigations because our study was planned and executed as the benefits were being cut. This study investigated the short- and long-term effects among patients who were experiencing loss of methadone treatment benefits. The effects of this policy change were monitored as it occurred. Patterns of drug use, treatment-seeking behaviors, services received, and HIV risk behaviors were assessed for three groups formed as a result of the policy change: OHP Standard recipients who were detoxified and left methadone treatment (left-care group), OHP Standard recipients who were able to pay for and remain in methadone treatment (self-pay group), and OHP Plus recipients who did not lose benefits for methadone treatment (Plus group).

Methods

Sample

Approximately one month before the policy was changed (March 1, 2003), clients at a methadone program were approached and asked to be in the study. A sample of 151 methadone patients enrolled in the study in late February and early March 2003.

Initial interviews (February 2003; time 1) were completed with 149 individuals (two declined to participate in the study after providing consent). Medicaid classifications were based on evidence collected over the year. Follow-up interviews were completed approximately 30 days (April 2003; time 2), 90 days (June 2003; time 3), and one year (February 2004; time 4) after the policy change.

Procedures

When patients presented at the methadone window, the attendant handed them an invitation to visit the research office. Each patient consented to multiple interviews and gave researchers access to clinical records and state administrative databases. At baseline, trained interviewers completed the instrument battery that lasted approximately one hour. This process was repeated at times 2, 3 and 4. Participants were given a $20 dollar gift card at the completion of each assessment, and those who completed all four interviews received an additional $20 gift card. The Oregon Health and Science University's institutional review board reviewed and approved study procedures. A clinical record review of participant charts was conducted at the end of the second interview and at one-year follow-up.

Instrumentation

The Addiction Severity Index-Lite ( 6 ) assessed alcohol use, drug use, and legal issues, as well as employment, psychiatric, medical, and family and social issues. The composite scores were generated by algorithms unique to each score. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 1.00, with greater problems reflected in a higher score.

A 12-month Timeline Follow-Back assessment ( 7 ) covered the period from February 2003 to January 2004. The patients indicated by self-report when they used heroin, used needles that were previously used by someone else, injected drugs of any kind, received individual substance abuse treatment, received group substance abuse treatment, and received methadone. The variable has a range of possible scores of integers from 0 to 12 months.

Results

Sample

Data were analyzed for the 149 patients who participated. The sample consisted of 81 women (54 percent) and 21 patients who were married (14 percent). A total of 118 were Caucasian (79 percent), ten were African American (7 percent), 11 were Hispanic (7 percent), six were American Indian (4 percent), three were Asian (2 percent), and three did not disclose their race (2 percent). Patients and researchers knew the Medicaid status of the participants.

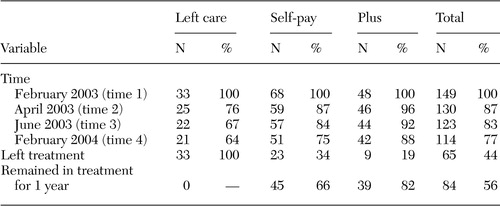

The final number of patients in each Medicaid group is presented in Table 1 . Follow-up interviews were completed for 130 patients (87 percent) at time 2, for 123 (83 percent) at time 3, and for 114 (77 percent) at time 4. Retention rates are reported in Table 1 and suggest that patients in the left-care group were the most difficult to retain in the study. Nonetheless, 64 percent of the individuals in the left-care group completed the one-year interview, although none maintained treatment for 12 months.

|

Retention in treatment

Medicaid status had a significant influence on retention in care (F=45.72, df=2, 146, p<.001). None of the 33 patients in the left-care group maintained treatment for 12 months. Twenty-one (64 percent) of the patients in this group were detoxified within ten weeks, five (15 percent) were detoxified over the course of the year at varying lengths, and seven (21 percent) left care abruptly. This finding is in contrast to the 68 patients who planned to self-pay: 45 (66 percent) were still in care 12 months after the policy change, 13 (19 percent) left treatment with a planned detoxification taper, and ten (15 percent) left treatment without detoxification. Of the 101 OHP Standard recipients who lost coverage, only 45 (45 percent) maintained methadone treatment for one year. None of the 48 OHP Plus recipients left methadone treatment in the first ten weeks after benefit reductions. Six patients (13 percent) planned detoxification over a longer period, three (6 percent) left treatment without notice, and 39 (81 percent) remained in treatment for the year.

Heroin use

Of the patients in the left-care group, 15 of 20 (75 percent) self-reported use of heroin during the year, compared with 19 of 51 (37 percent) in the self-pay group and 16 of 42 (38 percent) in the Plus group. Thirty-six patients had missing data on this variable because it was assessed at time 4. During the study period, patients in the left-care group reported using heroin for a significantly longer period compared with patients in the other two groups (left-care group, mean ±SD of 4.75±4.19 months; self-pay group, mean of 1.59±3.08 months; Plus group, mean of 1.00±1.89 month) (F=11.61, df=2, 110, p<.001).

Addiction Severity Index composite scores

Table 2 presents the ASI composite scores by Medicaid group. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) examined the significance of three effects: a Medicaid effect (a between-participants effect examining differences across Medicaid groups), a time effect (a within-participants effect examining increases or decreases over time), and a Medicaid group by time interaction (rates of change differing by group). Four univariate tests and the post hoc analyses were performed with a controlled type I error rate of .05 for each composite score. Participants with complete data at all four time points for each scale were included in the analysis (15 in the left-care group, 46 in the self-pay group, and 41 in the Plus group). Some data were missing on the psychiatric subscale for 11 participants.

|

The most pronounced differences were seen in the drug problems composite score. A multivariate effect was observed for time (Wilks' lambda=.900; F=3.59, df=3, 97, p=.016), indicating a decline in drug problems over the year: time 1, mean score of .057±.056; time 2, mean score of .049 ±.058; time 3, mean score of .049±.060; and time 4, .038±.054. A significant multivariate Medicaid group difference was observed (F=17.40, df=3, 99, p=.001). No significant time by Medicaid group interaction was found. Mean scores suggest that the left-care group had greater drug problems over the full year than the other two groups. Drug problems for this group were higher than those of the other two groups at time 1 because they were being detoxified from methadone. These scores increased at times 2 and 3 before decreasing at time 4. Even though some patients reported using alcohol to ease their withdrawal symptoms, the alcohol problems composite score was not affected significantly by time or Medicaid group.

The multivariate repeated-measures effect for the employment problems composite score showed no significant time or interaction effects. A significant multivariate Medicaid group difference was found (F=11.39, df=2, 99, p<.001), suggesting that for the four points in time there was a difference in the overall level of employment problems between the three groups. Patients who chose to pay out of pocket reported greater problems with employment than those in the left-care group or those covered by Plus. This finding suggests that employment was a major cause for concern among those attempting to pay the $300 per month for methadone treatment.

For the legal problems composite score, a significant multivariate difference was observed for time (Wilks' lambda=.860; F=5.40, df=3, 97, p=.002; time 1, mean score of .067±.138; time 2, mean score of .035±.088; time 3, mean score of .048±.119; and time 4, mean score of .043±.119) as well as a significant Medicaid group effect overall (F=9.94, df=2, 99, p=.001). There was a trend-level (p=.08) Medicaid by time interaction effect. At time 1, the left-care group reported more legal problems than the self-pay and Plus groups. The greater number of legal problems resulted from patients in the left-care group being more likely than those in the other two groups to be homeless and to have increased illegal activity. At times 2 and 3 the significant differences were between the left-care and the Plus groups. At time 4 no observable difference between the Medicaid groups was detected.

A significant multivariate repeated-measures effect for the family and social problems composite score was observed (Wilks' lambda=.789; F=8.64, df=3, 97, p=.001), indicating a decrease over time (time 1, mean score of .071±.099; time 2, mean score of .068±.098; time 3, mean score of .074±.105; and time 4, mean score of .021±.054). The greatest decrease was between times 3 and 4, indicating that during the period when methadone benefits were eliminated, patients reported strain in familial and social relationships. At one year, these issues appear to have resolved as the patient's social network adjusted to the changes.

No significant multivariate time effect or an interaction was found for the medical problems composite score, indicating that no systematic increase or decrease was observed. A significant multivariate Medicaid group difference was found (F=9.17, df=2, 99, p<.001). Scheffé's post hoc comparison tests suggest differences between the self-pay and the Plus groups. In the first four months after losing benefit coverage, patients who self-paid reported fewer medical problems than those in the Plus group. Patients in the Plus group had more medical problems than those in the other two groups, probably because many patients in the Plus group met qualifications for additional benefits because of disability.

A significant multivariate time effect was observed for the psychiatric problems composite score (Wilks' lambda=.856; F=6.26, df=3, 112, p=.001): time 1, mean score of .352±.228; time 2, mean score of .369±.227; time 3, mean score of .327±.223; and time 4, mean score of .336±.213. Psychiatric problems peaked at times 1 and 2 and then ameliorated somewhat at times 3 and 4. No time by Medicaid group effect was observed, but a significant Medicaid group effect was found (F=3.68, df=2, 114, p<.028). Significant differences were observed between the left-care group and the self-pay group. Patients in the self-pay group were more psychologically stable than those in the left-care group. Time 2 (one month after detoxification) showed the largest difference between the left-care group and the self-pay group. By time 4, the differences were not significant.

Risk behaviors and treatment seeking

Significantly more people in the left-care group (five of 20 patients, or 25 percent) reported injecting with previously used syringes than in the self-pay group (three of 51 patients, or 6 percent) or the Plus group (one of 42 patients, or 2 percent). Over the year, nine of 20 patients in the left-care group (45 percent) were homeless. This proportion was significantly higher than that found in the self-pay group (12 of 51 patients, or 24 percent) or the Plus group (one of 42 patients, or 2 percent) (F=9.52, df=2, 110, p<.001). Homelessness (and continued drug use) complicated patients' ability to find employment and stable housing.

Data from the Time Line Follow Back assessment indicated that patients in the left-care group attended fewer individual drug abuse counseling sessions than those in the other two groups. Patients in the left-care group attended individual substance abuse counseling on an average of 4.05±3.82 months over the year, whereas those in the self-pay group attended sessions for a mean of 7.39±5.03 months and those in the Plus group attended sessions for a mean of 8.86±4.59 months (F=7.15, df=2, 110, p=.001). The same results were found for group therapy (F=7.75, df=2, 110, p=.001); patients in the left-care group attended therapy for a mean of 4.00±3.85 months out of the year, whereas those in the self-pay and Plus groups attended sessions for 8.57±4.59 and 8.81±5.05 months out of the year, respectively.

Income and employment

The Addiction Severity Index documents income and number of days worked ( Table 3 ). A repeated-measures MANOVA with income as the dependent variable suggested a trend by time (Wilks' lambda=.926; F=2.55, df=3, 97, p=.060) and indicated an increase across all Medicaid groups. There was no time by Medicaid group interaction but a significant Medicaid group effect (F=7.71, df=2, 98, p<.001). Patients in the left-care group earned significantly less than those in the other two groups at times 1 and 2. At times 3 and 4, the left-care group earned significantly less than the self-pay group. The self-pay group had increasingly higher incomes at each time point.

|

Patients in the left-care group were more likely to be homeless and unemployed than those in the self-pay group. Patients in the Plus group were more likely to be retired or disabled. A MANOVA analyzing the number of days in the past 30 days that the patient worked showed no significant time effect or time by Medicaid interaction effect but a significant Medicaid group effect (F=30.67, df=2, 98, p<.001); the self-pay group worked significantly more days than the other two groups.

Discussion

This naturalistic study documenting the impact of a methadone benefit reduction for individuals who received Medicaid found that patients who left treatment used heroin and dirty needles and exhibited greater drug, legal, and psychiatric problems before the cuts and afterwards; employment problems were greater for patients in the self-pay group because working became a paramount concern; patients in the self-pay group earned more income and worked more days compared with the other groups; patients in the left-care group were more likely to be homeless over the study period than those in the self-pay group; and patients in the left-care group were less likely to be in treatment for substance abuse.

Some patients exhibited differences at the baseline assessment. The differences in medical problems were due to the fact that many of the Plus recipients were disabled. The greater legal problems were attributable to patients in the left-care group being more likely than those in the other two groups to be homeless and have legal problems. However, patients at baseline had been informed that they would be losing benefits before their interview. Thus employment problems were elevated for the self-pay group because of their need to work to pay for treatment. Drug problems were greater for the left-care group because of the anticipation of the loss of benefits that covered methadone maintenance.

Overall these benefit cuts disproportionately affected poor, homeless, and unemployed patients and patients with little social support. Patients who left treatment without attempting to self-pay had significant elevations in medical, legal, drug, and psychiatric problem scores. Patients who went through detoxification as a result of the benefit reduction used heroin to ease their withdrawal symptoms from a short detoxification taper and returned to using heroin upon leaving treatment.

Of the 101 patients who lost benefits, 45 percent were able to pay for their methadone and had more resources and better mental and physical health. Nineteen percent of patients who attempted to self-pay eventually went through the detoxification process from methadone, and 15 percent of those in the self-pay group abruptly stopped methadone treatment.

As with many longitudinal studies that follow a population with multiple stressors, attrition was a limitation in the final follow-up interviews. As a result the findings reported here probably underestimate the rate of heroin use in the left-care group. The population of methadone clients at the site was small, and random selection of participants was not possible.

Conclusions

These results present evidence that the administrative action taken by the Oregon state legislature to eliminate benefits for patients who received OHP Standard had a negative impact among those who could least afford loss of benefits. The impact on those who were unable to maintain their benefits may have shifted costs to increased property crimes, medical visits, and strain on public health agencies. Modification of eligibility criteria might have been a more effective cost-cutting measure for the legislature. Methadone benefits could have been eliminated only for patients who were able to pay for methadone maintenance, permitting individuals least able to self-pay to remain in care. Instead, this group was the most negatively affected.

In response to public concerns and the expense of inpatient care, benefits for outpatient mental health and addiction services were restored for OHP Standard recipients on August 1, 2004. The imposition of copayments and premiums continues to erode the number of people who participate in OHP Standard.

Acknowledgments

Development and implementation of this project was supported by grant 1-UDI-TI-12904-01 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment and the Oregon Practice Improvement Collaborative and grant R01-DA1-4688 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation continued the implementation with grant RWJ-048301, and the National Institute of Drug Abuse allowed for completion of the project with grant 1-R03-DA017710-01.

1. Deck DD, McFarland BH, Titus JM, et al: Access to substance abuse treatment services under the Oregon Health Plan. JAMA 284:2093-2099, 2000Google Scholar

2. Mitchell JB, Haber SG, Khatutsky G, et al: Children in the Oregon Health Plan: how have they fared? Medical Care Research and Review 59:166-183, 2002Google Scholar

3. Anglin MD, Speckart GR, Booth MW, et al: Consequences and costs of shutting off methadone. Addictive Behaviors 14:307-326, 1989Google Scholar

4. Hser Y, Hoffman V, Grella C, et al: A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Archives of General Psychiatry 58:503-508, 2001Google Scholar

5. Alexandre PK, Salomé HJ, French MT, et al: Consequences and costs of closing a publicly funded methadone maintenance clinic. Social Science Quarterly 83:519-536, 2002Google Scholar

6. McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al: The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 9:199-213, 1992Google Scholar

7. Sobell LC, Sobell MB: Timeline Follow-Up User's Guide. Toronto, Ontario, Addiction Research Foundation, 1996Google Scholar