Multiple-Family Group Treatment for English- and Vietnamese-Speaking Families Living With Schizophrenia

Comprehensive evidence has established family intervention as a powerful tool in the treatment of schizophrenia. After a correlation was found between family tension and relapse ( 1 ), a range of interventions has been developed to improve family atmosphere and reduce relapse.

Applying stringent methodological criteria, the Cochrane review of family interventions concluded that interventions incorporating an educational component to improve caregivers' understanding of mental illness, along with additional cognitive-behavioral interventions, are effective in reducing relapse at 12 and 24 months posttreatment ( 2 ). Family intervention studies have demonstrated reductions in relapse rates well below the expected two-year cumulative relapse rates of 64 percent obtained for standard care (case management and medication) ( 3 ). For instance, Leff and colleagues ( 4 ) in a small-scale study with 23 participants reported relapse rates of 36 percent for multiple- and single-family psychoeducation and support. In a study sample of 83 families, Tarrier and associates ( 5 ) found relapse rates of 33 percent for behavioral family therapy, including stress management and training in goal setting.

Although the primary focus of outcome studies has been relapse, there is also evidence that family interventions have a positive impact on other measures of client and family functioning, including negative symptoms ( 6 ), family burden ( 7 ), vocational outcomes ( 8 ), knowledge about schizophrenia ( 9 ), quality of life ( 10 ), and social adjustment ( 11 ).

The relative effectiveness of different types of treatment within family interventions has received little attention. Although all family interventions incorporate psychoeducation, standardized intervention models have focused on a variety of treatments, including behavioral family therapy, incorporating communication training to reduce family conflict and improve problem solving ( 12 ); social skills, problem solving, and the development of family support networks ( 13 ); and general supportive family therapy ( 14 ). Although these models have not been compared, replication studies and studies comparing these treatments with general family support provide some evidence about the consistency of treatment effects.

Studies of behavioral communication training have yielded mixed results. Earlier studies ( 5 ) indicated greater efficacy than a more recent trial, which did not show any benefit of intensive behavioral intervention over general family support on relapse or rehospitalization measures ( 15 ). Similarly, mixed results have been reported for supportive family therapy. One study reported no difference in outcomes between family therapy and caregiver support groups ( 14 ).

Consistent positive treatment effects have been associated with McFarlane's ( 16 ) multiple-family group intervention, an adaptation of Hogarty's ( 11 ) approach. Both are based on psychoeducation, problem solving, and development of social support networks. In a large-scale multisite study of 172 families that compared single- and multiple-family treatment, cumulative two-year relapse rates of 16 percent were reported for the multiple-family groups, compared with 27 percent for single-family therapy ( 17 ). Multiple-family treatment also showed superior outcomes in other measures of functioning, such as employment and perceived family burden. The positive effects of multiple-family group interventions that were seen in multisite trials have also been found in natural clinical settings ( 6 , 17 ). In these settings multiple-family groups were shown to be more cost-effective than standard care; savings from reductions in inpatient hospital admissions and from use of the group treatment format were estimated to yield a cost-benefit ratio of 1:17 for multiple-family group treatment compared with standard care ( 16 ).

Some variation is evident in the impact of the multiple-family group intervention on specific symptom profiles, which may be related to the types of patient groups in different studies. For instance, McFarlane and colleagues ( 16 ) used the multiple-family group intervention with people in an acute phase of illness and reported significant changes in acute symptoms. In contrast, a study by Dyck and associates ( 6 ), which involved 63 people with chronic schizophrenia in an outpatient setting, found that acute symptoms of consumers who received multiple-family group treatment were not affected but that their negative symptoms improved.

Several cross-cultural applications have identified family interventions as an efficacious treatment in international settings in which the cultural identification of the treatment group is consistent with the dominant culture ( 18 , 19 ). However, very little research has explored the impact of family intervention in migrant groups, even though it could be argued that these groups have the greatest need for family support. Common experiences of stress, isolation, and burden experienced by families dealing with mental illness are likely to be further intensified for newly settled migrant families because of language and communication difficulties, reduced access to extended family supports, and lack of knowledge of mental health services.

For example, Klimidis and associates ( 20 ) found lower rates of use of adult community mental health services among people of non-English-speaking backgrounds in Victoria, Australia, particularly among Asian and South East Asian communities. However, the only study that investigated the effectiveness of family interventions with a migrant population showed an adverse outcome. Telles and colleagues ( 21 ) assigned 40 Hispanic-American families of non-English-speaking backgrounds to behavioral family management or a case management control group. Behavioral family management made no significant clinical contribution beyond case management and medication, and compared with individual treatment, behavioral family management actually exacerbated symptoms of individuals who were defined as "less acculturated." The authors suggested that the psychoeducation and support packages developed for English-speaking cultures may contain directives that are culturally dystonic, such as expressing negative emotions in the presence of an authority figure within the family. Such findings have prompted some researchers to recommend caution in using family interventions for individuals from non-English-speaking backgrounds ( 22 ). However, very little attention has been directed to modifying family interventions to incorporate culturally sensitive practice, despite suggestions that cultural factors may have a profound influence on the way services are received and their effectiveness ( 23 ).

Our study compared outcomes for participants in a multiple-family group intervention for people with schizophrenia and their caregivers and a case management control group. The study sought to extend the multiple-family-group approach with appropriate cultural modifications to a newly arrived migrant group with a non-English-speaking background—first-generation Vietnamese families.

Methods

The study was conducted between September 1997 and July 2004 in the community mental health program of the Inner West Area Mental Health Service-Royal Melbourne Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. The service is one of 21 area mental health services funded by the state government and covers a geographical area that includes the central business district of Melbourne and a corridor of suburbs through the inner west area, with a population of 160,000 people.

The sample consisted of 59 consumers and their caregivers, of whom 34 pairs were English speaking and 25 were Vietnamese speaking. All consumers were recruited from outpatient continuing care settings. English-speaking consumers were recruited from the Inner West Area Mental Health Service. Although all the English-speaking consumers were born in Australia, two of the caregivers were born overseas. These two individuals had lived in Australia for more than 25 years and were proficient in English. Vietnamese-speaking consumers were recruited from the Inner West, Mid West, and South West Area Mental Health Services. All Vietnamese-speaking consumers and caregivers were born in Vietnam and had arrived in Australia as migrants or refugees between 1978 and 1985. A formal measure of acculturation was not used. However, acculturation and social adjustment has been shown to be strongly related to English fluency ( 24 ). Because 20 of the Vietnamese consumer-caregiver participants (80 percent) were not fluent in English and an interpreter was required for basic communication, the sample was considered to have a low level of acculturation.

Individuals eligible for inclusion in the study were those who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or schizophreniform disorder; who were aged between 18 and 55 years; and who had a minimum of ten hours of contact with family members each week. Consultant psychiatrists who had a minimum of 15 years of experience in public mental health settings used DSM-IV criteria to make clinical diagnoses. The presence of a comorbid diagnosis of substance use disorder was also determined. Institutional approval for the study was obtained from the Royal Melbourne Hospital research and ethics committee, and informed consent was obtained from all project participants.

The study followed standardized informed consent protocols to inform both consumer and family members about the purpose of the research, the practical requirements of the study, voluntary participation, and their rights in terms of confidentiality. Clients and caregivers were informed that because the research aimed to explore the effectiveness of standard case management compared with standard case management plus family treatment, some families would be offered family programs at random, and that consumer and family changes would be evaluated over 12 months of participation in both individual and family service programs. The plain-language statement and consent form was translated for Vietnamese-speaking consumers and caregivers. Consumers were initially invited by their case manager to take part in the service evaluation study, which consisted of two interviews over 14 months. They were asked to invite a caregiver to participate in the assessments. This procedure yielded a pool of participants from which the randomization process could occur.

After collection of pretreatment data, consumers and their caregivers within each cultural group were allocated randomly to a treatment or control condition by a staff member who drew names from a canister and, without looking at the names, assigned them to experimental and control groups. Treatment condition participants were then invited to take part in the multiple-family group intervention for 12 months.

Of the 73 consumers who met inclusion criteria and who were invited by their case managers, 59 consumers-caregiver pairs agreed to participate in the evaluation study. Caregivers included parents, siblings, and spouses. Of the 59 pairs, nine did not complete the data collection procedure after treatment or at 18 months (four in the control group and five in the treatment group). Four pairs assigned to the treatment condition declined to join the family group (three English speaking and one Vietnamese speaking). One participant in the multiple-family group died from a heroin overdose. A participant in the control group was lost through relocation, and two participants in the control group refused to complete the follow-up assessments. Follow-up data on relapse were not available for one participant in the control group who died from an overdose. Caregiver data were missing for two participants in the control group; one caregiver became ill, and a caregiver of a consumer who died declined to participate.

Clinical and social functioning assessments

Assessments were conducted using standardized measures with validated psychometric properties. They included the expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) ( 25 ), the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) ( 26 ), the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) ( 27 ), and the Quality of Life Scale (QOL) ( 28 ). Caregiver burden was measured with the Family Burden Scale ( 29 ). Independent researchers, who were blind to study condition, conducted the assessments. They were a clinical psychologist with experience in mental health and an experienced Vietnamese psychiatric-disability support worker who is also a qualified interpreter and translator. Both researchers underwent brief specific training in the use of the study measures at the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre. The BPRS standardized interview format was used, with the addition of the guidelines provided by Ventura ( 30 ). Video training was used to standardize the researchers' use of the QOL. A valid interrater reliability quotient was not achievable because of the incongruence between same-language and interpreted-language assessment.

Relapse

All participants were monitored over the course of the study for medication compliance and mental state. Case managers were asked to identify changes in symptoms using a monthly checklist that required them to rate on a 4-point scale any changes in frequency of contact, required social support, level of monitoring or interventions required, medication compliance, and changes in medications. The checklist also required case managers to indicate if they considered the consumer to be at risk of relapse or undergoing relapse. Examinations of patients' files were conducted after the study by researchers who were blind to the treatment condition to determine whether clinician-identified changes in symptoms constituted early-warning signs of relapse or full relapse. Early warning signs were defined as mood changes, a significant increase in persistent symptoms, increased contact with services, and use of rescue medication. Relapse was defined as the reemergence of frank psychotic symptoms after a period of remission of such symptoms, persisting continuously for a minimum of seven days and requiring intensive community treatment or hospital admission.

Time to relapse, time to hospitalization, number of episodes of relapse, and relapse duration were recorded. Data on early warning signs and relapse were collected at an 18-month follow-up by reviewing files and examining hospital admission data and by mailing questionnaires to current treatment providers for consumers who had been discharged from the service.

Control and treatment conditions

The case management intervention that was provided to all participants and that constituted the control condition consisted of regular appointments with a case manager and doctor to assess mental health and to provide medication and individual psychosocial rehabilitation on the basis of consumers' needs. Appointment frequency was every two to three weeks on average, and the sessions lasted from 30 minutes to one hour. Family contact was provided on an individual basis as required for all participants in the control and treatment groups. Family contact consisted of phone or direct contact and focused on providing psychoeducation, monitoring the consumer's mental state, and giving general support. Case management for Vietnamese participants in the control group was provided by a Vietnamese bilingual case manager when possible or with the use of Vietnamese interpreters.

Consumers assigned to multiple-family group treatment received the intervention as an adjunct to the standard case management intervention described above. Consumers' psychiatric registrars or psychiatrists did not participate in the group. On the basis of recommendations from meta-analyses of controlled outcome studies indicating that family treatment is effective when provided for a minimum of six months ( 31 ), families were regarded as having received the intervention if they attended 50 percent of the 26 sessions over the 12-month treatment period.

The multiple-family-group procedure was followed with minimal variation ( 32 ). Consumers and caregivers were provided up to three single-family joining sessions (described below) and then invited to attend two half-day multiple-family psychoeducation sessions. The family psychoeducation sessions provided information about schizophrenia using the approach described by Anderson and colleagues ( 33 ). The sessions gave family members the opportunity for informal social networking. Topics included the nature of the illness, treatment approaches (medication and psychosocial), consumer and family needs, common family reactions to illness, common problems that consumers and families face, and guidelines about what the family can do to help. The education was provided to the families by psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists. Each group of six or seven consumer-caregiver pairs was then invited to participate in a multiple-family group with two trained group leaders; groups met every other week for 12 months.

Although the multiple-family group intervention is generally used for two years, funding constraints necessitated a briefer intervention. Two Vietnamese-speaking and two English-speaking groups were conducted during the course of the study. Key components of each of the multiple-family group meetings were initial socializing, a "go-round" of current concerns for each family, a review of problems discussed in the previous meeting, and a combination of a discussion about a general topic and problem solving with a single family about a particular issue.

Staff training was initially provided by a three-day national workshop conducted by William McFarlane that outlined the multiple-family group method. The original multiple-family group format was varied only with respect to the inclusion of consumers in the family education sessions. Each of the English-speaking and Vietnamese-speaking groups had two therapists—a primary therapist and a support cofacilitator. The English-speaking and Vietnamese primary therapists were consistent for two intakes of the two cultural groups during the study to minimize variations in the application of the intervention. A cofacilitator was assigned to each of the four groups from a pool of two English-speaking and two Vietnamese-speaking therapists (a total of six therapists). Although treatment fidelity was not formally evaluated, the standardized treatment manual was used by group leaders. The manual was a critical tool in directing the structure and content of the sessions to maintain consistency of the therapeutic approach.

Regular supervision was provided to all group therapists by the lead primary therapist to the other five therapists. She was a senior psychologist and family therapist who was highly familiar with the McFarlane model. Additional external consultation was provided by a therapist at a specialist family therapy service, the Bouverie Centre. The theoretical orientation of the supervising therapists could be broadly described as systemic and congruent with McFarlane's approach.

Advice about cultural modifications to the multiple-family group intervention was provided by a Vietnamese therapist, who is part of a network of transcultural mental health specialists supported by the Victorian Transcultural Psychiatry Unit, a specialist teaching and research center. Cultural adaptations of the program included the use of Vietnamese-speaking staff for all aspects of service provision within the program. Family joining sessions were conducted informally on an outreach basis in the homes of the Vietnamese families to maximize the likelihood that families would engage with the service and to provide an opportunity to include as many family members as possible. Psychoeducation sessions acknowledged common ethnospecific explanatory models of illness before the biopsychosocial model of illness was outlined. Traditional alternative healing practices, such as herbal treatments and use of religious leaders, were acknowledged alongside Western approaches.

Statistical analyses

Because our objective was to determine whether the multiple-family group intervention would improve outcomes beyond those of case management alone for both Vietnamese-speaking and English-speaking groups, treatment effects were examined for the combined cultural groups. Although determining whether a specific treatment would be more effective for a particular cultural group was the secondary focus, such an analysis was beyond the scope of the study reported here because small samples provided insufficient statistical power. However, because the potential for negative outcomes of family treatment for migrant populations is of clinical and research importance, we examined and report trends in the data related to this issue.

Differences between the groups on the relapse measures were explored by using chi square analyses and survival analysis methods. To determine whether multiple-family group treatment improved functioning in other domains, dependent variables for which pre- and posttreatment scores were available were submitted to a series of analyses of variance—treatment (multiple-family group or case management) by time (pretreatment or posttreatment). The main hypotheses were tested by the presence of a group-by-treatment interaction on each measure using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (version 9.0).

Results

Sample characteristics and attendance

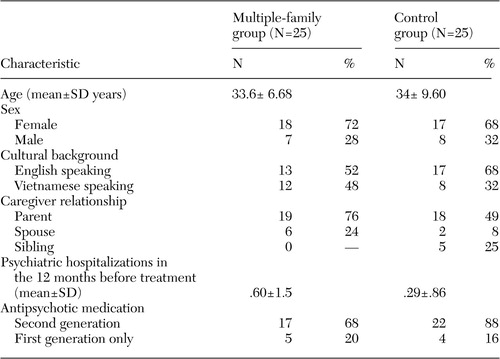

Demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1 . The mean age of participants in the control and treatment groups was about 34 years, and a majority of participants in the overall sample were female (70 percent) in each condition. The most common type of caregiver-consumer relationship was parent-adult offspring in both the multiple-family intervention (76 percent) and the control group (49 percent), although six caregivers in the Vietnamese multiple-family group were spouses (24 percent). Loss to follow-up was disproportionately higher among Vietnamese participants in the control group than among Vietnamese participants in the treatment group, either through relocation or refusal to participate in follow-up assessments.

|

The groups were compared for baseline differences by using chi square analyses and t tests for independent samples. Hospitalization history for the 24 months before study entry was examined to compare illness severity of the treatment and control groups. No significant differences between the groups were found. Of the total sample, 21 participants (42 percent) had received hospital treatment in the 24 months before baseline. Of the total sample, ten (20 percent) had an additional diagnosis of a substance use disorder. No difference was found between the groups on this variable. No differences were found between the treatment and control groups in medication compliance, and the mean self-reported monthly compliance rate was high (91 percent for the total sample).

Medication prescribing patterns were examined to determine whether there was any variation between groups in the use of first- and second-generation antipsychotics. No differences were evident in prescribing patterns between the groups. A significant pretreatment difference in participation in employment was found (N=50, χ 2 =8.0, df=47, p<.01); nine participants in the control group engaged in vocational training or part- or full-time employment, compared with one participant in the multiple-family group. No differences in English fluency were found between the Vietnamese-speaking treatment and control groups, suggesting a low level of acculturation for all Vietnamese participants.

Further tests on the dependent measures found no significant pretreatment differences between the treatment and control groups in scores on the BPRS, SANS, QOL, HoNOS, or Family Burden Scale. Pretreatment differences in the dependent measures between the two cultural groups were also examined. Scores were comparable for all of the variables with the exception of family burden. Family burden was rated as significantly higher among Vietnamese participants than among English-speaking participants (t=-8.2, df=47, p<.001).

All families participating in multiple-family group treatment attended the initial family psychoeducation day. As noted above, research indicates that family treatment is effective when provided for a minimum of six months. Attendance levels at the family group sessions (held every two weeks) were high; only two families in the treatment groups attended for less than six months. For the English-speaking groups, all but two families attended consistently for the 12 months of treatment. Two families attended inconsistently but continuously throughout the 12 months, attending approximately half the scheduled sessions (equivalent to six months of participation). In the Vietnamese-speaking multiple-family groups, all but two families attended for more than a total of six months. Seven families attended consistently for 12 months, one family for nine months, one family for six months, and two for less than six months (three and two months).

Relapse

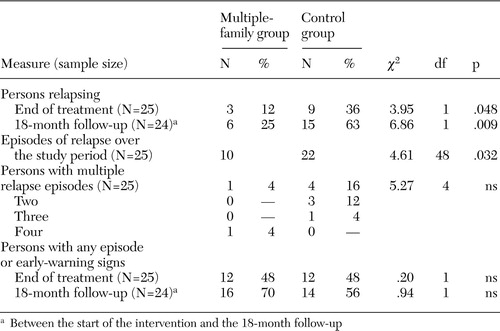

At the end of the 12-month intervention, relapse data were available for the whole sample. Data were incomplete at 18 months because of the death from a heroin overdose of one participant in the Vietnamese control group, the inability to locate another Vietnamese participant, and the death of a participant in the English-speaking treatment group. During the 30-month course of the study, 21 of the remaining 48 consumers (44 percent of the total sample) experienced a relapse. As shown in Table 2 , a significantly lower incidence of relapse was observed for participants who received the multiple-family group treatment; three participants (12 percent) experienced a relapse during the 12-month intervention period, compared with nine (36 percent) in the case management control group. At 18 months after the intervention, the difference in relapse rates was wider; six participants (25 percent) in the multiple-family group relapsed since the start of treatment, compared with 15 participants (63 percent) in the control group.

|

The duration of relapse was equivalent between the treatment and control groups. Multiple episodes of relapse were relatively infrequent, and no differences between the groups were evident.

Although the subsamples are too small for statistical analysis, it is interesting to examine relapse rates as a function of ethnicity as well as treatment condition. The overall trend identified for the combined cultural groups was consistent for Vietnamese participants. Vietnamese participants in the multiple-family intervention demonstrated low relapse rates immediately after treatment—8 percent (one participant), compared with relapse rates of 25 percent (two participants) for Vietnamese participants in the control group. At 18 months the relapse rate for Vietnamese participants in the multiple-family intervention was 27 percent (three of 11 participants), compared with 43 percent (three of seven participants) for the Vietnamese control group.

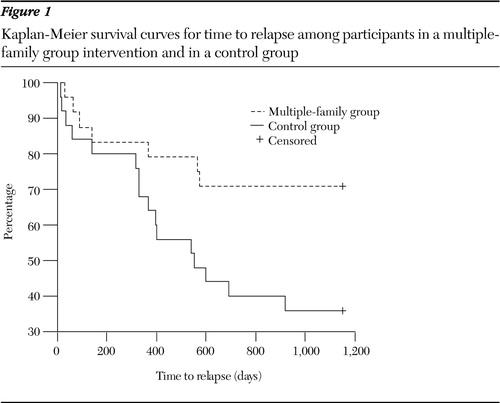

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for time to relapse for the treatment and control groups. A single covariate (treatment condition) estimates the effect. Mean time to relapse for participants in the treatment condition was 890 days, compared with 642 days for the control group. A significant difference between the curves was found for the two groups (log rank=5.22, df=1, p=.02). A Cox regression model fitted to the data led to the estimate that time to relapse in the treatment group was .37 times the time to relapse in the control group (χ 2 =5.28, df=1, 95 percent confidence interval=.151 to .899, p=.028).

Changes in symptom

We did not find any group differences in early-warning signs of relapse were identified for, as measured by reports of mood changes, a significant increase in persistent symptoms, contact with emergency services, or use of rescue medication

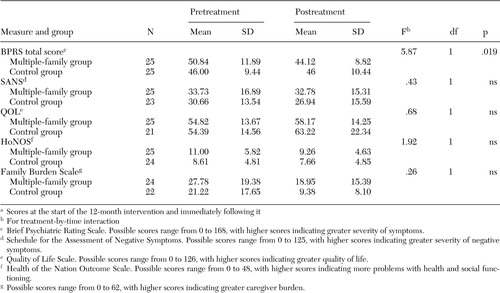

Table 3 presents mean scores for the groups on each measure. A significant interaction between treatment condition and time was found for BPRS scores. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (matched-pairs t tests) indicated a significant reduction between pre- and posttreatment BPRS scores for the multiple-family group (t=3.4, df=24, p<.01) but no difference for the control group. Further analysis of the four standard subscales of the BPRS ( 34 ) was conducted to explore the changes in greater detail. The analysis showed a significant interaction between treatment condition and time for the disorganization subscale (F=4.42, df=1, 46, p=.05) (conceptual disorganization, tension, and mannerisms); group differences showed a trend toward significance for thought disturbance (F=4.35, df=1, p=.05) (suspiciousness, hallucinatory behavior, grandiosity, and unusual thought content). Post hoc comparisons indicated that scores were significantly lower for participants in the multiple-family group on the thought disturbance subscale (t=2.4, df=24, p<.05) and showed a trend toward significance (p<.07) on the disorganization subscale, although no significant change was noted for the control group.

|

a Scores at the start of the 12-month intervention and immediately following it

No significant effects for SANS scores were found for the multiple-family group or the control group. Because of the small sample, data for the Vietnamese participants were not subjected to significance tests; however, trends for the Vietnamese sample were consistent with the findings for the combined groups. A mean±SD reduction in BPRS scores of 8.5±11.15 points was found for the Vietnamese-speaking multiple-family group, compared with a reduction of 1.8±10.37 points for the Vietnamese-speaking control group. This finding suggests that the culturally adapted multiple-family group was effective for Vietnamese participants in reducing psychiatric symptoms, whereas previous reports have found exacerbation of symptoms after family interventions.

Adjustment and role performance

The effect of the multiple-family group intervention on employment is difficult to determine because of significant pretreatment differences favoring the control group. At treatment entry, nine participants in the control group and one participant in the multiple-family group were engaged in employment-related activity (χ 2 =8.0, df =1, p=.005). Immediately after the intervention, differences between the groups were not found; seven participants in the control group and five in the multiple-family group engaged in employment. At 18 months postintervention, data were available for only 40 participants. The data indicated that differences between the groups had further diminished; five participants in each condition engaged in employment-related activity, suggesting that employment outcomes had worsened over time for the control group while they improved for the treatment group.

Outcomes for other measures of adjustment and functioning are presented in Table 3 . No group differences were found in scores on the HoNOS, Family Burden Scale, or QOL. A main effect of time on family burden was identified (F=28.61, df=1, 48, p<.001), indicating that both the multiple-family group and case management control were highly effective in reducing both objective and subjective measures of burden.

Discussion

The results of this study add to the growing evidence base for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral family interventions in the treatment of schizophrenia. Numerous researchers have noted that the benefits shown during the course of family treatment are not only maintained but strengthen over time, leading to extended periods without relapse and consistent relapse reduction rates of 25 percent at two-year follow-up ( 11 , 15 ). Consistent with these studies, our study found that multiple-family group treatment extended time to relapse and that treatment effects increased over time, with a greater contraction of relapse rates for the multiple-family group. Our relapse findings are also consistent with the literature on multiple-family groups; previous findings indicate two-year cumulative relapse rates of 25 percent ( 16 , 17 ). It is interesting that outcomes for relapse were similar in our study, in which only half the standard length of multiple-family group treatment was provided (12 months instead of 24 months).

Also in accordance with previous findings ( 16 ), BPRS symptom ratings in our study were significantly lower for the multiple-family group than for the control group immediately after the intervention. Subscale changes were significant for thought disorder and approached significance on positive symptoms such as paranoia, hallucinations, and conceptual disorganization. Unlike Dyck and colleagues ( 6 ), we did not identify any effect of multiple-family group treatment on negative symptoms, even though our sample was similar. Because the treatment protocol is standardized, it is not clear why different treatment outcomes were obtained for negative symptoms. The focus and content of the multiple-family groups may vary depending on the extent to which different types of symptoms are prioritized by families for discussion, problem solving, and psychoeducational input, which may lead to variations in the impact of treatment on different types of symptoms. It is also possible that the shorter treatment in this study reduced the impact of the intervention on negative symptoms.

The outcomes related to employment also suggest a positive impact of the multiple-family group intervention compared with the control intervention. Although the treatment group had significantly lower levels of employment than the control group at study entry, by the end of the follow-up period differences between the groups had disappeared, with equal numbers of participants engaged in employment-related activity. Despite pretreatment differences, it is clear that over two and a half years, employment outcomes had worsened for the control group and improved for the treatment group. The finding highlights the deleterious impact of relapse on functioning, as evidenced by losses of employment for control group participants, who experienced much higher relapse rates, and employment gains for participants in the multiple-family group, who demonstrated longer periods of remission between episodes. These findings are also consistent with numerous reports of positive employment outcomes associated with multiple-family group treatment ( 8 , 17 ) and support McFarlane and colleagues' ( 8 ) proposed interaction between symptom stability and vocational outcomes.

In contrast to other studies demonstrating that multiple-family group treatment is superior to other forms of treatment in reducing family burden ( 35 ), our study found that both the multiple-family group treatment and case management control treatment were highly effective in reducing family burden. Although the finding provides evidence for the effectiveness of the family-sensitive case management approach used in the mental health service, it is also possible that culture is a confounding variable. Highly significant pretreatment cultural differences were found, with Vietnamese families reporting extremely high rates of burden compared with the relatively low levels reported by English-speaking families. It is not possible to determine whether this finding was a specific factor related to Vietnamese ethnicity or an outcome of the migration experience. Intuitively it appears likely that relocated families who experience higher levels of vulnerability and isolation and the absence of an extended family to diffuse burden would be more responsive to any effective form of help. It is possible that both case management and the multiple-family group provide highly effective alternative support networks for problem sharing, problem solving, and emotional support and for reducing isolation.

It is also possible that the predominance of caregivers who were spouses among Vietnamese participants may have increased the levels of burden because of the additional impact of dependency factors specific to couples. Our finding of high levels of burden for Vietnamese families is also consistent with the results of other studies that identified high ratings of burden for Asian families in Hong Kong and China ( 36 ). Our finding further highlights the importance of providing adequate caregiver support, particularly for people from sociocentric cultures in which families assume a high level of responsibility for members with severe mental illness.

The results of this study provide an important contrast to previous evidence indicating an adverse outcome of family interventions in a migrant population ( 21 ). Although it was not possible to test statistically because of the small subsamples, the data trends suggest that the Vietnamese-speaking families and the English-speaking families responded similarly to the multiple-family group intervention in terms of relapse and BPRS symptom ratings. The findings related to symptom ratings are of particular interest. Unlike Telles and colleagues ( 21 ), who found that family intervention resulted in an exacerbation of symptoms among poorly acculturated Hispanic-American families, we found a reduction in BPRS ratings for both the Vietnamese- and English-speaking multiple-family group participants.

These findings must be interpreted cautiously because they were not subjected to significance tests and were from small subsamples. It should also be noted that the identified trend is specifically related to a Vietnamese migrant population and cannot be generalized to other migrant groups. There may be subtle interactions between characteristics of specific ethnic or migrant subcultures and treatment modality that have different effects on outcomes. Nevertheless, the trend does provide a basis for further use and evaluation of culturally modified family interventions for newly arrived non-English-speaking families and should provide a counterbalance for researchers and clinicians who may have been deterred from further exploration of the effects of family intervention with migrant populations by previous reports of symptom exacerbation.

Numerous writers have drawn attention to the difficulty of providing family support as a routine part of treatment in mental health services ( 37 ). The findings of this study prompt further reflection about the influence of cultural values in shaping service philosophy and configuration. In Asian cultures the family is a crucial social structure ( 38 ), and the burden of illness becomes a joint family obligation, with multiple members engaged in treatment. In contrast, Western cultural values emphasize individualism—for example, protection of the rights of the individual to privacy and confidentiality as well as independent living. Special attention to structural changes in the workplace may be necessary to counterbalance individualism in the mental health service culture to ensure the implementation of family-sensitive service systems.

The small sample was the principle limitation of the study, which prohibited more rigorous examination of the interaction of treatment and ethnicity. Although Vietnamese people represent one of the larger non-English-speaking communities in the inner west area of Melbourne, they tend to be represented in small numbers in the mental health service, and recruitment of Vietnamese participants proved problematic. Additionally, a large proportion of Vietnamese participants in the control group were lost to follow-up through relocation or refusal to participate. This outcome is itself of interest and suggests greater engagement of Vietnamese consumers and caregivers with services that are delivered with a focus on family participation. The effect of mixing spousal and parental caregivers within the Vietnamese multiple-family group is not known and may be another area for future research. Lack of assessment of treatment fidelity was also a limitation of the study design. Funding constraints also prevented collection of the full range of dependent measures at the 18-month follow-up, so that only relapse and employment data were explored.

Conclusions

It is possible to significantly improve clinical outcomes for consumers in a real-life clinical situation with relatively few additional resources by integrating family intervention into routine clinical practice. This study provided a strong basis for the continued use and evaluation of the multiple-family group approach with migrant families when specific cultural modifications are made. The data trends suggest that future exploration of family interventions with people from a range of cultural backgrounds and immigrant groups may be approached with cautious optimism. The observed variability in the impact of family treatment on symptom profiles warrants further investigation. Studies could explore the effects on specific treatment outcomes of variation in duration of treatment, group content, and relative emphasis on different problem or symptom areas.

Acknowledgments

The project was principally funded by grant 1997-0219 from the Victorian Health Promotion Foundation. The authors thank Henry Jackson, Ph.D., Margaret Leggatt, Ph.D., and Paul Maruff, Ph.D.

1. Berkowitz R, Eberlein-Fries R, Kuipers L, et al: Educating relatives about schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:418-429, 1984Google Scholar

2. Pharoah FM, Mari JJ, Streiner D: Family intervention for schizophrenia. Cochrane Library, Issue 2. Oxford, United Kingdom, Update Software, CD000088, 2003Google Scholar

3. Mueser KT, Bond GR: Psychosocial treatment approaches for schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 13:27-35, 2000Google Scholar

4. Leff J, Berkowitz R, Shavit N, et al: A trial of family therapy versus a relatives' group for schizophrenia: two-year follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry 157:571-577, 1990Google Scholar

5. Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Vaughy C, et al: Community management of schizophrenia: a two-year follow-up of a behavioural intervention with families. British Journal of Psychiatry 154:625-628, 1989Google Scholar

6. Dyck DG, Short RA, Hendryx MS, et al: Management of negative symptoms among patients with schizophrenia attending multiple-family groups. Psychiatric Services 51:513-519, 2000Google Scholar

7. Cuijpers P: The effects of family intervention on relatives' burden: a meta-analysis. Journal of Mental Health 8:275-285, 1999Google Scholar

8. McFarlane WR, Dushay RA, Deakins S, et al: Employment outcomes in family-aided assertive community treatment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 70:203-214, 2000Google Scholar

9. Pitschel-Walz G, Leucht S, Bauml J, et al: The effect of family interventions on relapse and rehospitalisation in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 27:73-92, 2001Google Scholar

10. Zastowny TR, Lehman AF, Cole RE, et al: Family management of schizophrenia: a comparison of behavioural and supportive family treatment. Psychiatric Quarterly 63:159-186, 1992Google Scholar

11. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM, Reiss DJ, et al: Family psychoeducation, social skills training, and maintenance chemotherapy in the aftercare treatment of schizophrenia: II. two-year effects of a controlled study on relapse and adjustment. Archives of General Psychiatry 48:340-347, 1991Google Scholar

12. Falloon IRH, Boyd JL, McGill CW, et al: Family management in the prevention of exacerbations of schizophrenia: a controlled study. New England Journal of Medicine 306:1437-1440, 1982Google Scholar

13. Hogarty GE, Anderson CM: Medication, family psychoeducation, and social skills training: first-year relapse results of a controlled study. Psychopharmacology Bulletin 22:860-862, 1986Google Scholar

14. Leff J, Berkowitz R, Shavit N, et al: A trial of family therapy v a relatives' group for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 154:58-66, 1989Google Scholar

15. Schooler NJ, Keith SJ, Severe JB: Relapse and rehospitalization during maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: the effects of dose reduction and family treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry 54:453-463, 1997Google Scholar

16. McFarlane WR, Link B, Dushay R, et al: The multiple family group and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia: four year relapse outcome in schizophrenia. Family Process 34:127-144, 1995Google Scholar

17. McFarlane WR, Lukens E, Link B, et al: Multiple-family groups and psychoeducation in the treatment of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry 52:679-687, 1995Google Scholar

18. Xiong W, Phillips MR, Hu X, et al: Family-based intervention for schizophrenic patients in China: a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:239-247, 1994Google Scholar

19. Xiang, MG, Ran MS, Li SG: A controlled evaluation of psychoeducational family intervention in a rural Chinese community. British Journal of Psychiatry 165:544-548, 1994Google Scholar

20. Klimidis S, McKenzie DP, Lewis J, et al: Continuity of contact with psychiatric services: immigrant and Australian-born patients. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 35:554-563, 2000Google Scholar

21. Telles C, Karno M, Mintz J, et al: Immigrant families coping with schizophrenia: behavioural family intervention versus case management with a low-income Spanish-speaking population. British Journal of Psychiatry 167:473-479, 1995Google Scholar

22. Drake RE, Goldman HE, Leff HS et al: Implementing evidence-based practices in routine mental health service settings. Psychiatric Services 52:179-182, 2001Google Scholar

23. Ziguras SJ, Stankovska M, Minas IH: Initiatives for improving mental health services to ethnic minorities in Australia. Psychiatric Services 50:1229-1231, 1999Google Scholar

24. Westermeyer J, Her C: English fluency and social adjustment among Hmong refugees in Minnesota. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 184:130-132, 1996Google Scholar

25. Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH et al: Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS), Expanded Version 4.0: scales, anchor points, and administration manual. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:227-243, 1993Google Scholar

26. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Iowa City, University of Iowa Press, 1983Google Scholar

27. Wing JK, Beevor AS, Curtis RH, et al: Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS): research and development. British Journal of Psychiatry 172:11-18, 1998Google Scholar

28. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon ET, Carpenter WT Jr. The Quality of Life Scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophrenia Bulletin 10:388-396, 1984Google Scholar

29. Pai S, Kapur RL: The burden on the family of a psychiatric patient: development of an interview schedule. British Journal of Psychiatry 138:332-335, 1981Google Scholar

30. Ventura J, Green MF, Shaner A, et al: Training and quality assurance with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale: "the drift busters." International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3:221-224, 1993Google Scholar

31. Mueser KT, Bond GR: Psychosocial treatment approaches for schizophrenia. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 13:27-35, 2000Google Scholar

32. McFarlane WR, Deakins SM, Gingerich SL, et al: Multiple-Family Psychoeducational Group Treatment Manual. New York, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1991Google Scholar

33. Anderson C, Hogarty G, Reiss D: Schizophrenia and the Family. New York, Guilford, 1986Google Scholar

34. Mueser KT, Curran PJ, McHugo GJ: Factor structure of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale in schizophrenia. Psychological Assessment 9:196-204, 1997Google Scholar

35. McFarlane WR, Dushay R, Stastny P, et al: A comparison of two levels of family-aided assertive community treatment. Psychiatric Services 47:744-750, 1996Google Scholar

36. Chan KE: The impact of schizophrenia on Hong Kong Chinese families. Hong Kong Journal of Social Work 29:21-34, 1995Google Scholar

37. Dixon L, McFarlane WR, Lefley H, et al: Evidence-based practices for services to families of people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services 52:903-910, 2001Google Scholar

38. Lin K, Cheung F: Mental health issues for Asian Americans. Psychiatric Services 50:774-780, 1999Google Scholar