Help Seeking for Substance Use Problems in Two American Indian Reservation Populations

The impact of alcohol use and misuse in American Indian populations has received extensive attention ( 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Furthermore, epidemiologic evidence shows rates of drug use among American Indian adolescents and young adults to be high ( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ). As a consequence, treatment of alcohol and drug problems is an important priority among persons entrusted with providing services to these populations ( 16 ).

Help seeking for alcohol problems among American Indians appears relatively high ( 8 , 17 , 18 , 19 ) and includes significant use of traditional healing resources ( 17 , 20 ). However, existing information about help seeking among American Indians has been constrained by a narrow focus on specific subgroups ( 17 , 20 , 21 ) and has not included a full complement of need variables, such as those suggested by other studies ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ). For example, although comorbid alcohol and mental health disorders are common, little is known about help seeking among persons with co-occurring conditions. Furthermore, although the overlap in help seeking from biomedical, traditional, and 12-step treatment modalities is thought to be extensive, we have little supporting empirical evidence. Finally, despite substantial ethnographic evidence on the importance of spirituality and ethnic identity ( 28 , 29 ), their roles have yet to be investigated, especially as they relate to the type of help sought.

The American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk, and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP), a population-based cross-sectional survey of two reservation populations, was designed to address such issues. This study assessed the extent of help seeking for alcohol and drug problems in the year before the interview, both overall and by modality (biomedical, traditional, and 12-step treatment modalities). We hypothesized that American Indians who use services would not only be more likely to have diagnoses of alcohol or drug use disorders but would also be more likely to have comorbid disorders and conditions. We further hypothesized that spirituality and ethnic identity would differentiate participants who sought help from traditional sources and 12-step programs from those who received help from biomedical sources only.

Methods

Sample and data collection

The AI-SUPERPFP methods have been explained in detail elsewhere ( 30 ). The population of inference was 15- to 54-year-old enrolled members of two closely related tribes (Northern Plains and Southwest) living on or within 20 miles of their respective American Indian reservations at the time of sampling in 1997. To protect the confidentiality of the two communities, we employed the general descriptors of Northern Plains and Southwest, rather than specific tribal names ( 31 ). Among the 4,126 tribal members located and found eligible for the study, 3,107 (75.3 percent) agreed to participate; of these, 2,825 (90.9 percent) had complete data for these analyses. Sample weights, used in all analyses presented here, accounted for differential selection probabilities across all strata and for nonresponse biases. Our Web site (www.uchsc.edu/ai/ncaianmhr/research/superpfp.htm) provides additional detail, including copies of the interview and the training manual.

As with similar investigations of help seeking ( 32 , 33 ), the current analyses were restricted to persons 18 years and older with complete data. The mean age was 34.9 years (95 percent confidence interval [CI]=34.8 to 35.0 years), and ranged from 18 to 57 years. A total of 1,598 (weighted estimate of 53.5 percent) were women (CI=53.1 to 54.0 percent).

Colorado multi-institutional review board approval was obtained before data collection as were the appropriate tribal approvals. All participants provided informed consent. Interviews were computer assisted and administered by tribal members intensively trained in research and interviewing methods.

Measures

Help seeking in the past year. Help seeking for substance use disorders was assessed in three sections of the interview. A health services section asked about service use in the past year by service sector (Indian Health Service, tribal, other biomedical, and traditional sources) separately for physical, alcohol or drug, and emotional problems. Within each diagnostic module, persons who endorsed some symptoms of the disorder were asked questions about help seeking from a mental health specialist, other medical personnel, and traditional healers. Finally, a separate set of questions focused on participation in 12-step programs.

The University of Michigan version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (UM-CIDI), used in the National Comorbidity Survey ( 32 ), formed the core assessment of service use tied to diagnostic symptoms. On the basis of focus group suggestions, the wording of questions was altered from asking about "seeing" service providers in the UM-CIDI to "talking to" such care providers in the AI-SUPERPFP. Furthermore, focus groups pointed out that speaking of use of traditional healing "services" made little sense. Rather one approaches a healer to ask for help, and the healer, "patient," and his or her family come together to seek resolution. The suggestion was made that this construct was best labeled "help seeking."

Analyses of these data showed that these service use questions represent overlapping and complementary perspectives on help seeking. The primary outcome measure—any help seeking for alcohol or drug use in the past year—combined reports from the service sector, diagnostic module, and 12-step participation sections. Help seeking is described here in terms of biomedical services, traditional healing, and 12-step programs, with the first two derived from the combined reports of the service sector and diagnostic modules.

Need variables. Others have shown the importance of broadening the definition of need beyond specific disorders of interest ( 34 ) to include comorbid disorders ( 32 , 35 ). Included here were alcohol and drug use disorders, tobacco use, depressive or anxiety disorders, and physical conditions. DSM-IV psychiatric disorders ( 36 ), both lifetime and in the past year, were assessed with the AI-SUPERPFP CIDI ( 37 ), yielding diagnoses for alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, drug abuse, and drug dependence (all included in alcohol and drug use disorders), major depressive episode, dysthymic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (all included in depressive or anxiety disorders). Questions were asked about any lifetime and past-year tobacco use. Physical conditions were assessed by using a self-report checklist of 31 chronic problems; included here were conditions that participants indicated had been diagnosed by a physician and were a problem in the preceding 12 months.

In attempting to understand the relationship between diagnoses and service use, we followed the lead of others ( 32 , 33 ) by creating summary variables that allowed investigation of both comorbidity and recency. Four mutually exclusive categories were created for depressive or anxiety disorders and physical health conditions: no problems, lifetime problems (but not in the past year), one problem in the past year, and two or more problems in the past year. In the case of substance use disorders, few persons qualified for a drug use disorder in the past year without an accompanying alcohol use disorder. Therefore, we created four categories: no substance use disorders, lifetime (but not past year) alcohol or drug use disorders, past-year alcohol use disorders, and past-year alcohol and drug use disorders.

Demographic characteristics. The analyses included the following demographic correlates: tribe (Southwest as referent), gender (women as referent), age (25 to 34 years, 35 to 44 years, and 45 years or older, compared with 18 to 24 years), formal educational attainment (high school or general equivalency diploma and some postsecondary education, compared with less than high school), employment status (student and unemployed, compared with working), and marital status (separated, widowed, or divorced and never married, compared with married or cohabiting).

Spirituality and ethnic identity variables. Three spiritual traditions were evident in these communities: culture-specific beliefs and practices, Christianity, and the Native American Church. Accordingly, these three indicator variables were used to mark the importance of these traditions in participants' lives. While these spiritual tradition variables paralleled assessments of religious affiliation in other studies ( 38 , 39 ), a general spirituality measure paralleled religiosity measures and assessed the overall importance of spirituality in everyday life (α=.80). This variable was dichotomized at the median. An ethnic identity scale ( 40 , 41 ) measured identification with both Indian (α=.73) and white cultures (α=.70); again, these were dichotomized so that one indicated strong identification with the culture.

Analyses

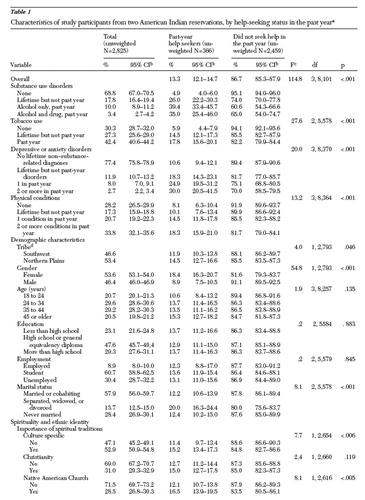

Variable construction was completed by using SPSS ( 42 ) and SAS ( 43 ); all inferential analyses were conducted by using Stata's "svy" procedures ( 44 ) with sample and nonresponse weights ( 45 ). Table 1 presents the distribution of the correlates within the population and also provides the distribution of help seekers by each correlate (row percentages). Table 2 presents logistic regressions comparing help seekers to non-help seekers for all participants with complete data (N=2,825). Table 3 is restricted to those who sought help in the past year (N=366); here multinomial logistic regressions simultaneously compared participants who used traditional services only, 12-step programs only, or multiple modalities, with those who used biomedical services only. Because of the weighted nature of the data, pseudo-F tests are presented throughout.

|

a Percentages are weighted.

|

a F=11.8, df=28, 2462, p<.001; the pseudo-F statistic tests whether the overall logistic regression equation meets the criterion of statistical significance.

|

a Users of biomedical services only were the comparison group (N=105). F=1.97, df=84, 238, p<.001; the pseudo-F statistic tests whether the overall logistic regression equation meets the criterion of statistical significance.

Results

In the full sample, 13.3 percent had sought help for problems with alcohol or drugs in the past year; among those with a lifetime substance use disorder, 30.3 percent (CI=27.2 to 33.5 percent) had sought help, and 37.7 percent (CI=32.8 to 42.9 percent) of those with past-year substance use disorders had done so (data not shown). As seen in Table 1 , 68.8 percent of respondents did not meet the criteria for having a substance use disorder in their lifetimes; 13.4 percent (CI=12.1 to 14.7 percent) had a past-year disorder, most related only to alcohol. Tobacco use was common. Less than one quarter of respondents qualified for lifetime depressive or anxiety disorders. A majority had at least one lifetime physical condition, and most reported at least one such condition in the past year.

Characteristics of past-year help seekers

The distributions of the correlates by help-seeking status indicated that help seeking for substance use problems among participants who did not meet criteria for substance use disorders was rare ( Table 1 ). However, 38.9 percent (CI=33.7 to 44.3 percent) of those with past-year alcohol or alcohol and drug use disorders had sought help (data not shown). Tobacco users, participants with depressive or anxiety disorders, and those with physical conditions were more likely than others to seek help for problems with alcohol and drugs. Such help seeking was more common in the Northern Plains, among men, and among those who were formerly married (separated, widowed, or divorced). Help seekers were more likely than those who did not seek help to place importance on their culture-specific traditions or the Native American Church. Regardless of spiritual tradition, help seekers were more likely to indicate that spirituality was important in their lives and to endorse a stronger Indian identity.

In Table 2 , the multivariate relationships of these variables to help seeking are described; this analysis controlled for other variables in the model. The past-year help seekers had increased odds of having a diagnosis of a substance use disorder; these odds increased for those with more recent alcohol and drug disorders. Use of tobacco, meeting criteria for having one or more depressive or anxiety disorders in the past year, and having two or more physical conditions in the past year were also related to help seeking for alcohol and drug problems. Males were more likely to be help seekers than females, and those who were formerly married were more likely to seek help than those who were married, cohabiting, or never married. Finally, help seekers were more likely to report greater general spirituality.

Treatment modalities

Among the past-year help seekers, more than half had used biomedical services, 42 percent had sought help from traditional sources, and 39 percent had used 12-step programs ( Figure 1 ). Within each modality, use of that type of service alone was most common; however, substantial overlap occurred. Use of traditional services was more common in the Southwest than in the Northern Plains (57.4 percent [CI=49.1 to 65.1 percent] compared with 31.7 percent [CI=25.3 to 38.9 percent], OR=.34, p<.001, Southwest tribe as reference category), whereas attendance at 12-step programs was more common in the Northern Plains than Southwest (47.0 percent [CI=40.2 to 54.0 percent] compared with 28.8 percent [CI=21.9 to 36.8 percent], OR=2.19, p<.001).

These findings led us to investigate the correlates of use of service modality. Focusing on the largest groups, we compared use of traditional sources only, use of 12-step programs only, and use of multiple modalities with the modal category of biomedical services only. As seen in Table 3 , compared with users of biomedical services only, those seeking help only from traditional sources were more likely to have lifetime but not current depressive or anxiety disorders, less likely to have two or more physical conditions in the past year, and less likely to have never been married. They were also more likely to ascribe to culture-specific spiritual traditions and to more strongly identify with Indian culture and customs. On the other hand, participants who used 12-step programs only were less likely than those who used biomedical programs only to meet criteria for having substance use disorders. Furthermore, even after the analyses controlled for other correlates, participants who used 12-step programs only were more likely to be from the Northern Plains, have more formal education, describe general spirituality as important in their lives, and express stronger identification with the white culture. Only higher levels of general spirituality differentiated those using multiple modalities from those seeking help from biomedical sources only.

Discussion

Valuable insights emerged from this study regarding the extent and distribution of help seeking in these populations of American Indians on reservations. It also yielded important preliminary findings about the correlates of help seeking in general with respect to the three specific treatment modalities.

Help seeking

In these reservation populations, 13.3 percent of study participants sought services for their substance use problems in the past year. The baseline National Comorbidity Survey (NCS), after which the AI-SUPERPFP measures were modeled, found a rate of 13.4 percent for past-year help seeking for mental and substance problems combined ( 46 ). Among those with past-year substance use disorders, 38.9 percent of AI-SUPERPFP participants sought help in the past year, whereas only 22.7 percent of the comparable NCS sample used some services in the past year ( 46 ). Although such comparisons must be treated cautiously, given our inclusion of both service-sector and diagnosis-centered measures of help seeking, previous analyses restricted to items common to AI-SUPERPFP and NCS ( 47 ) supported the conclusion that greater help seeking for alcohol or drugs problems occurs in these American Indian populations.

Our inquiry into the overlap, and lack thereof, of use of these modalities is unique among American Indians and proved to be essential to understanding the help-seeking process. Indeed, our estimates of help seeking would have been halved had we restricted these analyses to biomedical sources only.

Correlates of help seeking

Substance use disorders were related to help seeking in meaningful ways; participants who had more recent problems were most likely to seek help. Individuals who sought help for substance problems often had co-occurring mental and physical health problems, underscoring the opportunity for treatment settings to serve a triage function for such conditions—an especially important fact in the Indian Health Service and tribal health care systems, where physical and mental health services are seldom integrated ( 48 ). Given the high rates of tobacco use in these populations ( 49 ), a concurrent focus on smoking cessation in substance treatment settings would be valuable. In our sample, men were more likely than women to seek help for substance problems, a result also reported elsewhere ( 50 ). Help seekers were more likely to report spirituality as being important in their lives; however, given the cross-sectional nature of these data, whether such spirituality preceded or followed treatment (or both) was unknown.

Correlates of help seeking from different settings

Focusing first on participants who sought help only in traditional settings, we found that they had levels of diagnosable substance use disorders comparable to those who sought help in biomedical settings only. The finding that traditional settings appealed to those with past depressive or anxiety disorders may reflect the holistic nature of the traditional healing approaches ( 51 ).

Perhaps of greatest interest here was the inverse relationship between use of 12-step programs only and diagnosable levels of substance use. Subsequent analyses showed that participants who used 12-step approaches only were less likely to have met criteria for substance use disorders, either lifetime or past year, but they were also less likely to have had a drink in the past year and, when drinking, consumed less alcohol and were less likely to become drunk. Others have written about adaptations of Alcoholics Anonymous for American Indian populations, including a decreased emphasis on anonymity, formal procedures, and time orientation ( 52 ). Although it is unknown whether these adaptations were operational in the 12-step groups from which AI-SUPERPFP participants sought help, the AA groups participants attended may have served a preventive function by decreasing or maintaining lower consumption among individuals with subsyndromal levels of alcohol problems—especially for individuals in the Northern Plains, for individuals possessing more formal education, and for individuals more comfortable with white society. Comparing participants who used 12-step groups only with those who used biomedical services only, as we have here, represents an important new perspective on 12-step groups.

Spirituality and ethnic identity proved important in differentiating the treatment modalities used. Participants attracted to traditional sources for treatment indicated the importance of culture-specific spiritual traditions in their lives; they also identified with Indian culture. General spirituality strongly differentiated participants who used 12-step programs only or multiple modalities from those seeking help from biomedical sources only. Again, although any assertions of causality are unsupportable, all programs serving these populations should consider inclusion of optional, but diversified, spiritual components.

Limitations

Limitations in the AI-SUPERPFP sample, study design, and instrumentation have been discussed at length elsewhere ( 30 ). Several limitations were specific to the current analyses. Here, we combined reports across tribes. Although many of the publications about the AI-SUPERPFP ( 37 , 47 ) have underscored the importance of understanding tribal differences, our immediate questions were in regard to "who uses services and the characteristics of service users," rather than tribal comparisons per se. Combining the samples provided greater power for the modality analyses, for instance. Furthermore, the current effort did not assess the actual treatments received or their perceived efficacy and acceptability, although at least some literature suggests that substantial proportions of persons in need receive only short-term treatment with little positive impact ( 17 ). Furthermore, we did not include the full array of predisposing or enabling factors as suggested by the work of Andersen and Aday ( 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ). These are important next steps in our research agenda.

Conclusions

Although unmet need for alcohol and drug services certainly existed among American Indians who participated in our study, the percentage of participants in our study who were actively seeking services exceeded estimates for the general U.S. population—especially when traditional healing and 12-step programs were included in the calculus. Help seekers were likely to have co-occurring problems, suggesting the importance of triage within treatment settings. The relationships of spirituality and ethnic identity, in both the decision to seek services and the choice of modalities, deserve greater attention.

Acknowledgments

AI-SUPERPFP would not have been possible without the significant contributions of many people. The following interviewers, computer and data management staff, and administrative staff supplied energy and enthusiasm for an often difficult job: Anna E. Barón, Ph.D., Antonita Begay, Amelia T. Begay, Cathy A.E. Bell, Phyllis Brewer, Nelson Chee, Mary Cook, Helen J. Curley, Mary C. Davenport, Rhonda Wiegman Dick, Marvine D. Douville, Pearl Dull Knife, Geneva Emhoolah, Fay Flame, Roslyn Green, Billie K. Greene, Jack Herman, Tamara Holmes, Shelly Hubing, Cameron R. Joe, Louise F. Joe, Cheryl L. Martin, Jeff Miller, Robert H. Moran, Jr., Natalie K. Murphy, Melissa Nixon, Ralph L. Roanhorse, Margo Schwab, Ph.D., Jennifer Settlemire, Donna M. Shangreaux, Matilda J. Shorty, Selena S. S. Simmons, Wileen Smith, Tina Standing Soldier, Jennifer Truel, Lori Trullinger, Arnold Tsinajinnie, Jennifer M. Warren, Intriga Wounded Head, Theresa (Dawn) Wright, Jenny J. Yazzie, and Sheila A. Young. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of the Methods Advisory Group: Margarita Alegria, Ph.D., Evelyn J. Bromet, Ph.D., Dedra Buchwald, M.D., Peter Guarnaccia, Ph.D., Steven G. Heeringa, Ph.D., Ronald Kessler, Ph.D., R. Jay Turner, Ph.D., and William A. Vega, Ph.D. The authors thank the tribal members who so generously answered all the questions asked of them.

Furthermore, the AI-SUPERPFP team includes all the authors and Cecelia K. Big Crow, Dedra Buchwald, M.D., Buck Chambers, Michelle L. Christensen, Ph.D., Denise A. Dillard, Ph.D., Karen DuBray, Paula A. Espinoza, Ph.D., Candace M. Fleming, Ph.D., Ann Wilson Frederick, Joseph Gone, Ph.D., Diana Gurley, Ph.D., Lori L. Jervis, Ph.D., Shirlene M. Jim, Carol E. Kaufman, Ph.D., Ellen M. Keane, Suzell A. Klein, Denise Lee, Monica C. McNulty, Denise L. Middlebrook, Ph.D., Laurie A. Moore, Tilda D. Nez, Ilena M. Norton, M.D., Theresa O'Nell, Ph.D., Heather D. Orton, Carlette J. Randall, Angela Sam, James H. Shore, M.D., Sylvia G. Simpson, M.D., and Lorette L. Yazzie. This study was supported by grants R0-MH-48174 (Manson and Beals) and P01-MH-42473 (Manson) from the National Institutes of Health. Manuscript preparation was supported by grants R01-AA-13420 (Beals), R01-DA-14817 (Beals), R01-AA-13800 (Novins), and R21-AA-13053 (Spicer) from the National Institutes of Health.

1. Trends in Indian Health 1998-1999. Rockville, Md, Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

2. May PA, Gossage JP: New data on the epidemiology of adult drinking and substance use among American Indians of the northern states: male and female data on prevalence, patterns, and consequences. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research 10:1-26, 2001Google Scholar

3. May PA: Overview of alcohol abuse epidemiology for American Indian populations, in Changing Numbers, Changing Needs: American Indian Demography and Public Health. Edited by Sandefur GD, Rindfuss RR, Cohen B. Washington, DC, National Academy Press, 1996Google Scholar

4. Beauvais F: American Indians and alcohol. Alcohol Health and Research World 22:253-259, 1998Google Scholar

5. Mitchell CM, O'Nell TD, Beals J, et al: Dimensionality of alcohol use among American Indian adolescents: latent structure, construct validity, and implications for developmental research. Journal of Research on Adolescence 6:151-180, 1995Google Scholar

6. Beals J, Novins DK, Mitchell CM, et al: Comorbidity between alcohol abuse/dependence and psychiatric disorders: prevalence, treatment implications, and new directions for research among American Indian populations, in Alcohol Use Among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Multiple Perspectives on a Complex Problem. Edited by Mail P, Heurtin-Roberts S, Martin SE, et al. Bethesda, Md, US Department of Health and Human Services, 2002Google Scholar

7. Kunitz SJ, Gabriel KR, Levy JE, et al: Alcohol dependence and conduct disorder among Navajo Indians. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 60:159-167, 1999Google Scholar

8. Robin RW, Long JC, Rasmussen JK, et al: Relationship of binge drinking to alcohol dependence, other psychiatric disorders, and behavioral problems in an American Indian tribe. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 22:518-523, 1998Google Scholar

9. Federman EB, Costello EJ, Angold A, et al: Development of substance use and psychiatric comorbidity in an epidemiologic study of White and American Indian young adolescents the Great Smoky Mountains Study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 44:69-78, 1997Google Scholar

10. Beauvais F, Oetting ER: Variances in the etiology of drug use among ethnic groups of adolescents. Public Health Reports 117(suppl 1):S8-S14, 2002Google Scholar

11. Beauvais F: Trends in drug use among American Indian students and dropouts, 1975 to 1994. American Journal of Public Health 86:1594-1599, 1996Google Scholar

12. Novins DK, Beals J, Mitchell CM: Sequences of substance use among American Indian adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40:1168-1174, 2001Google Scholar

13. Plunkett M, Mitchell CM: Substance use rates among American Indian adolescents: regional comparisons with Monitoring the Future high school seniors. Journal of Drug Issues 30:593-620, 2000Google Scholar

14. Novins DK, Mitchell CM: Factors associated with marijuana use among American Indian adolescents. Addiction 93:1693-1702, 1998Google Scholar

15. Beals J, Piasecki J, Nelson S, et al: Psychiatric disorder among American Indian adolescents: prevalence in Northern Plains youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:1252-1259, 1997Google Scholar

16. Manson SM: Behavioral health services for American Indians: need, use, and barriers to effective care, in Promises to Keep: Public Health Policy for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 21st century. Edited by Dixon M, Roubideaux Y. Washington, DC, American Public Health Association, 2001Google Scholar

17. Robin RW, Chester B, Rasmussen JK, et al: Factors influencing utilization of mental health and substance abuse services by American Indian men and women. Psychiatric Services 48:826-832, 1997Google Scholar

18. Walker RD, Howard MO, Anderson B, et al: Substance dependent American Indian Veterans: a national evaluation. Public Health Reports 109:235-242, 1994Google Scholar

19. Walker RD, Howard MO, Lambert MD, et al: Psychiatric and medical comorbidities of veterans with substance use disorders. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 45:232-237, 1994Google Scholar

20. Gurley D, Novins DK, Jones MC, et al: Comparative use of biomedical services and traditional healing options by American Indian veterans. Psychiatric Services 52:68-74, 2001Google Scholar

21. Novins DK, Duclos CW, Martin C, et al: Utilization of alcohol, drug, and mental health treatment services among American Indian adolescent detainees. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1102-1108, 1999Google Scholar

22. Andersen R, Aday LA: Access to medical care in the US: realized and potential. Medical Care 16:533-546, 1978Google Scholar

23. Andersen RM: Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior 36:1-10, 1995Google Scholar

24. Aday LA, Andersen R: A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Services Research 9:208-220, 1974Google Scholar

25. Aday LA: Indicators and predictors of health service utilization, in Introduction to Health Services. Edited by Williams SJ, Torrens PR. Albany, NY, Delmar, 1993Google Scholar

26. Gochman DS: Handbook of Health Behavior Research: I. Personal and Social Determinants. New York, Plenum, 1997Google Scholar

27. Andrews G, Henderson AS: Unmet Need in Psychiatry. Cambridge, United Kingdom, Cambridge University Press, 2000Google Scholar

28. Brady M: Culture in treatment, culture as treatment: a critical appraisal of developments in addictions programs for indigenous North Americans and Australians. Social Science and Medicine 41:1487-1498, 1995Google Scholar

29. Weibel-Orlando J: Hooked on healing: anthropologists, alcohol, and intervention. Human Organization 48:148-155, 1989Google Scholar

30. Beals J, Manson SM, Mitchell CM, et al: Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry 27:259-289, 2003Google Scholar

31. Norton IM, Manson SM: Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 64:856-860, 1996Google Scholar

32. Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Leaf PJ: Influence of comorbid alcohol and psychiatric disorders on utilization of mental health services in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:1230-1236, 1999Google Scholar

33. Alegria M, Canino G, Rios R, et al: Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services 53:1547-1555, 2002Google Scholar

34. Alegria M, McGuire T, Vera M, et al: Changes in access to mental health care among the poor and nonpoor: results from the health care reform in Puerto Rico. American Journal of Public Health 91:1431-1434, 2001Google Scholar

35. Ross HE, Lin E, Cunningham J: Mental health service use: a comparison of treated and untreated individuals with substance use disorders in Ontario. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 44:570-577, 1999Google Scholar

36. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 1994Google Scholar

37. Beals J, Manson SM, Whitesell NR, et al: Prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and attendant help-seeking in two American Indian reservation populations. Archives of General Psychiatry 62:99-108, 2005Google Scholar

38. Koenig HG, Larson DB, Weaver AJ: Research on religion and serious mental illness. New Directions for Mental Health Services, no 80:81-95, 1998Google Scholar

39. Levin JS, Schiller PL: Is there a religious factor in health? Journal of Religion and Health 26:9-36, 1987Google Scholar

40. Moran J, Fleming CM, Somervell P, et al: Measuring bicultural ethnic identity among American Indian adolescents: a factor analytic study. Journal of Adolescent Research 14:405-426, 1999Google Scholar

41. Oetting ER, Beauvais F: Orthogonal cultural identification theory: the cultural identification of minority adolescents. International Journal of the Addictions 25:655-685, 1990Google Scholar

42. SPSS. Chicago, SPSS Inc, 2002Google Scholar

43. SAS Language. Cary, NC, SAS Institute, 2001Google Scholar

44. Stata Statistical Software. College Station, Tex, Stata Corp, 2003Google Scholar

45. Cochran WG: Sampling Techniques. New York, Wiley, 1977Google Scholar

46. Kessler RC, Zhao S, Katz SJ, et al: Past-year use of outpatient services for psychiatric problems in the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Psychiatry 156:115-123, 1999Google Scholar

47. Beals J, Novins DK, Whitesell NR, et al: Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: mental health disparities in a national context. American Journal of Psychiatry 162:1723-1732, 2005Google Scholar

48. Nelson SH, McCoy GF, Stetter M, et al: An overview of mental health services for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the 1990s. Hospital and Community Psychiatry 43:257-261, 1992Google Scholar

49. Nez Henderson P, Jacobsen C, Beals J, et al: Correlates of cigarette smoking among selected Southwest and Northern Plains tribal groups: the AI-SUPERPFP study. American Journal of Public Health 95:867-872, 2005Google Scholar

50. Wu LT, Kouzis AC, Schlenger WE: Substance use, dependence, and service utilization among the US uninsured nonelderly population. American Journal of Public Health 93:2079-2085, 2003Google Scholar

51. Napoli M: Holistic health care for native women: an integrated model. American Journal of Public Health 92:1573-1575, 2002Google Scholar

52. Jilek WG: Traditional healing in the prevention and treatment of alcohol and drug abuse. Transcultural Psychiatric Research Review 31:219-256, 1994Google Scholar