Racial and Gender Differences in Utilization of Medicaid Substance Abuse Services Among Adolescents

Substance use continues to be a public health problem ( 1 ) and is of specific concern for adolescents ( 2 , 3 ). In the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 10.6 percent of adolescents reported binge drinking, 21.8 percent had used illicit drugs and 34.3 percent had used alcohol within the last year, with 8.9 percent using substances at a level severe enough to be classified as abuse or dependence on alcohol or illicit drugs ( 4 ).

Because few persons who abuse drugs or alcohol receive treatment ( 4 , 5 ), concerns have been raised about disparities in utilization of substance abuse services for minorities and women. The focus of disparities research in health services has been on access to and utilization of physical health services ( 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ). Information on behavioral health services has been called for ( 6 , 10 , 11 ), with concerns raised about differences in access and utilization as well as differences in treatment and delay of treatment ( 7 , 8 ). Most of the studies on disparities in behavioral health care focus on mental health services, especially for adults ( 12 ), although child studies are increasing in number ( 13 ). There is a small but growing documentation of the presence of gender and race disparities in substance abuse services for adolescents. For instance, despite a "closing of the gap" in rates of substance use disorders between male and female adolescents ( 4 ), in clinical settings males were more likely to be identified with substance use problems ( 14 ) and receive some type of treatment ( 4 , 15 ).

Medicaid provides health care coverage for low-income individuals and families, the elderly, the blind and disabled, and people in need of long-term care ( 16 ). Medicaid has become the largest health insurance program in the country ( 17 ) and is the primary health insurer and most widespread public system in the United States for adolescents' health needs, covering more than one-quarter of all children and adolescents ( 18 ). Under federal guidelines, each state administers a program that provides required minimum benefits, but states may provide coverage to additional groups and additional services with federal matching dollars ( 19 ). Although states may limit Medicaid coverage for substance abuse services for adults, the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) program in Medicaid ( 16 , 19 ) nominally makes all needed services, including substance abuse services, available to youths ( 20 ).

However, little information is available on utilization of Medicaid substance abuse treatment across the states, and what studies are available do not address adolescent or race and gender issues separately ( 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ). One study specifically addressed utilization by adolescents receiving Medicaid coverage ( 25 ) and reported utilization rates for substance abuse treatment in four states, yet race and gender information was not included.

This study focused on one state's Medicaid program and utilization of adolescent substance abuse treatment. Tennessee's Medicaid program implemented a statewide managed care waiver demonstration program called TennCare in January 1994, authorized through Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, to cover all medical and behavioral services for youths and adults under a capitated fee structure paid to managed care organizations. Unlike other states where Medicaid does not cover certain types of substance abuse services (for example, in Oregon where residential or inpatient services are not covered) ( 26 ), the TennCare program offers all levels of substance abuse treatment and is intended to be the payer for all medically necessary services to enrollees. Covered services under TennCare for substance abuse include case management, outpatient therapy, intensive outpatient treatment, residential treatment, and inpatient services ( 27 ).

The objective of this study was to examine disparities in utilization of substance abuse treatment among minority and female adolescents enrolled in TennCare in Tennessee. As a means-tested program, TennCare, like the overall Medicaid program, covers children who are poor (family income of less than 100 percent of the federal poverty level) and "near poor" (family income of 100 to 199 percent of the federal poverty level) ( 16 ). Less than .1 percent of children enrolled in TennCare qualified under an eligibility category that allowed a family income above 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Therefore, in these analyses, the issue of race being confounded with socioeconomic status in previous research ( 7 , 28 ) is, in part, addressed.

Methods

Utilization of substance abuse services for the population of adolescents enrolled in TennCare was examined in two ways in this study. The first considered annual utilization rates and probability of substance abuse treatment. Utilization rates, defined as the proportion of a population who use a service (or type of service), have been recommended for examining service system performance in both the physical health and behavioral health literature, including substance abuse ( 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ). In recent work by the Washington Circle Group this type of service system performance measure has also been referred to as identification rate ( 29 , 33 ), but in this study the term "utilization rate" was chosen to indicate the overall rate of having at least one service contact ( 22 , 23 , 34 ).

The second utilization measure examined the age at which the first substance abuse service was received. This method has been used to explore race disparities in another study of the Medicaid population ( 35 ) and examines the issue of delays in problem identification. Concern has been voiced that persons from racial or ethnic minority groups may delay seeking care or that early symptoms may not be as readily identified ( 7 , 8 ). Delays in seeking substance abuse treatment, sometimes for years, have been documented ( 36 , 37 ), but race and gender differences have not been explored. Delays in obtaining health care, whether for medical or substance use issues, can result in increased severity of the disease. Severity of substance abuse may be an indicator of poor treatment outcomes and the need to repeat treatment later ( 38 , 39 ). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Vanderbilt University.

Sample

For the annual service utilization analyses, the sample was the statewide population of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years who were enrolled in Medicaid in this state during the study period. Each year, approximately 170,000 youths were in the program. For the "first use" analyses, the sample consisted of 8,473 adolescents who had their first substance abuse service paid for by TennCare during state fiscal years (SFY) 1997 to 2001.

Data

Data were extracted from the TennCare claims and encounter and enrollment data sets. The analytic years were SFY 1997 to 2001; SFY 1996 data permitted calculation of mental health service use during a previous year. A substance abuse service was any treatment for which a claim documented a primary or secondary diagnosis of a substance use disorder. Information about the completeness and accuracy of those data has been reported elsewhere ( 34 , 40 ), and others have reported results that were based on the TennCare data ( 41 ).

Measures

For the annual analysis, the utilization rate was defined as the proportion of adolescents aged 12 to 17 years who used at least one substance abuse service in a given year. The numerator was the unduplicated number of youths who received a substance abuse service paid for by TennCare, and the denominator was the unduplicated number of youths enrolled in TennCare for the same year. In the first-use analysis, age at first substance abuse service was calculated on the basis of the difference between the date of that service and the youth's date of birth, reported in years. Race and gender were the primary independent variables used to examine disparities. Other independent variables that have been shown or were hypothesized to be related to service use were included in the regression analyses as covariates to control for their influence on the dependent variables. These included Medicaid eligibility category, prior use of mental health services, and time (year of service).

Eligibility category was assigned on the basis of each enrolled youth's Medicaid eligibility category at the time of service, as identified on the claim form or from the enrollment file when the claims information was missing. Youths were assigned to one of six categories: Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for youths with a disability; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); Poverty Level Income Standard (PLIS), for youths who were poor but whose family income exceeded the poverty thresholds for TANF; Title IV-E, for youths in foster care; uninsured and uninsurable youths, expansion categories available under the TennCare waiver for youths who cannot get employer-sponsored insurance or who have preexisting conditions; and other eligibility ( 42 ). For the first-use analysis, a covariate for the number of months of Medicaid enrollment in the youth's lifetime before the first substance abuse service was added. For the annual utilization regression analysis, a dummy variable was coded for any mental health use in the previous year. However, for the first-use analysis, calculations included the number of visits for any type of mental health service in the 12 months directly preceding the substance abuse service.

Time was coded from 1 to 5 and represented each fiscal year. This category was included in the annual utilization analysis to control for the stages of implementation of managed behavioral health care. Time was excluded in the first-use analysis because time is contemporaneous with age.

Analysis

For the annual utilization analysis, a logistic regression was estimated for the annual probability of enrollees' use of a substance abuse service in the Medicaid program. In the first-use model, a linear regression was estimated on the basis of age (in years) at first substance abuse service use. SSI was chosen in the regression analyses as the referent for the eligibility categories because it has less state-to-state variability than TANF and other poverty-related Medicaid categories. Female was chosen as the referent for gender, and black was chosen for race.

Results

Utilization rate and probability of utilization

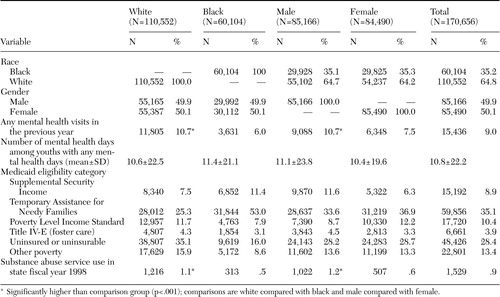

In Table 1 the characteristics of the statewide population of adolescents who were enrolled in TennCare are presented for SFY 1998, as an example of their characteristics during the study period. Overall, in these descriptive analyses less than 1 percent of the youths used a substance abuse service that year. White and male adolescents had overall utilization rates at least twice as high as those for black and female adolescents. When both race and gender were considered, white males had the greatest utilization rate (798 of 55,143 white males, or 1.45 percent), followed by black males and white females (255 of 30,521 black males, or .84 percent, and 452 of 55,409 white females, or .82 percent), with only 64 of 29,583 black females using a service (.22 percent).

|

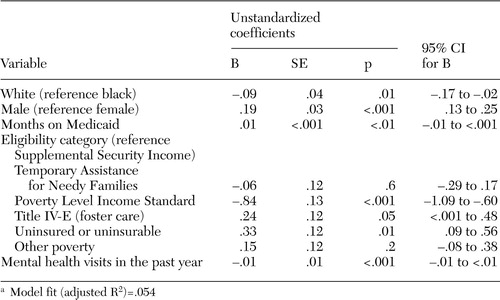

As shown in Table 2 , gender and race both remained significant predictors of utilization after the analysis controlled for other predictors in the model. Whites were nearly two times as likely as blacks to use substance abuse services, whereas males used services at a 78 percent greater rate than females. Several covariates were also statistically significant predictors of utilization. Youths in foster care had 3.7 times greater odds of using a substance abuse service, compared with those who received SSI, the eligibility category for youths with chronic disabling conditions. Youths in the uninsured or uninsurable and PLIS eligibility categories had the lowest rates of utilization of substance abuse services. Those with mental health services in the past year were 3.7 times as likely as those who had not had such a service to have had a substance abuse service. No significant trend was seen over time.

|

a Logit estimates: number of observations=1,033,757; Wald χ 2 =15,701.40, df=9, probability> χ 2 <.001; log likelihood=-51,363.241; pseudo R 2 =.0927; area under receiver operator characteristics (ROC) curve=.7726

Age at first substance abuse service

Table 3 displays the regression model for predicting age at first substance abuse service. Disparities by gender and race in age at first substance abuse treatment were statistically significant but not as compelling in magnitude. On average, females received a substance abuse service approximately two months earlier than males (15 years and four months compared with 15 years and six months), and whites received such a service one month earlier than blacks (15 years and five months compared with 15 years and six months). Several recent studies have supported the finding that women enter treatment at younger ages ( 43 , 44 ). Covariates that were also statistically significant predictors of age at first service use included eligibility category, months of Medicaid enrollment, and mental health visits in the prior year.

|

a Model fit (adjusted R 2 )=.054

Discussion

The multivariate analyses supported the findings of the descriptive analyses, demonstrating a significant relationship between being male and both utilization measures. Males had a greater probability of receiving a substance abuse service; males also received the first service at an older age than females, indicating that among those served, females were benefiting from earlier identification of their substance abuse problems. These gender disparities in access are not supported by available prevalence data in the general population—for example, the NSDUH data show that among adolescents in 2003, overall prevalence rates for substance abuse services were slightly higher for females than for males (9.1 percent compared with 8.7 percent) ( 4 ). Female adolescents also have been reported to have higher rates of co-occurring substance use and mental disorders ( 45 , 46 ) and to self-report more severe substance use and mental health symptoms ( 5 , 47 ), again in contrast to the findings of lower rates of service utilization.

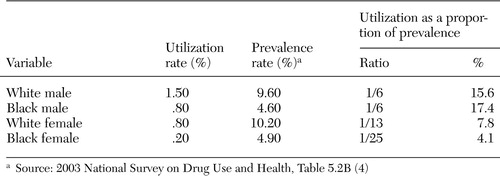

A statistically significant negative relationship was found between being a black adolescent and using substance abuse treatment. Not only were black youths less likely to get a service, but if they received treatment, it was at an older age. Overall, the disparities by gender and race in service utilization found in this study are greater than differences explained by prevalence rates. Harwood and colleagues ( 5 ) examined discrepancies in service use by comparing persons in need of treatment and those who received a service, and a version of this technique can be used with these findings. Prevalence rates in the 2003 NSDUH were used to examine which youths received treatment among those in need of treatment. The analysis found that white and black males were treated at essentially equivalent rates (one of six youths in need received a service), twice as frequently as white females (one of 13 youths), and almost four times as frequently as black females (one of 25 youths) ( Table 4 ). It should also be noted that an overall probability of service use of less than 1 percent is far below the "need" demonstrated for all the groups in the NSDUH data.

|

Although racial and gender disparities were the focus of this study, two other factors at the level of the service system should be recognized because of the strength of their association with utilization of substance abuse treatment. Medicaid enrollment category, specifically being in foster care, was a strong predictor in both analyses. The greater likelihood of youths in foster care to receive substance abuse treatment is probably related to both higher levels of need (for example, entering foster care because of problems) and a more knowledgeable adult (that is, the foster care worker), who could facilitate access to care. A similarly high odds ratio was found for previous mental health service use, likely also indicating a higher level of need (for example, the high prevalence of co-occurring disorders among adolescents) and, in this case, either a caregiver or service provider who already knew how to gain access to behavioral health services.

Study limitations

As noted above, this study included only adolescents in the Medicaid service system, which limits its generalizability. In addition, only Medicaid claims and encounter data were included. This study may underestimate the possible volume of youths who received substance abuse treatment, because some may have received services through other treatment sectors. However, in this state the comprehensive benefit package in the Medicaid program is intended to pay for all types of substance abuse services for adolescents. As in other states, the Substance Abuse, Prevention, and Treatment Block Grant, the other source of publicly funded substance abuse services for adolescents in Tennessee ( 27 ), is intended to be used for adolescents with no other public or private insurance. The focus of this study was on how Tennessee's Medicaid program, which is intended as the primary insurer for this population, identified substance use problems among its enrollees. An additional limitation is that the encounter data do not include a measure of the severity of the youth's substance use problem—for example, abuse compared with dependence.

Implications

How might these gender and racial disparities in service use, which are greater than what should be expected from differences in "need" for services, be better understood and addressed? Models explaining service utilization ( 48 ) and disparities in health care ( 49 ) acknowledge multiple factors at many levels. At the individual level, willingness to self-report behavioral health issues may differ by gender, race or ethnicity, or age ( 50 ). Also, evidence shows that treatment seeking is variable, with blacks more frequently using the religious community for support ( 51 ) and delaying initiation of formal health care services ( 7 ).

Professional and service system factors have been the focus of recent efforts and may be those most readily addressed. For instance, selective identification of substance use by providers during interactions for other reasons may be one factor that influences disparities. In a study of clinicians' accuracy in detecting the severity of substance abuse ( 14 ), although medical providers drastically underestimated substance use among all adolescents, they were better able to identify it among males than females. This discrepancy was related to the boys' high rates of past substance abuse that led clinicians to ask more in-depth questions. Similar identification and referral bias for mental health issues was found in favor of white over black children and adolescents ( 52 ), and apparent delay in identification and treatment of problems among black youths was also reported for children with autism who were enrolled in Medicaid ( 35 ).

To reduce disparities in identification of behavioral health issues, guidelines for primary care physicians and psychiatrists who treat adolescents that incorporate substance abuse screening ( 53 , 54 , 55 ) may be useful. Medicaid pays for annual preventive screens through the EPSDT program; yet use of these screens by adolescents is low ( 56 , 57 ). If adolescents' physician visits more often focus on an acute or chronic health concern, these opportunities need to be used for including preventive screens as well. However, the pressures to curtail the amount of time spent in office visits is a countervailing force, highlighting the interaction between the provider and system levels that influences service delivery.

Other system-level issues that may lead to disparities in behavioral health care utilization include differences in health insurance (although not in this study because all youths had the same TennCare coverage) and in the available network of providers that are convenient to minority communities, as well as broader economic and political issues ( 7 , 8 , 48 ). One concern that has been raised by research in other service sectors is that black youths may be more likely to end up in the juvenile justice system than the specialty treatment system when they get in trouble in community settings ( 58 ). Blacks have been shown to be more likely to enter the behavioral health treatment system through the legal system ( 59 ).

Specifically citing fragmentation and gaps in the current service delivery system, the President's New Freedom Commission ( 60 ) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration ( 61 ) have recently highlighted the need to "transform" service delivery not only for individual youths but also at the system level. Given the relationship found in this study between utilizing substance abuse services, being in foster care, and having received a previous mental health service, it is critical that the child-serving systems coordinate assessment, treatment planning, service delivery, and provider training regarding youths involved in multiple service systems in order to identify and treat behavioral and physical health problems, as well as other issues.

To monitor progress at the system level, policy makers need good information that may be enhanced by performance measures ( 29 , 31 , 62 ) and relevant behavioral health services research. The use of existing data sets, such as Medicaid, provides much-needed information. These findings indicate the importance of appropriate monitoring of and research about service utilization, not only broadly but for key population groups, such as adolescents and minority groups ( 7 , 63 , 64 ). Others have also recommended that subpopulations of beneficiaries be distinguished in plan report cards, such as Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures ( 31 ), to monitor the effect on these special needs groups. English and colleagues ( 65 ) emphasized the issues involved in meeting the needs of adolescents under managed care and the need for monitoring their care as a special population.

However, as an example of the intersection between provider and service system factors that reduce the ability to monitor service delivery, it is likely that adolescents' substance abuse is being identified and treated without a formal diagnosis on the claim. Sixty percent of 940 pediatricians recently surveyed ( 66 ) reported having diagnosed or treated adolescents for tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana use. However, there are disincentives, not only for physicians but also for behavioral health providers, to document substance abuse diagnoses. Concern regarding stigma and respect for the youth's privacy when the likelihood of treatment is small is a significant barrier to identification. Under managed care with behavioral health carve-outs, like TennCare, physicians on the "medical" side have reported denial of payment for services with "behavioral" diagnoses ( 57 ), despite EPSDT regulations ( 67 ). Similarly, behavioral health providers are encouraged to document serious emotional disorders among children and adolescents, and there are payment incentives for doing so; however, documentation of a co-occurring substance abuse disorder may raise more reimbursement issues ( 27 ). If good information is needed to guide improvement in service delivery, it will be important to overcome barriers to accurate and full documentation of substance abuse diagnoses in encounter and claims data.

Conclusions

This study is a first step in the exploration of health care disparities for adolescents with substance use problems. Further research is needed to examine the factors that influence utilization of substance abuse treatment and the racial and gender disparities found. Longitudinal, epidemiologic studies could help provide valuable information on the development, identification, and treatment of substance use, abuse, and dependence. Implementation studies could inform efforts to improve service provision and help move evidence-based practice into community-based clinical settings. As the recent Institute of Medicine ( 7 ) report highlighted, there are patient-level, provider-level, and system-level factors involved in disparities that need further exploration to address this issue, and all of these levels of factors should be included in future research.

Acknowledgments

Collection of the data used in this study was funded by grant UR7-TI11332 from the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (CSAT) and grant UR7-TI11304 from the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Preparation of this article was supported by grant 1-KD1-TI12328 from CSAT and grant RO1-DA12982 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors thank Nagambal Shah, Ph.D., for her guidance in this project and Kelly Taylor-Richardson, M.S.W., M.A., for her consultation.

1. Substance Abuse: The Nation's Number One Health Problem: Key Indicators for Policy—Update. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2001Google Scholar

2. Physician Leadership on National Drug Policy: Adolescent Substance Abuse: A Public Health Priority. Providence, RI, Brown University, Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, 2002Google Scholar

3. Dennis ML: Treatment research on adolescents' drug and alcohol abuse: despite progress, many challenges remain (invited commentary). Connection. Washington, DC, Academy for Health Services Research and Health Policy, 2002Google Scholar

4. Results of the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 2004Google Scholar

5. Harwood H, Sullivan K, Malhotra D: Data analysis identifies major disparities in alcohol treatment access across various groups. Frontlines: Linking Alcohol Services Research and Practice 4:7, 2001Google Scholar

6. National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Dec 2003Google Scholar

7. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, National Academies Press, 2003Google Scholar

8. LaVeist TA (ed): Race, Ethnicity, and Health. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 2001Google Scholar

9. Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health, 2nd ed. Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Nov 2000Google Scholar

10. Hines-Martin V, Malone M, Kim S, et al: Barriers to mental health care access in an African-American population. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 24:237-256, 2003Google Scholar

11. Surgeon General: Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC, United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2001Google Scholar

12. Chow JC, Jaffee K, Snowden L: Racial/ethnic disparities in the use of mental health services in poverty areas. American Journal of Public Health 93:792-797, 2003Google Scholar

13. Wu P, Hoven CW, Bird HR, et al: Depressive and disruptive disorders and mental health service utilization in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 38:1081-1090, 1999Google Scholar

14. Wilson C, Sherritt L, Gates E, et al: Are clinical impressions of adolescent substance use accurate? Pediatrics 114:536-540, 2004Google Scholar

15. Wu P, Hoven CW, Fuller CJ: Factors associated with adolescents receiving drug treatment: findings from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:190-201, 2003Google Scholar

16. Schneider A, Fennel K, Long P: Medicaid Eligibility for Families and Children. Washington, DC, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 1998Google Scholar

17. Weil A: There is something about Medicaid. Health Affairs 22(1):13-30, 2003Google Scholar

18. Health Care Coverage for Low-income Children. Washington, DC, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, 2004Google Scholar

19. Overview of the Medicaid Program. Washington, DC, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2003Google Scholar

20. TennCare Standard Operating Procedures (TSOP-36 and Addendum: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment [EPSDT]). Nashville, Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration, Bureau of TennCare, Apr 1999Google Scholar

21. Deck DD, McFarland BH: Use of substance abuse treatment services before and after Medicaid managed care. Psychiatric Service 53:802, 2003Google Scholar

22. Deck DD, McFarland BH, Titus JM, et al: Access to substance abuse treatment services under the Oregon Health Plan. JAMA 284:2093-2099, 2000Google Scholar

23. Ettner SL, Denmead D, Dilonardo J, et al: The impact of managed care on the substance abuse treatment patterns and outcomes of Medicaid beneficiaries: Maryland's Healthy Choice Program. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:41-62, 2003Google Scholar

24. McCarty D, Argeriou M: The Iowa managed care substance abuse care plan: access, utilization, and expenditures for Medicaid recipients. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 30:18-25, 2003Google Scholar

25. Heflinger CA, Saunders RC, Mulkern V, et al: Access to Medicaid-Financed Substance Abuse Treatment Services for Adolescents. Nashville, Vanderbilt University, 2003Google Scholar

26. Gabriel R, Grover J, Laws K, et al: Delivering Substance Abuse Treatment to Oregon's Adolescents: The Structure and Implementation of a Complex Interagency System. Portland, Ore, RMC Research Corp, 2001Google Scholar

27. Northrup D, Heflinger CA: Substance Abuse Treatment Services for Publicly-Funded Adolescents in the State of Tennessee. Nashville, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies, Center for Mental Health Policy, 2000Google Scholar

28. Navarro V: Race or class or race and class: growing mortality differentials in the United States. International Journal of Health Services 21:229-235, 1990Google Scholar

29. Garnick DW, Lee MT, Chalk M, et al: Establishing the feasibility of performance measures for alcohol and other drugs. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:375-385, 2002Google Scholar

30. McCorry R, Garnick D, Bartlett J, et al: Developing performance measures for alcohol and other drug services in managed care plans. Joint Commission on Quality Improvement 26:633-643, 2000Google Scholar

31. Health Plan Employer Data and Information Set (HEDIS). Washington, DC, National Committee for Quality Assurance, 2002Google Scholar

32. National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, Md, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Dec 2003Google Scholar

33. Lee MT, Garnick DW, Miller K, et al: Adolescents with substance abuse: are health plans missing them? Psychiatric Services 55:116, 2004Google Scholar

34. Saunders RC, Heflinger CA: Access to and patterns of use of behavioral health services among children and adolescents in TennCare. Psychiatric Services 54:1364-1371, 2003Google Scholar

35. Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, et al: Race differences in the age at diagnosis among Medicaid-eligible children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 41:1447-1453, 2002Google Scholar

36. Kessler RC, Olfson M, Berglund PA: Patterns and predictors of treatment contact after first onset of psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:62-69, 1998Google Scholar

37. Olfson M, Kessler RC, Berglund PA, et al: Psychiatric disorder onset and first treatment contact in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry 155:1415-1422, 1998Google Scholar

38. Anglin MD, Hser YI, Grella CE: Drug addiction and treatment careers among clients in the drug abuse treatment outcome study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 11:308-323, 1997Google Scholar

39. Hser Y, Joshi V, Anglin MD, et al: Predicting posttreatment cocaine abstinence for first-time admissions and treatment repeaters. American Journal of Public Health 89:666-671, 1999Google Scholar

40. Division of State Audit: Performance Audit: Medicaid Encounter Data: December 2001. Nashville, Comptroller of the Treasury, 2002Google Scholar

41. Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Fuchs C, et al: New users of antipsychotic medications among children enrolled in TennCare. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 158:753-759, 2004Google Scholar

42. TennCare Eligibility. Nashville, Tennessee Department of Finance and Administration, Bureau of TennCare, 2002Google Scholar

43. Green CA, Polen MR, Dickinson DM, et al: Gender differences in predictors of initiation, retention, and completion in an HMO-based substance abuse treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23:285-295, 2002Google Scholar

44. Pettinati HM, Rukstalis MR, Luck GJ, et al: Gender and psychiatric comorbidity: impact on clinical presentation of alcohol dependence. American Journal on Addictions 9:242-252, 2000Google Scholar

45. Dakof G: Understanding gender differences in adolescent drug abuse: issues of comorbidity and family functioning. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 32:25-32, 2000Google Scholar

46. The Relationship Between Mental Health and Substance Use Among Adolescents. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies, 1999Google Scholar

47. Stevens SJ, Estrada B, Murphy BS, et al: Gender differences in substance use, mental health, and criminal justice involvement of adolescents at treatment entry and at three, six, twelve, and thirty month follow-up. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 36:13-25, 2004Google Scholar

48. Andersen RM, Yu H, Wyn R, et al: Access to medical care for low-income persons: how do communities make a difference? Medical Care Research and Review 59:384-411, 2002Google Scholar

49. Williams DR, Jackson PB: Social sources of racial disparities in health. Health Affairs 24(2):325-334, 2005Google Scholar

50. Shillington AM, Clapp JD: Self-report stability of adolescent substance use: are there differences for gender, ethnicity, age? Drug and Alcohol Dependence 60:19-27, 2000Google Scholar

51. Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Douglas F: Parental religiosity, family processes, and youth competence in rural, two-parent African American families. Developmental Psychology 32:696-706, 1996Google Scholar

52. Cuffe SP, Waller JL, Cuccaro ML, et al: Race and gender differences in the treatment of psychiatric disorders in young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 34:1536-1543, 1995Google Scholar

53. Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders: AACAP. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36:4S-20S, 1995Google Scholar

54. Werner MJ, Hoover A Jr: Early identification and intervention for adolescent alcohol use. Adolescent Health Update (American Academy of Pediatrics) 10(1):1-8, 1997Google Scholar

55. American Academy of Pediatrics: Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in the management of substance use. Pediatrics 101:125-128, 1998Google Scholar

56. English A: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment Program (EPSDT): a model for improving adolescents' access to health care. Journal of Adolescent Health 14:524-526, 1993Google Scholar

57. Heflinger CA, Gaensbauer R: Tennessee's Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment (EPSDT) Program: A Survey of Primary Care Providers About Implementation Issues. Nashville, Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies, Center for Mental Health Policy, Jan 1999Google Scholar

58. Aarons GA, McCabe K, Gearity J, et al: Ethnic variation in the prevalence of substance use disorders in youth sectors of care. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse 2:59-81, 2003Google Scholar

59. Takeuchi DT, Cheung M: Coercive and voluntary referrals: how ethnic minority adults get into mental health treatment. Ethnicity and Health 3:149-158, 1998Google Scholar

60. President's New Freedom Commission on Mental Health: Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America: Final Report. DHHS pub no SMA-03-3832. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003. Available at www.mentalhealthcommission.gov/reports/finalreport/toc.htmlGoogle Scholar

61. Transforming Mental Health Care in America: The Federal Action Agenda, First Steps. Rockville, Md, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2005. Available at www.samhsa.gov/federalactionagenda/nfctoc.aspxGoogle Scholar

62. A Proposed Consensus Set of Indicators for Behavioral Health. Pittsburgh, American College of Mental Health Administrators, 2001Google Scholar

63. Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, et al: Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA 283:2579-2584, 2000Google Scholar

64. Horn IB: Child health disparities: framing a research agenda. Ambulatory Pediatrics 4:269-275, 2004Google Scholar

65. English A, Kapphahn C, Perkins J, et al: Meeting the health care needs of adolescents in managed care: a background paper. Journal of Adolescent Health 22:278-292, 1998Google Scholar

66. Periodic Survey of Fellows: 45 Percent of Fellows Routinely Screen for Alcohol Use. Elk Grove Village, Ill, American Academy of Pediatrics, 2003Google Scholar

67. Rosenbach ML, Garvin NI: Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment and managed care. Annual Review of Public Health 19:507-525, 1998Google Scholar